The Deadliest Smogs In History

Although it's frequently repeated that smog is what happens when an area is covered with a combination of smoke and fog, that's kind of only partially true. While that's what it started out to mean, the Asthma Society of Canada says that the definition has changed a bit.

Today, smog is defined as a combination of ground-level ozone — made by the reaction of pollutants like nitrogen oxide with other, organic compounds — and fine particulate matter, or airborne particles. Too much smog can be deadly, and in fact, even a little can be deadly, too, especially when it's inhaled by someone with chronic conditions such as asthma or other respiratory ailments.

Scientists have known it's a bad thing for a shocking amount of time. Way back in the ninth century, Down to Earth says that people in the U.K. started burning what's called "sea coales." Doing History in Public adds that this was coal that was eroded away and then washed up on the shores. With deforestation rampant, people turned to burn this seemingly inexhaustible source of fuel. As coal does, these "sea coales" covered London in such a thick blanket of pollution that Edward I banned the burning of sea coal, and even carried out at least one execution for defying the law.

That was back in 1307, and, perhaps unsurprisingly, when people had to choose between being warm and perhaps being dead, they often opted to risk it. Have we gotten smarter? Nah.

1948: Donora, Pennsylvania

Getting accurate death tolls for smog events is difficult because they don't just kill immediately — smog leaves some with slow-burning, life-long health complications. That said, let's look at Donora, Pennsylvania. According to research published in the American Journal of Public Health, 20 people died during a smog event there, and 43% of the population (or, about 6,000 people) suffered lifelong consequences from it.

So, what happened? Donora is the home of two massive industrial plants: the Donora Zinc Works, and American Steel and Wire. Smog was pretty normal, so when it settled in during the final days of October 1948, it was business as usual. Until suddenly, it wasn't.

Charles Stacey survived it, and recalled (via National Geographic) turning on the radio to hear about a Pennsylvania town "where people are dropping dead." He wondered where it was, and found out later that it was his own neighbors who had watched a high school football game, participated in a Halloween parade, and then started to die. The first died at 2 a.m. on October 30, and over the course of the next 12 hours, 17 more would die. Over the following decades, residents would suffer from higher-than-normal instances of things like heart and respiratory disease, and cancer.

The cause — along with, of course, the pollution — was a temperature inversion that trapped cold air beneath warm and sandwiched the pollution between the town and the upper, warmer air. The disaster ultimately kick-started the passing of the Clean Air Act.

2010: Moscow, Russia

The summer of 2010 was one of the hottest in Moscow's 1,000-year history, and life there was pretty dire. In addition to the heat, more than 550 wildfires had started to burn around the city, which caused the entire area to be blanketed with deadly smog. According to the AFP, the city's daily mortality rate rose from around 370 people to 700. Moscow's head of city health revealed (via CNN) that although they had room in morgues for 1,500 people, 1,300 of those spaces were already filled — and people were still dying.

The Russian meteorological service described a dismal scene: "The air will remain filled with products burning in forest and peat fires, and with toxic emission coming from motor vehicles and industrial enterprises." Senior citizen Rimma Zgal was a little more straightforward: "I don't know how long we will last."

According to officials, smog and particulate matter were at 3.4 times a level deemed safe by August, and there were terrifying warnings that once it was inhaled, the human body had next to no chance of getting rid of it. Carbon monoxide levels peaked at a shocking 6.6 times acceptable levels. Just how many deaths were caused by the smog is difficult to tell. Upwards of 104,000 people fled the city and the smog, but according to Reuters, the cost in human lives was catastrophic. Between the wildfires, heat, and smog, the city's death toll had, by October, surpassed the previous year by 56,000.

19th century: London, England

Precise numbers of those killed by the consequences of 19th-century smog are understandably hard to come by, but what we do know suggests that particularly bad smog events in London killed hundreds of people ... at least.

The Met Office says things were bad from the earliest days of the Industrial Revolution, and records of smog events go back to at least 1813. In December of that year, it got so bad that it was impossible to see across the street for nearly a week. Another happened in 1873, and again in 1880, 1882, 1891, and 1892. Each time, the death rate rose, and records suggest that in 1873, it rose by around 40%.

What does that mean? According to the EPA, recent research suggests that somewhere around 268 people died from smog-induced bronchitis. They also say that some of the events lasted way more than a few days, with one smog event lasting from November 1879 to March 1880. That was a suffocating, choking, smog spanning five months, and that's pretty terrifying.

The area that was typically impacted the most was London's East End, where people, residences, and industry were packed together with the kind of claustrophobic precision that would make anyone's heart skip a beat. It was during this era, says the Museum of London, that the city's green spaces were established. Even today, they're called the Lungs of London.

1930: Meuse Valley, Belgium

While Meuse Valley, Belgium, might sound like a quaint, idyllic place nestled into the wild European landscape, the truth is a little more complicated. In 1930, it was home to a series of 27 massive factories, including metal and glass works, ceramic factories, and numerous zinc and superphosphate manufacturers. Paints a different picture already, doesn't it?

