The Grim Life Of Jack Kevorkian, 'Dr. Death'

Death is Nature's redheaded stepchild. People beat, cheat, and avoid Death and then brag about it to their breathing buddies. Death, meanwhile, is mostly friendless, thanks to its thankless job. It's a sad sack of bones in a ragged robe and only gets invited to funerals. Even Death's grin makes people grimace. Not everyone hates the harvester of souls, though. Blue Oyster Cult encouraged people not to fear the Reaper. Fungi think Death's a fun guy. And Dr. Jack Kevorkian became one of Death's deftest defenders.

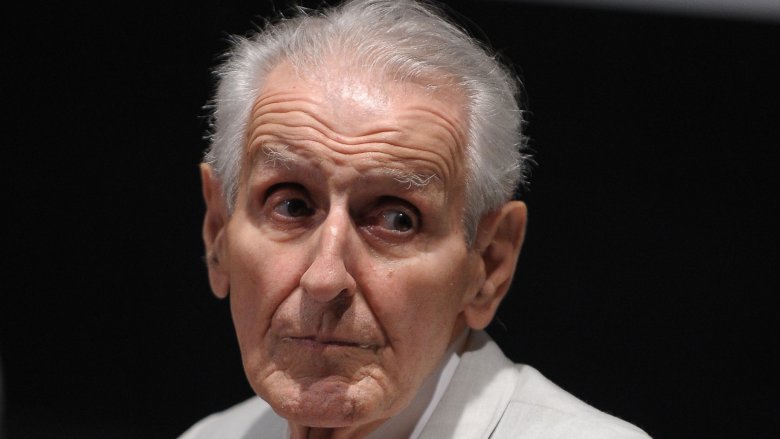

A pathologist driven by pathos, Kevorkian believed a carefully carried-out death could spare the incurably ill from a life of agony. His willingness to act on his convictions got him convicted in courts of law and public opinion. Branded "Jack the Dripper" and "Dr. Death," he rose to prominence during the 1990s. By the time Al Pacino portrayed him in 2010's You Don't Know Jack, everyone knew Jack.

Kevorkian caused disgust and discussion. Detractors deemed him a villainous killer. Supporters hailed him as a hero on a mission of mercy killing. His controversial crusade forced society to ponder whether patients should have a right to die and, perhaps more importantly, whether it's right to help them die.

'Til death do us start

Jack Kevorkian was a walking contradiction, a doctor who prescribed death instead of preventing it. His cadaverous face conveyed the graveness of his undertakings, but his smile seemed genuinely gentle. He looked like a guy who would give you a good morning hug before going to sleep in a coffin. Death proved so central to his life that you'd almost guess he grew up in a graveyard. In a way, he did. Bloodshed brought Kevorkian's parents together, and he would inherit their horrid memories.

As Biography described, Levon and Satenig Kevorkian were Armenian Turks turned refugees. In 1912 they left Turkey to escape the massacres which prefigured the 1915 Armenian Genocide. Levon migrated through missionaries while Satenig dodged a death march. Both ended up in Michigan, where they first met. Their meeting blossomed into a marriage. After some potent pollination they fruitfully multiplied.

In 1928 the Kevorkians produced their second of three children, Murad. Americans rechristened him Jack. Raised during the Great Depression, Jack watched his parents toil tirelessly to ensure his childhood wasn't depressing. Depressing thoughts consumed his young mind, however. Per the University of Michigan, his mother told him of the holocaustic horrors she witnessed in Turkey.

Kevorkian grew up in a deeply Christian home, but couldn't reconcile why a supposedly omnipotent, loving god would allow the Armenian Genocide. No one could give a satisfactory answer, and he grew dissatisfied with church. It wasn't the last institution to disappoint him.

A matter of life from death

Kevorkian didn't just doubt divinity as a kid; he doubted everything. According to Biography, he challenged authority figures and ideas with incisive insights. His intellectual restlessness led him down the path of pathology. After ping-ponging between unstimulating majors at the University of Michigan he settled on medicine. He graduated in 1952 and focused on pathology.

