Discoveries In Egypt That Changed What We Know

It may be easy to conclude that everything ancient Egypt is seriously old news. We've known for thousands of years about the long-lived civilization that sprang up along the Nile. Even a casual search may make it seem like the last big find happened a century ago, when British archaeologist Howard Carter cracked open the dazzling tomb of King Tut during the early years of the Jazz Age (via The New York Times). So what could possibly be waiting in the picked-over sites of Egypt to surprise us?

Not so fast, dear but impatient readers. Ancient Egypt was a massive and vastly enduring civilization — not counting pre-dynastic periods or later Greek and Roman occupations, it was around in one form or another for about 3,000 years before Alexander the Great strolled in and took over in 332 B.C. (via History). It simply can't be summed up after just a measly couple of centuries of excavating. As many modern archaeologists can tell you, there remains quite a lot to uncover about this society and its people.

Even within the past few years, excavations throughout modern Egypt have revealed stunning new finds that can dramatically alter our perception of this complex time and place. As it turns out, even old-school archaeologists can still be startled by what comes out of the ground there. Here are some recent discoveries that seriously challenged our assumptions and changed what we know about ancient Egypt.

A massive sarcophagus was linked to Ramses the Great

For the dead of ancient Egypt, it wasn't enough to be mummified. A deceased person also had to be laid to rest in style. Ideally, this included a respectable tomb and items meant to make their afterlife easier, like jewelry, food, and shabti dolls intended to spring to life as servants in the hereafter (via World History Encyclopedia). But it also meant that most of the deceased would have wanted an especially nice case: the coffin.

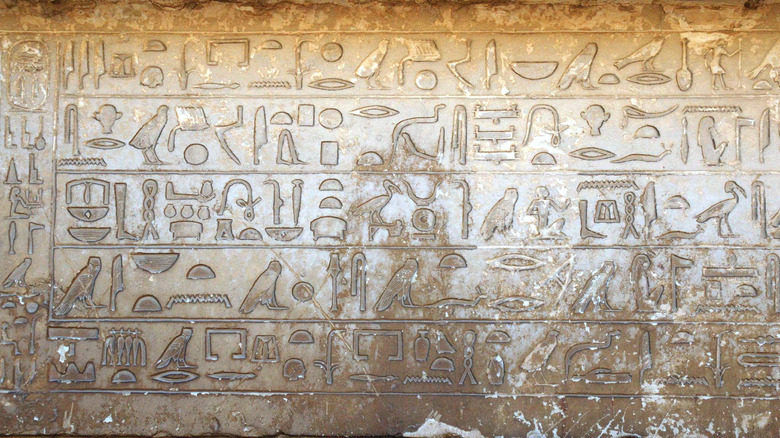

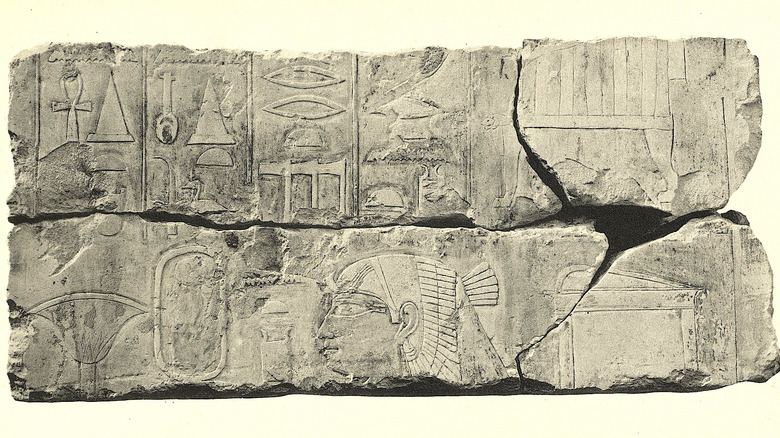

As the American Research Center in Egypt explains, coffins not only helped to preserve a body but also carried vital symbols and magical spells meant to streamline the transition into the afterlife. Eventually, coffins also began to depict the deceased as gods themselves. The bigger the funerary budget, the finer the artwork and the material.

