The Biggest Romanov Family Myths

If you're looking for a particularly cinematic royal family, you can't go wrong with the Romanovs. From the first to take power — Michael I in 1613, per History – to the death of the last tsar in 1918, the various members of the line have made their place in history for reasons both good and bad. With more than 300 years of continuous rule, it would be hard not to have a few standouts, like the empire-building Peter the Great or the tragic Nicholas II.

While the true stories of this dynasty are already pretty gripping, people simply can't help themselves: Alongside the very real facts of the Romanovs, a bevy of rumors sprung up. They include tales of conspiracy theories, hidden identities, and torrid love affairs. Unless you're already a scholar of Russian history, chances are you might even believe some of these stories are true if you've ever heard of them. But while a few of these most famous of the Romanov family myths might make for a great movie or a dramatic novel, the reality of what happened is far different — and perhaps far more interesting.

Myth: Peter the Great was a noble reformer

Peter the Great was a modernizer. As Britannica notes, his childhood was marked by political instability that kept him away from the center of imperial power. Yet, his quasi-exile meant he was exposed to foreign ways and skipped out on the conservative world of the Romanov court. When he finally came to power, Peter set about making connections with other nations and enacting reforms, from upsetting the rule of gentry known as the boyars, to establishing the nation's first serious navy.

But was Peter truly a ruler of the Enlightenment? Sure, he sapped the power of the boyars, but did so by becoming an autocrat who wasn't interested in others' opinions. Anyone who resisted could face serious consequences: Per Britannica, when Peter ruled that everyone should shave their old-school beards and ditch traditional Russian clothing, he took it upon himself to chop off both the facial hair and long garb of resistant boyars.

He was also a terrible father. History reports that his heir, Alexei, was shy and sickly. After Alexei's mother was kicked out of court, their relationship became even more complicated. In 1715, Peter wrote that he wanted Alexei out of the succession. Alexei agreed, then fled to Austria. That worked for a while, but Peter persuaded Alexei to return home. Then Peter put his own son on trial and had him whipped so brutally that the heir died of his wounds on July 7, 1718.

Myth: Catherine the Great was a raunchy ruler

While technically Catherine the Great started her time in the Russian Empire as a foreign interloper — per Britannica, she was born Princess Sophie of Anhalt-Zerbst in what's now Germany — she eventually became more of a renowned Russian ruler than her Romanov husband, the rather disappointing Peter III. Through her children, Catherine became further entrenched in the family line.

Moreover, the myths swirling around her are some of the wildest in the entire Romanov dynasty. According to History, she took what Peter the Great had started decades earlier and continued Russia's rise as a serious global power. But her high profile and serious power were just too much for some people to handle, and so the rumors started. The most pernicious ones have to do with her love life, which was admittedly extramarital after her marriage to Peter III fizzled. Indeed, after she overthrew Peter and took power in 1762, she kept all of her lovers far away from the marriage altar, despite the appearance of at least one illegitimate child.

Yet she didn't exactly have a parade of assignations, as the tales would have it. Instead, Catherine appears to have gone through about 12 men from 1752 until her death in 1796. It's no case of long-term sweethearts, sure, but neither is there evidence for uncountable salacious incidents. The fact that some of these rumors came from unfriendly nations and jealous fellow rulers hardly bolsters them, either.

Myth: Peter III was assassinated on his wife's order

Tsar Peter III could never get it together during his six-month reign (via Britannica). He managed to set Russia up for a war with Denmark and offended church fathers by pushing foreign Lutheran practices. He was also reportedly immature and annoying. And that was about it — for some players, it may have been a relief when his wife Catherine staged a coup and had Peter imprisoned in an out-of-the-way village.

Then, Peter died. According to Robert K. Massie in "Catherine the Great: Portrait of a Woman," the official cause of death was a stroke caused by sudden illness. He may have also been inadvertently killed in a fight with one of his captors, Alexei Orlov — who happened to be the brother of the newly-minted empress' lover and fellow coup organizer, Grigory. Or was the troublesome Peter assassinated at his discontented wife's order?

