The List Of 'Endangered' Elements Is Growing Thanks To Mobile Phone Production

Let's play a little game, shall we? Have a look at that thing in your hand that you're using to read this article: your cell phone. If you're using your laptop or desktop, then just reach over and snag your phone — we know it's not too far. Pick it up, turn it over, push a button or tap the screen. And then ask yourself: Is this thing made from plastic? Metal? Some kind of synthetic blend? Is the screen glass? Some polymer thing? How does the phone even work? You might say circuits, microchips, and little wires. Fantastic, but that's pretty vague. What is your cell phone made from, really? What material elements mined from what part of Earth and composed in what factory, and where?

Such questions aren't new in and of themselves, or unique to phones. While some readers might be quick to raise their hand and rifle off a factoid suitable to "Jeopardy!," let's be honest: not too many people know the depths of how most things work, or how they're made. Cell phones take the prize, however, out of sheer numbers produced. Statista shows us that from 2007 (the first year of the iPhone) to 2015, global cell phone sales rose from 122 million to 1.5 billion, and have stayed there ever since. The chief materials? As Statista again cites, it's (top to bottom): silicon, plastic, iron, aluminum, copper, lead, zinc, tin, and so on. And how many of those materials are renewable? Absolutely none.

Star stuff in the palm of your hand

So how non-renewable are non-renewable cell phone parts, you ask? As the Independent says, we've got to think in terms of the periodic table, that thing you might have forgotten about since high school chemistry. We've got 90 natural elements to work with, including familiar ones like oxygen that we inhale into our lungs, and less familiar ones like vanadium which sounds like the name of an alien planet.

A full 30 of those elements go into making even only one cell phone, including copper, gold, silver, lithium, cobalt, and "rare earth elements" that you've probably never heard of like yttrium, terbium, and dysprosium. Many of these elements are already "endangered," and could run out completely within 100 years. This includes components needed for a phone's outer shell, wiring, battery, and so on.

As for how non-renewable these elements are, consider that trees along the equator usually regrow in 10 to 20 years, per The Environmentor. Trees in colder climates might take up to 120 years to regrow. Oil and gas? They all took 60 million years to form, per Planete Energies. Elements like iron? Iron formed nearly 1.8 billion years ago in Earth's crust, per Anglo American. Iron also forms inside the core of red giant stars that go supernova and spread their material throughout the cosmos, as Sciencing says. In other words: that phone you're going to eventually chuck? It just might house irreplaceable fragments of dead stars.

Green gold, toxic goo, and the unrecycled

Oh great, you might be thinking. We've got another environmental issue to deal with? Yes, we do; Earth taketh as it giveth. And make no mistake, we humans taketh quite a bit. A poll conducted by our sister site, SlashGear, found that out of 631 people, 11.8% of them get a new phone every single year — likely hardcore brand fans. Meanwhile, as CNET points out, it makes little sense to trade in a fully functional, expensive device even every two years because changes to models are growing evermore minimal. Is FOMO behind such rapid consumer consumption? Is it good old planned obsolescence, or the driving force behind mass market-produced, throwaway goods to make customers spend and spend, as Kem-Laurin Kramer describes in the book "User Experience in the Age of Sustainability" (via Science Direct)?

Rabid consumer consumption becomes more troublesome when considering how little the public recycles cell phones. As far back as 2008 — one year after the launch of the first iPhone — The New York Times reported soon-to-be recycled cell phones tossed into an alchemical hell of smelters and searing fumes. Conveyor belts feed shattered wreckages of phone parts into pits of molten sludge where base materials get separated like an early industrial, late-19th-century horror. Among other things, such processes produce bars of recycled, "green" gold, as well as toxic waste. And yet, 99% to 99.5% of all resultant materials are reusable, which is excellent. New Tech Recycling says that "virtually 100%" of all cell phones are recyclable, which is even more excellent. And yet, only 15% of all phones get recycled.

The new periodic table and less waste

So how do we avoid depleting yet another precious resource that we can never get back? The most obvious answer, as the Independent points out and the reader could guess: don't buy phones so often. If anyone balks at this suggestion, then go for it — it's your bank account. Plus, as soon as all the endangered elements are gone, folks will have no choice but to clutch whatever they've got because there'll be no more new phones, ever. Be prepared for some economic and social upheaval at that point, and also for big tech names like Apple and Google to lose more than a bit of their annual, phone-shoveling luster (provided they exist at all by that time). Governments could always mandate the recycling of irreplaceable goods, but looking at their general laissez-faire approach to the laissez-faire capitalism spearheading the rampant consumption of other non-renewable resources like oil, we wouldn't count on it.

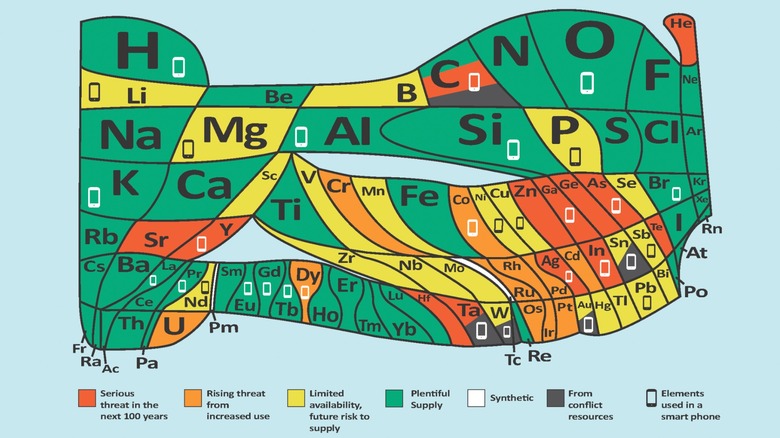

In the meantime, the Independent describes how researchers have drafted a new version of the tried-and-true periodic table in order to raise awareness of endangered elements. The new version, created by the European Chemical Society (EuChemS) in conjunction with 160,000 chemists from 40-plus chemistry-related fields, categorizes elements according to scarcities like orange ("rising threat from increased use") or green ("plentiful supply"). It even highlights elements garnered from politically-troubled world zones. It represents the first update to the periodic table in 150 years, one suitable for the modern age.