The Kurdish Genocide Explained

Although the genocide against the Kurdish people in Iraq technically lasted less than one year, the devastation it wreaked on the Kurdish community was unfathomable. Known as the Anfal campaign by the Iraqi government, the name of the campaign was taken from the eighth chapter of the Quran, which refers to "the spoils of war" and reflected the thousands of Kurdish villages that became subject to looting. The use of religious language also came from the fact that President Saddam Hussein tried to portray Kurdish people as heretics.

Over the course of eight stages, the genocidal Anfal campaign sought to liquidate the Kurdish population in Iraq. The Anfal campaign was especially horrific in its use of chemical weapons, leaving many of its survivors with lifelong health problems. And although the Iraqi government denied that any deaths were the result of the war being fought, the Anfal campaign was in fact planned genocide that was executed while the rest of the world watched and said nothing.

Although some of the top perpetrators of the genocide were taken to court, as of 2023 many of the perpetrators and collaborators still have not been held accountable. And despite the fact that the Iraqi court found that government should compensate the victims of the genocide, there have yet to be any reparations made. This is the Kurdish genocide explained.

Kurdish people in Iraq

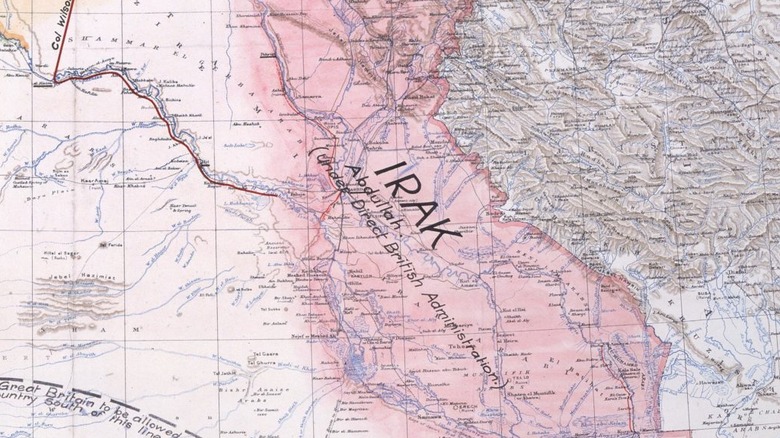

After the British Empire took over the colonization of what is now considered to be Iraq in 1918, the Kurdish people in the region were absorbed into British-controlled Iraq. Under the Arab nationalist puppet regime installed by the British, Kurdish people as well as Assyrians and other ethnic minorities were oppressed. Although there were frequent uprisings, they were violently suppressed, even after Iraq's independence, according to "Modern Genocide," edited by Paul R. Bartrop and Steven L. Jacobs.

Middle East Quarterly writes that despite this, Kurdish nationalists continued to push back against the Iraqi regime. After the Second World War, Mullah Mustafa Barzani became the leader of the Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP) and led the revolt against Iraq in both the First and the Second Iraqi-Kurdish Wars, which sought to establish an autonomous Kurdish administration in Iraq.

Following the First Iraqi-Kurdish War, the Ba'ath regime agreed to recognize a Kurdish nation in 1970. However, this autonomous region was to still be under Iraqi authority and in 1974, Barzani once more led Kurdish people to revolt, becoming known as the Second Iraqi-Kurdish War. Although Iran offered support to the Kurdish people during the Second War, their support ended after the Algiers Agreement was made, according to History. As a result, the Kurdish rebellion was subsequently soon suppressed by Iraqi troops. One year after the Second Iraqi-Kurdish War ended, thousands of Kurdish people were forcibly displaced by the Iraqi government and put into camps while over 2,000 Kurdish villages were destroyed.

The Iraq-Iran War

In 1975, Iraq and Iran signed the Algiers Agreement following the Second Iraqi–Kurdish War, which established the border between Iraq and Iran using the Shatt al Arab River. But after Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi of Iran was overthrown, Iraqi President Saddam Hussein took advantage of the situation and launched an invasion into Iran, Alexander Mikaberidze writes in "Conflict and Conquest in the Islamic World."

