Brutal Facts About Amputation Throughout History

Amputations were often the only lifesaving surgery possible in the ancient past and the most common (and often only) form of treatment available for the presence of advanced infection, dead flesh, and broken bones until the past couple of centuries. During wartime, amputation was often the easiest and fastest way to save a person's life (per The American Battlefield Trust).

Ancient amputations were crude and the chances of surviving one weren't very good. Major advancements came in the 16th century when French surgeon Ambroise Paré invented a technique to ligate blood vessels to replace the old brutal system of cauterizing wounds, according to a study published in Clinical Orthopedics and Related Research. In the 18th century, professor Jean Petit introduced another life-changing innovation: a better tourniquet so patients wouldn't bleed to death during the amputation. Other than that, amputations continued to be quite terrible, painful medical procedures for a very long time.

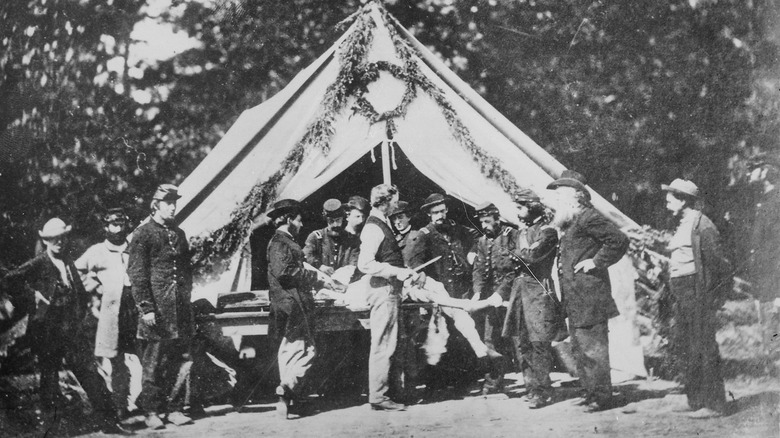

Things significantly changed in the second half of the 19th century. While the Civil War saw an astonishing number of amputations, it also marked a defining point in amputation surgery, especially towards the end of the war. New innovations that helped the situation were ambulances that helped transport the injured, improved methods of tying off blood vessels to stop patients from bleeding out, and using anesthetics so patients felt less pain during procedures, as reported by Baylor University Medical Center Proceedings.

Amputations go back thousands of years to ancient times

It's hard to imagine prehistoric societies conducting surgeries and amputations, but recovered ancient bones tell us they did. They likely weren't frequent and the chances of surviving were probably very low, but archeologists have proof that our ancestors were already performing quite advanced surgical procedures thousands of years ago.

The oldest of those surgeries was an amputation that occurred over 30,000 years ago in Borneo, according to a 2022 study published in Nature. The bone remains, found inside a cave, belonged to a young adult of around 19 or 20 years of age. After close inspection, researchers realized the skeleton was missing the lower third of the leg, which had been amputated using a clean cut. Because of the obvious healing of the bone, scientists also estimate the amputation had occurred at least six years before death, during childhood.

Before this finding, the oldest amputation on record was "just" 7,000 years old and belonged to a Neolithic male found in France, according to a 2007 report published in Nature. Here too, scientists suspected a surgical amputation of the lower leg many years before death. In the book "The Rehabilitation of the Amputee," Dr. Lawrence W. Friedmann looks at amputations in ancient cultures, including ancient Peruvian civilizations, the Inuit people, and the Dama tribe in Africa — all of which seem to have performed amputations in an effort to save somebody's life.

In ancient times, amputation was sometimes punitive

Not all amputations in ancient history were done for medical reasons. Limb amputation has been carried out through the ages as a punitive method in various parts of the world. Some of the oldest records of this go back to Babylonian times when offenses were often punished with amputation and to Peru, where surprisingly mild offenses like theft, lying, and laziness were punished with amputations as well, according to a 2014 study published in the Clinical Orthopedics and Related Research.

The Romans started practicing punitive amputation during the time of emperor Constantius Flavius Valerius Aurelius, though it was mostly reserved to punish slaves. By the time emperor Phocas took over power, things were starting to get more and more gruesome, and Phocas added to that by introducing torture, blindness, and amputation as punishment for many crimes (via the Clinical Orthopedics and Related Research journal).

