The Iri Of Ancient Egypt Was Given A Job Title Unlike Any Other

The ancient Egyptians possessed impressive engineering and were renowned for their knowledge of human anatomy (via Ancient Origins). We know that they performed surgical and dental procedures (via the Journal of Vascular Surgery). They appreciated the importance of diet and created medications and prosthetics. Great importance was put on cleanliness, a medical practice not fully adopted by European physicians until the mid-20th century (via World History).

In this era, humans capable of advanced logic and scientific reasoning were surrounded by a culture of ever-present deities. Diseases were seen as punishments inflicted upon humans by gods or evil external forces (via the American Journal of Nephrology). A physician was a combination of a doctor, priest, apothecary, and magician all rolled into one.

By examining bodies and internal organs in healthy versus diseased states, ancient Egyptian physicians deduced that purging the body of harmful elements would return it to its natural state (via the American Journal of Nephrology). Specialists were responsible for "ridding the body from noxious material and influences." That's why one particular type of physician was responsible for the cleanliness of the pharaoh's rear end.

Swnw handled wekhedu

With both reason and religious thinking, people from ancient Egypt examined the human body to understand the various states of disease. Physicians were also considered priests (via "Ancient Egyptian Magic" by Bob Brier, Ph.D.). Swnw or sounou were medical experts who specialized in removing disease from specific parts of the body (via Ancient Origins). As they understood, each part of the body was governed by a patron god, and recovery was dependent on honoring them as well as expelling diseased material (via A History of Medicine).

Illness was caused by a material called wekhedu. Historians have struggled to define this ancient concept. Some have thrown in the towel and let context decide its meaning (via "Ancient Egyptian Medicine" by John F. Nunn). Examples of wekhedu include disease-state tissue, purulence, mucus, or excrement (via the Journal of Vascular Surgery). These disease-causing agents could spread between areas of the body and people (via "Ancient Egyptian Medicine" by John F. Nunn). Thus, eliminating wekhedu from the body was essential for health (via the Journal of Vascular Surgery). An important source of wekhedu to keep healthy was the anus or phywyt.

The brown star of egypt

The phywyt held a special role in ancient Egyptian pathology (via the Journal of Vascular Surgery). The hope was that a clean rectum would prevent disease (via Ancient Origins). Dedicated texts and treatments took a nuanced approach to phywyt health. The phywyt wasn't just a constant source of wekhedu being expelled from our backsides. A term distinct from wekhedu, hes, translated as healthy feces (via Ancient Egyptian Medicine). The existence of this term suggests refined definitions within the ethnomedicine practiced by these people. A neur pehuyt was the ancient Egyptian equivalent of a proctologist and cared for issues of the phywyt and lower intestines.

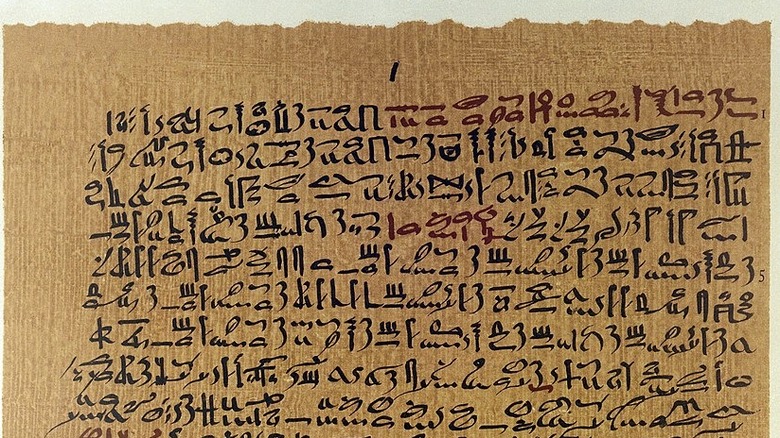

The most insightful and comprehensive medical text surviving from ancient Egypt is the Eber Papyrus (via Ancient Origins). The 68-foot-long roll of short cursive hieratic type explores concepts of physiology and anatomy. It contains 842 treatments for illnesses from zoonotic diseases to what was likely diabetes. It also contained various anal remedies. One sphincter-chilling therapy included 1/32 onion meal, 1/32 tail of a mouse, 1/14 honey and 1/3 water, strained and consumed for four days (via The Papyrus Eber). Another remedy says rolling the fat of an antelope and caraway into a pill and plugging it up the rectum can reduce the smarting of an anus. Other anus-friendly ingredients included ox bile, eggs, cow horn, wonderfruit, or the guts of a goose.