Before long, Nature's dreaded stepchild reared his dead red head again. The Korean War broke out and Kevorkian served as a military medic. Reuters reported that during that period he pondered whether blood from fresh corpses could sustain living soldiers. The idea smacked of inverted vampirism, life drinking in lifelessness. After some laboratorial tinkering, he sought research funding from the Pentagon but got shot down like a falling syringe.

Kevorkian foolhardily forged forward, even subjecting himself to a corpse transfusion. He contracted Hepatitis C as a result. While the doctor fought to save soldiers, his mother battled cancer. According authors Neal Nicol (a colleague of Kevorkian) and Harry Wylie, upon hearing about his mother's hellish health, the skeptical intellectual "refused to believe it."

Refusal proved futile. An abominable abdominal cancer ravaged Satenig Kevorkian from belly to bone. Her son berated hospital staff for failing to cure or comfort her. She endured perpetual pain, and he urged doctors to dose her with copious opiates. The physicians refused, fearing the dying woman would become comatose or drug-addicted. Kevorkian "watched his mother die in pain, helpless to do anything to help her."

Do know harm

Jack Kevorkian saw an oncological monster murder his mother. Despite being a doctor himself, he couldn't persuade practitioners to ease her misery with meds. It's impossible to quantify the mental toll that must have taken. But in 1993, journalist Jack Lessenberry tried anyway, asking Kevorkian if his mother's dire fate affected his views on physician-assisted suicide. The doctor didn't know, but he knew his morbid deeds weren't simply a trip down Traumatic Memory Lane.

Kevorkian's support for euthanasia predated his mother's cancer battle. In his words, "I already knew it was right. From the time I first saw horribly suffering patients in the hospital where I was being trained as a young doctor, I was absolutely convinced that this was right."

As he recalled, an immobile man moved him in that direction: "What finally happened was there was this fellow in Michigan, David Rivlin, who was a quadriplegic, on a respirator, and he went on television and said he wanted to die. I went to see him and realized that I should invent something to help him."

For many people "help" and "die" are practically antonymous terms. But for Kevorkian, death was always a means to a greater end. With respect to assisted suicide, it was a way to respect patients' autonomy. He also believed death could advance scientific knowledge. In 1958, he advocated recruiting death row inmates for pain-free but lethal medical experiments. According to Biography, off-put colleagues dubbed him "Dr. Death."

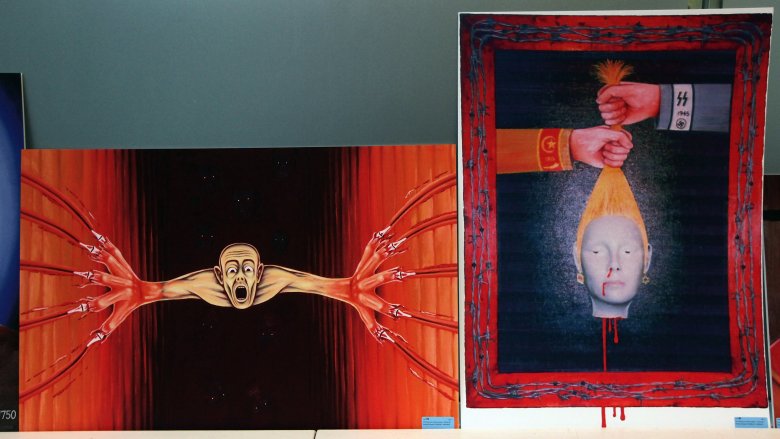

Art imitates lifelessness

In his interview with Jack Lessenberry, Kevorkian argued he was "obsessed with life." Yet while in med school, he obsessively photographed the eyes of dying patients. He claimed it could help doctors distinguish between comas and dirt naps. But the 1993 book Appointment with Doctor Death (via PBS) revealed his "number one reason was because it was interesting" and his "second reason was because it was a taboo subject." He clearly had an eye for the macabre and a penchant for pushing the envelope. Those sound like ideal traits for an artist or a thrill killer. Kevorkian happened to be the former (and the latter, depending on whom you ask).

