The Shady Side Of Police Psychology And False Confessions

Humanity's search for a method by which to tell if someone is lying is nothing new. "Inquisitors in ancient China asked suspected liars to put rice in their mouths to see if they were salivating," claims MIT Technology Review. "The Gesta Romanorum, a medieval anthology of moral fables, tells the story of a soldier who had his clerk measure his wife's pulse to figure out if she was being unfaithful." As technology has advanced, systems through which deception might be detected have come to the fore.

The most famous of these, the polygraph test, or lie detector, measures a combination of heart rate, breath rate, blood pressure, and perspiration, according to Wired. It's been used extensively by police and other official bodies in the US and beyond for more than a century. In addition to police interrogations, "the FBI gives a polygraph test to every single person who's considered for a job there. When the DEA, CIA, and other agencies are taken into account, about 70,000 people a year submit to polygraphs while seeking security clearances and jobs with the federal government," reports Vox.

There is, however, one flaw to the polygraph: There is no convincing evidence, even today, that the technology works, according to a recent report published by the National Academies Press. With an estimated 2.5 million screenings in America each year — many of them serving as evidence in court, per Technology Review — the continued use of the polygraph remains a baffling oversight in the fight for improved policing.

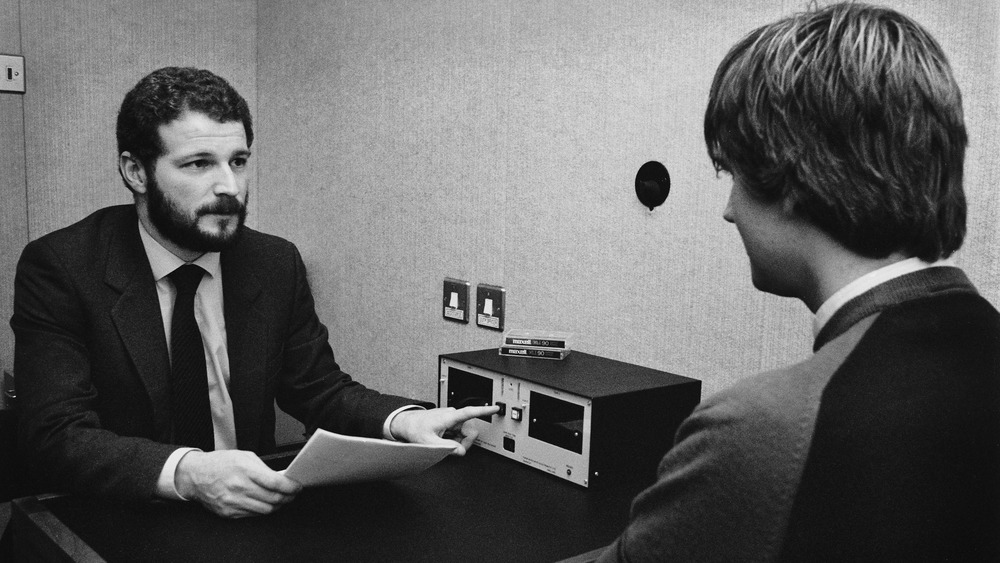

Interrogation and the 'Reid technique'

And it is not the only one where psychological evaluation is concerned. As noted by Frontline, polygraph tests often go hand in hand with police interrogations of suspects, with officers often telling suspects that they have failed the "poly" — even when they haven't.

Lying to suspects with the intention of extracting a confession is, surprisingly, an accepted practice in most American police forces, according to the same source, which cites the "Reid technique," developed by John E. Reid and formalized in the 1962 book Criminal Interrogations and Confessions, an interrogative method that involves pressuring and coercing suspects to elicit a desired confession.

Richard Leo, associate professor of law at the University of San Francisco, told Frontline: "Most of what police do in interrogations ... is legal: the accusations, yelling; moving in closer, invading one's space; lying about evidence, making it up, pretending to have evidence; telling somebody they failed a polygraph, for example." Most of us are familiar with hardball interrogation techniques from movies and television, but what isn't so widely publicized is the fact that such methods may often lead to false confessions — which then come to play a decisive part in a suspect's subsequent conviction.

"A steadily increasing tide of literature has documented the existence and causes of false confession as well as the link between false confession and wrongful conviction of the innocent," states a 2009 report published in the Journal of Psychiatry & Law, with disturbing repercussions for the moral case for such police methods.

The shocking reality of false confessions

In his interview with Frontline, Richard Leo addresses those outside the criminal justice system who assume that giving a false confession is close to impossible. Leo claims: "most people say, 'You couldn't make me confess no matter what you did psychologically,' especially to a serious crime, a rape, a murder. But most people don't know what it's like to be interrogated. Everyone has a breaking point." Leo argues that the task of police interrogators is undermined by the fact that specialists in the field are trained to make assumptions concerning the suspect's guilt — though a trial has yet to take place, the interrogator works on the belief that the suspect is guilty. The only goal is to extract a confession, in any form.

According to Science, "false confessions are not rare: More than a quarter of the 365 people exonerated in recent decades by the nonprofit Innocence Project had confessed to their alleged crime ... standard interrogation techniques combine psychological pressures and escape hatches that can easily cause an innocent person to confess ... young people are particularly vulnerable to confessing, especially when stressed, tired, or traumatized."

The same article explains how modern DNA technology, which is challenging many aspects of policing, including the re-opening of long unsolved crimes and bringing criminals such as the Golden State Killer to justice, is helping to undo the damage of such dubious police methods. For many of its victims, however, the struggle for true justice continues.