The Unabomber Hoax That Almost Shut Down LAX In 1995

On June 28, 1995, a letter created turmoil at the fourth busiest airport in the world (via the Los Angeles Times). Previous mail from the same source had proved deadly. The letter received by The San Francisco Chronicle contained a threatening message that read (via The Buffalo News), "WARNING. The terrorist group FC, called Unabomber by the FBI, is planning to blow up an airliner out of Los Angeles International Airport sometime during the next six days."

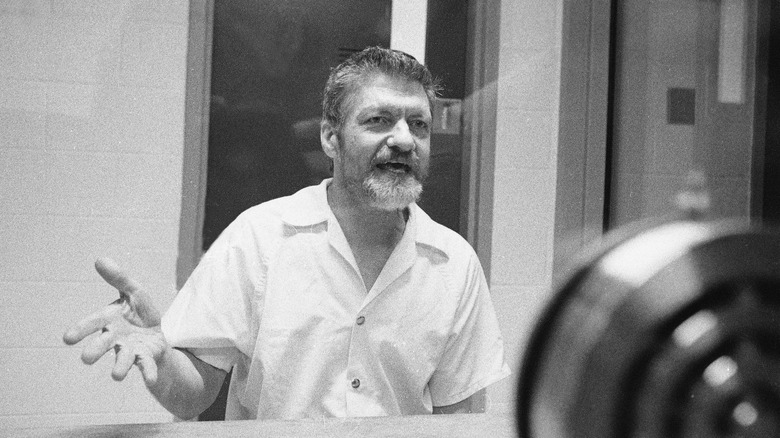

His warning yielded a massive response and major disruption of airline services at Los Angeles International Airport or LAX. The extraordinary security measures were soon employed across the region's airports from San Diego to San Francisco (via "Lone-Actor Terrorism: An Integrated Framework"). Law enforcement was right to respond in force. The unhinged activist had been sending deadly packages across the country since 1978 (via FBI).

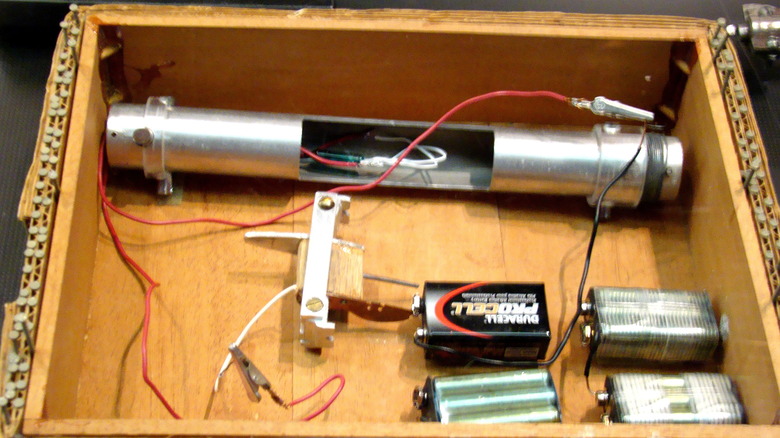

The last delivery sent by the Unabomber in April 1995 proved fatal. A Sacramento timber industry lobbyist, Gilbert Murray, received a homemade bomb that took his life in an acrid cloud of chemicals (via "Unabomber: A Desire to Kill"). In this new threat, the FBI saw a transition from single-individual attacks to mass casualty events. It wasn't since 1979's American Airlines Flight 444 that a terrorist had bombed a plane. The country wondered: Would this be a return of an old airline danger? Another thing stood out in this letter — it was the first time the bomber had offered forewarning.

Mixed messages in the mail

Authorities were thrown when a second letter was received by The New York Times later the same day (via "Lone-Actor Terrorism: An Integrated Framework"). Laboratory testing on both letters confirmed their shared origin and authenticity (via The Washington Post). Yet, the new correspondence confessed that the San Francisco Chronicle's letter was a trick.