The Iran-Iraq War started on September 22, 1980, when Iraq launched airstrikes and a ground invasion into Iran. Iraq invaded Iran's western Khuzestan Province through Iraqi Kurdistan, according to ThoughtCo., both in order to reclaim territory and because President Hussein believed that the Arab population in Khuzestan would support the invasion. Not only did the Arab people of the Khuzestan Province flee instead of joining the Iraqi invasion, but the Iranian army was able to mobilize sooner than President Hussein had anticipated and were able to repel the invasion. As a result, what was expected to be a quick invasion became a drawn-out war that would last eight long years, according to "The Kurdish Struggle, 1920-94" by E. O'Ballance.

Ultimately, despite resulting in up to 1.5 million deaths (per The Guardian), the Iran-Iraq War ended in a stalemate on August 20, 1988, through a ceasefire brokered by the United Nations. But during the final year of the war, the Iraqi government focused their attention on the Iraqi Kurdish population and unleashed a genocidal campaign.

The Kurdistan Front

During the Iran-Iraq War, the Kurdish nationalist movement in Iraq was still concerned with their self-determination. By the 1980s, the nationalist movement had split into the KDP and the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan (PUK). The PUK was initially focused on a peace agreement with the Ba'ath regime in 1983, but after negotiations collapsed, the PUK established stronger ties with both the KDP and Iran, according to "The Kurds in a New Middle East" by Cengiz Gunes.

In October 1986, PUK and Iranian forces launched a brief attack on the city of Kirkuk, Iraq, intended to "send a message" to the Iraqi government. According to "A Poisonous Affair" by Joost R. Hiltermann, the Iranian government used the attack as propaganda and claimed that the assault was a major and successful one despite the fact that it actually caused minimal damage.

The threat of a Kurdish-Iranian alliance was quickly recognized by the Iraqi government, who set out to retaliate against the Kurdish people. However, as Choman Hardi notes in "Gendered Experiences of Genocide," "it is unclear whether this collaboration with Iran was the main reason behind Anfal or whether it gave the government an excuse 'to solve the Kurdish problem' once and for all."

Chemical Ali

In early 1987, Hassan Ali Al-Majid was appointed head of the Northern Bureau by his cousin, President Saddam Hussein, and he was given unlimited powers with regard to addressing the Kurdish resistance. Before long, Al-Majid became known as "Chemical Ali" due to his flagrant use of chemical weapons against Kurdish civilians in Iraq.

According to Institut Kurde de Paris, Al-Majid's first chemical attack was executed on April 15, 1987, against roughly 30 Kurdish villages in the Sulaymaniyah and Erbil provinces. The villages were bombed with mustard gas and within several hours, NPR reports that children were some of the first to start vomiting from the exposure. Another chemical attack was also directed at the Balisan valley on April 17. Many women who were pregnant ended up miscarrying as a result of the chemical attacks. And when those who survived in the Balisan valley tried to go to Erbil for medical attention, they were shot by the army. It's unknown exactly how many died during these chemical attacks, but it's estimated that 400 people were killed in the Balisan attack alone.

According to "The Modern History of Iraq" by Phebe Marr, more than 500 villages were destroyed and occupied between April and June 1987, often using chemical attacks. After the attacks, Kurdish villagers would be displaced to camps where few survived.

The census of October 1987

Before the Anfal campaign started, the Iraqi government set out to delegitimize the Kurdish population in 1987. First, majority Kurdish areas were designated prohibited areas, a term that was given a broad definition. Directive 28/3650, signed on June 3, 1987, declared over 1,000 Kurdish villages to be in a prohibited zone and stated that "the armed forces must kill any human being or animal present within these areas," according to Institut Kurde de Paris.

Those living in prohibited areas also weren't counted in the 1987 census. According to "Origins of the Kurdish Genocide" by Ibrahim Sadiq, provinces like Sulaymaniyah saw their number of counted villages drop from 1,877 in 1977 to 186 in 1987. Although some of the villages were destroyed during the Iran-Iraq War, many villages were declared to be in prohibited areas and were ignored during the census taken on October 17, 1987.

Aram Rafaat writes in "Kurdistan in Iraq" that secondly, everyone who was excluded from or didn't manage to register for the census had their Iraqi citizenship revoked and was effectively made stateless. And anyone without Iraqi citizenship was declared an enemy of the state, as was anyone living in areas that were controlled by peshmerga, the Kurdish military forces. Through these measures, the Iraqi government effectively legalized the murder of Kurdish people.

