The Messed Up Truth About The Cuyahoga River Fires

The Cuyahoga River runs through Cleveland, Ohio, in the Midwestern United States, but despite being a tributary of Lake Erie, the river used to have more in common with a burning building than a body of freshwater. And it wasn't until the 21st century that the river regained its status as a livable ecosystem.

Since the mid-19th century, the Cuyahoga has caught fire at least 13 times. But it was never the river itself that was burning. Instead, it was all of the oil and industrial waste that was being dumped into the river by the factories operating nearby.

For over 100 years, the Cuyahoga River intermittently burst into flames as industrial waste continued to be dumped into the waters. And although its final blaze wasn't the largest, it occurred in the midst of an environmental crisis that led the federal government to install stricter environmental protections and regulations. And although it took almost another half-century for many of the waterways to return to a sense of equilibrium, many more endangered rivers and lakes across the United States still need protection against pollution. This is the messed up truth about the Cuyahoga River fires.

An industrial city

During the 19th century, the city of Cleveland, Ohio, and its surrounding area rapidly industrialized. The Ohio and Erie Canal system, which was opened in 1827, allowed for increased trade, according to the National Park Service. And the Encyclopedia of Cleveland History writes that once railroads were established, the supply of raw materials expanded as Cleveland was connected to both coal fields and iron ore regions.

Soon many different types of companies, ranging from oil refineries to oats mills, set up shop near the Ohio and Erie Canal and the Cuyahoga River. Within 50 years, countless factories were established along the river while houses were crammed in between. As the waterfront became one big industrial zone, it wasn't long before all the industrial waste and sewage from the factories and the people started filling up the Cuyahoga River. In "Where the River Burned," David Stradling and Richard Stradling write that "dredge spoils and urban waste, including garbage, provided the fill that gave the city more flat lakeside land."

By the 1870s, Cleveland was the most important iron-manufacturing center in the country and one of the top oil refining capitals in the United States, thanks in part to the presence of John D. Rockefeller's Standard Oil Co. Meanwhile, agricultural work had quickly been replaced by oil refineries, iron works, and copper smeltings, per "Cleveland: A Metropolitan Reader." The effect was noticeable. In 1881, Cleveland Mayor Rensselaer R. Herrick even described the Cuyahoga River as "an open sewer through the center of the city," per Cleveland Magazine.

A polluted river

It didn't take long for the Cuyahoga River to develop a reputation as a polluted waterway. The National Park Service writes that as early as 1863, the Cuyahoga River was described as having a murky color. Five years later, in 1868, the river caught fire for the first time. Luckily, according to "The Death and Life of the Great Lakes" by Dan Egan, there were no casualties, and the fire didn't do much property damage. Although there were calls for the local government to "rid the river of this nuisance at once," nothing was done. In the 19th century alone, the Cuyahoga River burned two more times: once in 1883 and again in 1887 (per the National Park Service).

It became impossible not to notice the state of the river. According to "Cleveland: A Metropolitan Reader," upon recently immigrating to Cleveland, a man described the Cuyahoga River in 1889 as "yellowish, thick, full of clay, stinking of oil and sewage. The water heaped rotting wood on both banks of the river; everything was dirty and neglected."

However, many tried to spin the rampant pollution of the river and the noxious air pollution as a necessary consequence of being an industrial city. The Cleveland Leader newspaper even reportedly published a piece claiming that Cleveland would be mocked by other cities if they disparaged industrial pollution and "indict[ed] her rolling mills because they smoke, and prohibit[ed] coal oil refineries because they smell badly."

A river of fire

Throughout the first half of the 20th century, the Cuyahoga River burned often, catching fire no less than five times before 1950 (via the National Park Service). And the flames weren't always harmless. Dan Egan writes in "The Death and Life of the Great Lakes" that during a 1912 fire, five boat mechanics lost their lives by being burned alive.

The fire on May 1, 1912, started from an oil leak from a Stanford Oil cargo ship, per Popular Mechanics. According to the journal Environmental History, the leaking oil covered the river and after catching on fire, spread rapidly. The Plain Dealer newspaper later described how "without warning, a shriveling blast of blue flame from the water beneath them wrapped the drydock in fire." At the time, five men had been caulking a boat, and they were unable to escape the roaring flames in time. Several boats, including a yacht, were also destroyed. By this point, the frequent fires taught people to be well aware of the fire hazard posed by the Cuyahoga River. Many who worked on or near the river started to live in fear of "the moment [when] the river is going to blaze up and destroy us."

And these weren't the only river fires to occur in the United States during this time. In 1921, the Hudson River along Manhattan Island in New York State burned when the exhaust of a motorboat ignited some oil on the river. The resulting fire destroyed a warship (per Environmental History).

Over $1 million in damage

Several fires burned across the Cuyahoga River over the following decades, and by the 1950s, the danger still hadn't subsided. Dense oil patches covered the river, at some points so wide that they spanned the whole width of the waterway, which "bubbl[ed] like a beer mash." According to The Allegheny Front, there were even signs all across the river that said "No swimming" and "Use at your own risk." The danger posed by the pollution wasn't a secret, with fire officials openly acknowledging that a fire here could immediately destroy a company, per Environmental History.

