Kareem Abdul Jabbar's Scary Experience That Made Him Feel Like He Was 'Stepping Into A War Movie'

As a teenager living in Manhattan in the early 1960s, maybe it was inevitable that Kareem Abdul-Jabbar would witness racial injustice and unrest. What he did see during those formative years had a lifelong impact on him, even influencing his basketball career. He wrote in The Guardian that he's proud of his achievements in sports because they're not only proof of his hard work paying off, but they gave him a platform to shine a light on racism in the United States.

His experiences of racism didn't start until he was in middle school. He grew up in the racially integrated Dyckman housing project in Upper Manhattan where, he said in Sports Illustrated, Black and white children got along well. However, in 6th and 7th grade, his white classmates began treating him differently. Even though he was already a star basketball player in high school, he describes himself as a "loner" at school. He would go downtown to Harlem to socialize instead. That's where he stepped off the subway in July 1964 into the chaos of a protest against police brutality.

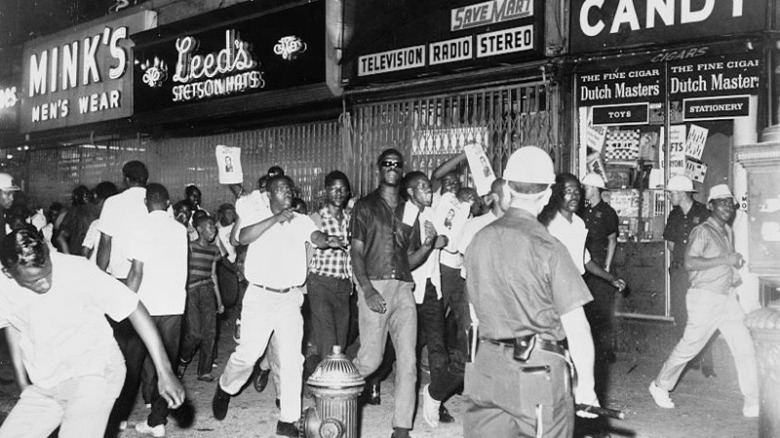

The 1964 Harlem protests

It's an all-to-familiar tale: On July 16, 1964, a white police officer shot and killed a Black teenager on East 76th Street. According to the "Encyclopedia of American Race Riots," 15-year-old James Powell and his friends were playfully rough-housing with their school building's caretaker. When they attempted to chase the man, police officer Thomas Gilligan shot Powell twice. Per The North Star, Gilligan was off-duty at the time. He claimed Powell threatened him with a knife. There were around a dozen witnesses to Powell's death in addition to his friends.

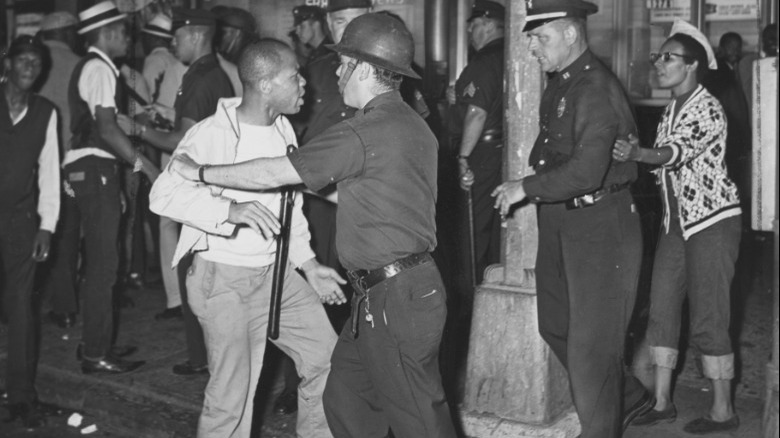

Two days later, the Congress of Racial Equality held a rally at 125th Street and Seventh Avenue. It was originally planned as a protest of the disappearance of three civil rights activists in Mississippi, but it became a protest of police brutality and Powell's death instead. As tensions rose, protesters began damaging and stealing from local businesses. 500 police officers were called to the area and blocked it off, but the unrest continued, and it would last six days, even spreading to the Bedford-Stuyvesant neighborhood of Brooklyn. By the end of the protests, one person had been killed, 118 injured, and 465 arrested (via "Encyclopedia of American Race Riots").