Between December 3 and 5, the perfect storm — or lack thereof — settled over the valley. The wind disappeared, mist hovered along the mountaintops, and the smog and pollutants from the factory started building up under the cap of mist. By the time the mist cleared and the wind came back, 60 people were dead and several thousand more suffered severe respiratory episodes. At the time, reports — like the one cited by The New York Times — claimed that the smog's sulfuric acid content was what made it so dangerous, but other studies found there was something else going on.

A report published in the Journal of Industrial Hygiene and Toxicology found that in addition to the sulfur, the majority of the factories in the valley were also putting out silicon tetra-fluoride, and some of the non-human casualties showed symptoms of chronic fluoride poisoning. Vegetation died, and cattle were particularly impacted. Another study from the Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine found cattle were one of the most susceptible to this type of poisoning, developing lesions in their bones and teeth.

1991: London, England

When government committees meet in secret, it's safe to say that it's not because things are going great.

In 1994, the Independent reported on a secret meeting of government health advisors in the U.K. They were discussing just what had happened three years prior, when a high pollution and smog event had left at least 160 people dead, and many, many more with chronic lung problems. The incident in question happened between December 12 and 15, 1991, with environmental monitoring equipment registering levels of pollution higher than anything that had ever been recorded. Jon Bower was one of the scientists doing the monitoring, and said, "The first thing you say to yourself is, 'Is this real?' The reading went right off the top of our computer graph."

A report from epidemiologists at London's St. George's Hospital (via New Scientist) confirmed the deaths from the smog event, which happened after traffic-related pollutants built up over the city during a streak of cold, wind-free days. And here's where the meeting-in-secret part comes in: It was also found that the government-issued warnings were sorely lacking, with the Department of Health telling residents that there was no need to wear a mask or worry about breathing the air during everyday, outdoor activities ... a non-warning given in spite of the fact they knew the air contained about twice the nitrogen dioxide as deemed safe by the World Health Organization.

2016: China

It's time to talk about the smog event that descended over China in 2016, but it's difficult to find numbers relating to casualties and health issues for a terrifying reason: According to CleanTechnica, the smog impacted around half a billion people and 24 big cities. And that was against the backdrop of normal, everyday levels of smog: An estimated 200 million people living under the blanket of potentially deadly air every single day.

The Guardian reported that things were so bad that hundreds of thousands of people fled, either to smog-free regions in China or abroad. Yang Xinglin was one of them, and explained: "You ask me why I left Beijing? It's because I want to live." Saying conditions were deadly wasn't an exaggeration. As reported by The Diplomat, pollution readings would eventually rise to a level that was 50 times higher than what the World Health Organization has ruled as being safe. Schools and businesses closed, flights were canceled, and doctors prepared for the worst.

While numbers relating to that smog incident are scant, there are other numbers to talk about — including one published in 2016, just a few months before northern China was enveloped with smog. According to a collaborative study between China's Tsinghua University and Boston's Health Effects Institute (via The New York Times), 366,000 people died of smog-related causes in 2013. Furthermore, research later suggested (via Phys.org) that the total number of smog-related deaths between 2000 and 2016 was around 30.8 million.

1952: London, England

Anticyclones, as defined by the UK Centre for Ecology & Hydrology, are a weather phenomenon where rotating air is pushed to the ground to create a high-pressure area with little in the way of wind. It was an anticyclone that was responsible for the five-day disaster known simply as the Great Smog, and it's a chillingly perfect example of how it can be difficult to determine a specific death toll. When the smog happened in 1952, immediate estimates cited around 4,000 dead. The BBC says that more recent research, however, suggests that it was actually closer to 12,000.

The smog descended on December 5 and didn't lift until December 9. National Geographic says the city and people of London would feel the effects of it for decades. It wasn't just smog that settled over the city: As explained by the Met Office, smoke from coal fires combined with other pollutants in the atmosphere, including sulfur dioxide. And that? That's what makes sulfuric acid, which started to fall in the form of acid rain. Visibility was next to zero — pedestrians reported not being able to see their own feet.

One tragic footnote is a sad but perfect example of the domino effect. Among the dead were many of the cattle at the Smithfield market — a major food source for the city. The event kick-started legislation to clean up the country's air, and while there were other smog disasters, it at least got them heading in the right direction.

2005: Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia

In 2005, The New York Times reported Malaysia declared a state of emergency in several areas. Why? Smoke and other pollutants kicked into the air by Indonesia's raging wildfires were drifting across coastal cities and settling there. Malaysia responded by offering to send aid to help put out the wildfires, but here's the thing: The 2005 incident was just one particularly terrible smog disaster in a long line of smog disasters.

Previously, the worst year had been 1997, and at the time, it was decided that one of the most immediate solutions to the problem would be to simply stop publishing findings on air quality. So, maybe not the best idea? But Malaysia was undoubtedly finding itself between a rock and a hard place, as The Guardian reported that the yearly smog events were directly related to Indonesia's inability to put a stop to the destructive wildfires and to the large-scale clearing of forests for commercial agriculture. Add in Malaysia's own industry and open burns, and it's formed an annual smog problem with dire consequences.

