Riothamus: The Ancient King That May Be The Real-Life King Arthur

One of the most famous British legendary figures is King Arthur. His story, with all of its elements like the castle of Camelot and the Knights of the Round Table, has appeared in a variety of movies and TV shows (via IMDB), from magical adventure stories like BBC's Merlin to farce comedies like Monty Python and the Holy Grail. These all contain fragments of the centuries-old story but, as Britannica explains, historians still cannot confirm whether King Arthur ever actually existed.

The idea that King Arthur may have been real is a somewhat contentious one among modern historians. The book, "King Arthur: The Making of the Legend," explains this in no uncertain terms, emphasizing how academics tend to regard him in much the same way as characters like Sherlock Holmes: an important part of British culture, but likely little more than a work of fiction. However, this does not change the fact that numerous scholars have tried to research whether the story may yet contain a grain of truth.

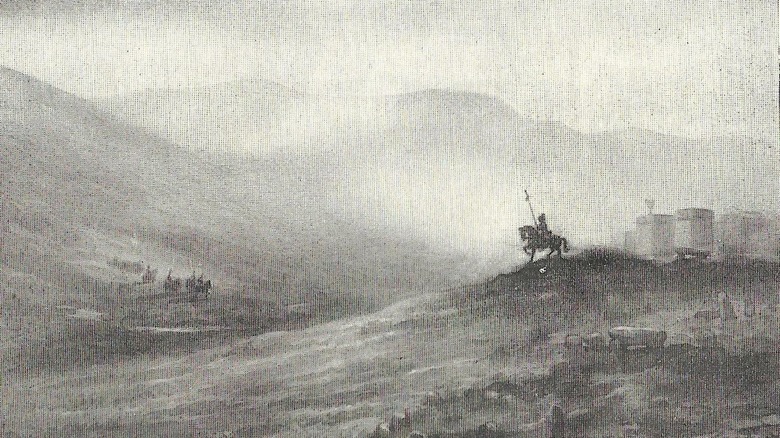

The chance that a famous legendary character like King Arthur could have originated in stories from the real world is a tantalizing one, and there's one mysterious figure in Medieval history whose true story may just be the basis for Britain's most famous mythical king. The New York Times lays out the case for a British ruler from the fifth century, known only as Riothamus, whose reality may have eventually grown into a legend.

When history and legend intermingle

The story of King Arthur became popularized in the 12th century when Geoffrey of Monmouth wrote the book "Historia Regum Brittaniae." It purports to be an accurate account of Britain leaders and was considered to be a historical fact for centuries. Eventually though, as Barnes & Noble highlights, it was later found to be only loosely based on reality. Described as "wildly inaccurate," much of Monmouth's stories are now considered to be little more than fiction. However, the story of King Arthur was one of the most popular in the book and was later popularized by author Thomas Malory, who wrote a dramatized account, "Le Mort D'Arthur," in the 15th century.

Monmouth's stories weren't the origin of King Arthur, however. Britannica mentions that the story likely originated in Celtic-speaking parts of Britain, like Wales, and there were earlier written accounts of him too. The "Historia Brittonum," a ninth-century historical record by Nennius, mentions a magnanimous leader named Arthur, who defended his people from the invading Saxons during the sixth century. Unfortunately, Nennius' sources are a little unclear, and with good reason. This story comes from the era known as the Dark Ages. Smithsonian Magazine explains that Britain, at the time, was in a destitute state. Following the Romans' withdrawal from the island, society had largely collapsed and illiteracy was widespread. It was this fractured land, ruled over by tyrannical kings, in which the legends of a hero named Arthur first arose.

Riothamus, the high king

Riothamus is not actually a name. Instead, it's a title, which The New York Times explains means "high king." His true name, seemingly, has been lost to history, but an illustrious title like this certainly implies he carried great respect. The book, "The Historic King Arthur: Authenticating the Celtic Hero of Post-Roman Britain," notes that it's not unusual for Medieval rulers to go by title more often than not. A much more famous example is Genghis Khan, who was seldom known by his actual name, Temujin. Whatever his real name though, scholars have noted some similarities between the few surviving records of Riothamus and the legendary tales of King Arthur.

Perhaps the biggest similarity is that King Arthur famously crossed the sea to wage a military campaign in what is now modern-day France. At the time, it was known as Gaul and, according to Time, historical records show that Riothamus truly did once do this. This is a particularly promising detail because leading such a gallic campaign is part of the earliest stories about King Arthur, predating the dramatic embellishments which would appear in later retellings of the tale. During such a brutal and war-torn time in British history, the story of a heroic figure would have doubtless been of great significance to the common people, explaining the popularity of Arthur in folklore. It's impossible to tell if Riothamus truly was Arthur, but some of the evidence is quite compelling.

