Independent Countries That Lasted Less Than 20 Years

According to the World Population Review, there are at least 195 countries in the world (if one goes by U.N. member status). But there have been countless countries, empires, and kingdoms that are now lost, having fallen or grown into something new. Many of these countries lasted at least a century. But some never made it that far. In fact, there are many that never even made it past two decades.

Many of the countries that had short lifespans may have been quite successful had they survived but were victims of their circumstances — namely war. Many places were born from conflict and in conflict they died, unable to forge a country while fighting expensive wars of survival. Others were strange creations — the product of nationalistic adventurers seeking glory. And then there are some that simply voted themselves out of existence, choosing to join larger federations. Here are some countries that failed to make it past the 20 year mark — and in most cases, didn't even make it to 10.

Free City of Danzig

The Baltic city of Danzig (modern Gdansk) was disputed in 1918 between the nascent Republic of Poland and Germany, which lost the city under articles 100-108 of the Treaty of Versailles. According to The Geographical Journal, Poland coveted Danzig's port for access to the sea. However, Danzig was also a majority-German city. So the League of Nations (predecessor to the U.N.) compromised by creating the Free City of Danzig in 1920. Poland would maintain access to the port facilities.

Danzig made it into the 1930s intact, but according to The Jewish Chronicle, tensions over reunion with Germany simmered, especially once the revanchist Adolf Hitler came to power. Nazi sympathizers became increasingly bold, taking control of the Free City of Danzig government by 1937. Jews and Poles were targeted for discriminatory measures, including property confiscation, internment, and forced labor.

By 1938, Germany was demanding discussions for Danzig's return to Germany on the basis of demographics, according to the Imperial War Museum. Eventually, Hitler sent Poland an ultimatum: Return Danzig or Poland would be invaded. Poland refused to withdraw from Danzi, so on September 1, 1939, the German battleship Schleswig-Holstein fired upon Polish targets in Danzig. The city was reincorporated into Germany and became notorious for hosting the very first shots of World War II.

Republic of Corsica

The Republic of Corsica arose in 1755 following a rebellion against the Republic of Genoa, according to Prussian historian Ferdinand Gregorovius' book "Wanderings in Corsica." To lead the island to independence, the revolutionaries turned to exile Pasquale Paoli, who was declared general and president of the republic.

The republic's chief achievement was the creation of a constitution based on the idea that authority was derived from the consent of the governed (in American parlance, We the People). It established a parliament that had the sole authority to pass laws with a majority vote and a judicial system. As Gregorovius also notes, Paoli established a school system co-opting the Corsian Clergy as instructors, along with a university

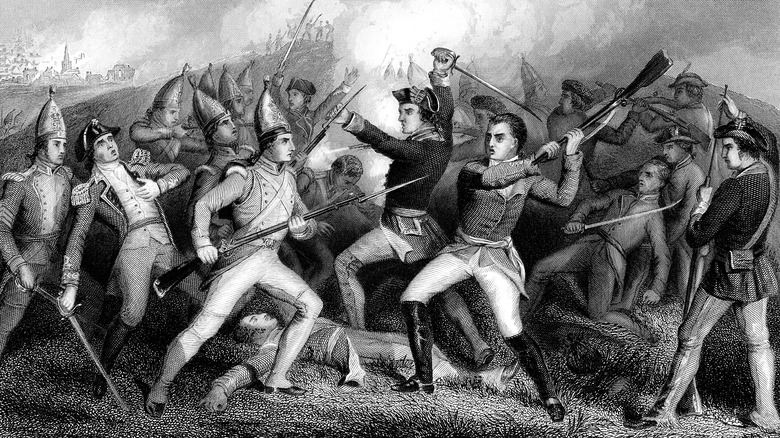

Corsica survived for 14 years despite Genoese attempts to retake the island. Hoping to profit off Corsica even in defeat, Genoa sold the island, which it still viewed as its own, to France in 1768. The French invaded the island soon thereafter. Despite a victory at Borgo, the outnumbered Coriscans suffered a decisive defeat at Ponte Nuovo, a Genoese bridge over the Golo River. Despite a valiant defense, the army fell apart when Prussian mercenaries fired on their own men. Paoli fled along with his confederates, and Corsica has remained a French possession ever since.

Republic of Vermont

Vermont is not exactly known for secessionism, but that's all it was known for during the American Revolution. According to the American Antiquarian, the republic originated in a land dispute between New York and settlers such as Ethan Allen of the Green Mountain Boys militia. Despite the problems, Vermont sided with the Continental Congress against Britain in 1775, scoring the first victory of the revolution by capturing Fort Ticonderoga.

Having proven themselves, Allen and other prominent Vermonters petitioned the Continental Congress to be admitted to the new United States as the 14th colony. Congress rejected their petition, so the Vermonters decided to declare independence, issuing a declaration to that effect in 1777.