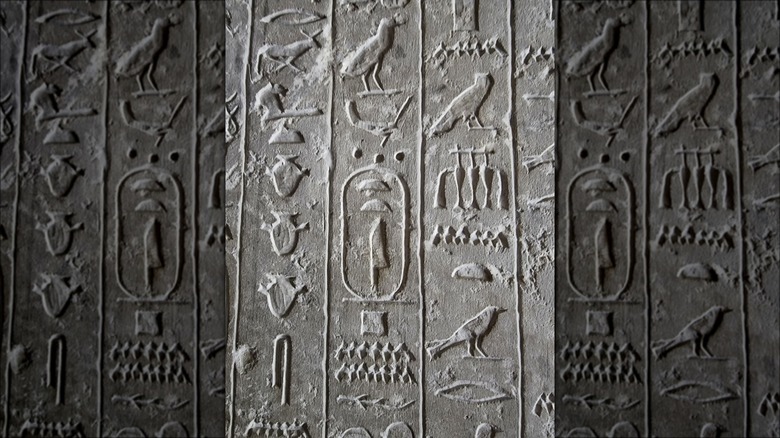

By that reasoning, the gigantic stone sarcophagus uncovered by researchers at Saqqara in late 2020 must have belonged to a pretty high-ranking personage. Of course, excavators could also read the carvings all over the piece, which indicate it was meant for Ptah-em-wia, the treasurer of Ramses II, per The Guardian. Even more dramatically, the huge artifact was found at the bottom of a shaft nearly 30 feet deep and was discovered by Egyptologist and professor Ola El Aguizy. Not only was El Aguizy's find of a sarcophagus in its original spot exceptionally unusual, but it could reveal more about the inner workings of the court of Ramses the Great.

An entire lost city was found in the desert

It seems strange to think of an entire city disappearing, especially for a society that adhered to the use of historical documentation. As the BBC reports, there had been records of the city of Aten, constructed during the reign of pharaoh Amenhotep III, in the 14th century B.C. But it had seemingly vanished into the desert near modern-day Luxor. In an April 2021 statement announcing the rediscovery of Aten, Egyptologist and former antiquities official Dr. Zahi Hawass noted that numerous foreign groups had tried and failed to find the settlement. But it was an Egyptian team that finally traced it, during an attempt to uncover the mortuary temple of the pharaoh Tutankhamun.

Aten wasn't just some backwater, either. According to Hawass, the sprawling settlement was a major center that arose during the most prosperous era of the kingdom. Among the finds was what appears to have been an industrial-level kitchen that produced food for a large number of workers. Another residential area sported a unique zigzag-shaped wall and a production facility for mud bricks, which bore the mark of Amenhotep III. There are even tantalizing hints of the transition from the entrenched worship of many gods to the monotheistic worship of the sun disk established by Amenhotep's son, co-ruler, and eventual successor, Akhenaton. Yet the next kings in line, Tutankhamun and Ay, returned to this city. Further excavation will hopefully reveal more about this dramatic and wealthy time in Egyptian history.

Burials reveal more about Egyptian life before the pyramids

The Giza Pyramids are about 4,500 years old, as National Geographic states. But a civilization doesn't simply spring up and go about building edifices nearly 500 feet tall. Many people lived during the pre-dynastic period of ancient Egypt, generations before the pharaohs. Per Britannica, this extra-ancient period of history saw a few different cultures, many of which didn't seem worried about centralizing authority. Perhaps because of their simple structures and largely unadorned graves, there remains much unknown about some of the earliest Egyptians.

