Duat: The Story Of The Egyptian Underworld

Every religion out there has its own version of an afterlife. While most modern religions are pretty self-explanatory with what happens when you die, whether that be hell, heaven, purgatory, or some hike across all three, the ancient religions have their own set of destinations. Norse mythology supports an assortment of afterlives, from Asgard to Helheim, while Greek mythology sends most to the realm of Hades (though it's not all bad down there, depending on where you end up).

For ancient Egyptians, their version of the afterlife has been evolving since the Predynastic period from 6000 to 3150 B.C.E., according to World History Encyclopedia. Even back then, people believed in the immortality of the soul — it was just a matter of what actually happened to it. As the idea of the afterlife developed through the Early Dynastic period and into the Middle Kingdom, beliefs took shape and culminated in the New Kingdom, where they were fully fleshed out. The end result varies, but most versions point to a journey through the Duat, where the gods would judge the soul.

Among the many differences between the Egyptian afterlife and that of other mythologies, the biggest one is the sheer number of ways a soul could spend eternity. First, though, it had to get through the Duat, and here's how that was accomplished.

Living life in preparation for death

The average Egyptian had a very interesting relationship with death. All of life adds up to death, so in a way, that's all life was to ancient Egyptians — a trial towards what happens afterlife.

According to World History Encyclopedia, Egyptians had no need for adventure because they were so happy at home, bettering their immediate surroundings. Their reasoning was that the afterlife was largely accepted as a mirror image of their first life. The better their first life, the more they'd want to return to it for all eternity in their second life. Of course, then there's the matter of mummification after death. The Australian Museum walks through the entire process of mummification and preparing the dead for the afterlife. It was a lot of work that earned the ancient Egyptians a reputation of being "obsessed" with death (per World History Encyclopedia), but in reality, that's what life was.

Another key distinction that separates Egyptian death from most other religious deaths is the belief that it was not the end of life — just an interruption of it. According to the Canadian Museum of History, that's why they mummified in the first place — so that their body would be preserved when the soul returns from the trials of the afterlife.

The book of the dead

Knowing what lay ahead after death, the Egyptians knew they had to be prepared. Almost like a version of Dante's "Inferno," the soul had to make a dangerous trek through countless obstacles, passing through the judgment of numerous gods, all in an effort to ensure that eternity was spent in a happy place and not mired in eternal nothingness. Needless to say, a lot was at stake when the soul set off on this journey.

To be prepared, Egyptians created the book of the dead, which was actually just a scroll on papyrus. This book was absolutely vital to the soul's ability to pass through all the different obstacles. It contained essentially a walkthrough full of everything that needed to be said, done, and accomplished in order to get through the tests of the Duat. There were monsters everywhere in the afterlife, tests meant to knock the soul off track, and if you weren't ready, it was easy to get lost. However, there wasn't just one book. John H. Taylor, British Museum's funerary archaeology expert, said (via History Extra), "There was a pool of texts [around 200] from which you could choose, but no known manuscript contains every known spell."

These books were placed in the coffins of mummified remains, though not in everyone's — only the upper classes could afford the required guidebooks.

The ka and the ba

The physical body itself played a big role in the afterlife, though it wasn't an active role. It would be sent on a solar bark (a boat) across the Duat, and throughout the journey, the ba — that's the manifestation of the ka, or the soul — would have to return to the body periodically, where it would rest and recover for the next stage of the journey (via History Extra).

Each day, the ba would go on its journey throughout the Duat, facing the tests and challenges required of it. Often that meant fighting monsters, appeasing the gods, solving puzzles, and passing various trials. And there were two parts to this journey, one for the body and one for the soul. For the body, it had to be mummified so well that it wouldn't deteriorate while the ba was away, and for the ba, it needed to pass through its trials successfully so it could return to the body. After all, according to "Journey to the Resurrection" by Jiri Janak, the ba is the life-giving force that the body requires.

If either portion of the journey derails, the whole thing falls apart — the soul fades into eternal nothingness, and the body decays as all bodies do.