The records of Jordanes

The fifth century was a turbulent time in Europe, with the established world order falling apart as once-great nations were besieged by armies challenging their power. The greatest presence at the time was still the Roman Empire but, as World History Encyclopedia explains, Rome wasn't doing so well. Defending against the rising threat of the Visigoths was Rome's top priority at the time — the same Visigoths who would eventually take over the city of Rome itself and bring the Western Roman Empire to its knees. To fight off the Visigoths, Rome abandoned Britain, drawing its forces back toward the South. Smithsonian Magazine describes how the sudden withdrawal of the Romans caused Britain to fall apart practically overnight. The economy collapsed, infrastructure vanished, and bloody conflicts arose with Saxon invaders.

During a particularly dire time, Rome even called upon the Britons to come to their aid, as recorded by a sixth-century Gothic historian by the name of Jordanus. In his work, "The origin and deeds of the goths," he describes how the Roman Emperor Anthemius sought to repel an army of invading Goths from Gaul, calling for help from a Briton King, Riothamus, who was clearly still loyal to Rome. Before he could meet up with the Romans though, Riothamus' army was intercepted by the Goths and hopelessly outnumbered.

King Arthur's campaign in Gaul

Arthur's voyage to Gaul is a prominent part of his story in the "Historia Regum Brittaniaea," in which it's cast in a valiant and heroic light. In the legend, Arthur is a nigh-invincible figure, and Monmouth's writings talk about how his armies "began to lay waste that country on all sides." Riothamus' actual story, however, was far less successful. In "The origin and deeds of the goths," Jordanes describes how Riothamus faced an army of Visigoths so large, he calls it "innumerable." Impressively, Jordanes mentions how it was a long fight, suggesting Riothamus' forces put up a strong defense. Seemingly though, it was to no avail. Riothamus suffered a crushing defeat, losing a large part of his army and being forced to retreat to Burgundy. This was all part of an ongoing war in which the Burgundians, like Riothamus himself, were loyal to Rome. Rome would ultimately lose, however, and Emperor Anthemius himself was killed soon afterward.

Despite the big difference in how their battles were fought, the stories of Arthur and Riothamus are still quite similar, as The New York Times notes. After all, it makes sense for the stories told afterward to make him more heroic. The most noteworthy part, however, is simply the fact that the battle happened at all. The gallic campaign of King Arthur is a defining part of his earlier stories, and Riothamus is seemingly the only British ruler on record to have done the same thing.

The betrayal of Arthur

In the story from the "Historia Regum Brittaniaea," King Arthur's story draws to a close after he's betrayed by the knight Mordred, leading to a bitter fight between the two. It's notable though, that this part of the tale isn't included in all versions. The Camelot Project mentions how traditional Welsh versions of the story don't make any mention of Mordred's treacherous actions. Nonetheless, this betrayal later became an important part of Arthurian legends, and as The New York Times notes, Riothamus also suffered a betrayal that seemingly sealed his fate.

A fifth-century Roman civil servant by the name of Sidonius Apollinaris left behind a collection of letters, and one appears to detail how Riothamus was betrayed. A paragraph in Apollinaris' letter (via Perseus digital library) mentions how a man named Arvandi had sent word to the king of the Goths, giving away the location of the Britons and advising that they be attacked, perhaps as a way to win favor with the formidable Goth army. There don't seem to be any surviving historical records of what happened to Riothamus after this, but it's not difficult to imagine this betrayal likely caused his undoing, in much the same way that Mordred caused the downfall of King Arthur.

Riothamus and Sidonius Apollinaris

Sidonius Apollinaris is seemingly the only source for Riothamus' betrayal, but he's also likely to be a reliable one. Apparently, he and Riothamus were friends while Riothamus had been in Brittany. One of Apollinaris' letters is even titled "To his friend Riothamus." The letter speaks about how the Bretons had been enticing Roman slaves away from their masters to live in Brittany and, with Rome being so preoccupied, it's unlikely they'd have been able to enforce their laws so far North. Apollinaris' letter doesn't mention what exactly became of the slaves and whether they were drafted to fight in Riothamus' army or simply left free to live their lives.

At the time, according to "The New Arthurian Encyclopedia," Riothamus was stationed somewhere North of the Loire, together with around 12,000 troops. Seemingly, the entire army had crossed the sea into Gaul. Some historians debate how much power Riothamus actually had and the extent of his territories, but commanding this many soldiers suggests he must've been a noteworthy and inspiring leader. For comparison, historian James Grout notes that in the first century, a Roman legion contained between 5,000 and 6,000 soldiers. While a few historians have dismissed Riothamus as a minor leader, no doubt because of the lack of records about him, others point out that his title alone marks him as a formidable opponent. Leading two legions of troops certainly seems to confirm that.

