Whatever Happened To The Scientists Of Operation Paperclip?

On the surface, the story of the end of World War II seems pretty straightforward. You know, the invasion of Normandy and D-Day, the Allied forces beating back the Axis powers, the end of the Holocaust and the eventual surrender of Nazi Germany — all of that. It's a rather well-known story, one that seems like your old-fashioned narrative of good triumphing over evil.

But when you look at the wider historical context, things get a little more confusing and considerably less clear on the moral front. After all, the Cold War was looming on the horizon, and for Western powers, the Soviet Union was already a threat to be monitored and a very active factor in grand designs for the coming world order. When you also take into consideration news of Nazi Germany's technological and scientific advancements during the war, well, you end up with Operation Paperclip.

In short, Operation Paperclip was the post-World War II program to poach Nazi scientists and relocate them to the United States, often by any means necessary. If you think that sounds sketchy, you'd be right. The whole thing was thoroughly covered up, and the eventual paths those scientists' lives took were both surprising and entirely unsurprising at the same time. Here's what happened to the scientists of Operation Paperclip.

The Osenberg List

While the journeys of these Nazi scientists entered strange territory after the end of World War II, their path toward Operation Paperclip really got started right in the middle of the war. More specifically, that start came with a man named Werner Osenberg.

According to Annie Jacobsen's "Operation Paperclip: The Secret Intelligence Program That Brought Nazi Scientists to America," Osenberg was a devout member of the Nazi Party — an SS member, at that — when he was tasked in 1943 to put together an exhaustive list of the best scientific minds Germany had to offer. These individuals were to be recalled from the front lines and instead employed by the Nazi Party more directly, granting them research and testing facilities so they could improve and develop weapons. Osenberg did quite the thorough job, identifying thousands of scientists for this purpose.

But once the Allies began to invade Germany, that thoroughness backfired spectacularly. While investigating at Bonn University, soldiers noticed professors attempting to destroy a bunch of documents. After they were tipped off by a Polish lab technician, Allied forces found documents that had been partially flushed down a toilet. Not only did those records contain the names of scientists on the Osenberg List, but they also led soldiers to Osenberg's office, where they found a treasure trove of information on exactly who these scientists were and what projects they were working on. It was clear enough just how valuable that information could be.

Scientists were relocated to keep them away from the Soviets

It's pretty hard to ignore the fact that the Cold War came right on the heels of World War II, and Eastern and Western nations were already sizing each other up by the mid-1940s. As it turns out, Operation Paperclip is emblematic of those exact international tensions. Per "Operation Paperclip," a lot of the hesitation to recruit Nazi scientists evaporated in the minds of American officials once the Soviet Union became more of an active threat. Despite any initial doubts, it suddenly seemed a whole lot more important to make sure those scientists weren't left out in the open for the Soviets to snatch up themselves.

As explained by History Collection, those scientists and their families were moved around quite a bit at the end of the war. Many were held in a city called Landshut, though certain high-priority individuals were officially taken into custody — unofficially, it was so they could get to work more quickly and be incapable of emigrating to, say, Soviet Russia.

After the war ended, there were more relocations. With the Americans and Soviets slicing up Germany into respective areas they could influence, nearly 2,000 people were ordered to pack up their things immediately and head for the train station, where they could be resettled into newly appointed American zones. There, the scientists were kept effectively under house arrest, regularly checking in with military police so that their locations were known at all times.

Fighting the Soviets wasn't the initial idea

Given the context of World War II and the Cold War, it makes sense that the reason behind Operation Paperclip would've been the threat posed by the Soviet Union. But in actuality, the goals and intentions behind this secret program evolved over the course of a few years. Starting with the discovery of the Osenberg List, it's true that American forces were looking for information on Nazi science, but that was the extent of it (via History Collection). They were looking for notes and research when they scoured Bonn University — not the scientists themselves. The discovery of the Osenberg List was really something of a happy accident for the Americans.

Even then, the Soviets weren't the first thought on the minds of U.S. officials. Rather, that first concern was the Pacific. By the time of the discovery of the Osenberg List, the Pacific front was still active, and recruiting Nazi scientists sure seemed like a good way to buff up any potential technological advantage. In fact, the war in the Pacific was the reason behind initial recruitment being as quick as it was.

