The Tragic Wrongful Conviction Of Melvin Lee Reynolds

There is perhaps no crime more horrific than the murder of a child. Predators who stalk and prey upon the most vulnerable in our world are the most vicious and dangerous killers, taking away a community's innocence along with the young lives that they end. But imagine being innocent and the primary suspect in this type of case. The damage to your reputation and social standing, the potential loss of employment, and the shattered relationships you've spent your entire life fostering are now dangling by a thin thread over a chasm of uncertainty. But perhaps the fear of being sent to prison for the rest of your life, or even facing the execution chamber, will weigh more on your mind.

Now imagine that you've been questioned multiple times by investigators, who seem to get more relentless every time you've presented yourself. Try to feel the heat in the small room they've ushered you into and hear the intensity in their voices as they tell you over and over again that you are the person that is responsible for a crime. Put yourself in the position of an innocent person who has just been told that it will all go away if you'd only admit to the crime. After nearly 14 hours of this kind of questioning, some people might be prone to give a false confession. Compounding one particular case from Missouri in 1979 was the fact that the prime suspect was mildly intellectually disabled (per the Los Angeles Times).

The murder of a child in a small Missouri city

Melvin Lee Reynolds was 24 years old when police first questioned him for a brutal murder in northwest Missouri (per the University of Michigan). In June 1978, a 6-year-old boy had disappeared from a playground in downtown Saint Joseph, Missouri. After an exhaustive search, the body of the young boy was found in a wooded area along the riverfront that served as the city's western boundary. He had been sexually assaulted before his assailant strangled him to death (per Serial Killer Calendar).

Police interviewed scores of people in hopes to bring the monster in the community's midst to justice. From their investigation, they were able to piece together eyewitness descriptions of a man the murdered child was last seen with. The University of Michigan's National Registry of Exonerations reports that a boy fitting the victim's description was seen walking with an older man with gray hair. This might have helped police narrow down suspects a bit, but they needed something more solid to work with.

They seemingly got the break that they needed when an anonymous tip was given to them that gave them a familiar name. The tipster maintained that they had seen Reynolds lurking near the area where the victim was last seen. Reynolds had been rumored to have sexually assaulted his nephew, though this was steadfastly denied by Reynolds and his family. Nonetheless, police honed in on Reynolds, and he was soon their primary suspect.

If you or anyone you know has been a victim of sexual assault, help is available. Visit the Rape, Abuse & Incest National Network website or contact RAINN's National Helpline at 1-800-656-HOPE (4673).

Reynolds is subjected to multiple interrogations

Melvin Lee Reynolds did not fit the description of the suspect the police were looking for. He was young, not old. He had brown hair, not gray. And he was a lot shorter than the man witnesses described seeing the victim with (per the University of Michigan). Despite this, Reynolds aroused enough suspicion among investigators that he was brought into the station on many occasions and grilled about the murder.

Reynolds was interrogated nine times by police. He was also given a battery of tests over the better course of a year during those long periods of being on the hot seat at police headquarters. He was administered a polygraph test during one session. Another time, he was hypnotized. What might have cinched it for investigators was when they gave Reynolds sodium amytal during one round of intense questioning (per the Los Angeles Times). Known as "truth serum," police were probably hoping that this would finally get the words they needed to hear out of their suspect. And they got them. Sort of. Under the influence of this drug, Reynolds was asked about what he was doing the day of the murder. He misspoke, saying words that would be the first step to cementing his doom: "Before I killed — before I went to the unemployment office," he began, giving detectives what they believed was the makings of a confession. But they needed more from Reynolds before they had enough to charge him.

A final interrogation leads to charges

Melvin Lee Reynolds was brought in for questioning a final time on February 14, 1979 (per the University of Michigan). In a session that lasted more than 12 hours, investigators finally wore the man down. After hours and hours of threats and the promise that he could leave the police station if he admitted to the murder, Reynolds relented to their demands. Journalist and author Terry Ganey wrote in his 2017 book "Innocent Blood: A True Story of Obsession and Serial Murder" (per Journal of Intellectual & Developmental Disability) that "Reynolds finally looked up like a dog with his ears pressed against his head and said, 'I'll say so if you want me to."