Per Atlas Obscura, during the 1960s Kevorkian enrolled in an oil painting class. Kevorkian's first work, "A Very Still Life," depicted a skull with an iris flower growing through its eyehole. It was a visceral visual pun and arguably autobiographical. In that painting, life literally stemmed from death, a recurring theme for Kevorkian. In med school, he examined dying eyes for signs of life. His parents met after escaping a massacre. His corpse transfusions research banked on bloodshed yielding lifeblood.

Much of Kevorkian's artwork (some of which is shown above) touched on things that touched him personally: medicine, massacre, music, piety, and his parents. His creative vision was accompanied by a musical ear. In 1997, he produced a jazz album, which, like his first painting, was titled A Very Still Life. It was another Kevorkian contradiction. Throughout his life, he was anything but still.

I am become Dr. Death

During the late 1970s, Kevorkian's flirtation with art became a full-fledged affair. The University of Michigan explained that his marriage to medicine had been marred by bickering over his controversial views. Per PBS, he quit a job as chief pathologist at a Detroit hospital and headed to California to make a movie. He poured his heart, soul, and life savings into making a film about Handel's "Messiah." The film lacked a distributor and would tank like a military aquarium. Kevorkian found himself living in a car by 1982, per Atlas Obscura.

After the failure of his messiah film, Kevorkian resurrected his deathly medical pursuits. He journeyed to the Netherlands to learn the art of assisted suicide. This rekindled his inflammatory habit of publishing articles that advocated euthanasia. But in his case, the pen proved slighter than the sword. The doctor resolved to practice what he preached.

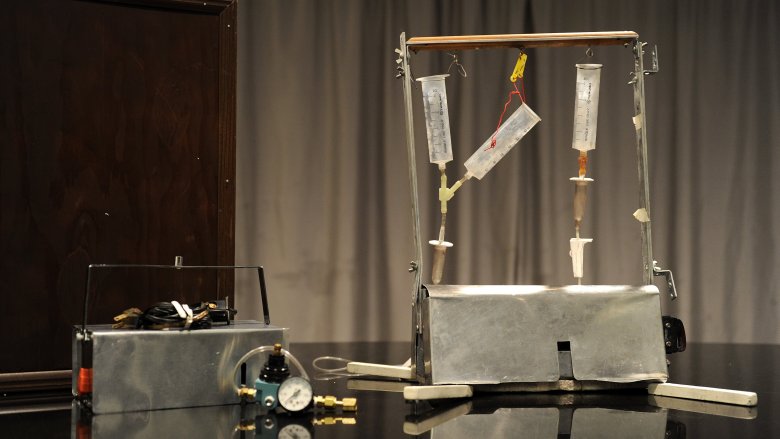

In 1989, Kevorkian built a suicide machine which he christened the Thanatron ("instrument of death" in Greek). The following year, he used the device to help Alzheimer's patient Janet Adkins end her life. It marked the first of many suicides supervised by Dr. Death. Patients impatiently flocked to him, desperate to unshackle themselves from illness. The doctor diligently obliged. Although he had mishandled Handel's "Messiah," he would find his calling as a self-anointed savior for the sick.

Do now go gentle into that good night

When poet Dylan Thomas watched his ailing father wilt away, he reacted by writing "Do not go gentle into that good night," wherein he urged his dad to "rage, rage against the dying of the light." To Jack Kevorkian's ailing patients, death was the light at the end of a torturous tunnel. They refused to rage against it. Rather, Dr. Death and his suicide machine became all the rage.

The Atlantic explained that a patient's gentle journey into "that good night" began with the push of a button or pull of a handle. The Thanatron (pictured above) was the first of two suicide machines Kevorkian constructed. It consisted of "household tools and spare parts you might find in any suburban garage." These parts pumped saline through an IV until the patient pushed a button to deliver a dose of thiopental. After a 60-second surge of this solution, the patient fell asleep, and inflow of heart-stopping potassium chloride would seal their fate. A relative of one of Kevorkian's patients told The Telegraph it "was the least painful way to die."