The self-declared state did quite well. At home, it established a constitution that abolished slavery and guaranteed voting for all free men, and made Sabbath observance obligatory. On the battlefield, Vermont militia, together with American forces, scored a victory against a detachment of British Gen. John Burgoyne at Bennington. This victory deprived the British of supplies and soldiers, enabling the American victory at Saratoga -– the turning point of the revolution.

After the revolution, Vermont continued to be de facto independent, despite being considered in rebellion against the U.S. Per the Vermont Historical Society, relations deteriorated when Vermont attempted to annex parts of New Hampshire, but the ties with their fellow colonists ultimately proved too strong. After protracted negotiations, Vermont finally got its wish and joined the U.S. in 1791.

Republic of Yucatan

According to the Yucatan Times, when Mexican Gen. Antonio Lopez de Santa Ana abolished the federal constitution in 1835 and centralized power to Mexico City, a wave of separatism swept Mexico. Texas seceded first in 1836 (via History). Yucatan followed in 1840.

But in 1840, Mexico was not in a fighting mood. Having lost Texas, it wanted to limit further land losses. So Santa Ana sent Yucateco Andres Quintana Roo to successfully negotiate Yucatan's re-entry into Mexico. But when Mexico City did not honor its promise of Yucateco autonomy, Santa Ana sent soldiers to take the peninsula by force -– and was defeated. So Santa Ana settled on economically isolating Yucatan, which worked until a new agreement was worked out in 1843.

In 1846, the Mexican-American War broke out. Yucatan, according to Mexico's UNAM, declared itself neutral in the war, effectively setting itself up as an independent state once again. When it seemed Yucatan might maintain independence as Mexico was crushed, losing 55% of its territory to the U.S., per the Library of Congress, the indigenous Maya population threw Mexico a lifeline.

In 1847, a Mayan revolt against the mestizo and Spanish elites broke out in Yucatan. This war, known as the Maya Caste War, put the Yucateco elite in a bind. It was either surrender to the rebels or risk occupation by President James Polk and the U.S. military. The third option was re-integration into Mexico in return for crushing the revolt. They settled on this, and in 1848, the Republic of Yucatan came to an end.

Free Territory of Trieste

The Free Territory of Trieste was, per the Western Political Quarterly, a compromise to try and satisfy the Allied powers, Yugoslavia, and the USSR. The USSR saw Trieste in the hands of its fellow communists in Yugoslavia as a springboard to further expansion in Europe. Yugoslavia, which had annexed historically Italian areas in Dalmatia and Istria and ethnically cleansed them, was eager to take Trieste too.

The Allies and the USSR agreed in 1947-48 to create an independent, neutral state. It would allow Italy, Yugoslavia, and Central European states to use the port of Trieste, and there would be no further communist expansionism. British and American forces occupied Trieste proper (Zone A) while Yugoslavia administered the south, per Britannica (Zone B).

Problems began from the get-go. First, neither the USSR nor the Allied powers could agree on a governor of the territory. They kept vetoing each other's candidates. Second, and more pressing, was the fact that Trieste's Italian population wanted to rejoin Italy. In 1953, riots broke out after British forces forbade the flying of the Italian flag. As British Pathe reported at the time, Italian students rose up, reinforced by their countrymen who came to the city specifically to join the melee. Six were killed, and 162 were injured.

Despite calls for "firm action" against the Italian population, the riots were the final straw for the exhausted Allies. In 1954, the U.S., Britain, Italy, and Yugoslavia signed a new accord dismantling the Free Territory and returning Trieste to Italian rule. Today, the city celebrates the reunion with Italy every October 26 (via RAI News).

Chechen Republic of Ichkeria

When the USSR collapsed, the new Russian Federation struck deals with its numerous ethnic minorities to create autonomous enclaves, per the National Interest. Muslim Chechnya, however, refused and seceded from Russia in 1994.

According to Stanford University, the new state under President Dzhokhar Dudayev styled itself the Chechen Republic of Ichkeria. But Boris Yeltsin's Russia was determined to crush the separatists and invaded Chechnya. With the Russian army understrength and demoralized from the USSR's collapse, the Chechens managed to win the war. Under the Treaty of Khasavyurt, the conflict ended, and Chechnya became de facto independent.

While Chechnya managed independence, governing the fractured state proved to be the real challenge. In addition to lacking a centralized governing body, the state gradually fell under the influence of hard-line Islamist warlords. Chief among these warlords was Shamil Basayev, who became confident enough to strike Russian positions in Dagestan in 1999, as per Radio Free Europe. In response, Vladimir Putin ordered a fresh invasion of Chechnya.

