Dr Watson: Your Guide To The Sherlock Holmes Character

Although John Watson often lacks the quirky brilliance of his friend Sherlock Holmes, he is as indispensable to the Arthur Conan Doyle series as the iconic detective. Depictions of him have varied down the years, but he is considered by many to be loyal, resourceful, and skilled. Without Watson, there could be no Holmes.

Watson's professional life is riddled with trauma. After serving as an army doctor in Britain's war with Afghanistan, he is forced by illness to return to civilian life (via The New Yorker). His financial situation compels him to live with a roommate — and so begins his life with the enigmatic detective. We get some exposure to Watson's skills as a doctor, but they are mostly in the service of furthering his friend's brilliance. We also get few hints of his life outside of his adventures with Holmes — yet Watson does marry, even if his union is a short-lived one.

Few who have read the books or watched the adaptations would deny that the true love of his life is the man he meets through a twist of fate, but who becomes his friend, confidant, and biographical subject. While some adaptations of the stories have painted their union as having a negative angle, one defined by addiction and codependency, few would doubt that Watson is an enriching presence in Holmes' life; and the reverse is certainly true. The sane and dependable Watson embraces excitement and adventure through Holmes, turning down a life of dull Victorian domesticity. He invites us to do the same.

He served in Afghanistan

It's important to remember that Arthur Conan Doyle's writing career took off in the late 19th century, when for better or worse, the UK was gripped by a global expansionist zeal, per Britannica. Much like his literary creation, Doyle was a doctor — and, like John Watson, he served in a war zone, as described by History Today.

We discover in the Sherlock Holmes story "A Study in Scarlet" that Watson spent time in Afghanistan during the Second Anglo-Afghan War, where he worked as an assistant surgeon with the British armed forces. His regiment had been due to go to India, but he was redeployed to Candahar, serving with the 66th Berkshire Regiment of Foot (via the National Library of Scotland) after being loaned out from his main army unit, the Fifth Northumberland Fusiliers.

Watson's experience with the war was miserable and far from glorious. During the battle of Maiwand, he was shot in the shoulder, suffering damage to both his shoulder bone and one of his arteries, and was taken to a hospital in Peshawar (in modern-day Pakistan), where he also went down with a fever. After returning to London, he led a purposeless existence, one where he did little more than fritter away his army pension (as described in the story) and wrestle with what might well be post-traumatic stress disorder. The New Yorker describes how his injury meant he could no longer be on active service, but one thing perks him up — his new friend, Sherlock Holmes.

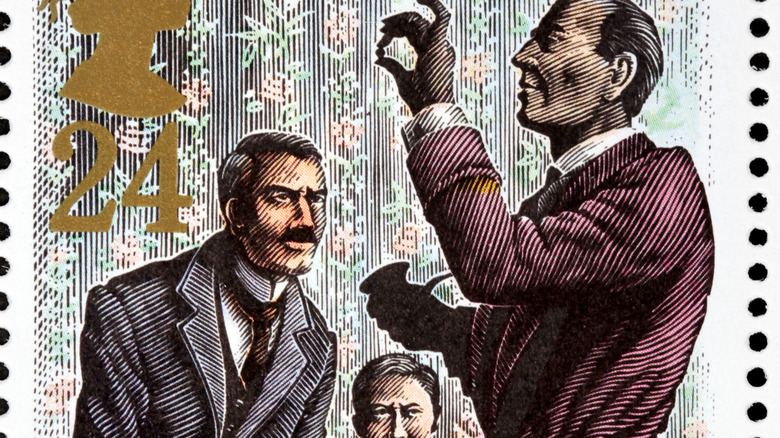

He is the first to record and publish Holmes' work

After watching his new roommate Sherlock Holmes in action, John Watson discovers that Scotland Yard has taken the credit for solving a case, rather than the deserving Holmes. During "A Study in Scarlet," Watson praises his friend's powers of perception, but is disappointed to read in the papers that police officers Lestrade and Gregson have been named as the ones who brought the case to a close. It involved a revenge killing of two American Mormons, who had murdered a young woman they had been potential suitors to, as well as her father.