As Massie writes in "Catherine the Great," there's no evidence that Catherine directly called for her husband's death, yet he would always present a problem while alive. It could be that the conspirators who were keeping an eye on Peter read the writing on the wall, and arranged for his convenient demise. Peter was still an issue after his death: Later, Emelyan Pugachev claimed to be Peter and raised a rebellion. The New York Times reports that Catherine managed to quell the uprising, but at a serious cost to her independence after she appealed to power-hungry nobles for help.

Myth: Catherine the Great was an enlightened ruler

Perhaps we can turn to Catherine the Great for a less morally fraught example of an enlightened Russian ruler. The Collector notes that she was involved in increasing Russia's reach in the world, while she was also interested in improving domestic industry and giving more attention to education and the arts. She even championed smallpox vaccination when many were highly skeptical of its purpose.

Yet her reforms have a spotty record and include tense relations with China, alongside haphazard implementation of economic controls and administrative consolidation (meant in part to keep contentious peasants from biting back). And like her predecessor, Peter the Great, Catherine simply couldn't hand over all of the power to either politicians or the common folk, leading some to call her a despot.

These failures to bring about a glittering Russian Enlightenment shouldn't all be laid at Catherine's feet, however. Getting laws passed by political bodies like the far more conservative Legislative Commission was a task (via History Extra). Furthermore, as The New York Times reports, any populist tendencies Catherine held were likely dampened by peasant rebellions, and the realization that she needed the support of aristocrats to keep both her throne and — if the example of the French monarchy was any example — her head.

Myth: Catherine the Great died in an embarrassing way

Amongst the seriously naughty rumors about Catherine the Great was one that was both shocking and embarrassing. As the myth goes, via History, an elderly Catherine was getting very friendly with a stallion, courtesy of a custom harness. When the contraption suddenly broke, Catherine was killed.

You may have some obvious questions about anatomy and Catherine's advanced age that already made this story highly doubtful. Moreover, it's just too convenient a piece of fuel for those libelous rumors going around Europe, which maintained that Catherine (and, by extension, all powerful women) was a sexually voracious and unnatural monster. Simply put, there's no evidence that Catherine wanted anything to do with horses beyond the normal equestrian activities that all nobles did.

And, no, there's no proof that Catherine died on the toilet like an 18th-century Russian Elvis, either. According to History, we do know that the 67-year-old empress had a stroke in the bathroom in November 1796. But she wasn't on the can and instead was found collapsed on the floor. She died a day later in the respectable location of her bed.

Myth: Alexander I faked his death

Alexander I led an eventful life. He was emperor of Russia, he'd crossed paths with Napoleon Bonaparte, then took part in the Napoleonic Wars. Towards the end of his life, he became increasingly religious and began to privately speak of abdicating. While touring Crimea, Alexander contracted an unknown disease (possibly pneumonia) and died on December 1, 1825 (via Britannica).

The tsar's growing religiosity, disillusionment, and sudden death helped produce one wild myth. As related in Donald J. Raleigh and Akhmen Ikenderov's "The Emperors and Empresses of Russia: Rediscovering the Romanovs," soon after Alexander's death, people began to allege that he had actually faked his demise. Some said that he was hiding in Palestine, while others conjured a romantic image of the tsar mounting his horse and riding off for parts unknown. But the most persistent tale maintains that Alexander fled to Siberia and became the holy man Feodor Kuzmich. Per the Hemitary, Kuzmich first appears in the historical record in 1836, when he was arrested and sent off to exile. He became known as exceptionally wise, learned, and pious, as well as for his incongruous stories about the royal court. Otherwise, he lived a simple life and died in 1864.

But how likely is it that the tsar himself went undetected for decades as a Siberian hermit? It seems far more likely that Alexander simply died instead of enacting a complicated escape and second life. But that hardly makes for a good story, and so the fantastical and probably untrue story of a tsar's faked death lives on.