According to Popular Mechanics, a river fire that started on November 1, 1952, caused the most property damage out of all the fires that the Cuyahoga River faced. Burning for three days (per Cleveland.com), the fire destroyed the dry docks of the Great Lakes Towing Company, along with several boats. Firefighters managed to contain the fire before it spread to the Standard Oil refinery, but the fire caused almost $1.5 million in damages, according to the National Park Service. Cleveland Magazine writes that, like the 1912 fire, the 1952 fire was also caused by leaks from Standard Oil.

The 1952 river fire garnered some media attention, but rather than reporting on the fact that the Cuyahoga River caught on fire yet again, "The Death and Life of the Great Lakes" author Dan Egan notes that the media attention focused on the destruction of the Great Lakes Towing Company instead.

A small cleanup effort

After the 1952 fire on the Cuyahoga, there was an attempt to remedy the situation. Cleveland Magazine writes that there were local cleanup efforts, and in 1968, the city of Cleveland even approved a ballot measure to allocate $100 million to properly invest in cleaning up the river. But almost 15 years later, the Cuyahoga river was still considered to be one of the most polluted rivers in the United States, according to "Environmental Health in the 21st Century." But safety precautions also increased, as fireboats started being kept by the river after the 1952 fire, according to "Crimes That Changed Our World" by Paul H. Robinson and Sarah M. Robinson.

The pollution in the Cuyahoga was so bad that it got to the point where few lifeforms could even survive in the river ecosystem. In the book "Environmental Law for Biologists," Tristan Kimbrell notes that, by the 1960s, algae was the only living thing that could survive in parts of the river.

According to "The Death and Life of the Great Lakes," the cleanup was largely ineffective because industrial companies continued to dump waste into the river with impunity. Author Dan Egan writes that water pollution laws at the time were "toothless to stop industries and cities from treating rivers as liquid landfills; civil and criminal penalties for polluters were basically nonexistent."

The 1969 fire that changed everything

By 1969, the Cuyahoga River was still in an abysmal state. According to Smithsonian Magazine, there was even an understanding among people that worked or lived near the river that falling into the river meant an immediate trip to the hospital. In addition to the industrial waste and sewage that continued to be poured and leaked into the river, animal carcasses would also be seen in the water. "Everyone knew it was polluted, but pollution meant industry was thriving," the magazine reports.

On the morning of June 22, 1969, as a train passed over the Cuyahoga River, it caused a spark that dropped down onto the oily river and caused yet another fire. This time, the fire was relatively small compared to the blazes that had burned in the past. Cleveland Magazine writes that the fire was put out in less than 30 minutes, and few really considered it to be a big deal. Chief William Barry of the Cleveland Fire Department wasn't even called to the fire (per "Crimes That Changed Our World") and later described it as being "strictly a run of the mill fire," according to the book "Down to Earth" by Ted Steinberg.

The 1969 fire also caused minimal damage compared to the previous blazes, amounting to only about $50,000, according to "Environmental Health in the 21st Century." (Some sources estimate the fire's financial toll at $100,000 or more.)

Years of river fires

The state of rivers in the U.S. Midwest was so bad in the 1960s that the Cuyahoga River fire wasn't the only river fire based in a Lake Erie tributary that blazed in the decade. Popular Mechanics writes that the Buffalo River was the site of a fire on January 24, 1968, and it wasn't the first fire that the river had experienced. Firefighters had put out another fire on the Buffalo River in September 1967, per Western New York Heritage.

And less than five months after the Cuyahoga River burned, the Rouge River in Michigan (pictured above) caught fire on October 9, 1969. Michigan Radio reports that, similar to the Cuyahoga River, the Rouge River suffered from companies dumping their industrial waste into its waters, releasing millions of gallons of waste every year with little to no consequences for the companies. Instead of sparks from a passing train, the fire was caused by sparks from a welding torch.

When the Rouge River caught on fire in October, some of the flames were estimated to have gone as high as 50 feet in the air, according to "Rouge River Revived," edited by John H. Hartig and James L. Graham. Luckily there were no casualties, but it still took 65 firefighters to quell the blaze.