The bomber oddly called the threatening message "one last prank." The hoax-confirming second letter expressed an odd mix of sentiments. At first, it read as tongue-in-cheek. The bomber explained (per The Washington Post), "Since the public has a short memory, we decided to play one last prank to remind them who we are. But, no, we haven't tried to plant a bomb on an airline," followed by an ominous single word, "(recently)."

But while admitting the recent scare was meant as a cruel reminder of his influence and power, the second letter also contained a sentiment missing from previous messages: remorse. "In one case we attempted unsuccessfully to blow up an airliner" the letter read, referring to the 1979 American Airlines altitude-triggered bomb (via The Buffalo News). "The idea was to kill a lot of business people who we assumed would constitute the majority of the passengers. But of course some of the passengers likely would have been innocent people — maybe kids, or some working stiff going to see his sick grandmother. We're glad now that that attempt failed." The juxtaposition between threat and sincerity left law enforcement puzzled.

Slow down at california airports

But even after the letter indicating it was all a hoax, precautions at the Los Angeles International Airport remained in place, jamming summer holiday travel (via the Los Angeles Times). One city official remarked, "The FBI is not ready at all to call this thing off." The FBI and other government agencies — including the Secret Service, the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco and Firearms, the U.S. Postal Inspection Service, and the Los Angeles Airport Police Department — all joined ranks providing extra security at the airport. LA mayor Richard Riordan reassured the public that "everything that can be done is being done to maintain the security of LAX."

The heightened security measures were considered extreme by 1990s American travelers. Curbside baggage check-in was now required (via The Buffalo News). Long lines emanated from each gate, snaking around the airport. Passengers were surprised to discover ticket agents asking for photo identification before boarding was allowed (via The Washington Post). U.S. mail service was also disrupted. The flow of 200,000 packages through LAX became a trickle as no parcel weighing 11 ounces or more was allowed on any plane (via the Los Angeles Times). Yet, the steady stream of 2,000 flights a day continued.

Unknown psychology behind the hoax

But why the hoax? Perhaps Ted Kaczynski was feeling ignored. The mass murder of 168 victims in the ground-shaking explosion of Oklahoma City occurred on April 19 of the same year (via FBI). It could be that Kaczynski was feeling overshadowed by the larger explosion that stole the headlines from his April attack. One federal official was quoted by The Washington Post as saying that "the Oklahoma bombing seemed to tweak him. It was almost like, 'Hey, guys. Oklahoma City may have been the biggest bomb, but I'm still here and you can't catch me'." The hoax could have been a cry for more media attention.

Kaczynski correctly predicted the effect of his first letter. He likely derived a feeling of power when it caused security at California airports to scurry and hold up all airmail destined out of the state. Per The Washington Post, the federal official postulated that the threat being so close to the July 4 traveling rush was no coincidence, and the bomber "seems to be saying, 'Look at the power I wield.'" And ultimately, Kaczynski used this attention and power to request something he'd always wanted.

Hoax precipitates unabomber's apprehension

Less than two months after the LAX bomb hoax, Ted Kaczynski parlayed the wave of media attention to make a demand — he requested major U.S. newspapers publish his manifesto. U.S. Attorney General Janet Reno and FBI Director Louis Freeh encouraged the papers to publish the essay (via "Lone-Actor Terrorism: An Integrated Framework"). Eventually, on September 19, 1995, The New York Times and The Washington Post published his 35,000-word manifesto entitled "Industrial Society and Its Future." This brought the Unabomber worldwide attention but also led to his apprehension.

Kaczynski's brother David recognized a common phrase used by both his mother and brother, buried in the anti-industrial manuscript. Within the anti-technology sentiments was a telling idiom only used by David's mother and brother Theodore. It read "you can't eat your cake and have it too" instead of the more common "you can't have your cake and eat it too." David turned his brother in, and this simple transposition caused the end of the Unabomber's terrorism.