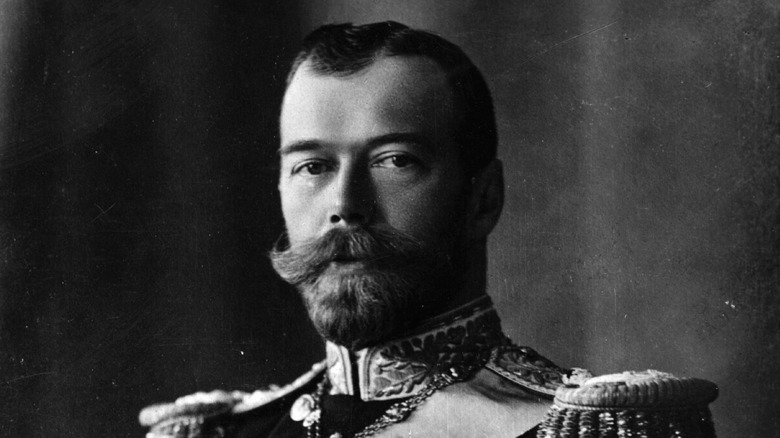

Myth: Nicholas II was a humane ruler

Some stories hold that Nicholas II was a kind ruler and loving family man who only wanted the best for everyone. As PBS reports, there's little doubt that he loved his wife, Alexandra, and their five children. But his record as a paterfamilias-in-standing for all of Russia was far more spotty.

You could have started by asking any Russian Jew. The first Nicholas I, who ruled from 1825 to 1855, was broadly conservative and specifically hostile to Jewish people. According to the Jewish Virtual Library, he went so far as to have Jewish children taken and educated away from their families, among other edicts. Like his namesake as well as his father, Alexander III, Nicholas II was profoundly anti-Semitic. Through maintaining anti-Jewish laws and tacitly approving of increasingly violent pogroms against Jewish people, Nicholas allowed vicious and sometimes seriously bloody campaigns against innocent people to continue in his empire. It was an especially damning sign of his inability to think beyond the upper-class, Orthodox environment in which he was raised.

He also contributed to unrest when he bungled major military campaigns like the Russo-Japanese War of 1904-1905 and an uprising that earned the name of Bloody Sunday. Nicholas could never quite bring himself to be a decisive leader, though he also believed he was placed on the throne through divine providence. He also failed to connect with common Russians and often tried to ignore political and social unrest, per the British Library.

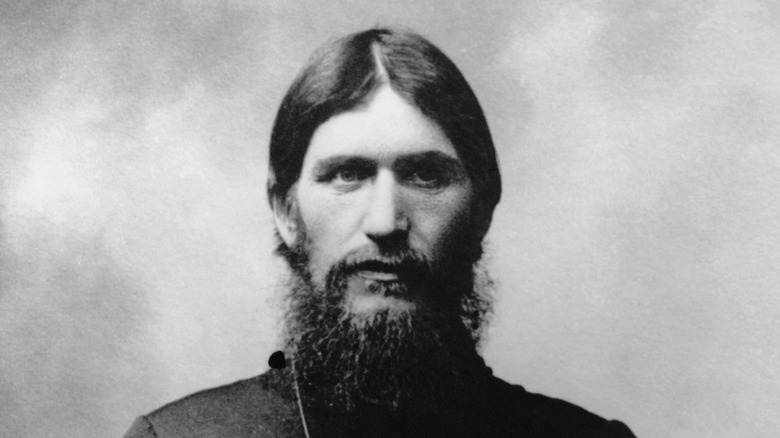

Myth: The empress Alexandra had an affair with Rasputin

At the center of the Romanov downfall was one supremely odd figure: a disheveled, rude, and intensely charismatic peasant from Siberia known as Rasputin. Having emerged from the north as a sort of unsanctioned mystic and miracle worker, Rasputin made his way to St. Petersburg. After endearing himself to the upper classes, he found an in with the royal family, and by 1908, he had apparently stopped a medical emergency that had struck the hemophiliac heir, Alexei. He gained a powerful position as a confidante and advisor for years, though his licentious ways didn't jive with the rather more prudish, Victorian household of the Romanovs (via Britannica).

Rasputin's rarely explained connection to the royal family raised many eyebrows: What was this dirty, raunchy man doing alongside the tsar and tsarina? Could it be that his widely-purported powers of persuasion had torn Alexandra away from her husband and into a torrid love affair?