The connection to the night sky

The Duat itself is something of a controversial subject among discussions of the Egyptian afterlife. While it is generally meant to refer to the afterlife itself, there is also a meaning that connects it with the stars and the cosmos, according to Sylvia Zago's investigation of the Duat in "Imagining the Beyond."

According to Zago, the Duat may originally have referred to only one specific location within the journey of the afterlife, but it was later conflated to refer to the entire journey. The link to the cosmos brings about the other connectivity with the Duat — that the afterlife itself, for Egyptians, takes place in the stars, given the deep connection the gods had with astrology. In fact, the details can all be connected, as seen in "Origin of the Hour and the Gates of the Duat" by R.A. Wells, who parallels the gates of the underworld with the various arcs of the stars in the night sky. In a sense, all the gates that the ba passed through in the afterlife could be seen in the various constellations.

Whatever the case, the Duat itself characterizes the trials of the soul — the portion that requires something of a quest, and without it, the soul is lost to eternal nothingness.

The gods role in life and death

Unlike the Greek gods, who really couldn't care less about any given mortal's journey through life and into death, the Egyptian gods took a very active role in what happened along the way. While it was mostly an effort to ensure that everyone ended up where they belonged, it still allowed for the free will of any given individual while providing some guidance along the way.

According to World History, the gods were considered an individual's close friends. Hathor was always close by to provide shade in life, while Selket, Nephthys, and Qebhet greeted newly arrived souls in the afterlife and ensured their safe transit. And it wasn't just arbitrary transportation, like Charon in the Greek underworld; Qebhet would bring new souls water and nourishment when they were weary. Then there were Anubis, Thoth, and Osiris waiting to judge souls among the host of other gods. While there were "trickster" gods like Seth in Egyptian mythology, most of the gods were pretty straight-laced and dedicated to their roles in life and death.

Depending on how the judgment went, you could be facing an afterlife full of more close contact with the gods. Some souls remained in the house of Osiris for eternity, while others cruised with Ra in his solar barge. Of course, some were eaten by Ammit, but only the unworthy. Everyone else faced a pretty healthy, happy relationship with the gods for all of eternity.

Passing through the gates

This is the part of the journey that feels like something out of a video game. When the ba was passing through the various stages of the afterlife, one of the key components was facing monsters and "bosses" that had to be overcome in order to pass on to the next "level." Each gate was protected by a deity, and they had to be beaten in a very specific way (History Extra).

That's where the various books of the dead came in handy. They contained instructions on how to beat each deity and what spells to cast to move on. For instance, the example that History Extra provides is for when the ba approaches the sixth gate — spell 146 gives the secret formula. All you do is say, "Make a way for me, for I know you, I know your name, and I know the name of the god who guards you — 'Mistress of Darkness, loud of shouts; its height cannot be known from its breadth, and its extent in space cannot be discovered. Snakes are on it, of which the number is not known; it was fashioned before the Inert One' is your name."

But according to spell 144, you could also approach the gate by claiming, "Mine is a name greater than yours, mightier than yours upon the road of righteousness." Since no two books of the dead were the same, they each provided different instructions.

The 42 Judges

After passing through the gates and defeating the deities, Anubis would guide the ba into the Hall of Truth, where it would wait in line to be judged once and for all (via World History Encyclopedia). It wasn't just a simple matter of being judged, as can be found in the Christian afterlife, where you're given a thumbs up or thumbs down and sent on your way to whichever eternity matches your soul.

In the Hall of Truth, the 42 judges would convene and discuss the worthiness of the ba and whether it deserved to continue existing. Among these 42 judges were practically the whole pantheon of Egyptian gods, including Ra, Hathor, Horus, and Isis. Names like Crusher of Bones, Stinking Face, Eater of Shade, and other deities you probably would never want to meet. They were meant to be this way in order to intimidate the soul and evoke the true essence of what made it worthy or unworthy.

Presiding over the whole ordeal was Osiris, who would deliver the verdict when it was reached.

