What Really Happened During The Longest Indigenous Revolt In History

Mesoamerica was once home to numerous indigenous societies, including the Olmec, Zapotec, Maya, Toltec, and Aztec. During the time of Spanish colonization, many of the indigenous cultures of the time were destroyed and indigenous populations were decimated, but although this story is often told as a one-way act of destruction, there was a great deal of resistance that sought to combat colonization.

One such act of resistance was the continued revolt of the Maya people. Throughout Spanish and Mexican colonization, groups of Maya maintained an armed resistance that lasted almost a century and at times were able to maintain a sovereignty that was recognized. And in addition to being one of the longest indigenous rebellions in history, it's also considered to be one of the "largest and most successful" indigenous rebellions in the world.

Although it's debatable exactly how successful the Maya war can be considered to be, there's no denying that the decades-long indigenous revolt forever affected the history of Yucatán. Here's what really happened during the longest Indigenous revolt in history.

Maya before colonization

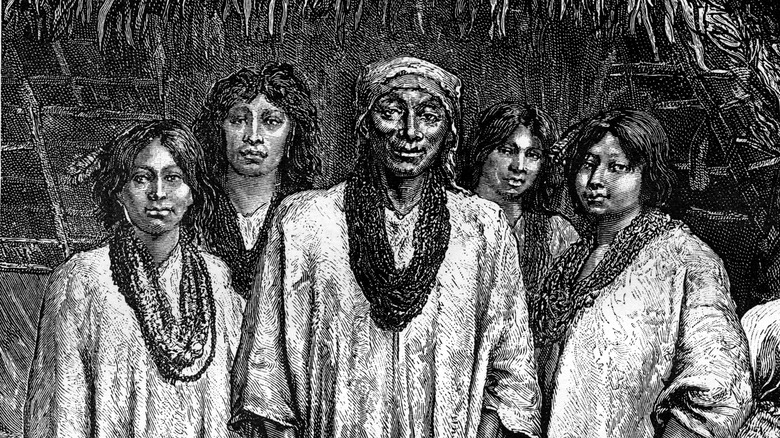

A few centuries before the colonization of the Yucatán Peninsula and Mesoamerica in a period referred to as the Post Classic Maya period, the Maya people lived in numerous settlements across the region, including the cities of Mayapan, Uxmal, and Chichén Itzá. Between the 11th and the 14th century, these three cities formed an alliance known as the Mayapan League, according to "The Ancient Maya of Mexico," edited by Geoffrey E. Braswell.

However, by the 1300s, the armies of Chichén Itzá attacked Mayapan forces, and in response, the leader of the Cocomes Ah Nacxit Kukulcan, also known as Hunab (Hunac) Ceel, conquered Chichén Itzá. Although this established the hegemony of the Mayapan for a century, "the driving force of the League meanwhile had been permanently weakened" and after an uprising in 1441 led by the Xiu Dynasty of Uxmal, Mayapan was conquered and the League "completely collapsed," C.W. Ceram writes in "Gods, Graves, and Scholars." Numerous independent states rose up instead and were widespread across the peninsula when the Spanish arrived in Central America in the following century.

Yucatán colonization

The Maya people encountered Spanish colonizers in the Yucatán peninsula around the 1510s, at which point their centralized political society had already dissolved. At the time, it's estimated that there were around two million Maya people in Mesoamerica, making up 40% of Central America's indigenous population, according to the Armstrong Undergraduate Journal of History.

Sergio Quezada writes in "Maya Lords and Lordship" that because the Maya didn't have the same centralized power structure as the Aztec people, this made the conquest of the Yucatán a "prolonged and grueling campaign" and from the moment their conquest was authorized by Spain's King Charles V in 1520, Maya people fought against the conquest of Yucatan. The bulk of the fighting lasted until 1547, when "most of the remaining Mayan strongholds in Yucatan were overthrown." After one of the last rebellions was suppressed in March 1547, Quezada writes that the south of the Yucatán peninsula became "a zone of refuge where the Maya escaped from colonial rule" while the rest of the peninsula was added to the colony of New Spain.

Franciscan Catholics were also intrinsic to the colonization of the Yucatán up to the 1560s and held an inquisition in 1562 to "eradicate Yucatan of remaining traces of pre-colonial Mayan religious beliefs."

First declaration of independence

By the 1680s, the Maya population in the Yucatán was decimated by Spanish colonization to no more than 100,000 people. By the time Spanish colonization ended, "there were still barely a fifth as many Mayas in highland Guatemala and Yucatán as there had been three centuries earlier," according to "Beyond Black and Red." In "The Conquest of the Last Maya Kingdom," Grant D. Jones writes that the Itza ended up becoming the last unconquered Maya kingdom, but they were ultimately defeated by Spanish troops in 1697.