And there was one other part of this, too: Keep your enemies close. These were Nazi scientists; no one could trust them, which was exactly the reason they should be recruited. Bringing those scientists to the U.S. gave American officials the perfect way to keep an eye on them, rather than allowing them to roam and potentially sow further chaos (via "Operation Paperclip").

Nazi ties were covered up

If you've been thinking that this entire thing sounds morally and legally questionable, you would be correct. When this whole idea was first conceived, President Harry Truman had exactly the hesitations that you'd hope for regarding allowing Nazis into the U.S. Despite allowing the operation to exist, Truman did so with a specific caveat; according to History, he explicitly said that no active members of the Nazi Party were to be recruited.

That caused some problems for the powers behind Operation Paperclip. A good few of the scientists were SS members or had received awards from the Nazi Party (via "Operation Paperclip"); their active participation was hard to debate. So rather than tell the truth and potentially lose the valuable knowledge these scientists could bring to the U.S., they just lied. They erased participation in the Nazi Party (and war crimes) from the records of the scientists, thus allowing them entry to the U.S.

Things didn't stop there. When a particular scientist seemed to present a more difficult case, a paperclip was attached to their records — a secret signal that those files wouldn't be shown yet to the higher-ups. (It was also the inspiration for the name "Operation Paperclip," as it had been called "Operation Overcast" up to that point.) And what's more? They changed the wording of Truman's caveat. It wasn't "active Nazis" who weren't allowed, but rather those who would "plan for the resurgence of German military potential." You can probably see just what the workaround there was.

The scientists got away scot-free

Given the place that World War II and the Holocaust occupies in the general understanding of history, you'd think that, even with all the shady actions taken by the U.S. government, these Nazi scientists would've seen some sort of consequence for their actions, right? It only seems fair to think that the world wasn't keen on just letting the Nazis go and live happy lives.

But that's basically what happened with the scientists of Operation Paperclip, generally speaking, both in the eyes of the public and the government. In fact, most of the time, these scientists had to face little to no punishment for their actions. On the contrary, many were treated favorably. In her book "Operation Paperclip," Annie Jacobsen makes mention of Nazi doctor Theodor Benzinger and his rather glowing obituary in The New York Times. The article mentions the fact that he did wartime research, but neglects to say just which side that research benefitted. Instead, it shines a spotlight on his advances in the chemical and medical fields.

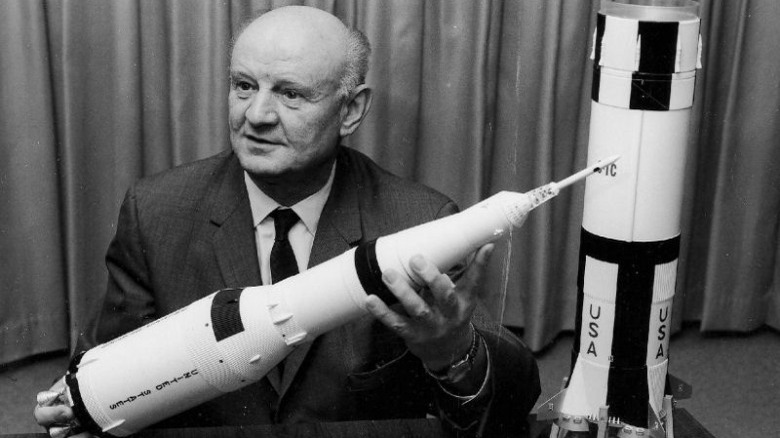

Then there are cases like Arthur L. Rudolph (pictured above), a Nazi who ran a munitions factory during the war and was brought over to the U.S. in 1945. According to The Telegraph, the Justice Department bent over backwards in 1949 to ensure there would be no problems with Rudolph gaining re-entry after visiting Mexico, claiming that doing so was in the national interest.

Many were employed at NASA

While there were well over 1,000 scientists who were tapped by Operation Paperclip, there are some pretty clear trends. One of those trends? NASA.

