The Dark Secret About Being A Silent Film Star

Early Hollywood has a mystique that remains unmatched, even as the decades march on and it recedes further and further into history. Few stars today can match the soft-focus glamor of Greta Garbo, the smolder of Theda Bara, or the daring charm of Louise Brooks, all of whom made waves even before their voices could be recorded onto film. It's easy to get caught up in the nostalgia and pine for the days when the stars seemed almost god-like, and not just denizens of the next tawdry gossip article.

But wistful reminiscences aren't always true, and the glamor of Old Hollywood was often a veneer applied on top of a far more complicated reality. Take the famously reclusive Garbo, who told friends that her life as a star was often frustrating and depressing, and that she longed for a quiet life in her native Sweden (via Sotheby's).

Garbo's isolation is hardly the end of it. Silent film stars faced all manner of hurdles, including persistent racism, homophobia, the erosion of their private lives, among many other tragic stories attributed to Old Hollywood's legendary actresses. And that's well before the first sound films, popularly called "talkies," began upending the film world in 1926 (via The New York Times). As the dark side of silent film stardom shows, perhaps these actors weren't so fortunate after all.

Early film stars got almost no recognition

According to Paul McDonald in "The Star System: Hollywood's Production of Popular Identities," the idea of celebrity had already been established by theater actors in the centuries leading up to the first films of the late 19th century. Yet filmmakers weren't initially keen on making actor-centric narratives, sometimes preferring to wow audiences with special effects, or simply showing something as it happened, documentary-style. Humans were almost an afterthought, though some producers at least called upon already well-known performers, like dancers and vaudevillians, to grace the screen.

According to "The Star System," things changed around 1907 when the growth of the film industry meant that film actors got more regular work. Still, it was hardly prestigious and studios were inconsistent when it came to promoting these emerging stars. One of the first to gain acclaim was Florence Lawrence, who nonetheless started her career as a vaudeville actor and then went mostly anonymous as the Biograph Girl, as per the Bright Lights Film Journal. Though Lawrence would go on to gain plenty of recognition, to the point where crowds swarmed her wherever she went, she was initially part of a system where studios like the Edison Trust declined to name actors, for fear of having to pay them a higher wage (via History).

The first silent film celebs saw their private lives become public

At one point or another, Florence Lawrence may have wished to be anonymous. Sure, she went from being the mysterious Biograph Girl to a genuine celebrity, but that fame came with a serious dark side. As per the Bright Lights Film Journal, Lawrence once attended a premiere where fans reportedly tore the buttons from her coat. Producer Carl Laemmle even went so far as to claim she had died in a street car accident, just to gin up ticket sales for her latest film.

Lawrence eventually slid into obscurity, but other stars would find that their personal lives were up for consumption. According to "The Star System," the first such gossip began circulating as early as 1913, focusing on the stars' glamorous lifestyles. Studio representatives began presenting those private lives as squeaky-clean exemplars of morality, thereby also boosting the reputation of the once grubby film industry.

Early fan magazines tended to burnish the rough edges of potential scandals, too. As per The Guardian, Photoplay magazine reported on the 1920 marriage of Mary Pickford and Douglas Fairbanks, who had ditched their previous spouses to get married. Yet it did so in such a gentle way that it seemed hardly worth commenting on. Not so for Clara Bow's shocking 1928 piece in the same magazine, which gave so many details of her difficult life that fellow actors were alarmed at her precedent. This approach played into more invasive stories as time went on.

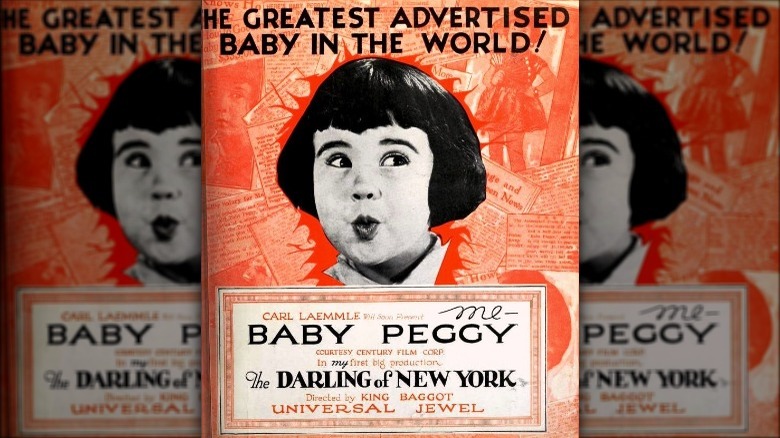

The film industry exploited child stars right away

Child stars aren't new. Rewind to 1760s Europe, where you might have heard of two piano prodigies touring the continent: Maria Anna Mozart and her younger brother, Wolfgang.