Punitive amputation was rarely used after the Renaissance but it was again introduced during the 1800s, as Europeans embarked on the colonization of Africa. According to a 2016 report published in the Sociological Association, Belgian colonizers were known to cut the hands of Congolese slaves who were not processing rubber at the speed they demanded. Punitive amputation is still practiced in countries like Iran and Afghanistan. In July 2022, Amnesty International condemned the decision of an Iranian court to punish two men convicted of stealing by cutting off their fingers.

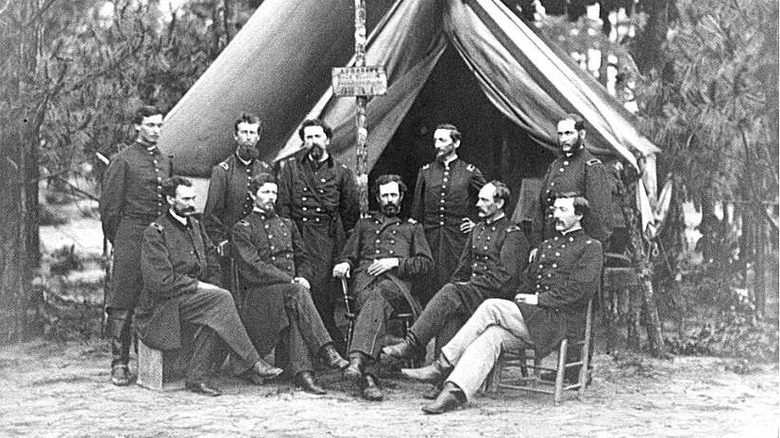

Three out of four surgeries during the Civil War were amputations

Although there are basic records of war casualties going back several centuries, detailed medical record-keeping was born during the Civil War, as reported via Northwestern University's Galter Health Sciences Library & Learning Center. According to an article published in The Journal of Military History, the notion of counting the dead so every life lost could be identified was also born at this time. Because of this, we now have access to very detailed (and often gruesome) information on injuries and treatment of soldiers during one of the bloodiest wars fought on American soil — and this includes a rather accurate number regarding amputations during the war.

The American Battlefield Trust estimates that 75% of surgeries that took place during the Civil War were amputations, averaging about 1,250 a month. With so many injured soldiers needing care, speed was essential. Doctors didn't have a lot of time or resources to look for alternative options, and amputation was the treatment of choice for infections, broken bones, torn nerves or muscles, and most other major injuries of the limbs. Once you were seriously injured, your chances of walking away without amputation were very low.

Civil War amputations were so common, it resulted in piles of discarded limbs

In 2018, scientists digging in a well-known battlefield in Virginia uncovered what turned out to be a major first: a mass grave for limbs. For decades, researchers had known that discarded limbs after amputation were a major issue in field hospitals during the Civil War, but this was the first proof of what happened to them: They ended up in mass graves in fields (via NPR).

Based on the previous estimate from the American Battlefield Trust of about 60,000 amputations during the Civil War — and assuming each soldier only lost one limb — that left medical personnel with a lot of discarded body parts that needed to be disposed of.

In his book "The Wound Dresser," poet Walt Whitman describes visiting camp hospitals in the Potomac in 1862 and noticing the discarded limbs. "Outdoors, at the foot of a tree, within ten yards of the front of the house, I notice a heap of amputated feet, legs, arms, hands, etc. — about a load for a one-horse cart," Whitman wrote. While there are no records of what exactly happened to all those limbs, the 2018 discovery is an example of what historians have long suspected: Amputated limbs were either buried or potentially burned (via the American Battlefield Trust).