Bird, god, and enemas

The Ebers Papyrus also contains the first written description of enemas in human history (via Ancient Origins). The ancient Egyptians used enemas frequently to rid a sick person of wekhedu (via Ancient Egyptian Medicine by John F. Nunn). A dedicated section explains how ancient people inserted gas, liquid, or medicine into the body via the anus to remedy constipation (via Ancient Origins).

According to "A History of Medicine," the ancient Egyptians believed the god Toth or Thoth was the creator of the enema. This god of healing and medicine had the head of an ibis (via Medicine in Ancient Egypt). The ibis nests along the coastal wetlands of the Nile (via Archive of Oncology). It's said people observed this bird preening, using its long curved beak to flush its colon with water. Perhaps through observations and the close connection between this bird and health, ancient people adopted enema therapy (via Ancient Origins).

One vivid description from the Eber's Papyrus instructs physicians to "rise early ... to see what has gone down from his anus ... If you examine him after doing this and something goes down from his anus like porridge of beans..." The author John F. Nunn of Ancient Egyptian Medicine, abruptly ends the translation and acknowledges the point has been made. This 1500 B.C. description might be the earliest record of a physician checking the stool of a patient with food poisoning.

Guardian of the royal rectum

The ancient Egyptian title Iri has a few interesting meanings. There's a Guardian or Shepard of the Royal Rectum as well as a Protector of the Anus (via Mummies, Disease and Ancient Cultures). The Guardian of the Royal Rectum or Iri was the neru phuyt that served the pharaoh's enemas (via Ancient Origins). It's unknown and debated if this position was similar to a proctologist or a glorified enema giver. Still, either way, just touching the living god/ruler was an immense honor (via the Journal of Vascular Surgery). So, just imagine the clout that came with servicing that rear end (via Ancient Origins).

We know of one famous Iri named Irynachet who lived in 2200 B.C. Giza. They were a senior physician of "the great house." An ornamental door commemorating this individual describes their various lauded positions. Irynachet was one of the many royal physicians (via Mummies, Disease and Ancient Cultures). Their titles included Physician of the Belly, Physician of the Eyes, and Protector of the Anus (via Ancient Origins). Iri was a distinction perhaps to avoid the implication that the royal palace would need a lowly neur phehuyt/enema giver (via Ancient Egyptian Medicine by John F. Nunn). And for the anuses of living gods, what would be more fitting than a golden cannula to serve the pharaoh's enemas (via Ancient Origins).

The chester beatty medical papyrus

The Chester Beatty Medical Papyrus from 1200 B.C. is another well-known medical text and contains an anus affliction section (via British Medical Bulletin). It prescribed treatments for prolapse, hemorrhoids, and "various anal maladies." Some are oral and other suppositories, enemas, or ointment for "local application to the anus." Some of the prescriptions from the Chester Beatty Medical Papyrus concerning the anus remain to be translated or perhaps even understood (via Ancient Egyptian Medicine by John F. Nunn).

The Beatty Papyrus notably contains little to no references to magic, which is rare in ancient Egyptian documents (via British Medical Bulletin). However, some Egyptologists believe supernatural elements were such a part of every day it was unlikely separable from medicine. Religious meaning could be subtle. Certain words, procedural steps, or ingredients could be inextricably linked with various deities. These references may not be obvious to modern audiences (via The University of South Africa). Though their religious beliefs likely pushed medical practice in some different directions, it didn't prevent the ancient Egyptians from developing one of the most effective medical systems in the ancient world.