The Isle of Avalon

History has no record of the eventual fate of Riothamus. According to The New York Times, the trail goes cold after A.D. 470, with no more surviving records of what happened after he'd been forced to retreat to Burgundy. The tales of the "Historia Regum Brittaniaea" say that after his final battle, King Arthur was badly wounded and was carried to the Isle of Avalon, where his story ends. Like much in the stories, the details of Avalon are a mystery, but Britannica mentions that it's been popularly linked with the town of Glastonbury in Southwest England.

It's noteworthy, however, that there's a town in Burgundy called Avallon. "The Discovery of King Arthur" points this out, noting that Avallon is a Gaulish name, and suggesting that this place in Burgundy may have been the final resting place of Riothamus. It's also worth noting that the word "isle" in the name need not refer to a literal island, as with the Île de France region of modern-day France, which surrounds Paris. There's just one inconvenient problem with this idea. No historical records exist to show that Riothamus ever set foot in the town of Avallon. No version of the name is even mentioned by any known writer older than Geoffrey of Monmouth in the 12th century. Without any conclusive proof or reliable ancient records, some scholars are understandably skeptical that this is truly the Avalon of Arthurian legend, even though it seems quite a coincidence.

Arthur's birthplace

"The New Arthurian Encyclopedia" mentions that Riothamus was likely the commander of some territories in Southwest Britain before he left for his ill-fated campaign in Gaul. By coincidence, the King Arthur of legend also has some intimate ties with this part of the world, which also strengthens the idea of Riothamus being the origin of King Arthur's stories. In Cornwall, in the Southwest corner of modern-day England, are the ruins of Tintagel Castle. The castle itself only dates back to the 13th century, but Tintagel is an ancient place that archeologists believe had a thriving community in the 5th century CE. It was also, according to Geoffrey of Monmouth, the birthplace of King Arthur — a fact which locals are quite proud of, and which the castle makes certain to mention to any visitors.

Its location on the coast allowed ancient Tintagel to trade actively with the Mediterranean, allowing it to grow into a prosperous place in fifth-century Britain. At the time, this made it stand out significantly from the rest of the ruined island. Per Smithsonian Magazine, the people of Tintagel lived well in comfortable houses, even as the rest of Britain was collapsing in on itself. A place of abundance like this would've been an auspicious place to be born, and the ruler of Tintagel at the time would've likely held considerable power and respect in the surrounding area. Had this been Riothamus' home, it's no wonder he was able to gather such a large army.

The castle of Camelot

Almost synonymous with Arthur in the stories is Camelot, the famous castle from which Arthur ruled his kingdom. In the fifth century, however, castles would've been unlike the romanticized image we now have of them. As English Heritage explains, the first true castles wouldn't be built for another few centuries, meaning that Camelot would've been not a castle but a hill fort. One ancient hill fort proposed as a candidate is Cadbury Castle in Southwest Britain. Visit Somerset explains that the site was in use for over 4,000 years and, even though it was destroyed by the Roman army around A.D. 70, it had been rebuilt again by the end of the fifth century. Compellingly, the fort also used to be called Camalet (via Somerset Military Museum).

Archaeologists have considered Cadbury Castle such a compelling candidate that they studied the site extensively in the 20th century, publishing their findings in the book "Was this Camelot? Excavations at Cadbury Castle, 1966-1970." They found that it was likely home to a wealthy community around the late fifth century, with remains of "Tintagel-type pottery" being found in the ruins. Coincidentally, the site was refortified by its new owners around A.D. 470.

Cadbury Castle, however, is far from the only possible location of Camelot. Over the years, a few others have been suggested, and the latest proposal came as recently as 2016 (via Science Alert). Much like Arthur himself, the truth about Camelot is still an open question among historians.

The true King Arthur?

King Arthur is one of the most famous figures in British legend, and thanks to Geoffrey of Monmouth's "Historia Regum Brittaniaea," King Arthur's history was considered a genuine part of British history for centuries. Perhaps this is why scholars have found him such a compelling figure, and why so many people have worked so hard to try and find out if the Arthur of legend truly was based on a historical figure. According to World History Encyclopedia, Riothamus isn't the only contender for Arthur's metaphorical crown. Other academics have proposed a Roman officer Lucius Artorius Castus, a Welsh folk hero named Caradoc Vreichvras, and the Saxon King Cerdic, among many others.

The origin of King Arthur's legend may originate with any of these historical figures. Or King Arthur's stories may have been influenced by more than one of them, being told as an amalgamation of heroic deeds by famous rulers. Alternatively, the stories could come from somewhere else entirely or even be a work of pure fiction — inspiring stories to tell over ale, providing escapism to people living difficult lives. To date, as Britannica notes, there's no solid historical evidence that King Arthur was a real person. After the passing of so many centuries, there's a chance there never will be. But then, perhaps the reality doesn't really matter. After all, the most important thing King Arthur ever did was to inspire the people who heard his stories. In the end, a good story is immortal.