The situation wasn't all that different for the child stars of the early film industry. Perhaps the most famous kid of the silent film world is Jackie Coogan. According to Britannica, an 18-month-old Coogan first appeared in 1916's "Skinner's Baby," though his big break was in 1921's "The Kid" alongside Charlie Chaplin. He earned fantastical amounts of money, but later learned that his parents had spent it all. His experience led to the passage of the Child Actors Bill in California, more commonly known as the Coogan Law, which still regulates the contracts of child actors and how their income is managed.

Coogan was far from the only kid to face the unregulated and often uncaring world of Hollywood. Diana Serra Cary, once known as Baby Peggy, told The Guardian that she wasn't formally educated and often faced dangerous situations on set. Her earnings were also frittered away by careless parents, who seemed more interested in putting her to work than making sure that she was educated, safe, or loved. Cary, who died in 2020 at age 101, went on to write at length about her and other child stars' experiences.

Drugs were practically everywhere

As RogerEbert.com reports, cocaine was falling out of favor in the U.S. by the 1920s, but it remained ubiquitous in Hollywood. Rumors swirled about the supposed habits of actors, from overly peppy comedians to exhausted stars who may have taken a dose of something to keep going. Actress Barbara La Marr died at only 29 years old, reportedly after a career spent indulging in all manner of substances. Her son, Don Gallery, told the Los Angeles Times that she regularly consumed heroin, and even went so far as to leave a container of cocaine out in the open on her piano.

La Marr was hardly the only actress to get caught up with drugs. As Stephen R. Kandall writes in "Substance and Shadow: Women and Addiction," Alma Reubens "was arrested for morphine possession" and Juanita Hansen lost her career to addiction (though she managed to survive and worked to help other people suffering from addiction).

Actor Wallace Reid infamously lost both his career and his life in the wake of a morphine addiction, according to E.J. Fleming's "Wallace Reid: The Life and Death of a Hollywood Idol." After a bloody train accident on a film set, a doctor gave Reid morphine to deal with his injuries and to keep working. Even after he ostensibly healed, Reid couldn't quit the opiates. He died on January 18, 1923, of what another doctor said was kidney failure and pneumonia made all the worse by morphine withdrawal (via "Wallace Reid").

If you or anyone you know needs help with addiction issues, help is available. Visit the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration website or contact SAMHSA's National Helpline at 1-800-662-HELP (4357).

Actors risked serious injury for stunts

Stunt performers may have appeared as soon as in 1903's "The Great Train Robbery," as Gene Scott Freese argues in "Hollywood Stunt Performers." Yet, some stars like comedian Buster Keaton insisted on performing some stunts, no matter how dangerous.

According to The Guardian, Keaton did all manner of death-defying stunts, relying on his physical comedy experience from the vaudeville circuit to stay alive. He cited his immense "body control" as one of the reasons he survived. The most famous and terrifying of his stunts comes from 1928's "Steamboat Bill, Jr." There, Keaton stood stock-still as a massive house façade fell on top of him, with only a single open window allowing him safe passage. Only his nerves and some careful calculations kept Keaton alive and three-dimensional.

Keaton may have come out of that stunt whole, but he wasn't always so lucky. He'd been knocked unconscious on set, suffered broken bones, and even fractured his neck during one stunt. Harold Lloyd, another great of silent film comedies, suffered a 1919 accident where half of his right hand was obliterated in an on-set explosion — which made his later stunts all the more impressive (via Vanity Fair). According to The Guardian, other actors suffered frostbite, were caught up in bone-shattering wagon crashes, and even drowned after being thrown from a horse.

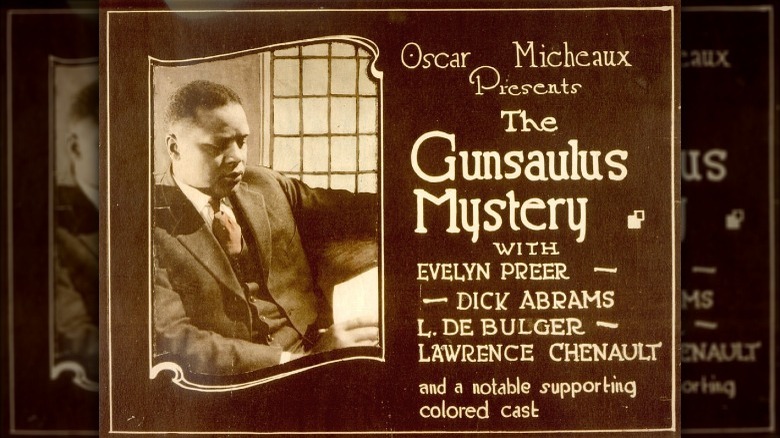

Black actors were often segregated

One of the earliest movie blockbusters, 1915's "The Birth of a Nation," hinged on deeply racist depictions of Black Americans. According to History, reactions to the film included riots, bans, and the rise of the modern Ku Klux Klan. It's no wonder that Black performers were absent from many mainstream Hollywood films.