According to Radio Free Europe, by March 2000, Russia had concerted control over the republic, with the capital of Grozny leveled to the ground. While Chechnya was reincorporated into Russia, fighting continued — by 2009, when Russia claimed the conflict had ended, some 80,000 civilians were killed. However, as of 2022, some believe that Chechnya never lost its independence but rather is temporarily occupied by Russia (via the Kyiv Post).

The Republic of el-Rif

According to the International Journal of Middle East Studies, Northern Morocco -– the area encompassing the Rif Mountains -– came under Spanish rule as a result of a joint protectorate that placed the rest of the country under French rule in 1912. However, the Berber-speaking inhabitants of the Rif had no interest in being ruled by European Christians and promptly rebelled.

Led by warlord Muhammad Abd al-Karim, the Riffian Berbers defeated the Spanish forces sent to defeat them in 1921. But Abdel-Karim had greater ambitions –- to create a republic modeled on European antecedents but with an Islamic character.

In 1923, Abdel-Karim, per Britannica, proclaimed the Republic of the Rif. His goal was to unite the Berbers of Northern Morocco into a single unified state that could pose long-term resistance to European colonialism. His government took control of justice from local tribes and imposed Sharia to provide a common law.

The new state, however, never got past rudimentary organization due to internal divisions between the fractious Berber tribes of the Rif and the hardships of war. As the war with Spain dragged on, taxes went up, men were conscripted, and economic conditions deteriorated. Disenchanted tribes rose up against Karim and each other. In an attempt to save his nascent state, Karim began negotiations with Spain and France in 1926, but they failed. A combined offensive that year finally crushed the Rif. Abdel-Karim and his family were spared but spent the next 21 years in exile on the remote Indian Ocean island of Reunion.

Republic of Vevcani

In 1991, per the BBC, Yugoslavia was collapsing on itself. Among the new countries was the Republic of Macedonia. But there was a small village of around 2,000 people called Vevcani, which was in an interesting position that set it up to become a short-lived micronation.

As the BBC notes, Vevcani was located in the Struga municipality of Macedonia –- a majority-Muslim, Albanian-speaking region on the border with Albania. Vevcani, however, had remained Orthodox despite nearly seven centuries of Ottoman Muslim rule. So when Macedonia became independent, the villagers decided they did not want to be part of Struga and voted to secede from Macedonia.

Now, Macedonia never recognized the Republic of Vevcani. It seemed more of a ploy for attention than anything else. But there was a logic behind it. Macedonia was facing an Albanian separatist insurgency at the time, which sought to detach parts of Macedonia to join Albania. Christian, Macedonian Vevcani had no interest in joining Albania. The independence referendum was to draw attention to Vevcani's desire to separate from the Albanian-majority Struga and avoid becoming drawn into the conflict. It worked, as in 1994, Macedonia separated Vevcani from Struga.

Today, the story of the Republic of Vevcani is a bit of a tourist gimmick. The village sells passports, coins, and even has its own flag. Visitors can have these "passports" stamped by local authorities. Obviously none of this has any official meaning, but it's still a great way of attracting curious tourists to a place no-one would otherwise visit.

Regency of Carnaro

According to the National World War I Museum, Italy had entered World War I in return for the promise of historically Italian territories in the Adriatic. In 1918, however, these territories went to the Kingdom of Kingdom of Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes (now Yugoslavia).

Crisis soon brewed in the ethnically mixed city of Fiume (modern Rijeka). The Italian population was the largest group at 46.9% (via Central European Horizons) and was in favor of union with Italy. The city followed through on this sentiment in 1918, declaring its annexation to Italy and called on Italian forces to occupy the city.

Italian poet and nationalist Gabriele d'Annunzio answered Fiume's call. In 1919, per History Today, he marched on Fiume with a small force of men, captured the city, and created a new state called the Regency of Carnaro. D'Annunzio became the state's leader, wielding both military and civilian power. News of his feat spread like wildfire, as young Italian nationalists flocked to join the new state in anticipation of annexation to Italy.

Strangely, Italy did not annex Fiume –– even after d'Annunzio had done all the heavy lifting. Instead, Italy invaded Fiume, dislodged d'Annunzio, and signed the Treaty of Rapallo, creating the independent Free State of Fiume. This state lasted a little longer than the Regency of Carnaro, making it four years before Benito Mussolini and the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes split it up with the 1924 Treaty of Rome.

Socialist Republic of Gilan

The Socialist Republic of Gilan emerged from the chaos that followed the Iranian Constitutional Revolution of 1906. According to the Encyclopedia Iranica, a former religious student and local warlord Mirza Kuchak Khan began a guerrilla movement during World War I in the northern Iranian region of Gilan in opposition to Russian and British occupation.