As summarized by History Collection, many Nazi engineers had been of interest to the Third Reich due to their knowledge of rockets. But after the war, what more natural use for rockets was there than space travel? Engineers such as Bernhard Tessmann and Kurt Debus worked on the V-2 rocket program back in Germany, with Debus being an especially staunch supporter of the Nazi regime. Nonetheless, Tessmann came to work at the Marshall Space Flight Center to research thrust control (and later created a music scholarship at the University of Alabama). Debus, meanwhile, was a central figure in the early space program at Cape Canaveral and went on to become the first director of the Kennedy Space Center, per NASA.

But not all of the scientists who worked at NASA were known for rockets. Hubertus Strughold was said to be implicated in human experimentation at Dachau, but nonetheless, he was brought over to the U.S. in 1947, per an article in Aviation, Space, and Environmental Medicine. From there, he was known for pioneering space medicine, essentially the study of what the conditions of space would do to the human body from both a biological and a psychological standpoint. That research led to the development of equipment such as early space suits worn by American astronauts, as well as understanding the effects of weightlessness on those astronauts.

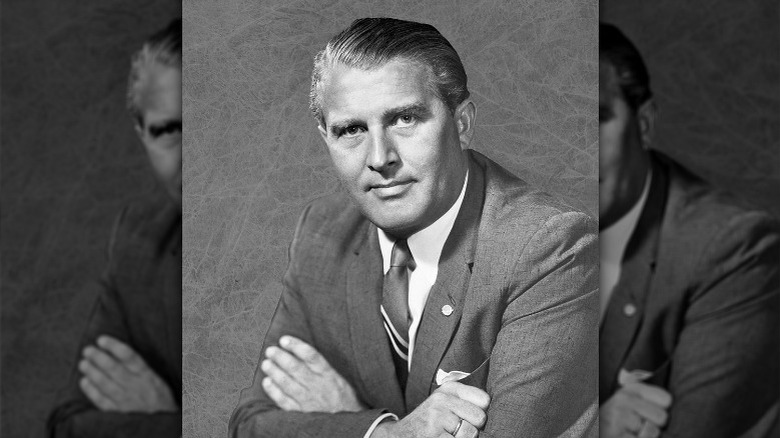

Wernher Von Braun

Regarded by History Collection as the "Father of American Rocketry," Wernher von Braun might be the best example of just how few consequences these Nazi scientists had to endure after taking part in Operation Paperclip. After all, Braun had been a high-ranking member of the SS and reportedly played a large role in the creation of harsh and cruel conditions for workers who were enslaved and forced to build German V-2 rockets.

But even sources like Britannica give little voice to his actual participation in the Nazi Party, summarizing his claims that he only did it to further his research and serve his country. Instead, his push for space exploration is highlighted, as is his major role in the development and success of the American space program. Not only was he part of the team to launch the first U.S. satellite, but he was later appointed the director of the Marshall Space Flight Center, where he headed up the development of rockets for the famous Saturn space program. He remained in positions of leadership for years and even received numerous awards from the U.S. government for his work.

Oh, and even wilder? According to "Operation Paperclip," Braun was even contacted by Walt Disney Studios in the mid-1950s and invited to appear on one of their TV broadcasts. More than 40 million people watched that particular program, ranking it among the most highly rated shows at the time. He basically became something of a celebrity.