As the British Film Institute reports, Black filmmakers like Oscar Micheaux and Paul Robeson continued to operate as independent creators outside of the growing Hollywood system. They frequently created race films that catered to Black audiences. Filmmakers had a complicated relationship with this setup, which allowed them to create movies with all-Black casts and sometimes crew, but in a segregated system with low budgets and little access to Hollywood resources. Some also worried that they were playing into stereotypes in order to sell tickets and distribute films. But many felt compelled to take part in the developing art form, creating and distributing stories that spoke to an audience that was neglected by Hollywood. What's more, according to the UCLA Digital Humanities program, filmmakers directly responded to the overt racism of "The Birth of a Nation" with a number of movies including "The Birth of a Race."

As UCLA notes, few of these race films survived, meaning that researchers must rely on things like posters and advertisements to prove that some works ever existed. Yet the independent Black film industry continued operating well after the introduction of talkies, into the 1950s.

Asian actors came up against barriers

Sessue Hayakawa was a skilled, naturalistic actor whose work was a stark contrast to the stiff performances of other stars, as the Center for Asian American Media reports. With his athletic build and smoldering good looks, another thing was abundantly clear: He was a hunk. But Hayakawa's roles opposite white costars often cast him as the villain or a second-ran lover who inevitably stepped aside. Despite the institutional racism, Hayakawa had a long career that saw him establish a production company, work in Europe, and star opposite Alec Guinness in 1957's "The Bridge on the River Kwai."

Anna May Wong was also a bonafide movie star, though she too seemed to be perpetually sidelined. According to the New York Historical Society, she broke through as the tragic lead in 1922's "The Toll of the Sea." Wong's character, Lotus Flower, was an abandoned single mother previously married to a white man, the father of her child (via National Film Preservation Foundation). To keep working, Wong gritted her teeth and continued to take roles that cast her as a pliant damsel, vampy villain, or other stereotypes.

Like Hayakawa, Wong continued to work well into the era of the talkies, though she rarely got a leading role and also reportedly lost out in a part in 1937's "The Good Earth," even though it was set in China. According to "Perpetually Cool: The Many Lives of Anna May Wong," the role (and, eventually, an Oscar) instead went to Luise Ranier in yellowface makeup.

LGBTQ stars faced serious homophobia

Queer people in Hollywood faced a difficult choice: Live openly, but potentially lose their career, or stay closeted and keep acting. Some were able to balance both for a time, like actor William Haines, who lived openly with his partner until his career wound down and he became a successful interior designer (via Slate). Others kept their personal lives on intense lockdown. According to the Los Angeles Public Library, famous drag performer Julian Eltinge made some silent films based on his popular stage acts, but was cagey about his private life. He also engaged in performatively stereotypical male behavior like smoking, drinking, and getting engaged (but never married) to multiple women.

Women were hardly exempt from the homophobia of silent-era Hollywood. According to Diana McLellan's "The Girls: Sappho Goes to Hollywood" (via The New York Times), Greta Garbo and Marlene Dietrich carried on an affair that both would deny to their dying days. Others saw that their sexuality remained a stumbling block, no matter how secretive they were. As per The New York Times, in 1919 actress Jean Acker found herself in a lavender marriage with Rudolph Valentino, meant to obscure her sexuality. The pair soon divorced, but after his second marriage ended in a similar fashion, speculation soon turned to Valentino himself (via Fuse).

Actresses dealt with exploitation and abuse

With so much sexual licentiousness running rampant in Hollywood, some actresses hoping to break into the movies were presented with an unseemly proposition. As a 1920 article in Photoplay described it, rumors swirled that aspiring stars had to disappear into a backroom with some powerful executive or producer to get a key contract. The article ultimately deemed the accusations to be largely unfounded. Yet, with modern casting couch rumors still a part of the entertainment industry, it's hard to dismiss the older stories of silent film stars like Louise Brooks, who claimed to see one woman get a contract at MGM after an assignation with a higher-up (via The Guardian). There was even a stag film titled "The Casting Couch" released in 1924, which showed just such a situation (via Silent Era).

However, it wouldn't be fair to pretend that all women in Hollywood were helpless waifs thrown at the feet of slavering predators. As Naomi McDougall Jones reports in "The Wrong Kind of Women" (via The Atlantic), the silent film era actually held room for many female creators, including not just actresses, but writers, directors, and producers. It was only during the transition to talkies and with increased financing that many women were forced out of positions of power in Hollywood.