Mayor Carl Stokes pushes for reform

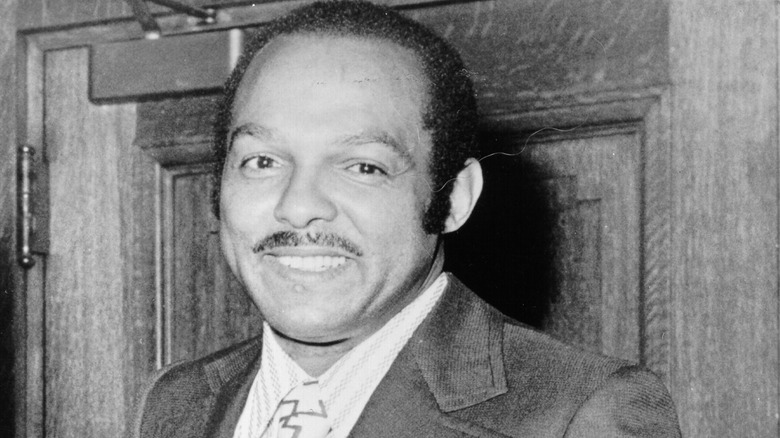

In 1967, Carl Stokes was elected mayor of Cleveland, becoming the first Black mayor of a major U.S. city (via the National Park Service). Stokes pushed for environmental cleanup, and when the Cuyahoga River caught fire on June 22, 1969, he promptly visited the river with reporters the day after the blaze to give them a tour of the scene, according to the National Park Service.

Stokes blamed the state of Ohio for the condition of the river since the state was in charge of regulating water pollution enforcement. Meanwhile, the state claimed that the city's sewers and runoff were responsible for the fire. But according to "The Death and Life of the Great Lakes," when federal environmental regulators came to inspect the river, they concluded that the pollution, and subsequent fire, was caused by all the oil, debris, and chemicals deposited by the companies operating by the river. As soon as the river reached the factories, its water reportedly went from a normal green color to a thick, brown sludge that emitted noxious odors.

Public hearings

At the time, Mayor Carl Stokes' brother, Louis Stokes, was serving in the House of Representatives as a congressman from Ohio. According to "Ecological Restoration in the Midwest," edited by Christian Lenhart and Peter C. Smiley, Jr., both Mayor Stokes and Representative Stokes testified before Congress and spoke of the importance of creating federal regulation regarding pollution and environmental protections.

Meanwhile, Republic Steel, which Cleveland History writes had been operating by and polluting the Cuyahoga River since 1937, refused to participate in the hearings or admit to any responsibility. A spokesman from U.S. Steel, another company operating in the area, also didn't see a problem, claiming that "we are in complete conformity with all existing federal and state codes relating to water quality in the Cuyahoga River," per "The Death and Life of the Great Lakes."

At the end of the day, no one was fined or penalized for turning the Cuyahoga River into a fire hazard.

The Time magazine story

The 1969 Cuyahoga River fire is credited with inspiring the environmental movement, but since it burned for only about 24 minutes, the Cleveland Plain Dealer newspaper didn't manage to get a photograph of it. When Time magazine published an article about the Cuyahoga River fire in its August 1, 1969, issue, Cleveland Magazine reports that the accompanying photograph was actually from a 1952 fire.

But despite the fact that the Time magazine story wasn't even a cover story and didn't feature a real photograph of the 1969 blaze, the story of the Cuyahoga River fire spread across the country. Ideastream Public Media reports that this can possibly be attributed to the fact that the Time magazine issue that included the story about the Cuyahoga River fire was the Chappaquiddick issue, featuring a cover story about Ted Kennedy and the death of Mary Jo Kopechne, one of the Boiler Room Girls.

Because national attention was already on the Kennedy incident, many more people outside of Ohio also found out about the Cuyahoga River fire and about the river that, in Time magazine's words, "oozes rather than flows" (per "Crimes That Changed Our World").

The Clean Water Act

The Cuyahoga River fire wasn't the only environmental pollution disaster to occur in 1969. According to "Environmental Law for Biologists," an oil spill in the Santa Barbara Channel in California and the deaths of 26 million fish from pollutants in Lake Thonotosassa in Florida, both of which occurred in 1969, also became rallying cries for the environmental movement.

Within three years, several environmental protections were established, ranging from newly minted agencies to meaningful regulations, writes Cleveland Magazine. The Environmental Protection Agency was created in 1970, and the Ohio Environmental Protection Agency in 1972. In addition, "Ecological Restoration in the Midwest" reports that the Clean Water Act was also passed in 1972 in an attempt to hold accountable companies that polluted, followed by the Resource Conservation and Recovery Act of 1976 and the Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act of 1980.

"The Death and Life of the Great Lakes" author Dan Egan writes that although the Clean Water Act fell short of cleaning up the waterways of the United States by its target dates of the 1980s, there were noticeable improvements over the years that can be attributed to the act. By 2017, the Cuyahoga River even had up to 60 species of fish swimming in it.

River fires today

Although the United States hasn't had any major river fires in the past 50 years, oil spills and industrial waste in rivers still continue to cause river fires around the world. After an oil pipeline under the Ob River in Siberia, Russia, burst in March 2021, the oil on the frozen river caught fire, leading to a burning hole in the ice that was estimated to be a quarter of an acre large, The New York Times reports. Hindustan Times writes that in February 2020, there was also a large fire on the Burhi Dihing River in Assam, India, that was caused by a leaking underground Oil India Limited pipeline.

Rivers aren't the only waterways falling victim to flames. In 2021, a large fire erupted in the Gulf of Mexico due to a burst pipeline, per Ocean Info. Although the fire was extinguished in just a few hours, ocean life was greatly affected by the fire and all the plankton in the area were likely killed.