The man who assisted them is mentioned in Watson's paper as being an amateur with some problem-solving nous, but as little more than a person with great potential to assist and learn from the police. The irony is not lost on the reader, and is certainly not lost on Watson.

Holmes, seemingly content to revel privately in his own brilliance, is indifferent. Yet, in a seminal and shrewd moment, he gives Watson his blessing to broadcast his genius far and wide. Watson insists on recording every case they work on together, ensuring that everyone will soon know the name "Sherlock Holmes." He not only cements a great friendship and iconic crime-solving partnership, but exposes the seedy underbelly of what modern eyes often assume was an age of primness and propriety. As Holmes himself explains, the title is a metaphor for the blood-red vein of violence that permeates the ordinariness of human existence — and their job is to expose it.

His brother is an alcoholic

One of the few hints readers get about John Watson's personal life are to do with his troubled brother. In "The Sign of Four," Sherlock Holmes discerns that Watson has a brother with the initials "H.W." from one of Watson's pocket watches, guessing that the "W" stands for Watson. The date on the timepiece from 50 years ago implies it once belonged to his father, who gave it to John's brother, as watches tend to get passed on to the elder son.

Holmes continues with his examination, observing that the watch is in a bad way, covered in scratches. He suggests that the man who owned it was careless, fumbling around in his pocket with keys and coins and leaving it in a place where it could easily be damaged. As Watson's father had been dead for some time, Holmes gauges that his brother was the person who had left it in this state.

Yet the Watsons did not grow up in squalor. The quality of the watch means that Holmes discerns John's brother was a man who had inherited considerable wealth, shown by how the watch was worth 50 guineas, but had squandered it. He had enjoyed stints of prosperity, but eventually turned to drink and ultimately died penniless. The marks around the keyhole of the watch are a testament to this, having been subjected to an alcoholic's trembling hand whenever the watch was wound at night. Watson initially assumes Holmes has researched his family without his permission — but when Holmes explains his reasons, his friend is pacified and amazed.

If you or anyone you know needs help with addiction issues, help is available. Visit the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration website or contact SAMHSA's National Helpline at 1-800-662-HELP (4357).

He is a skilled doctor

As The New Yorker highlights, some later interpretations of John Watson paint him as farcical, snobbish, and pompous, mostly due to his track record of serving the empire and his seeming disdain for those who don't — a feeling he directs towards himself as much as anyone else (as shown in "A Study in Scarlet").

Yet this skates over his learnedness, attention to detail, and skills as a doctor and surgeon. The journal Medical Humanities explains that although Sherlock Holmes is brilliant, he operates in short bursts punctuated by bouts of idleness and indecision. By comparison, Watson is reliable, consistent, and willing to draw on accepted systems of knowledge — something that makes him a down-to-earth counterweight to Holmes' eccentricities, even if he sometimes lacks dynamism, a criticism Arthur Conan Doyle may have felt applied to the whole of the medical profession.

Nonetheless, Sherlock Holmes places great value on his friend's excellence at his trade. This is shown in a moment when Holmes pretends to have an affliction and does enough research to fool Watson, helping to blindside a suspect in the process. In "The Adventure of the Dying Detective," Holmes convinces his friend he has a highly-contagious tropical disease, knowing that Watson's considerable medical knowledge means if he gets too close, he will see that the illness is a ruse. Despite claiming that Watson's skills are only rudimentary, in the end he confesses that he kept his friend in the dark — due to the great respect he has for his abilities.

He solves cases alone

Self-awareness is a major facet of John Watson's character, to the point where he acknowledges his role is sometimes to display his problem-solving limitations, with Holmes' resulting irritation stimulating his own sharp wit. He seems content to play this subservient role, finding satisfaction in being the tool Holmes uses to sharpen his intellect and a conduit for his genius (via "The Adventure of the Creeping Man").

However, there are times when he joins the dots independently of Holmes, using methods learned from his friend, even though he doesn't always have Holmes' excellent level of insight. He is the main case-buster in "The Hound of the Baskervilles," realizing that movements from a lit candle are signals being sent out by Barrymore to his brother Selden, an escaped convict hiding in the woods, as a way to tell him that food has been laid out to keep him alive. Holmes is magnanimous enough to praise Watson for his insight.