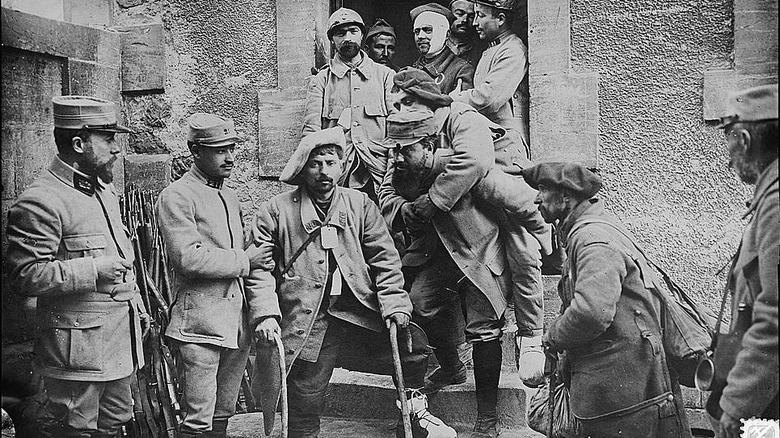

Improved weapons during WWI led to even more gruesome wounds and amputations

Amputation continued to be a very common surgery during World War I. According to the book "Dismembering the Male: Men's Bodies, Britain and the Great War" by Joanna Bourke (via Études Lawrenciennes), 41,000 British soldiers had limbs amputated during the war, with 3% losing more than one limb. Compared to the Civil War and other older conflicts, armies battling in WWI had much more modern weaponry: explosives with shrapnel balls, high-velocity cartridges, and fast machine guns. They were effective fighting weapons that caused a lot of damage to bones and often required surgery as the only way to save a patient (via Encyclopedia).

WWI also saw the appearance of a new reason for amputations: trench foot. Caused by standing in water for long periods of time (common for soldiers hiding in trenches), trench foot causes intense pain, numbness, and swelling, according to a report in Wilderness & Environmental Medicine. The problem became so severe that over 75,000 British soldiers died from it during WWI alone. While doctors tried prevention tools and traditional therapies to deal with it, amputation was still used when there was no other option.

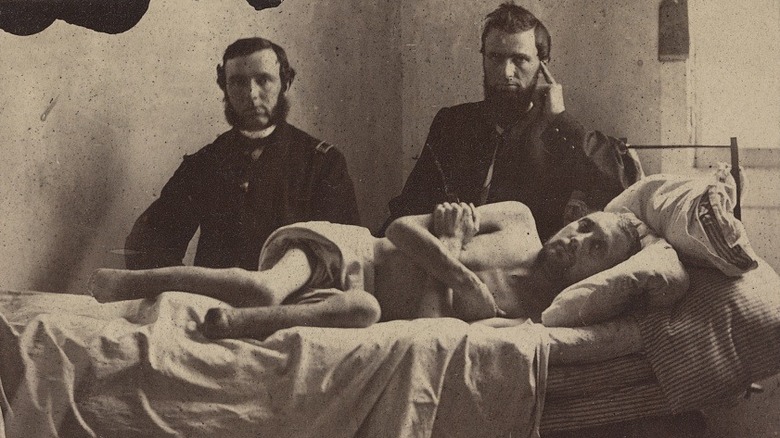

Infections killed a large number of amputees in the 19th century

Not only were there no antibiotics during the Civil War, but there was also no understanding of germ theory and the importance of using sterile techniques during the care of wounded Civil War soldiers (via The American Biology Teacher). Because of a lack of understanding of how diseases spread and what causes bacteria to grow, doctors didn't wash their hands or disinfect medical instruments between patients.

In a 1918 report published in The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, former Civil War surgeon W.W. Keen looks back at conditions in war hospitals in 1861: "We operated in old blood-stained and often pus-stained coats ... We used undisinfected instruments from undisinfected plush-lined cases, and still worse, used marine sponges which had been used in prior pus cases and had been only washed in tap water."

He describes Civil War hospitals as having "no sterilized gauze dressing, no gauze sponges" and often dressing wounds using anything from shirts to tablecloths when operating in makeshift hospitals. By his own estimations, "amputations averaged over 50 percent mortality" because of these conditions. By WWI, things had improved significantly regarding disinfection — so much, in fact, that Keen was able to point out that the "victory over infection is the reason for the greatly diminished number of amputations in the present war. Moreover, the mortality of amputations in our armies is low."

Painkillers were scarce and often deadly

While there were effective painkillers available at the time of the Civil War, access to them wasn't always straightforward. This was a particularly big problem in the South because the Union Navy blockade prevented medicines from being imported, according to a study published in Scientific Reports. And while anesthesia meant amputations were usually painless, a lack of painkillers resulted in a lot of suffering once soldiers woke up after surgery.