Kevorkian stored the Thanatron in the back of a modified Volkswagen van. Alongside it resided his second suicide machine, the "Mercitron," which contained a canister of carbon monoxide attached to a cylinder. That cylinder sent the lethal gas to a mask when a patient pulled a handle. The Mercitron accounted for most of the doctor's deaths. By Kevorkian's count, 130 people employed his machines to bid the world goodnight.

Acquitters never win

While patients faded like light in the night, prosecutors raged against the machines that caused the darkness. Per PBS, the state of Michigan brought murder charges against Kevorkian for facilitating Janet Adkins' suicide in 1990. However, a court acquitted him, and he refused to quit euthanizing people. The following year he oversaw the suicides of a woman struggling with pelvic pain and another suffering with multiple sclerosis.

The Michigan Board of Medicine intervened to end the intravenous deaths by terminating Kevorkian's medical license. Their intervention was in vain. The grim guru continued his campaign unabated, sparking a legal debate. State lawmakers outlawed assisted suicide. Undeterred, the determined doctor continued his mercy killings, and in 1996 he again found himself at the mercy of a gavel. But not even laws could handcuff Kevorkian.

The LA Times reported that Kevorkian circumvented the assisted suicide ban by exploiting a flaw in the law. The ban didn't bar people from administering "medication or [using] procedures that hasten death, as long as the intent was to relieve pain and not to kill." Defense attorney Geoffrey Fieger maintained that Kevorkian's main intent was to end suffering, not lives. The argument proved persuasive.

Kevorkian bested the ban and a growing base of fans banded together to show their support. According to The Guardian, his courtroom backers wore badges which, appropriately, read "I back Jack." With a movement ignited and authorities incited, there was no turning back for Jack.

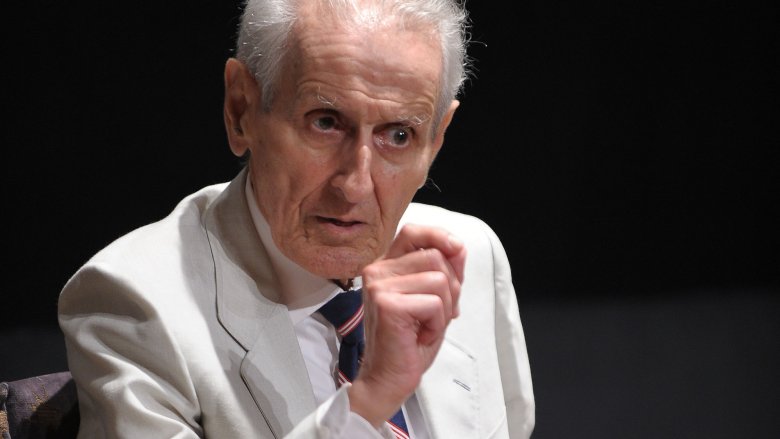

Inalienable rites

The American public gawked and gasped at the ghastliness of Jack Kevorkian's euthanasic exploits. Dr. Death thrived in the limelight. He parried and parodied criticism with blistering jibes and diatribes. As NBC described, he cast his castigators as religious zealots and Nazis and referred to opposing physicians as "hypocritic oafs." Meanwhile, Kevorkian compared himself to Martin Luther King, Jr. and Gandhi.

Dr. Death played the role of a troll who burned bridges and fed off of umbrage. While on trial for assisted suicide in 1996, he appeared in court clad in "a white wig tied with a pink ribbon, blue knee-length britches, a gold brocade coat, buckle shoes and a tricorn hat," per The LA Times. The firebrand brandished a letter purportedly penned by Thomas Jefferson in support of suicide. When asked about the absurdity, Kevorkian shot back: "It's silly to have modern dress when you're dealing with ancient jurisprudence."

His antics had a deeper point than simply needling nemeses. If life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness were uninfringeable rights, then the terminally ill should be free to die if they weren't happy pursuing life. It was equal parts art and artful argument.

Uncompromising to a fault, Kevorkian endangered his own life to help others end theirs. According to The LA Times, in 1993 he went on a grueling hunger strike after an arrest. Like Martin Luther King, Jr., Kevorkian had a dream. Evidently, that dream was to be a Gandhi for goners.