It didn't matter that Reynolds didn't even come close to fitting the eyewitness description of the suspect. It didn't matter that he gave inaccurate descriptions of the crime scene or that a neighbor of Reynolds provided an alibi at the time of the victim's abduction. All that mattered to police, and later to a jury, was that Reynolds gave a recorded confession to the murder and sexual assault of a 6-year-old boy.

Reynolds was booked and charged with murder. After a four-day trial in October 1979, Reynolds was found guilty and sentenced to life in prison. He would later say that because of the publicity of the case — and the barbaric crime at the center of it — that his family was forced to move from the city out of fear of retribution from angry townsfolk.

If you or anyone you know has been a victim of sexual assault, help is available. Visit the Rape, Abuse & Incest National Network website or contact RAINN's National Helpline at 1-800-656-HOPE (4673).

The real killer is unmasked

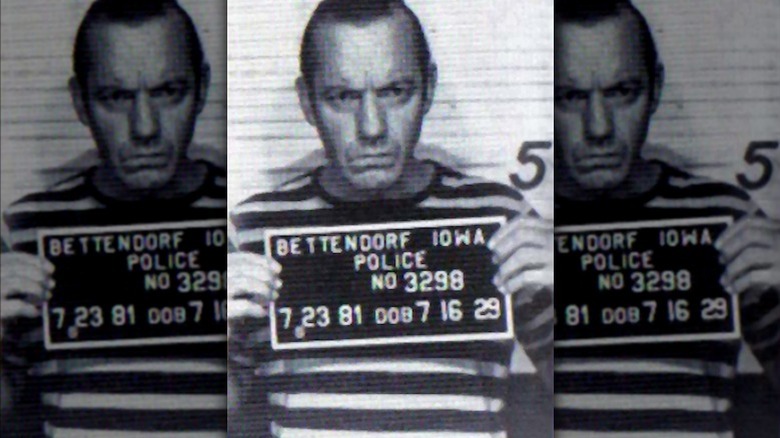

Fast forward to 1982. While Melvin Lee Reynolds was rotting in a prison cell for a murder he didn't commit, a young girl disappeared from the shopping mall in St. Joseph (via UPI). Her body was also found near the Missouri River, not far from where the 1978 victim was found. Clues would lead police to arrest Charles Hatcher (above) for the girl's murder. According to the University of Michigan, Hatcher wrote the FBI a letter while in jail awaiting his murder trial. In that letter, Hatcher confessed to the 1978 murder. A look at Hatcher was a match for the description of the suspect seen with the young boy. Hatcher also gave accurate details of the crime scene.

It took until October 1983, but Reynolds was at last ordered released from prison by a judge (per UPI). Hatcher pled guilty to murder and was sentenced to 50 years in prison. He claimed to be responsible for several other murders aside from the two young victims in Saint Joseph. His map of a crime scene eventually led police to find the remains of one victim, 28-year-old James Churchill of Lewiston, Illinois.

If you or anyone you know has been a victim of sexual assault, help is available. Visit the Rape, Abuse & Incest National Network website or contact RAINN's National Helpline at 1-800-656-HOPE (4673).

Reynolds died more than a decade ago, but is still remembered

Melvin Lee Reynolds died May 15, 2012, still a resident of Saint Joseph (via The Saint Joseph News-Press). His obituary is a brief read, giving no mention of the hardships he faced or his wrongful incarceration. But perhaps one line in the tribute to Reynolds sums up what anyone would need to know about him: "Melvin was a very kind person and he liked everyone." Simple, brief, but meaningful.

As for Charles Hatcher, he didn't live long after his conviction. UPI reports that a prison guard at the Missouri State Penitentiary in Jefferson City found him hanging from a makeshift noose made from electrical wiring attached to a ventilation duct. The death penalty that he requested but was denied by the jury mattered not, as Hatcher took it upon himself to serve as his own executioner — rather than live the rest of his life in a segregated prison unit.

If you or anyone you know is having suicidal thoughts, please call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline by dialing 988 or by calling 1-800-273-TALK (8255).