Not so fast. It may make for a gripping story, but historian Douglas Smith told Town & Country that it's all nonsense. Besides the complete lack of evidence for such a relationship, an affair between Rasputin and the empress makes no sense. Alexandra was fairly repressed, at least by Rasputin's standards, being committed to her monogamous marriage and all. After all, it's worth remembering that the buttoned-up Queen Victoria was her grandmother (via Royal Collection Trust). Instead, it was likely a politically fueled rumor meant to demean an unpopular foreign empress.

Myth: Rasputin had total control over the Romanovs

If Rasputin wasn't carrying on a torrid affair with the tsarina, then at least he was a political puppet master pulling all of the strings of state. Right?

There's no doubt that some people thought Rasputin wielded far too much power, given that he was assassinated by a group of upper-class Russians on December 30, 1916. According to Smithsonian Magazine, he clearly made an impression on the royal family when he helped the young heir Alexei's hemophilia improve — perhaps by scaring off doctors who gave the boy blood-thinning aspirin, then considered something of a wonder drug. Maybe he had the ear of the tsar on an issue or two, but the fact that Nicholas barreled forward with his own policies after Rasputin's death points to the fact that the tsar was capable of coming up with ill-considered plans all on his own.

Still, there is a bit of truth to this myth. Per History Extra, Rasputin did use his pull with the Romanovs to get choice appointments for friends and squeeze money out of others. But though politically fueled rumors held that this wild peasant man was the true power behind the throne, there's no clear evidence that he was actually setting policy or directing military strategy.

Myth: Anastasia survived her family's murder

The Romanov dynasty came to an ignoble end in a house in Yekaterinburg on July 6, 1918, when Nicholas II, his wife Alexandra, son Alexei, and daughters Olga, Tatiana, Maria, and Anastasia were gunned down by Bolshevik revolutionaries. According to History, the family had been detained after Nicholas had embarked on a series of disastrous ventures that included undermining the Duma, a representative legislature, and getting Russia caught up in World War I. It all came to a head in March 1917, when the populist Bolsheviks led by Vladimir Lenin took over and forced the tsar to abdicate. The royal family was imprisoned, but their continued existence proved to be nerve-wracking for the revolutionaries.

One particularly beloved tale maintained that the youngest Romanov daughter, Anastasia, had made it out alive. The rumors gained extra fuel in the 1920s, when a woman named Anna Anderson claimed to be Anastasia. Per History Extra, plenty of others stepped forward as Anastasia, but Anderson proved to be the most persistent. A German court finally ruled that her story was unprovable in 1970 (via Britannica).

In 1991, Discover reports, a geologist admitted that he had uncovered remains he believed were those of the Romanovs. The skeletons he found in 1979 were kept secret, as the Soviets weren't keen on discussing the old royal family. Later genetic testing proved that the remains found in two unmarked graves belonged to the Romanovs, including Anastasia.

Myth: Anyone from the core royal family survived the Russian Revolution

Could anyone else have made it out of that bloody basement in Yekaterinburg? As Robert K. Massie writes in "The Romanovs: The Final Chapter," the decades after 1918 were lousy with Romanov impersonators. Various people came forward to proclaim that they were or had known an escaped Romanov — typically one of the imperial daughters or the heir Alexei himself. One man, Michael Goleniewski, loudly proclaimed that he was Alexei and also a Soviet spy. He defected to the U.S. and worked for the CIA, but proved to be an embarrassment and was effectively fired by the agency in 1964 (via The Guardian).

But then they found the family's bodies. Per The Guardian, the first set of remains was found in the 1970s and publicized in 1991. Two more individuals were uncovered nearby in 2007. Using DNA testing, researchers confirmed that these were the remains of Nicholas, Alexandra, their five children, and four servants (via PLoS One).

While the central royal family and quite a few of their close relatives had been killed, some relations survived. Per The New York Times, about 35 escaped, some with the help of cousin King George V of England. According to the National Post, Nicholas' other sister, Olga Alexandrovna, first fled to Denmark after the Bolsheviks took power. The rise of the Soviets pushed her and her family to cross the Atlantic and settle in Ontario, where Olga died in 1960.