But indigenous uprisings against the Spanish didn't subside under colonization. The Yucatan Times writes that the Canek rebellion of 1761, led by Jacinto Canek, was one such uprising that sought to end Spanish colonial domination. However, the uprising was unsuccessful and Canek was condemned to be "tortured, his body broken, and thereafter burned and the ashes scattered to the wind," according to Recovering Lost Footprints by Arturo Arias.

Yucatán declared independence in May 1823, but it joined the Federal Republic of the United Mexican States by December 1823 and was given special status as the Federated Republic of Yucatán. Although the Yucatán government tried to build a separate relationship with both its indigenous and non-indigenous population, "the liberal claim that indígenas were an obstacle to economic growth left [indigenous people] vulnerable, as pressures on the villages for land, labor, and political control increased," Karen D. Caplan writes in "Indigenous Citizens."

Second declaration of independence

In 1834, troops from Mexico came to Yucatán and installed Francisco Paula Toro as the state governor after dissolving the Yucatán Congress. And after Governor Toro passed a "series of measures that directly affected the state and its commercial and economic interests," according to Armed conflict, disease, and death by Paola Peniche Moreno, there was an uprising led by Santiago Imán y Villafaña and in October 1841, Yucatan declared independence for the second time. In "Moral Ecology of a Forest," José E. Martínez-Reyes writes that Imán recruited "Maya peasants and other poor rural folks" and "enticed them by promising to eliminate the much-hated church taxes."

After General Antonio López de Santa Anna took control of Mexico after a military coup d'etat, he tried to revoke Yucatán's independence. Santa Anna sent 3,000 troops to retake the cities of Campeche and Merida in the Yucatán peninsula, but the Mexican army ended up admitting defeat to yellow fever and retreating.

The Yucatán Times writes that "everything seemed to indicate that Yucatán would remain independent." However, the Hispanic American Historical Review writes that the peninsula was about to face an indigenous uprising in response to the "process of commercial agricultural expansion" that was overtaking the land.

Introducing private property

After the second Republic of Yucatán was created, a new agrarian policy was introduced that was intended to bring property rights and "modern capitalism" to the people of Yucatán. This new policy was instituted through two laws. The first law limited the size of community land, also known as ejidos, and "eliminated whatever legal basis the peasant farmers might claim for maintaining milpa outside a limited confine." And the second law "legitimated paying veterans of the war against Mexico with land instead of back wages." Priests and landowners were also repaid with land since they had lent money to the military campaign.

One of the agricultural methods of the Maya involved what was known as slashing-and burning. Terry Rugeley writes in "Rebellion Now And Forever" that farmers would cut and burn the overgrowth on the land for farming and then after one or two years would move onto fallow land. This process of movement was essential to the recovery of the land but now, Maya people didn't have enough land to rotate.

According to "Moral Ecology of a Forest," between 1840 and 1847, up to 460,000 hectares of public lands were turned into private property. In "Yucatán's Maya Peasantry and the Origins of the Caste War," Rugley describes the land grab after Imán's revolt as "one of the most audacious land grabs in Mexico's history." Private landowners, including Imán, reaped the majority of the benefit of this redistribution.

Assassination of Manuel Antonio Ay

Around the end of July 1847, Manuel Antonio Ay, the Maya batab (local village head) of Chichimilá was arrested by authorities in Valladolid. There are various explanations for his arrest. In "Recovering Lost Footprints Vol II," Arturo Arias writes that Ay's arrest was ordered by Yucatan governor Santiago Mendez "under the pretext" that a letter from Cecilio Chí was discovered on him about a planned uprising. Meanwhile, according to "Moral Ecology of a Forest," Ay was actually discovered with such a letter by the mayor of Chichimala.

But regardless of whether or not the letter was fabricated, Ay was likely involved with the rebellion and the government's response was all too real. On July 26, 1847, Ay was tried, found guilty, and executed by hanging in the plaza of Santa Ana in Valladolid. Yucatecan authorities also subsequently attacked the town of Tepich "in search of other leaders, burning the town and repressing its inhabitants." Arrest warrants were also put out for Jacinto Pat and Chí, two other Maya leaders.

Between a week or two after the attack of Tepich by Yucatecan authorities, Chí and Pat launched their own attack on the town. This time, the violence was directed at non-Maya people and almost all in the town were killed. Some accounts report that this included "Criollos, Mestizos, and mulattoes." This was considered to be the beginning of the ba'atabil kichkelem Yúum, also known as the Caste War of Yucatán.