The First Anfal

The First Anfal campaign took place between February 23 and March 19, 1988. Targeting the headquarters of the PUK in the villages of Sergalou and Bergalou in Jafati valley, the Iraqi army attacked the area with chemical rounds and bombs, hitting numerous villages including Yakhsamar, Bargallu, Chokhmakh, and Haladin. According to the Mass Violence and Resistance – Research Network, because Hassan Al-Majid had been using chemical attacks frequently, some of the PUK peshmerga had been able to stockpile gas masks and nerve gas antidotes by the time the First Anfal campaign started.

The PUK managed to fight back against the Iraqi army for three weeks, but by mid-March they were forced to retreat. Choman Hardi writes in "Gendered Experiences of Genocide" that the peshmerga cleared an escape path to Iran for people to escape through and although over 80 people froze to death during this escape, the majority made it into Iran safely. Unfortunately, those who were later convinced to return by the Iraqi army were executed.

In an attempt to split the Iraqi army's attention during the fighting, a group of PUK peshmerga and Iranian Revolutionary Guards occupied Halabja in March 1988. But this unfortunately led to a swift retaliation by the Iraqi army in the form of an intense chemical attack against the city, which had a population of almost 80,000. Thousands of people were killed in what became the largest chemical weapons strike against a civilian population, per Federation of American Scientists.

Emptying villages with chemical weapons

The Second Anfal campaign targeted Qara Dagh and the villages of Takiyeh and Balagjar (per Human Rights Watch) and took on the pattern that the subsequent campaigns would maintain. The campaigns typically proceeded in three steps: smoking out the Kurdish people with chemical gasses, destroying the villages, and displacing the people into camps or disappearing them, Aram Rafaat writes in "Kurdistan in Iraq."

Human Rights Watch writes that the chemical attack, which often consisted of both mustard and nerve gas, would also be accompanied by an air and ground assault to clear the area of people. And while some peshmerga had gas masks, civilians were defenseless against yellow-white smoke that smelled like insecticide and had a bitter taste. "When they fell, there was a loud explosion, a little smoke, and it was like salt spread on the ground. People who touched it ended up with blisters on their skin. Animals that ate the affected grass died instantly," said one eyewitness, via HRW. Nadje Sadig Al-Ali writes in "Iraqi Women" that chemical weapons were used so widely that everyone, including children and infants, suffered their effects.

This pattern of smoking people out with chemical weapons before destroying their villages occurred during every Anfal stage in 1988. Calls for fake amnesty would also be used to lure people out into the open in order to arrest them, per "Gendered Expressions of Genocide."

Destruction of villages

After Kurdish civilians were expelled from the villages with chemical weapons, the Iraqi army would move in and begin looting the village before running a demolition crew over it. Some residents would even be forced to watch the destruction as they were placed under arrest, per "Gendered Expressions of Genocide."

During the Anfal campaigns, over 4,500 Kurdish villages were destroyed, according to "Genocidal Nightmares," edited by Abdelwahab El-Affendi. After driving out the villagers with chemical weapons and calls of fake amnesty, the military units would take any and all property that they wanted. They were told, "You shall take any peshmerga's property that you may seize while fighting them. Their wives are lawfully yours (hallal), as are their sheep and cattle," per Human Rights Watch.

After being looted, many villages were burned up. Afterward, any trace of them was demolished by bulldozers as an entire community was razed to the ground. Ekurd writes that the Iraqi military were also sometimes assisted by Kurdish collaborators, known as the mustashar and the jash. In some areas, the jash and the military units didn't limit their destruction to Kurdish villages and destroyed some pro-regime villages as well.

Displacing people into camps

After the Iraqi military forced Kurdish people out of their villages, they were either confined to camps or disappeared. It's unknown exactly how many people were disappeared, but it's estimated to be in the tens of thousands, per "Kurdistan in Iraq." The number of civilians who were disappeared is also directly related to how much of a foothold the peshmerga resistance had in the area, per "Gendered Expressions of Genocide." Author Choman Hardi writes that the Third Anfal, which was carried out in the Garmian region, was notorious for having one of the largest disappearances of Kurdish civilians, with an especially large number of women and children being disappeared. However, it's unknown exactly why the area would have been so especially targeted by the Iraqi government.

Those who survived the chemical assault and arrests would be taken to camps near Kirkuk, Tikrit, Dibs, and Nugra Salman, among others. There was even one prison camp where primarily elderly people were imprisoned.