In other cases, he has limited success. In "The Adventure of the Red Circle," Watson is the one who realizes that a strange guest in a boarding house has printed, rather than written out, some documents so that their handwriting cannot be traced. He also learns from Holmes, noting down characteristics about another character, such as his untidiness, labored breathing, and a cluster of legal documents, after Holmes has stated the man is a single lawyer who has asthma (via "The Adventure of the Norwood Builder"). Every so often, Watson's own brilliance is allowed to shine through.

He disapproves of Holmes' drug use

A notorious facet to Sherlock Holmes' character is his habitual drug use. To modern audiences, the references come across as slightly comic; in "The Sign of Four," Holmes agrees to analyze John Watson's pocket watch as a way to prevent himself from taking more cocaine.

However, his friend Watson rarely sees the funny side. Holmes' intravenous cocaine use was probably modest by Victorian standards, as related by the Independent, but Watson admonishes him, pointing out it is bad for his health and could diminish his talent. In "A Study in Scarlet," he describes how the drug would leave him catatonic, lying on the sofa for days on end, while in "The Sign of Four," Watson warns Holmes that the price of the drug's stimulating effect on his mind is damage to his brain tissue.

Dr. Andrzej Diniejko (via The Victorian Web) highlights how cocaine use was so widespread in the late 19th century that it was even recommended to cure a range of medical ailments. As a doctor, Arthur Conan Doyle would have been very aware of the drug's benefits and drawbacks. Lester Grinspoon and James B. Balakar (quoted by Diniejko) also posit that Holmes may well have been addicted to opium and was using cocaine as a way to withdraw. They state that later on in his life, Holmes' only major addiction was to smoking tobacco. "The Adventure of the Missing Three Quarter" details how Watson is the one who persuades him to stop taking drugs, but he is aware that the risk of addiction is always there.

If you or anyone you know needs help with addiction issues, help is available. Visit the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration website or contact SAMHSA's National Helpline at 1-800-662-HELP (4357).

His influence on literature is huge

John Watson came to epitomize the archetype of the "idiot friend," one which became common across literature and film, including in Agatha Christie's "Hercule Poirot" stories. It didn't imply stupidity, but acted as a device to explain aspects of the case to the reader. As described by The British Library, Arthur Conan Doyle introduced three major concepts to detective fiction: the "idiot friend," the "Napoleon of crime" (a criminal too clever for members of law enforcement), and the use of "forensic science" as a way to solve complex investigations.

The "idiot friend" is a useful aid as he needs to have every facet of the case spelled out to him, a way of making sure that the ignorant reader stays informed too. This idea became such an essential device in detective fiction that it inspired characters like writer Agatha Christie's Major Hastings in the Hercule Poirot stories.

In "Adventure, Mystery, and Romance," John G Cawelti argues that another benefit of using this device is that the reader only follows the less-incredible sidekick's perspective — and so can chase incorrect clues or theories, preventing the case from being solved too soon. Sherlock Holmes needs to be following the right clues from the very beginning, so narrating the story from his perspective would have forced Conan Doyle to unconvincingly hide any big twists. Keeping Watson (and the reader) in the dark heightens the sense of drama — and the tension when the "big reveal" happens at the end.

He might have had two wives

John Watson is occasionally shown to have a life outside of his friendship with Sherlock Holmes. He marries Mary Morstan, a governess, but as The Atlantic points out, her death is such a minor detail in "The Adventure of the Empty House" that we are not told how it occurred, and her name isn't even mentioned. Holmes' compassion towards his friend, we are led to believe, is limited, and Watson can only infer sympathy from his friend's behavior, rather than any words of comfort he might have given.

Arthur Conan Doyle had not planned to get rid of Mary in this way, having notoriously tried to kill off Holmes, but failed after a backlash from the detective's devoted fans. When he reunited Holmes and Watson, he likely saw their insular union as only sustainable if Watson had few distractions.