A 2020 discovery may help change that obscured state of affairs. According to Ahram Online, an Egyptian team announced its discovery of 83 ancient graves that year. And when we say ancient, we mean well and truly old, even as far as pharaoh Khufu of the Great Pyramid was concerned. The burials, some of which sported unique clay coffins, were about 6,000 years old and date from what's now called the Buto period. Per Egypt Independent, Buto was an ancient city in the north of Egypt, traditionally known as "Lower Egypt" given the south-to-north flow of the Nile River, as described by National Geographic. Other graves are slightly younger, dating to the Naqada III period, which lasted from about 3200 to 3000 B.C. By the end of this era, Egyptians were likely experiencing the first rumblings of political organization that eventually led to the rule of the pharaohs for many more generations (via "The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt").

A group of megatombs wowed Egyptologists

In recent years, Saqqara, an ancient necropolis that's stunningly vast, has proved to be a rich site for archaeologists. It was even a tourist attraction for many generations, though it was in rough shape by the 19th century, according to Smithsonian Magazine. Modern Egyptologists have continued making remarkable new finds there, from tombs to unique animal mummies that included a lion cub and a mongoose.

It wasn't until September 2020 that a team started to uncover the so-called "megatombs." These burial places were dominated by gigantic coffins made out of carefully carved and decorated wood. Inside one tomb was a beautifully decorated coffin that proclaimed the occupant was a woman named Ta-Gemi-En-Aset. Nearby was a similar coffin bearing a man named Psamtik, and beneath his burial were even more remains. Eventually, excavators unearthed well over 100 coffins in the largest grouping of burials ever found in Egypt. Originally, group burials became common when the kingdom faced serious political instability. Though Ta-Gemi-En-Aset and Psamtik lived during a resurgence of Egyptian power, by that time group burials were the norm.

Per Smithsonian Magazine, this may have also been linked to the worship of long-dead royals. Being buried near a big-name personage may have conferred protection on the dead. Indeed, the whole Saqqara complex was a pretty desirable piece of real estate, even if mortuary priests resorted to cramming coffins into pre-existing tombs.

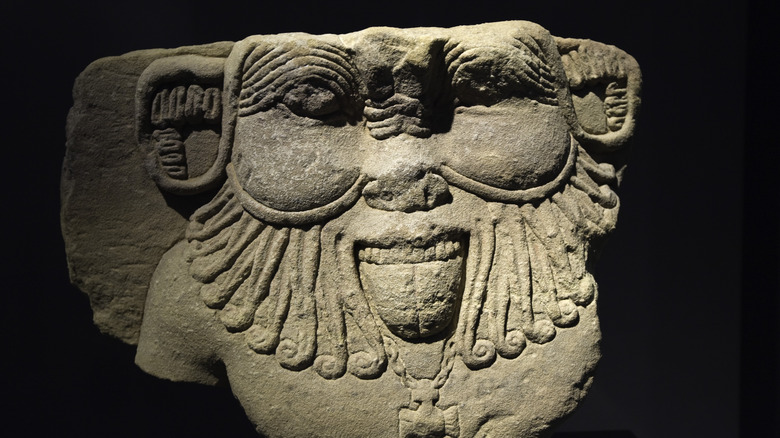

Evidence of a cult was uncovered near Giza

It's no secret that many, if not most, of the pharaohs thought pretty highly of themselves. They lived the good life, dining on fine foods, decking themselves out in rare jewels, and telling people to build massive monuments dedicated to their legacy. According to the World History Encyclopedia, they also frequently proclaimed themselves to be nothing less than gods, given the weighty task of maintaining cosmic order and managing the regular humans in their realm. It was a tough job, likely full of equal portions duty and partying, but someone had to do it.

With all that high-flying rhetoric about divinity threaded through Egyptian history, it's no wonder that some rulers were worshipped after their death. In 2022, further evidence was uncovered that revealed more information about an especially long-lived cult centered around King Teti, who was buried in a pyramid in the Saqqara necropolis more than 4,000 years ago, as Zahi Hawass told NBC News. It apparently wasn't an especially restful tomb, however, as people clamored for 1,000 years to be buried near him after his death.