Kurdish people imprisoned in the camps were frequently physically and sexually abused, according to Human Rights Watch. Disease also spread quickly through the unsanitary camps, and many died from illnesses and starvation. Those who died were denied a dignified burial and were frequently ignored and left by the prison guards on the spot where they died.

Eight Anfals

The Kurdish genocide took place over eight Anfal campaigns, lasting from February to September 1988. During the eight Anfal stages, the Iraqi government targeted the Jafati valley, Qara Dagh, Germian, the Lesser Zab valley, the valleys of Shaqlawa and Rawanduz, and Badinan, according to Human Rights Watch. The Fifth, Sixth, and Seventh Anfal campaigns all targeted the same area due to the fact that the Fifth Anfal failed; Choman Hardi writes that repeated offensives were required by the Iraqi army to take control of the area.

The Anfal campaigns were committed in broad daylight, literally and metaphorically. The Iraqi media would report on the "heroic Anfal campaigns" and its military operations against civilians weren't kept a secret, according to "Origins of the Kurdish Genocide." The international community, including the United States, was also well-aware of the genocide that was being committed, but only former President Ahmed Ben Bella of Algeria issued any statement against the Iraqi government.

Mohammed Shareef writes in "The United States, Iraq and the Kurds" that because the United States and other countries saw Iraq as an ally against Iran, they were more than willing to ignore Iraq's use of chemical weapons against both Iranians and its own civilians.

General amnesty of September 1988

After eight long months of a genocidal campaign, President Saddam Hussein proclaimed general amnesty toward all Iraqi Kurdish people inside and outside the country on September 6, 1988. Human Rights Watch writes that although many people were released from the prison camps and some returned from exile, they were given no support upon their return when they found that they had no villages to which to go back. And those who were returning from exile were given only one month to return, per Mass Violence and Resistance – Research Network.

As Achim Rohde notes in "State-Society Relations in Ba-thist Iraq," "this amnesty was no less than a declaration of victory, as by then all organised armed Kurdish resistance had been crushed." The Anfal campaigns mainly targeted PUK strongholds because, according to Kurdish media group Rudaw, the Iraqi government considered the PUK to pose a bigger threat. As a result, there were still pockets of Kurdish resistance that remained, but overall the population of the Kurdish people was decimated.

And despite the general amnesty, many Kurdish people continued to be arrested and murdered. One report claims that a Kurdish man was executed in 1989 simply for "teaching the Kurdish language in Latin script" (via Human Rights Watch). Even those in pro-regime villages found their villages razed to the ground by 1989.

Tens of thousands killed

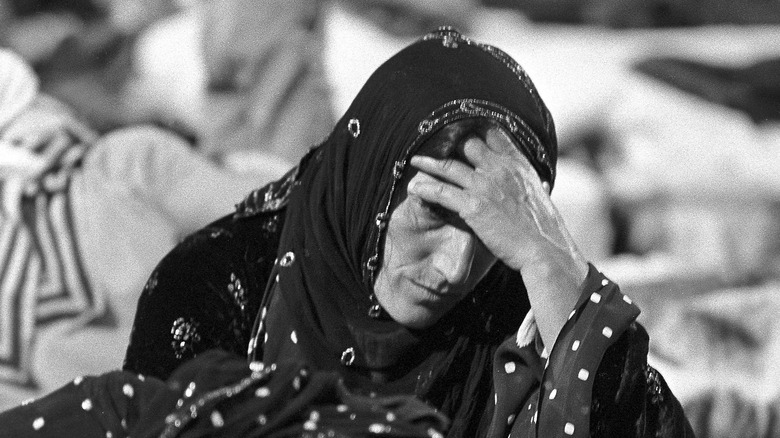

Reports vary as to exactly how many people were murdered during the Kurdish genocide, ranging from 50,000 up to nearly 200,000 people, according to PBS. Roughly 160,000 Kurdish people fled to Iran and Turkey as they were displaced, writes Aram Rafaat in "Kurdistan in Iraq," while another 500,000,the majority of whom were elderly people, women, and children, were resettled. According to "Gendered Experiences of Genocide," most Kurdish men between the ages of 15 and 50 were targeted during the genocide and as a result, they either fled or were murdered.