Maya revolt

Led by Pat and Chí, Maya were led in a campaign against "the entire white population" in Yucatán and within a year, Maya people had gained control over Quintana Roo. The Yucatan Times writes the first few years of the war were also some of the bloodiest, with many white and Maya fighters killing indiscriminately. The Yucatán government also sold captured Maya people into enslavement in Cuba, according to "The Mexican Revolution In Yucatan, 1915-1924" by James C. Carey.

Pat and Chi were also both assassinated in 1849, just two years into the war, "by internal, competing Maya factions." In Moral Ecology of a Forest, Martínez-Reyes describes the death of the two leaders as "the end of the first phase of the war." However, according to The Modern Maya and Recent History by Richard M. Leventhal, Carlos Chan Espinosa, and Cristina Coc, "although multiple Maya factions worked in concert during the war, their forces were never truly united."

Maya people continued to fight until 1850, at which point they retreated to Quintana Roo. Although some Maya agreed to a peace arrangement in 1853, others in the region continued to fight and would remain "de facto outside government control" for almost another 80 years. Yucatán also rejoined Mexico a year after the Maya revolt began, due to the fact that the Mexican Republic offered Yucatan financial and military assistance against the indigenous rebellion. Almost 1,000 U.S. volunteers were also hired by the Yucatán government to fight.

Land and taxes

By 1850, most of the Mayan forces were sequestered to the state of Quintana Roo. It's not clear why the Maya forces didn't take over the entire peninsula, but by mid-1848 they retreated and were soon "driven eastward by a renewed Yucatecan military, beginning a 50-year period of isolated fighting and ongoing resistance by the rebels," according to Heritage. Meanwhile, it's believed that around 250,000 people died or were displaced during the first few years of the war alone.

The Journal of Latin American Anthropology writes that the rebellion was largely made up of Maya peasants who were fighting for "the abolition of head tax and free access to agricultural land." When the Maya had joined Iman's army against Mexico, they had been promised the abolition of the religious peasant head tax required by the church also known as obventions. But the taxes weren't abolished after Yucatán independence and became one of the incentives behind the Maya revolt. But during the war, "Rebellion Now and Forever" writes that "war-related hardships gave new pretext for a piecemeal end to obventions" and by the mid 1850s, the major obvention was finally ended. This is likely what caused some of the Maya forces to agree to the peace agreement.

HistoricalMX also notes that there wasn't a clear-cut divide between Maya and non-Maya people due to the fact that some batabs "willingly acted as middlemen between Mayas and the regional government," underlining the class dimension of the conflict.

The talking cross

Some of the Maya forces established the town of Noj Kaj Santa Cruz Balam Ná in Quintana Roo, now known as Carrillo Puerto. And according to Moral Ecology of a Forest, it was here that they found a wooden cross that talked to them in 1848. The Maya created a new religion around the cross, combining elements of "Christianity with Maya cosmology," which became known as Cruzo'ob Maya, or the Cult of the Talking Cross. The place where the cross reportedly appeared is now a shrine known as Chan Santa Cruz. Chan Santa Cruz also ended up becoming "the de facto name of the Maya political entity" in Yucatán.

The cross reportedly gave two messages to Manuel Nahuat, who gave voice to the cross, and Juan de la Cruz, who interpreted the messages, although this may also have been a pseudonym for Atanasio Puc. Spoken in local Maya dialect, Mexico Unexplained writes that the message of the cross had two themes, "God's love and resistance."

The talking cross became an inspiration for many Maya people and some as far as Honduras and Guatemala were inspired to relocate to Chan Santa Cruz. The Maya state's sovereignty was also recognized by the British Empire, which "entered into treaties and trade agreements with the new Maya nation of Chan Santa Cruz." However, this only lasted until 1893, when the British Empire signed the Spenser-Mariscal Treaty, agreeing to help the Mexicans regain the Yucatán peninsula.

An unofficial end

The Cruzo'ob Maya maintained their independent state and its capital at Chan Santa Cruz for almost 50 years. The Yucatan Times reports there was even a peace treaty almost negotiated between the Maya people and the Spanish Yucateco state in 1884. However, the day after the signing of the treaty, the Yucatecan representative, General Teodosio Canto, insulted Antonio Dzul, a Maya batab, and the Maya "denounced the treaty and left in anger."