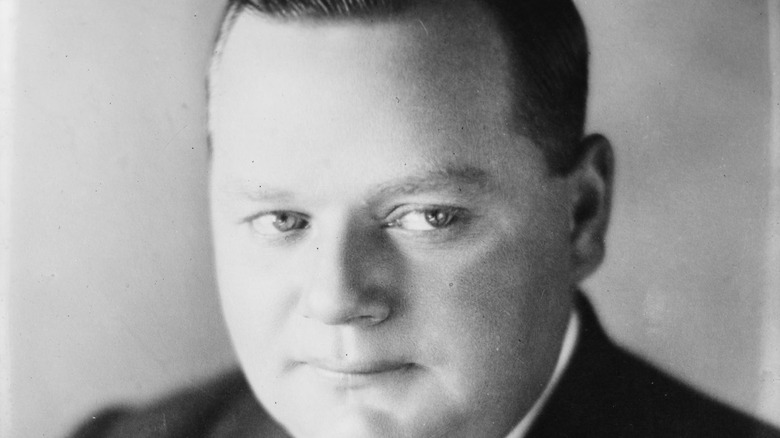

Silent film stars weren't immune to scandal

Roscoe "Fatty" Arbuckle used to be a big deal. As reported in The New Yorker, he was a stupendously successful film comedian who loved to party. But one 1921 get-together at San Francisco's St. Francis Hotel would prove to be his undoing. The details of what happened became increasingly tangled, but the outline centered on a young actress named Virginia Rappe. At the party, Rappe went to use the bathroom in Arbuckle's room. He eventually followed her and locked the door. Later, other partygoers found Rappe in distress, grappling with intense abdominal pain. A doctor said that she'd simply drank too much and prescribed morphine. When she didn't get better, Rappe was transferred to a medical facility where she died on September 9 of peritonitis and a ruptured bladder.

Some guests maintained that Arbuckle had sexually assaulted Rappe, perhaps causing her injury due to his considerable bulk. Arbuckle claimed that he had found Rappe in distress and attempted to help her. Either way, the press went wild, with some calling him a "beast" and others proclaiming his innocence.

Though Arbuckle was acquitted in the case surrounding the tragic death of Virginia Rappe, studios turned their backs on him and theaters banned his movies. His acting career fizzled, though he made a modest comeback as a director. He was poised to return to acting when he died of a heart attack in 1933. Whether or not he would have made a triumphant return, Arbuckle's reputation was forever linked to the death of Virginia Rappe.

Murder wasn't off the table

Silent stars could be hit with drug addiction, systematic abuse, and scandals that tanked their dreams. But that wasn't necessarily the worst thing that could happen to someone trying to make their way in Hollywood. For a very unfortunate few, the glittering world of film brought them straight to the ends of their lives.

Though Hollywood made many moviegoers and hopeful actors go starry-eyed, the glamor on screen didn't win everyone over. Literary magazine The Smart Set certainly wasn't impressed in September 1922, when George Jean Nathan and H.L. Mencken wrote that, compared to the truly glamorous world of the stage, film sets were basically the moral equivalent of hog wallows.

That sense of tawdry violence could be summed up by an actual murder that remains unsolved to this day. According to History, director William Desmond Taylor was found dead in his bungalow in Los Angeles. The cause of death was a gunshot wound to the back. He'd clearly been murdered, but by whom and why was never made clear, though some actors were linked to his demise. Taylor had apparently been involved in a romance with a teenager, to the great (and perhaps murderous) disapproval of her mother.

Some actors didn't make it to the talkies

There's a popular idea that many silent film actors didn't transition to the talkies because their voices were unfit to record. The 1952 musical comedy "Singin' in the Rain" hinges on this, as fictional actress Lina Lamont struggles to drop her thick Brooklyn accent. But was this really the case? Movies Silently points out that many actors made the transition to sound just fine, though some experienced a few speed bumps along the way, like actress Marion Davies because of her stutter (via The Stuttering Foundation).

While the schadenfreude-infused image of silent film greats stumbling over something as simple as talking may have been overstated, a few stars really did hit a wall when presented with a microphone. As Laura Petersen Balogh writes in "Karl Dane: A Biography and Filmography," actor Karl Dane's career did begin a downturn as talkies rose, though his thick Danish accent was only part of the problem.

Perhaps the poor reputation of silent film star voices also had something to do with the movie studios. As former child star Diana Serra Cary told The Guardian, film executives talked trash about silent films to make it seem as if the more expensive and complicated sound movies were worth all the effort. Some old stars, herself included, saw their lights fade as a result.