According to "Genocidal Nightmares," up to one million Kurdish people were displaced by the genocidal Anfal campaign, representing roughly one-third of the Kurdish population in Iraq. And Kurdish people weren't the only ethnic group targeted by the Anfal campaign. Assyrians, Chaldeans, and Yazidi people were also ignored in the October 1987 census and thus part of the purge. And Choman Hardi writes that because the general amnesty only applied to Kurdish people, they weren't given any chance to return to their homeland.

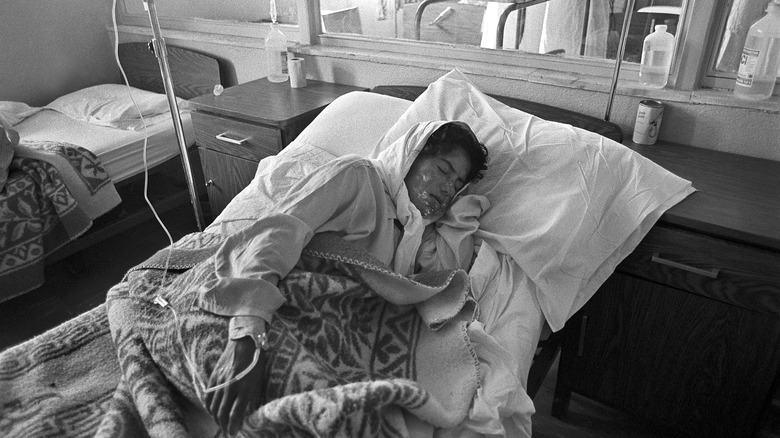

Many who survived the genocidal Anfal campaign also found their health in a precarious condition due to the chemical attacks. PLoS One writes that many who were subjected to chemical attacks ended up with lifelong respiratory conditions. Among some survivors, cancer, sterility, and congenital abnormalities were also discovered at extremely high rates, per "Forgotten Genocides," edited by René Lemarchand.

The Anfal trial

On August 21, 2006, the Anfal trial began against Saddam Hussein, Ali Hassan al-Majid, General Sultan Hashem Ahmed al-Ta'i, Hussein Rashid al-Tikriti, Sabir Abdul-Aziz al-Duri, Tahir Tawfiq al-Ani, and Farhan Mutlak al-Jubouri. All seven were charged with war crimes, genocide, and crimes against humanity relating to planning and subsequent murders and disappearances of tens of thousands of Kurdish people during the Anfal campaign. According to the International Center for Transitional Justice, after Hussein's execution on December 30, 2006, following the Al Dujail trials, the Anfal legal case resumed concerning only the remaining six defendants.

All the defendants maintained their innocence during the Anfal trial. According to "The Limits of Trauma Discourse" by Karin Mlodoch, the defense claimed that all of their actions had been part of a war against Kurdish rebels, rather than a genocide, and that they weren't personally liable for what had happened. Even Al-Majid claimed that he had done nothing wrong in ordering the attacks during the Anfal campaign. "I am not apologising... I did not make a mistake," he said, per Al Jazeera.

While al-Ani was acquitted due to a lack of evidence, the other five defendants were found guilty with sentences ranging from life imprisonment to death, writes the International Crimes Database.

Legacy of the genocide

Since the fall of Saddam Hussein's Ba'ath regime in 2003, numerous mass graves have been discovered that are connected to the Kurdish genocide. In 2019 alone, four mass graves were discovered in the al-Muthanna province, reports Al Jazeera. As of 2021, 63 mass graves in total had been discovered. But according to Medya News, the process of returning bodies so that they can be buried in their homeland is moving slowly.

Despite the fact that the Anfal campaign can be accurately described as a genocide, the Iraqi government is the only government in the world that recognizes it as such. Al Jazeera reports that although the British, Swedish, Norwegian, and South Korean parliaments all agree that the Anfal campaigns meet the definition of genocide, they stop short at official recognition because otherwise they could be held accountable for arming Iraq at the time.

In 1991, collaborators of the Anfal campaign were given amnesty by the Kurdistan Front coalition, according to the London School of Economics. And although over 250 arrest warrants were issued for Kurdish collaborators by the Supreme Iraqi Criminal Tribunal in 2010, many continue to avoid accountability due to their powerful connections. Over 30 years later, the families of the victims of the Kurdish genocide are still fighting for recognition and justice.