In 1920, the Soviets attacked the northern Iranian port of Enzeli, per Russia Beyond, seeking to capture or destroy the Tsarist fleet stationed there and withdraw. Instead, however, they connected with Kuchak Khan, seeing that they shared a common foe in the British and an opportunity to introduce communism into Iran.

Thus, the Soviets decided to offer Kuchak Khan weapons, money, and support. In return, the warlord established a state called the Socialist Republic of Gilan, which was meant to spread its influence south until it eventually comprised an Iranian communist republic.

In the end, however, the gambit failed, mainly because Kuchak Khan was happy to govern his little slice of Iran without taking over the whole country. Thus, Soviet-backed Iranian communists deposed him and his followers and drove him into the mountains. The republic then attacked the government in Tehran and was heavily defeated. The Soviets withdrew support, concluded a treaty of friendship with the Tehran government, and the Gilan republic ceased to exist by May 1921.

Republic of Sonora

A product of the filibustering and Manifest Destiny eras, the Republic of Sonora was the brainchild of adventurer William Walker. According to Britannica, Walker was a staunch supporter of American expansionism and slavery, which he sought to spread into the sparsely inhabited areas of Northern Mexico.

According to the City Museum of San Francisco, Walker believed that the Northern Mexican regions of Sonora and Baja California could be easily conquered, settled by Americans, and eventually annexed to the U.S. as slave states -– maintaining a balance between slave and free states in Washington D.C.

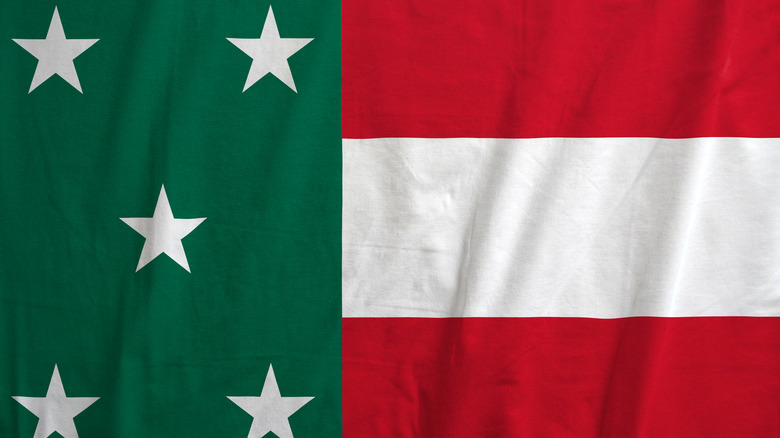

Walker tried to accomplish his scheme peacefully at first with a land grant from Mexico. He was rebuffed, so in 1853 he recruited a force of men mostly from the slave states of Kentucky and Tennessee and captured first the city of La Paz. After Mexican forces counterattacked, he captured Ensenada and declared the Republic of Sonora, signaling his intention to take all of Northwest Mexico. The new state's laws followed those of Louisiana, making slavery legal.

The new state was a hit in California. Walker set up recruiting offices there as young men signed up to join him. Sonora even sold bonds to finance its existence. But the difficulties were too much for Walker. Undersupplied and faced with resistance from Mexico City, Walker abandoned the venture in 1854 and was hit with federal charges of violating American neutrality. The San Francisco jury acquitted him anyway, leaving him to try a much more successful filibustering expedition to Nicaragua in 1855.

Carpatho-Ukraine

The mountains of Eastern Slovakia and Southwestern Ukraine are home to the Carpatho-Rusyns. In 1918, according to University of Chicago Slavicist Clarence Manning, the territories of Carpathian Rus all fell inside the newly formed state of Czechoslovakia. However, the Rusyns were culturally distinct from their Czech overlords and Slovak neighbors, being closer linguistically to Ukrainians.

In order to bring some sort of order to the country, the Czechoslovak government –- dominated from Prague -– promised to create a Carpatho-Rusyn autonomous zone, where the Rusyns would have some degree of self-governance. However, the agreement was never really enforced.

When Adolf Hitler's Germany dismembered Czechoslovakia in 1938, the Rusyn lands -– known as Carpatho-Ukraine –- declared independence. The independent Republic of Carpatho-Ukraine, per the Library of Congress, came into existence on March 15, 1939, electing Greek Catholic priest Rev. Auhustyn Voloshyn as president. The only problem? The country was already under attack from Hungary –- its old overlord from before World War I.

Although the republic was declared on March 15, fighting against Hungarian forces had already begun the day before, as Hungary, with Hitler's support, sought to regain territories it had lost in 1920. Germany had originally been sympathetic to the Rusyns. But in order to assuage Soviet dictator Joseph Stalin's fears that the new state would encourage Ukrainian nationalism in the USSR, the Germans allowed Hungary to annex it. Hungarian forces overran the republic in less than a day. By the evening of March 15 -– the same day as Voloshyn's election -– the country was gone.