The detached and misanthropic Holmes initially likes Mary, seeing her as charming and amenable (via The Atlantic), but his tolerance for women is short-lived. When Watson becomes a widower, it is implied that he later marries again, although few details are given. Sherlock mentions in "The Adventure of the Blanched Soldier" (one of the few stories told from his perspective) that Watson has abandoned him for his latest bride, and sees the act as a self-absorbed one. It shows how ultimately, there can never be anyone competing with, or intruding on, his rapport with Watson.

He may have a gambling problem

A number of Conan Doyle's stories strongly imply that John Watson has frittered away a good chunk of his army pension on betting, and that his checkbook needed to be kept in a locked drawer by Holmes for his own good. The Irish Times reports that although Watson gained a reputation for being straightforward and sensible, the more human counterpart to Holmes' almost superhuman abilities, he has a more reckless side to his character. In "The Adventure of Shoscombe Old Place," Watson admits, when asked by Holmes if he knows much about horses, that around half of his army pension has been frittered away betting on horse racing.

In another story, "The Adventure of the Dancing Men," the possibility of an investment in South Africa is dangled before Watson, but he is informed by Holmes that his checkbook is under strict lock and key, making the chances of Watson accessing it remote. In fact, his friend even comments that he has not asked to have the key back.

As The Irish Times describes, it appears that Watson is not only aware that he has a gambling problem, but has also taken steps to remedy it. Although Holmes has his own addiction issues, Watson trusts his friend to save him from himself.

Watson and Holmes might be an item

While the idea that Conan Doyle placed a gay sexual subtext is disputed, it is often accepted that a non-platonic, deeply intimate element of Watson and Holmes' relationship exists — the extent to which has been argued over by fans and critics alike.

The Slate podcast (at 11:39) analyzes how, as far back as 1941, gay subtexts have been placed upon the original stories by Arthur Conan Doyle. The essay "Watson was a Woman" by Rex Stout, (via The Nero Wolfe Literary Society), posited from close scrutiny of the texts that Watson was actually Holmes' "wife," while the film "The Private Life of Sherlock Holmes," created by Hollywood legend Billy Wilder, hinted very heavily (via the London Review of Books) at Holmes being homosexual.

Mark Gatiss and Stephen Moffat, the creators of the more recent TV series "Sherlock," acknowledged the rumors by having Mrs. Hudson, Holmes' long-suffering landlord, ask in the first episode if the two would be sharing a bed. They didn't, and both Gatiss and Moffat confirmed that there would be no point in the series where Holmes and Watson got together. This was indeed how the series panned out, despite multiple fan theories and predictions that suggested Holmes and Watson would become a couple – a practice known as "shipping."

The author based Watson on himself

Arthur Conan Doyle studied medicine at the University of Edinburgh and worked extensively as a novice doctor under the tutelage of Dr. Joseph Bell, a physician with an incredible capacity for problem-solving. According to The New Atlantis, Conan Doyle wrote in his memoir "Memories and Adventures" that Bell took a particular liking to him, choosing Conan Doyle to organize his outpatient appointments and to show people into the consulting rooms, while taking notes about their ailments. His pupil noticed that Bell could discover things about the people he examined by a few quick looks, far more accurately than by studying their patient histories.

His powers of deduction inspired Holmes, with Conan Doyle's relationship with Bell — one of observation and absorption — in turn inspiring the iconic John Watson. Conan Doyle's note to his old friend and mentor in 1892, saying that he owed the creation of the legendary detective to him, confirms it without a doubt, per The New Atlantis.

An article in the journal Medical Humanities claims the detective stories can even be read as a critique of the medical establishment: They imply that Watson and the police force are hidebound and uncreative, too beholden to procedure and received wisdom to be capable of the originality Holmes — and his inspiration Bell — display to great effect. Bell in turn claimed in The Strand Magazine that Conan Doyle's good memories of him led him to exaggerate what were simply basic techniques, taught by all good medical professors to their students. Regardless, through Conan Doyle, Bell made an icon — and an unforgettable sidekick in the process.