Gone in 60 minutes

Jack Kevorkian donning Colonial garb grabbed attention, but it paled in comparison to the stunt he pulled two years later. On November, 22, 1998, an especially memorable episode of 60 Minutes featured Dr. Death at his doctor-deathliest. He didn't just direct a person's death, he directly caused it. Four days before Thanksgiving, viewers would witness a woe-weary family give thanks for mercy killing.

As The New York Daily News described, the incident actually occurred in September. Thomas Youk wanted lasting relief from Lou Gehrig's disease. The illness had transformed his body into a living tomb. Youk's wife lamented that her husband's limbs no longer functioned, he suffered insufferable agony, and his own saliva posed a lethal choking hazard. In her words, "We were at the end of our rope." Kevorkian ostensibly saw it as an opportunity to rope in the public with a public demonstration of euthanasia.

After obtaining Youk's verbal consent, Kevorkian administered a muscle relaxant followed by a lethal dose of potassium chloride. There was no button to push, no Thanatron to bear the blame. Kevorkian had become the instrument of death. His comportment was as glib as it was glum. Before injecting the toxic tincture, he uttered an "okeydokey." He later Okayed his doings, remarking, "It's not necessarily murder. It could be manslaughter, not murder. But it doesn't bother me what you call it. I know what it is. This could never be a crime in any society which deems itself enlightened."

The jailhouse that Jack built

During the 60 Minutes broadcast, Dr. Death practically begged police to bag him. "They must charge me," he reasoned. "If they do not, that means they don't think it's a crime, because they don't need any more evidence, do they? Do you have to dust for fingerprints on this?" The answer to both questions was unquestionably "no." Kevorkian was clearly the murder weapon, and authorities would be too busy wiping the courtroom floor with him to worry about dusting.

What went down was a straight-up murder in the eyes of law enforcement, and Dr. Death's defense was skeletal at best. Per an article in the British Medical Journal (now the BMJ), Kevorkian claimed that Youk yearned for euthanasia. His primary evidence was a video of the patient in the grips of his crippling condition. However, his obvious unhappiness didn't obviously mean he wanted to die. Youk's widow and brother had approved of the procedure, but that proved nothing.

Judge Jessica Cooper gaveled the final nail in the coffin, opining that Youk's consent didn't matter. The jury judged that Kevorkian executed his patient and found him guilty of second-degree murder. As CNN detailed, Judge Cooper read Kevorkian the riot act: "You had the audacity to go on national television, show the world what you did, and dare the legal system to stop you. Well, sir, consider yourself stopped." Cooper didn't stop there. She then handed down the sentence: 10 to 25 years behind bars.

A very stilled life

Jack Kevorkian's prison stint lasted eight years, according to the New York Times. He earned his freedom in 2007 through good behavior. Though he had orchestrated his own incarceration, Dr. Death described his release as "one of the high points in life." He shared that high with supporters who "lined a road to the prison under gray skies, holding hand-lettered signs, including, 'Jack, Glad You're Back' and 'Jack, We're Glad You're Out of the Box.'"

Puns couldn't undo the punishment, but prison couldn't reform Kevorkian's opinions. He would fight to legalize assisted suicide. Only, next time he would do it legally. Unfortunately, his own time was running out. NBC explained that Hepatitis C, diabetes, and other maladies had hampered his health and contributed to the prison's decision to free him. Illness had issued a far more permanent verdict.

Despite his failing frame, the famously frail Kevorkian clung to life. He ran for Congress and got clobbered. He watched Al Pacino immortalize him on the silver screen. And in 2011 he died listening to his favorite composer, Johan Sebastian Bach. Unlike his patients, he didn't commit suicide or even attempt it. Pneumonia, kidney complications, and a blood clot did him in. It almost seems ironic. But to see incongruity in Dr. Death's death misses his message.

Kevorkian wanted life to be a choice. To deny that choice was an affront to medicine and morality in his mind. His fundamental mission was always to save lives, even when it meant ending them.