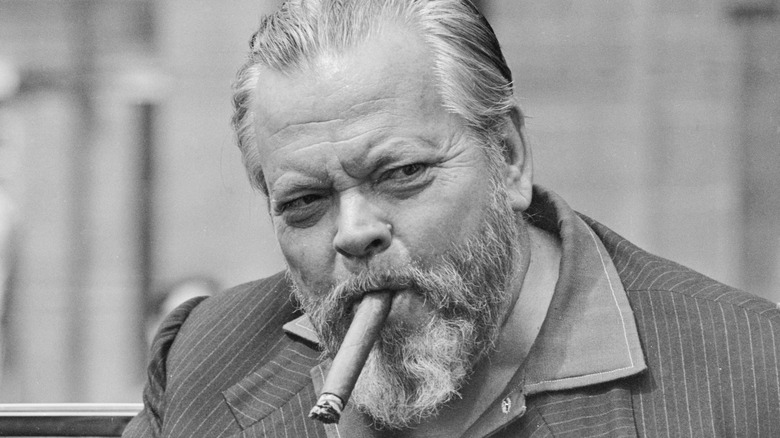

Orson Welles' Final Interview Had A Shocking Conclusion

Merv Griffin, the media mogul who had a long-running talk show, "The Merv Griffin Show," that spanned two decades, never saw his guests before interviewing them. "It would rattle them and it would rattle me," he told Rosie O'Donnell in 1997 (on YouTube). "And it was more fun because it was spontaneous." But as Griffin exited his office on October 10, 1985, he found the famed filmmaker and actor Orson Welles standing there. "Merv, you know I've never allowed anyone to talk about my past. Always the future," he told Griffin."Tonight I feel like talking. Ask me anything you want."

Griffin was shocked. He'd interviewed Welles many times before during nearly 50 guest appearances on his show in nine years, and the two had become friends. And while he considered the filmmaker the most interesting person he'd ever gotten to interview, Welles had always insisted on keeping his past to himself, according to the book "Merv: Making the Good Life Last."

Orson Welles talks of his early successes

Orson Welles stayed true to his word. Merv Griffin had slotted the entire episode, shot before a studio audience at the TAV Celebrity Theater in Hollywood, for their interview. Welles began, as he often did on talk shows, with a magic trick. They then sat down to discuss Welles' life.

George Orson Welles was born on May 6, 1915, in Kenosha, Wisconsin. Both his parents had died by the time he turned 13 and by 16 he had become a successful actor in Dublin, Ireland, per Biography. By his early 20s, he was in Manhattan and had a successful radio show, "The Mercury Theatre on the Air."

"All that success at that age, hard to handle or easy to handle?" Griffin asked Welles (via "The Merv Griffin Show," posted at Tubi). "Anybody that has trouble being successful doesn't have any sympathy from me," he answered with a rueful smile. "I was a success at 16. I was an old-timer by then ... I had a tremendous streak of luck. I was very grateful for that." They did not touch on one of Welles' most famous, or infamous, radio broadcasts, his adaptation of H. G. Wells' novel "The War of the Worlds," which aired on October 30, 1938. The simulated news bulletin frightened a few listeners who believed aliens had indeed landed in New Jersey, per Slate.

Regrets, loves, and Roosevelt

During the wide-ranging interview, Griffin (above) asked Welles about his regrets, loves, and friendship with President Franklin D. Roosevelt. "The regrets. The times you didn't behave as well as you ought to have," Welles said. "That's the real pain." Of his former wife, the Hollywood film star Rita Hayworth, Welles said that she was "one of the dearest and sweetest women that has ever lived. I was lucky enough to be with her longer than any of the other men in her life. She was a wonderful wife."

Welles said the screen siren Marlene Dietrich, whom he'd dated, was "the most loyal friend that anybody could ever ask for. Her loyalty is ferocious." Welles was a good friend of Roosevelt, but Eleanor, the president's wife, was less fond of him. "I made some slighting remark about the cuisine at the White House," he recalled. "But I don't think that's why she didn't like me. She didn't trust me. I had a tendency when I visited to keep the president up too late. I came under the heading of a bad influence." They also discussed Welles' film career, including his masterpiece, "Citizen Kane," which Welles said, "was a great piece of luck because people liked it." The film was a thinly veiled portrait of the publishing tycoon William Randolph Hearst, and Welles admitted Hearst had "hurt my career." He then went on with a devilish grin, "I didn't do him any good either."

A stunning end

At one point in the interview, when Griffin and Welles were discussing Welles having turned 70 that year, Griffin asked him: "But you feel wonderful, don't you?" "Oh sure," he answered and rolled his eyes. What Griffin didn't know at the time was that Welles, who was severely overweight, had cardiac issues, diabetes, and had been in a lot of pain the day of the interview, per "Orson Welles" by Barbara Leaming and the Los Angeles Times. Leaming, who had written an unauthorized biography of Welles and later became a great friend, also appeared on the show that evening.

Afterward, Welles and Leaming left together to go get dinner. A few hours later, Welles died of sudden cardiac arrest in a home in Los Angeles. His driver found his lifeless body in the bedroom the next morning, per the Los Angeles Times. Merv Griffin would later look back on that final interview with his friend and watch it many times. "I honestly believe when I asked him how he felt and Orson rolled his eyes skyward, God chose that moment to say, 'Time to come home'," Griffin recounted in "Making the Good Life Last."