According to "A Manual of Military Surgery: Prepared for the Use of the Confederate States Army" (via Harvey Cushing/John Hay Whitney Medical Library), Civil War doctors were encouraged to use opiates to treat pain on the battlefield — not only to treat post-amputation pain but also to treat pain from illness or other injuries. And while today we have synthetic opioids available that can be better dosed, doctors at the time had access to painkillers in the form of laudanum (a tincture produced by dissolving opium in alcohol), opium pills, and later on, injections of morphine.

When they did have access to opiates, Civil Wars doctors used them a lot. So much, in fact, that this led to America's first opioid crisis. After becoming addicted during the war, many veterans continue taking opioids (and especially using the more accessible morphine injections) long after their time on the battlefield had finished (via History).

Sedating patients before anesthetics didn't always work

The first-ever surgery performed under anesthesia dates back to 1846, and it was performed by a dentist in Boston, according to the Journal of Investigative Surgery. This was a major breakthrough in the surgery field. According to University of Alabama at Birmingham professor Dr. Maurice S. Albin, chloroform was first used just a year later. But it wasn't until the start of the Civil War that these agents were first used on a massive scale. Albin believes (via Newswire) the "firsthand exposure to anesthetic agents and techniques, as well as to their side effects and complications" that Civil War doctors experienced forever change the history of anesthesia.

So what happened before ether and chloroform came into play? "Prior to the war, alcoholic drinks, physical restraints, opioid drugs and bite blocks were the most typically employed methods of keeping a patient under control during surgery," Albin explains. Long before that, ancient civilizations used the mandrake plant to somewhat sedate patients, while the Romans and late Medieval English surgeons sometimes used a special mix known as "dwale." Although dwale's recipe varied, it usually consisted of a mix of alcohol and a number of strong ingredients like hemlock, bryony or mandrake, opium, and henbane — a dangerous and not always effective mix, according to a report published in BMJ.

Amputations have often led to death throughout history

Historically, amputations have always carried a high level of mortality, whether they were performed on the battlefield or in hospitals. A study published in the Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine showed that even amputations done at the prestigious London Hospital in the 1850s still carried a mortality rate of 46%. Lower limb amputations had a particularly poor prognosis, with around 70% of patients dying as a result of the procedure.

Things were significantly different during a war when decisions had to be made quickly and conditions were less than ideal. Still, things improved quickly over just a few years. According to "Civil War Medicine: Challenges and Triumphs" by AJ Bollet (via Proceedings Baylor University. Medical Center), the British Army saw 100% mortality for hip amputations and 26% for arm amputations during the Crimean War across just two years, while Civil War amputations less than a decade later resulted in mortality rates of 66% and 14% for the same surgeries.

For centuries, the main reason for death after amputation was infection and gangrene. It wasn't until later during the Civil War that doctors realized mortality was lower if they amputated quickly after injury. For example, mortality for amputation of a leg at the thigh level was 38% if done within 48 hours of injury, but the numbers went up to 73% mortality after 48 hours.

Many battlefield amputations were carried out by doctors who had zero experience with surgery

Medical school and training in the 1800s were nothing like they are today and becoming a doctor at the time required just 32 weeks of schooling spread across two years, followed by three years of guided practice called preceptorship. Lessons included pathology, botany, and anatomy. During the 19th century, students didn't actually participate in things like dissection or actual anatomy practice. Instead, they would attend a lecture where a professor will conduct the actual dissection and the students would just observe, as reported in the Journal of Evidence-Based Integrative Medicine.

Because of poor refrigeration systems, some schools couldn't access bodies all the time, which meant that many medical schools did not require anatomy laboratories to graduate or only had observation classes when possible. This also impacted surgery practice. Less than 1% of graduating students had performed any kind of surgery during their time at school. When bodies were available, students could observe surgeries performed by doctors, but even then, the surgeries were usually minor things like bloodletting. This meant a lot of what doctors knew was learned through years of practice after graduation.

But the Civil War seemed to inspire more people to become doctors. According to Baylor University Medical Center Proceedings, there were only 113 army doctors before the war but the number had grown to 15,000 by the war's end. Many of those doctors were using the battlefield as their learning ground.