Abdul-Jabbar's experience of the protests

Abdul-Jabbar was 17 in the summer of 1964, and he was on his way to the library when he got caught up in the protests instead, he told NPR. He had just gotten off the subway at the 125th Street Harlem stop and emerged into what he called a "whirlpool of violence," per Black Entertainment Television. He said the scene was "chaos, wild, insane" and like a "war movie," according to Sports Illustrated.

He said the police "dismissed" the protesters' outrage, telling them to go home, to which they replied, "We are home!" He also saw the police committing violence against the protesters and was terrified he'd be shot himself, because at 7'1" he was an easy target, standing out above the crowd (via The Columbus Dispatch). He left the area as quickly as possible.

In the aftermath, he covered the protests for a youth newspaper run by Harlem Youth Opportunities Unlimited. The interviews he conducted made it clear to him that "a whole lot of innocent people had been beaten up and shot at by the police because they were black," he wrote (via The North Star).

The incident's impact on him

Abdul-Jabbar later said, "I was reborn in Harlem in the summer of '64," (via The North Star). What he'd seen and heard there stayed with him forever. In Sports Illustrated, he said it left him enormously angry, and he recognized that same anger in the protesters, who he said had chosen to get hurt rather than continue to take abuse. He wrote that he understood the protesters' impulse to destroy things to express their anger, but recognized it did no good. He was disappointed, nonetheless, that the media focused on this destruction rather than the "powerlessness" the protesters felt (via The North Star).

In Sports Illustrated, he explained the experience inspired his later activism. He started sharing his opinions more freely, and fighting injustice became more important to him than basketball. He said, "When you see people being murdered and beaten, it makes you angry. It makes you want to effect change" (via Black Entertainment Television).

Abdul-Jabbar on racism in America

One of Abdul-Jabbar's first public acts of protest was his refusal to play for the American Olympic basketball team in the 1968 Olympic Games. He explained his decision, saying, "Yes, I owe an obligation to my country, but my country also owes an obligation to me as a Black man, an obligation that has not been fulfilled for 400 years" (via The North Star).

Fighting racism, he says, is a lifelong struggle for Black Americans. Many turn to violence, in his opinion, because fighting the "right" way doesn't get them anywhere. That's how he explained the George Floyd protests in a Los Angeles Times article. "African Americans have been living in a burning building for many years... Racism in America is like dust in the air," he wrote. It's everywhere, choking people, but it's hard to see unless you shine a light on it. Black people are "pushed to the edge... Because they want to live. To breathe."

His early awareness of racism came from seemingly little things like having to go to another neighborhood for a haircut. He explained in Sports Illustrated that Black American children often learn about racial issues this way, a little bit at a time.

Abdul-Jabbar's support of other athletes

Over the years, time and time again, Abdul-Jabbar has expressed his support for other Black athletes who protest injustice. As far back as 1967, he participated in the Cleveland Summit to assess Muhammad Ali's claim to be a conscientious objector against the Vietnam War, and he fully supported Ali, who he says has been one of his greatest mentors. He describes athletes like Ali, Tommie Smith, and John Carlos as having been "silenced" by the white establishment for having spoken out against racism or other social issues. These athletes are considered "ungrateful" for their success (via The Guardian).

More recently, he's defended the national anthem protests by Colin Kaepernick and other NFL players. He told NPR he thinks more people supported Kaepernick than were willing to say so out loud. Still, he wrote in The Guardian that he's encouraged by other athletes' willingness to risk their careers to stand up for what they feel is right.