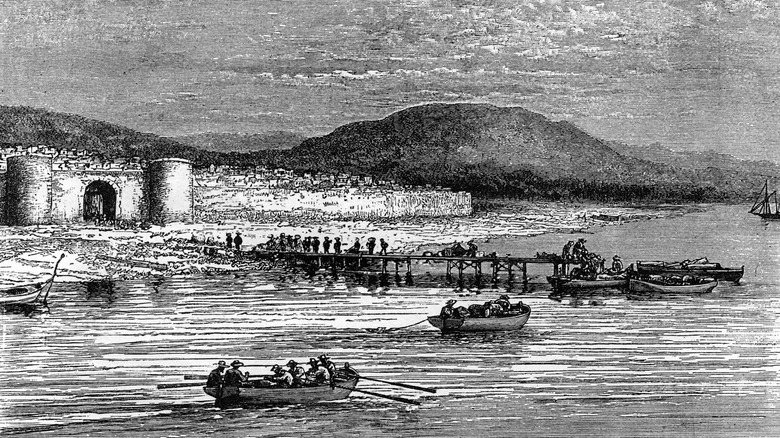

After fighting of varying intensity for over 50 years, the war came to an unofficial end in 1901 when General Ignacio A. Bravo led a military campaign and took over Chan Santa Cruz, according to Armed conflict, disease, and death. However, there was little battle over the city, which was abandoned, and the Speaking Cross had been taken from its shrine to a secret location preemptively.

General Bravo ended up creating a new administration in Chan Santa Cruz under the government of the Yucatán, which lasted for 11 years, while continuing to carry out "systematic persecution of the Maya." He also "brought in convicts for labor, making the place essentially a penal colony."

The formal end

After the Mexican Revolution, General Bravo was removed from his command and General Salvador Alvarado was made the new Governor and Military Commander of Yucatán and Quintana Roo. The Yucatan Times reports that Alvarado instituted several new reforms to address Maya grievances and released many prisoners.

In 1915, the formal end of the war was declared after some Maya groups signed a peace treaty offered by Alvarado. After the signing of the peace treaty, Alvarado "ordered all non-Maya people to leave Santa Cruz and moved the territorial capital to Payo Obispo." However, according to "The Caste War of Yucatán" by Nelson A. Reed, although the Cruzo'ob Maya were able to return to Chan Santa Cruz, their "homecoming was not happy" upon seeing what their town had been turned into. In response, the railway cars and the barracks were burned, the railway tracks were torn up, and the telegraph line was cut. Regardless of whatever peace agreements had been made, the Cruzo'ob Maya wanted to ensure that the Mexican government couldn't easily interfere. The final death toll at this point is also unclear.

The isolation was relatively short-lived and in 1917, Maya leader Francisco May agreed to "rebuild the Santa Cruz to Vigia Chico line with Maya labor," according to "A World History of Railway Cultures." Some of the more radical Maya came to see him as a traitor and in 1929, they left Chan Santa Cruz.

Continued Mayan resistance

Throughout the first few decades of the 20th century, some groups of Maya people continued to engage in guerrilla warfare against the Mexican government. In some places, "non-Maya people risked being killed if they ventured into the forest." One of the largest factions was known as the Cruzo'ob of Xcacal and was led by Evaristo Zuluub, writes The Yucatan Times, but there were several hamlets and groups that didn't recognize Mexican law.

In April 1933, two battalions of the Mexican Army went to arrest Zuluub in the village of Dzula. Although Zuluub escaped, five Maya people and two Mexican soldiers died during the attempted arrest and the village ended up being burned and taken by force, according to "The Maya of the Cochuah Region," edited by Justine M. Shaw. "Some historians regard Dzula as the last battle of the Caste War," which would make the fight for Maya sovereignty in Yucatán almost a century-long endeavor.

But even throughout the 20th century, there were numerous reports of Maya who maintained the fight for sovereignty, with some reports dating to 1997. Quintana Roo also wouldn't become a Mexican state until 1974. Meanwhile, Mexican federal troops continued to visit villages up through the 1970s, if not later, as a "regular occurrence" to surveil the Maya people, staying for several hours.

Maya in Mexico today

Although the Maya war against the Mexican government ended by the mid-20th century, Maya people in Mexico continued to suffer racist discrimination and violence. In Racism against the Mayan population in Yucatan, Mexico, Juan Carlos Mijangos-Noh writes that despite laws that claim to recognize the rights of indigenous people in Mexico, few of these rights are actually upheld.

In addition to discrimination, a lack of bilingual and intercultural education, and 21st-century land grabs like the Mayan Train, Maya people are also fighting against industrial pig farming Yucatán peninsula, whose pollution disproportionately affects Maya people, according to the Center for Biological Diversity. In May 2021, the Mexican Supreme Court ruled in favor of the Mayan people of Homún and upheld the suspension of the PAPO hog farm until the trial against them is resolved.

Cultural Survival writes that Indigenous women in Mexico have also historically "experienced intimidation and threats of suspension of social programs if they did not agree to sterilization." In 2013, it was found that 27% of Indigenous women who had sought public health services were sterilized without their consent. Al Jazeera reports that in 2021, the Mexican government offered an official apology "for the terrible abuses committed by individuals and national and foreign authorities in the conquest, during three centuries of colonial domination and two centuries of an independent Mexico."