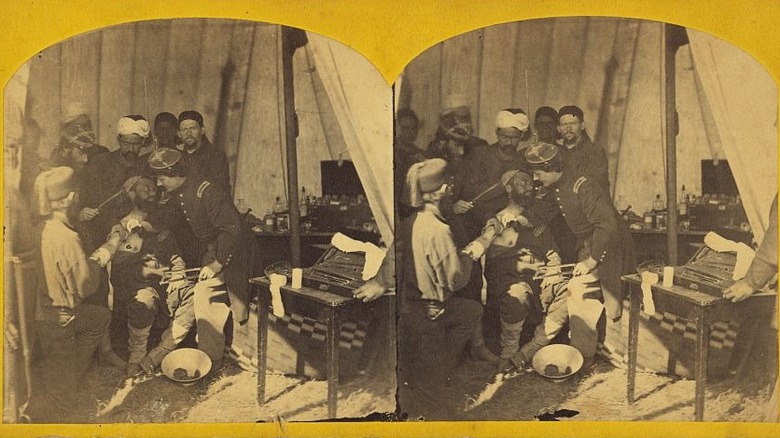

The tools used for amputation were brutal

During the Civil War and later armed conflicts, all doctors had access to surgery and amputation kits. The contents varied depending on what was accessible at the time, but a typical Civil War amputation kit would at least contain a catheter, a tourniquet, a bone saw, amputation knives, and dressing forceps (via National Archives).

As detailed by American Battlefield Trust, patients would first receive an anesthetic in the form of chloroform or ether while waiting for the surgery. To amputate a limb, a surgeon would first tie up the tourniquet around the limb to slow down bleeding, then cut through skin and muscle with the smaller knives before using a saw to get through the bone. Doctors then had to tie off the cut arteries to prevent the patient from bleeding out (depending on what was available, things like thread or even horsehair could be used), and the stump was bandaged. Luckily for patients, although the procedure was surely painful and brutal, at least the surgeries lasted no more than 10 minutes (per the National Museum of Civil War Medicine).

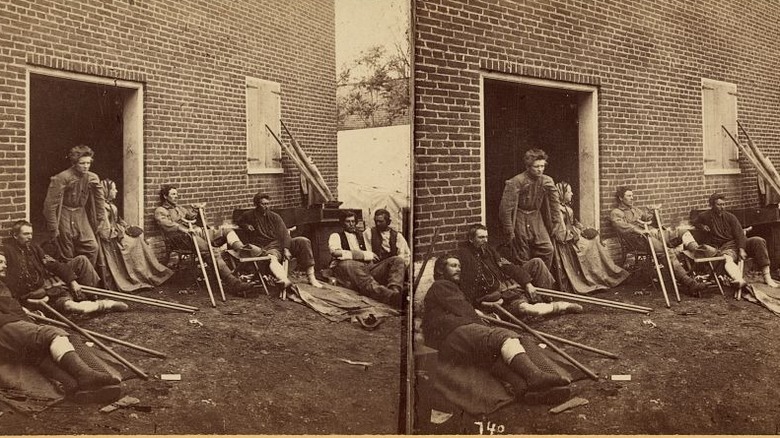

After amputation, survivors had to deal with terrible prosthetics

Historically, the horror of primitive amputation didn't end with the war. Amputees returned home unable to work, often in pain or addicted to painkillers, and with very few options for the future (per History). Though prosthetics were available at the time, they were primitive — legs had to be strapped on and prosthetic arms often ended in a hook rather than a fingered hand, according to The National Museum of Civil War Medicine. While Congress dedicated a significant amount of money to provide Union soldiers with the best artificial limbs available at the time (per U.S. Department of Veteran Affairs), Confederate soldiers did not qualify for help as they had fought against the country.

Ironically, it was an amputee Confederate soldier that had the biggest impact on the future of prosthetics. As detailed by American Battlefield Trust, James E. Hanger was just 18 years old when he was hit by a cannonball and his leg was seriously injured. A Union surgeon amputated the leg close to the hip and Hanger's case was one of the first documented cases of amputation in the war. After returning home, Hanger struggled with pain and day-to-day difficulties because of the precarious artificial limb he had been given, so the young ex-soldier designed his own version using rubber bumpers and oak barrel staves. He eventually received a patent for it and developed his own business producing prosthetics.