What does that mean in terms of numbers? According to Greenpeace, the consequences of air pollution cost Malaysia the equivalent of about 20% of its GDP each year. And the human cost is just as high: It's estimated that there are about 32,000 smog-related and pollution-related deaths each year.

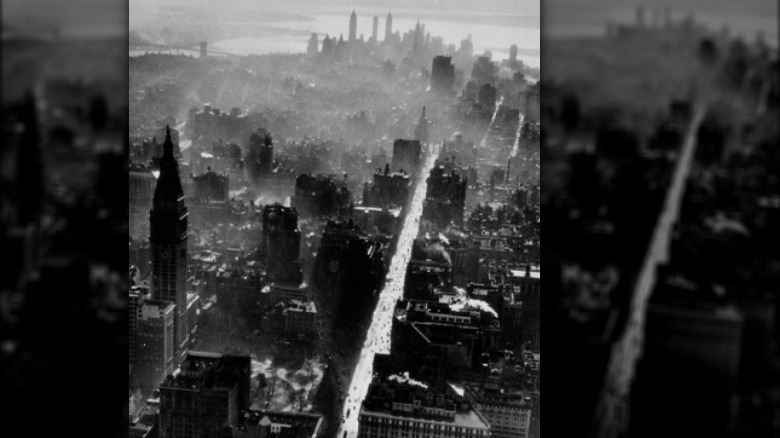

1953 and 1966: New York City, New York

The most shocking thing about the deadliest smogs in New York City — which happened in November 1953 and again in November 1966 — is that when they happened, no one really knew they were in the middle of an environmental disaster.

How is that possible? For starters, The New York Times says at the time, the city was a polluted mess on a daily basis — so, there really wasn't a noticeable difference. Journalist Jim Dwyer recalled growing up in the city in the '60s: "My playmates and I stopped everything when it began 'snowing' ash from incinerated garbage. We chased tiny scraps of partly burned paper that floated in the air as if they were blackened snowflakes."

Yikes. And those incinerators? There were 32 municipal ones, and another 17,000 small-scale ones, run for city apartment buildings. Air pollution was so bad it ceased to be shocking, with one city medical examiner explaining to The New York Times in 1970, "On the autopsy table it's unmistakable. The city dweller's [lungs] are black as coal." Around 200 people died as a result of the smog that settled over the city in 1966, and according to a report written for the EPA, the death toll was about the same for a smog event in 1953. However, it was a full nine years before enough data and death records were compiled to make authorities realize that yes, the city had been particularly deadly on those days.

2013: China

In 2013, China was hit by a particularly hard smog — one that The Guardian reported could be seen from space. On the ground, they described a post-apocalyptic scene: smog blotted out the sun, midday looked like dusk, and the air tasted like chemicals. In a viral music video, a singer asked, "Who is searching in the fog? Who is weeping in the fog? Who is living in the fog? Who is dying in the fog?"

Like many smog events, this one was caused by a temperature inversion that trapped smog over the landscape in a wind-free, high-humidity hellscape. Many fled, but many more couldn't. And here's the thing: Pollution in China is such a problem that it's hard to come up with death tolls for one specific event — even one as bad as what happened in January 2013. There are a few things we know, though, including the heartbreaking fact that a single hospital reported treating respiratory illnesses and conditions in upwards of 900 children that month.

In April of that year, NPR reported a study from Boston's Health Effects Institute. According to scientists there, the annual, smog- and pollution-related death toll in China was a shocking 1.2 million. Those most impacted by the smog include the very elderly — who are dealing with compromised immune and respiratory systems on the best of days — and the very young. Why? Because every year they live under the blanket of smog is another year's worth of pollutants building up inside them.

1948, 1956, 1957, 1950, 1962: London, England

Most people might know the Great Smog of London in 1952, but it's also worth talking about the less deadly but more frequent pea-soupers that gripped the city in other years. Dr. Richard A. Prindle described his experience in the 1962 smog event (via The Long View): "As the airplane doors were opened at Gatwick, the smell of sulfur and coal smoke was overwhelming. One gets used to it, but while walking along the street in London at night, there was a continual metallic taste in the mouth and irritation of the nose, pharynx, and eyes ... like the effect of peeling onions."

History Extra says that by this time, it was well-known just how damaging smog was — and deaths were recorded in each event. Between 700 and 800 people died in November 1948, and that was followed by around 1,000 deaths in January 1956. Then another 750 died in December of the following year and upwards of 200 deaths occurred in January 1959. Fast forward just a bit to 1962, and it's less precise: That year, somewhere between 340 and 700 people lost their lives during a smog event in December.

It's likely that those are vastly underestimated numbers. About 40% of the coal-reliant, industrialized country was prone to smog events, not just London. In 1962, the BBC reported that areas like Leeds and Glasgow were struggling under the same oppressive pollution. The advice given by the Ministry of Health? Stay inside.