Evidence of Teti's mortuary cult had been available for years, per the American Research Center in Egypt, Northern California Chapter. Yet the new find reveals even more about how securing a spot near Teti was thought to confer protection on the deceased, even if they were only a humdrum rich person and not a semi-immortal god-king.

Excavators found new sarcophagi near Saqqara

By 2022, it was already abundantly clear that Saqqara, as far as Egyptologists were concerned, was one of the hottest places in the world. The ancient necropolis was teeming with burials and grave goods, not to mention active excavations, and it has hardly been depleted. In May that year, as CBS News reported, archaeologists revealed yet another massive find, this time an estimated 250 elaborately decorated coffins. It was the fifth major reveal from Saqqara since the site had begun getting serious archaeological attention, in 2018.

As impressive and tantalizing as a mound of unopened sarcophagi may seem on its own, there was more within the major discovery to draw attention from across the globe. The reveal included about 150 statues of different ancient gods, including major figures like the underworld king Osiris, his wife Isis, and the goddess of love and sensuality, Hathor. One grave even contained well-preserved wooden statues of the goddesses Isis and Neftis, posed to mourn the dead individual and with gleaming gilded faces.

Previously, as CBS News noted, archaeologists had assumed that the site was primarily dedicated to the goddess Bast, most often depicted as a cat. But previous finds brought that assumption into question — they included not just a wide array of votive figurines but animal mummies as well. This new cache of coffins and religious objects makes it clear that there's a more complex picture of Saqqara waiting to be revealed.

A scroll may reveal more about the Book of the Dead

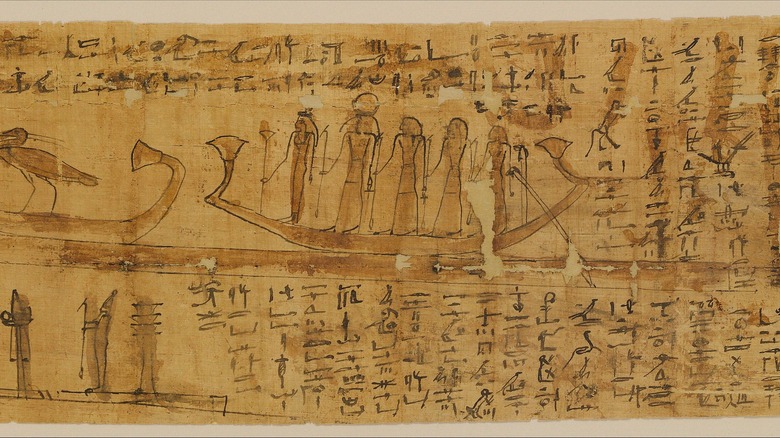

Among the May 2022 trove of about 250 coffins excavated at the Saqqara burial complex was one particularly special find. According to CBS News, one sarcophagus contained a powerful and utterly fundamental text known as the Book of the Dead.

Despite the ominous name, the Book of the Dead was a big deal for Egyptians. It's actually a collection of texts by multiple authors, as the American Research Center in Egypt reports. All forms of the Book of the Dead contain spells and advice for the dead person, who was expected to make a dangerous journey to the afterworld. Quotes from the Book of the Dead are so important that they're often found in mummy wrappings, on tomb walls, and inscribed into coffins. With the help of the spells, the deceased would hopefully make it past a series of challenges to spend their afterlife chilling with the gods.

According to Live Science, the person buried with this 13-foot scroll was a man known as Pwkhaef. He's not in possession of the whole text, but a significant excerpt known today as Chapter 17. Per University College London, Chapter 17 is one of the longest parts of the book and strikingly compares the dead to major deities. Given how central the Book of the Dead is to Egyptian belief, a new copy of any portion of it can reveal more about how these ancient people thought about life after death.