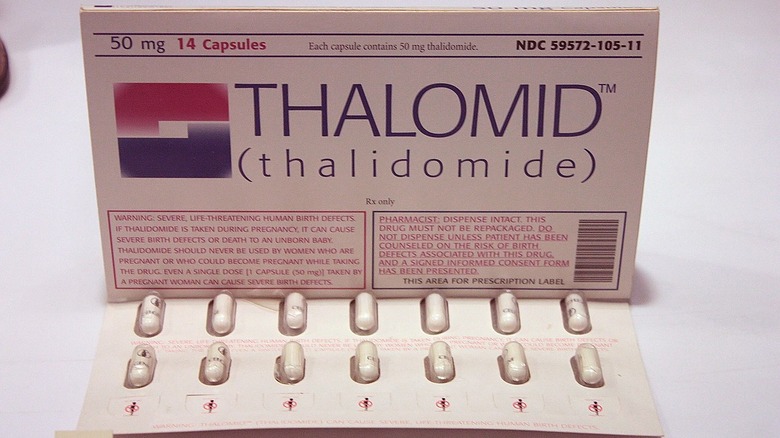

The Thalidomide Scandal

If you haven't heard of the Thalidomide Scandal, here's the rundown. Per Newsweek, throughout the 1950s and 1960s, thousands of babies were born with various birth defects — shortened or missing limbs, blindness, deafness, deformed spines, and damaged internal organs. Ultimately, the common factor was a chemical then hailed as a miracle drug: thalidomide. It was sold as a way to treat morning sickness, but when the promises of safety proved to be lies, the company responsible, Chemie Grünenthal, came under fire.

Now, where does this tie into Nazi scientists? It's deeply connected, in fact. Many of the scientists and chemists employed at Chemie Grünenthal were wanted Nazis and known war criminals. And as for where Operation Paperclip plays into this? That would be a specific man: Otto Ambros.

Ambros was a brilliant and charismatic chemist, even favored by Adolf Hitler himself. During World War II, he was responsible for the development of dangerous nerve gasses and was reported to have tested those gasses on personnel at none other than the Auschwitz death camp (via "Operation Paperclip"). Ambros was also linked to reports of mass murder and enslavement. He was found guilty during the Nuremberg Trials and sentenced to eight years in prison, but he was tapped for Operation Paperclip in late 1951 and shortly released. He would work at both Dow Chemical and even the U.S. Army Chemical Corps during the Cold War and served on the advisory committee of Chemie Grünenthal at the time of the Thalidomide Scandal.

[Featured image by Stephencdickson via Wikimedia Commons | cropped and scaled | CC BY-SA 4.0]

The Dachau Trials and deportation

When it comes to war crimes committed by Nazis, you may be familiar with the Nuremberg Trials, but they weren't the only case of Nazis being brought to justice. Per the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, from June 1945 to December 1947, the U.S. Army held its own set of trials, known as the Dachau Trials. Generally speaking, these trials existed to deal with lesser war crimes, such as cases involving lower-level guards and police members who had committed crimes against Allied soldiers. But they also dealt with bigger cases where large groups of people were harmed or killed; those cases did sometimes involve higher-level officials and SS members who were working at concentration camps such as Dachau.

According to History Collection, those trials targeted one of the scientists of Operation Paperclip: Georg Rickhey. During the war, Rickhey had been in charge of large-scale projects and production lines, many of which were built inside underground bunkers (via "Operation Paperclip"). It was said he'd even been the mind behind Adolf Hitler's personal fortified bunker, and the U.S. brought him stateside for that expertise. But when testimony at the Dachau Trials revealed he'd made use of slave labor and promoted horrendous working conditions, he was arrested, returned to Germany, and tried. Despite being acquitted in late 1947, he remained in Germany, never returning to the U.S.

The Office of Special Investigations

As disheartening as it is to learn about the lies and deceptions used to help grant American citizenship to literal Nazis. fear not — the charade didn't last forever. As documented by the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, the Justice Department's Office of Special Investigations (or the OSI, for short) was formed in 1979 with the explicit purpose of investigating cases regarding Nazis and their war crimes. They were looking for those who were not only involved in persecution, but also naturalization fraud — in other words, the sort of methods used by Operation Paperclip. According to a 2008 report, only one Operation Paperclip scientist, Arthur Rudolph, was prosecuted by the OSI, but the group still made an impact. All told, they deported and denaturalized more than 100 such war criminals and stopped a few hundred more from gaining entry to the U.S. In 2010, they merged with another group but still pursued the same goals they started with: shedding light on crimes that might have been forgotten by the public.

And speaking of the public? While Operation Paperclip was conducted under the radar, it couldn't stay that way. According to The Telegraph, in 2006, the OSI specifically looked into cases of the U.S. government helping war criminals gain American citizenship. They wrote up a 600-page report on what they found, but the Justice Department tried to hide it, claiming that none of the findings should be considered official and that many were, instead, faulty. Nonetheless, by 2010, that report leaked to the public, who were finally able to see the true scope of Operation Paperclip.