The heart is judged

There are many interpretations as to what happens in the Hall of Truths, including if that's even what it was called (some call it the Hall of Ma'at), but perhaps the most popular version states that after answering the questions of the 42 judges, the soul could up its odds of good news by reciting the "Negative Confession" (per World History Encyclopedia). This confession included 42 sins that one was expected to have not committed, including stealing, causing someone to weep, causing someone to go hungry, and more. The ba would claim to have not done these things in front of all the judges.

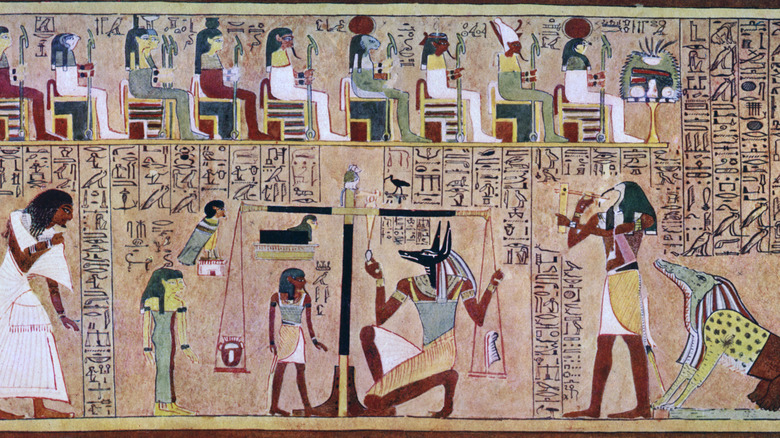

If the 42 judges liked the answers and believed the confession, the heart (the vessel of the soul) would then be judged against the feather of Ma'at, the Egyptian goddess of truth, justice, harmony, and balance (via History Extra). The heart would be placed on the scale by either Osiris or Anubis, depending on who you ask, and there it would be weighed, literally, against the truth. If the scales balanced, that meant that you were honest and truthful and worthy. If they didn't balance, that meant you had lied and were unworthy.

That's not the end of the road, however. There were still plenty of options that awaited the judged soul, even if the scales didn't balance.

Eaten by a crocodile

Assuming the scales don't balance, there are only one of two options. In one scenario, your soul gets eaten by the god Ammit, also known as the devourer, who has the head of a crocodile, the body of a lion, and the legs of a hippo, according to History Extra. Once the soul is consumed, it dies the second death and disappears into nothingness. However, there is a way to subvert this less-than-savory outcome, assuming you have the right book of the dead. Spell 30B provides an easy out if the judged says, "O my heart of my mother! O my heart of my different forms! Do not stand up as a witness against me, do not be opposed to me in the tribunal, do not be hostile to me in the presence of the Keeper of the Balance."

According to John H. Taylor, British Museum's funerary archaeology expert (via History Extra), "Even if you had lived a bad life you could get away with it by using this spell, which prevents your heart from spilling the beans to the gods. This was the first time in history when you see the idea that your fate after death was dependent on your behavior when you were alive. However, it was not carried through to its logical conclusion – because you could cheat your way around that particularly tricky moment."

Which is kind of like a "Get Out Of Jail Free" card in Monopoly, just with higher stakes.

Different versions of eternity and paradise

If everything went well during the ba's journey through the gates of the Duat, and if the 42 judges saw no qualms in the heart/soul of the dead, then the ideal ending point would be the A'Aru, or Field of Reeds. According to World History Encyclopedia, this was a glorified version of what life had been like, justifying why Egyptians spent so much time in life perfecting their surroundings — they wanted to come back to this eternally.

That wasn't the only possible outcome, however. Since no books of the dead were the same, they all had different ending points. The Field of Reeds was one, but there was also the possibility of spending eternity with one god or another. History Extra provides two examples, both of which sound pretty decent. One was to spend the afterlife cruising through the sky with Ra in his sun boat, and the other was to spend eternity with Osiris in the Duat, enjoying a front-row seat of all the trials faced by other ba.

Whichever ended up being the case, it beats being devoured by Ammit.