A forgotten queen was discovered

Many Egyptian royals seemed preoccupied with their legacy. Ramses II certainly appeared to think he was Ramses the Great during his lifetime, if his zeal for building monuments full of oversize self-portraits is any indication. Ramses may have been the pharaoh with the most building projects to his name, per National Geographic, but he definitely wasn't alone in his self-regard. Across Egypt, any number of tombs, statues, stelae, obelisks, temples, palaces, and more sport the names of the rulers who ordered their construction.

So it's all the more strange that some of them still managed to be forgotten, or at least partially so. Take the semi-mythical Scorpion King, who was a real pharaoh that managed to unite the disparate fiefdoms of early Egypt, but whose name still evades us (via Los Angeles Times). If even he could be lost to time, where's the hope for less-flashy royals, like the queens of Egypt?

But as a recent discovery made clear, names and identities can resurface. As Ahram Online reported in January 2021, Egypt's antiquities ministry and Dr. Zahi Hawass announced another round of discoveries at the Saqqara necropolis. Among the many finds was a mortuary temple dedicated to Queen Nearit, wife of the cultified King Teti. She's also known as Neit, as CBS News reported, but it's clear we're talking about the same woman. Whatever you call her, this queen is all the more remarkable since, as Hawass admitted, he'd never known she existed.

Mummies revealed a forgotten chapter of tattoo history

Elders may like to complain about inked-up folks these days, but tattooing has been around for a very long time. According to the Wellcome Collection, the oldest known evidence of tattooing dates from around 5000 B.C. in Japan. Otzi, the Alpine "Iceman" mummy who died around 3,300 B.C., is the oldest confirmed person to sport tattoos — a whopping 57 of them, in fact.

So tattooing likely wasn't all that shocking to the ancient Egyptians. As a 2022 study published in the Journal of Egyptian Archaeology argued, the practice may have even been considered essential. Researchers found figurines with tattoo-like markings and two female mummies with identifiable tattoos in the ancient village of Deir el-Medina.

As one of the study's authors, bioarchaeologist Anne Austin, told Live Science, finding tattooed mummies is actually pretty unusual, as imaging techniques have a hard time uncovering the markings beneath linen wrappings, and archaeologists now very rarely unwrap mummies. But Austin's team was able to describe the remains of two tattooed women: one whose left hip sported an image of Bes, a dwarf-like god, and another who was marked with the protective Eye of Horus and possibly another depiction of Bes. The imagery suggests that these tattoos were meant to protect women as they moved through the perilous time of pregnancy and childbirth. This discovery adds to a small but growing body of evidence that ancient Egyptians were definitely down with tattooing.

A sealed tomb contained surprising gold artifacts

Many ancient Egyptians loved gold. For proof, look at any royal burial that hasn't been looted to oblivion. The spectacular 1922 excavation of Tutankhamun's tomb of Tutankhamun's tomb uncovered a horde of golden artifacts that surely captivated the ancients as much as it did us. Yet Egyptians of old and modern folks may have differences of opinion here. Both groups clearly appreciate glittering jewelry, but chances are that few people nowadays are keen on golden tongues.

In late 2021, a Spanish team opened a 2,500-year-old tomb south of Cairo. Archaeologists told The National that the find was especially exciting, because the tomb was still sealed. Inside was a male mummy in a stone sarcophagus and hundreds of small shabti figures meant to serve the deceased in the afterlife. Another tomb, belonging to a woman, had been broken into. Just outside these burial places, archaeologists also found three golden tongues from the more recent Roman occupation of Egypt. Unusual as it may seem to us, the ancients felt they were vital in allowing the dead to communicate with the god Osiris.

Given all of the incantations and other pronouncements necessary to pass divine muster and make it to paradise, why not give a dead loved one an advantage? Even toddlers were included — an extra-small golden tongue was part of the discovery. They're part of only a small group of similar artifacts that could reveal more about a late period of ancient Egyptian history.