The 1988 Gladbeck Hostage Crisis Haunts Germany To This Day. Here's The Story

One reason conspiracy theories about a secret cabal controlling the world are so prevalent is that it can be far more appealing to view the world as being controlled by someone, even if their motives are nefarious than to believe that events truly are as chaotic as they appear. But the reality is that, sometimes, events play out on the world stage and there is only one explanation for them: incompetence. And when that is the case, the only reasonable responses are disbelief, anger, and horror that they could have been allowed to happen.

One such story occurred in August 1988, in the town of Gladbeck in North Rhine-Westphalia in former West Germany, when two men's plans to rob a bank escalated into a standoff that dominated the German media in the same way the O.J. Simpson car chase would become a major TV event in the U.S. less than a decade later. As reported by DW, the press itself came under enormous security following the events of the Gladbeck Hostage Crisis, with the head of the Deutscher Journalisten-Verband union, Michael Konken, describing the events that unfolded "the darkest hour of German journalism since the end of WWII." But the police were also criticized in the aftermath of the debacle due to their mishandling of the disaster, which arguably contributed to its bloody fallout. Here is the story.

A failed bank heist

In the early morning of August 16, 1988, the small town of Gladbeck was propelled into the news after it was revealed that two unidentified men had entered a branch of Deutsche Bank before it was open to customers, and demanded the money in the vault. The two men were heavily armed, even for bank robbers. According to RND, though the men were carrying only a pistol each, they had also brought with them 350 rounds of live ammunition, meaning that any confrontation with the police, who had begun to assemble outside the bank, could easily develop into a long and dangerous shootout.

Per the same source, the robbery was an utter disaster. Instead of the quick smash-and-grab that the two had envisaged, the pair had crashed their motorcycle, meaning that, though they intend to go ahead with the robbery, they were without a getaway vehicle. And once the robbery began, they realized that to get into the vault, they required two keys, one of which is with the manager, who was late for work. A passerby has already seen the armed robbers and dialed the police: a standoff began, with the robbers trapped in the bank with no access to the money they demanded.

But the drama was far from over. Not only were the police now scrambling to intercept the getaway would-be bank robbers and their loot, but the stakes had grown even higher, with the revelation that the men had also taken two bank workers with them as hostages.

Robbers turned kidnappers

As the police opened up communications with the frustrated would-be bank robbers, the two parties began to discuss the criminals' demands. Quickly, the drama ramped up — to make the police know they are serious, the two men began firing inside the bank, as well as at a police officer who had made himself visible outside (per RND).

Negotiations went on for many hours, with police hoping that the criminals would soon lose their nerve, tire, and give themselves up. But it was not to be. The two were reportedly fuelled by a cocktail of alcohol and drugs which had a stimulant effect, keeping them awake, wired ... and increasingly on edge. With the safety of the bank workers paramount, the police were forced to give in to the robbers' demands, and supply them with a getaway vehicle. They also demanded a huge sum of money, which, in bizarre scenes, was delivered to the front door of the bank by a police officer wearing only his briefs, at the behest of the paranoid criminals who suspected the police of using the delivery as a trap.

But things turned even more bizarre. As the men left the vicinity of the bank with their money, weapons, and two terrified hostages in tow, they weaved slowly in and out of nearby streets with the police on their tail. And they picked up a woman: an accomplice who turned out to be the girlfriend of one of the men. They took rest stops repeatedly, but the police failed to act.

They took control of a bus

With the police unable to intervene in the robbers' getaway due to their holding of hostages, the two men and their accomplice made numerous stops on their way to Bremen in the full sight of police and a growing number of journalists. RND reports how in one unfortunate incident, the criminals even encountered a police cruiser at a gas station, but the officer was not aware of who the men were. As a result, the armed men were able to hold up the officer and relieve him of his gun and police radio, the latter of which would keep the criminals abreast of the police's plans to capture them.

The robbers were soon identified: known petter criminals by the name of Hans-Jürgen Rösner and Dieter Degowski, a pair of petty criminals in their early thirties known to the police. Rösner had recently escaped from prison, and it was his girlfriend, Marion Löblich, who had willingly gotten into the getaway car alongside the hostages. Soon after, they made their way to Bremen, 140 miles away. Rösner, who was considered the ringleader, was convinced that the getaway vehicle had been bugged or marked by the police who had supplied it to him. So they decided to escalate things further: by boarding a bus and taking 30 more hostages.

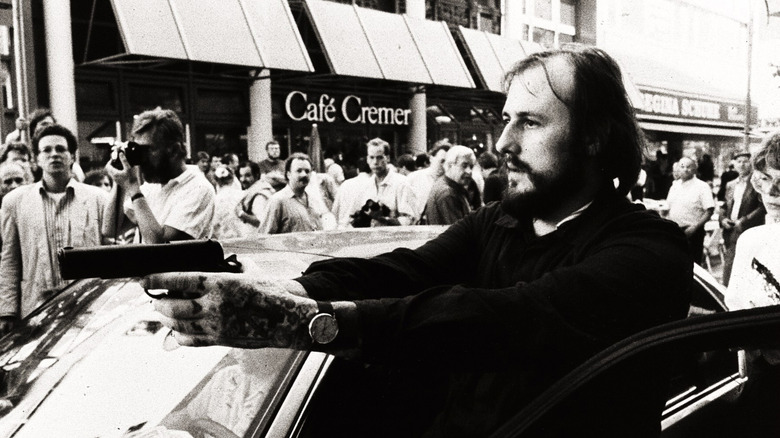

And here the hostage-takers grew even more audacious. Surrounded by police marksmen, Rösner left Degowski minding the bus while he fraternized with journalists, giving interviews and posing for photographs. And Rösner again spoke to the police, demanding a fresh getaway vehicle.

The first killing

If the criminals' willingness to be interviewed by journalists and to explain their nihilistic motives in any way painted them in a romantic light for the millions of Germans closely following the events unfold, the horrors of what then occurred on the apprehended bus in Bremen were to show in no uncertain terms what Hans-Jürgen Rösner and Dieter Degowski were capable of, per RND.

At yet another rest-stop, Marion Löblich left the bus to use the bathroom. With little planning, the police made the snap decision to capture her, perhaps hoping to use her as a bargaining chip. However, the effect of the arrest was only to enrage the wired and paranoid hostage-takers, with Rösner demanding that she was to be returned to the bus immediately or else they would begin executing hostages. The police released Löblich, but seconds before she got to the bus, a shot went off from Degowski's gun.

The victim was 15-year-old Emanuele di Giorgi, who had reportedly stepped in to protect his eight-year-old sister, whom Rösner and Degowski were threatening. Giorgi was then dragged from the bus for treatment, though responders were slow to arrive due to the entourage that was following the bus, and there was no ambulance on standby despite the obvious dangers of the situation.

The killers flee

After the horrific execution, the killers took the bus and their traumatized hostages to the Netherlands, where they traded the bus for a new getaway vehicle provided by the police. They released all but two hostages: two 18-year-old women named Silke Bischoff and Ines Voitle.

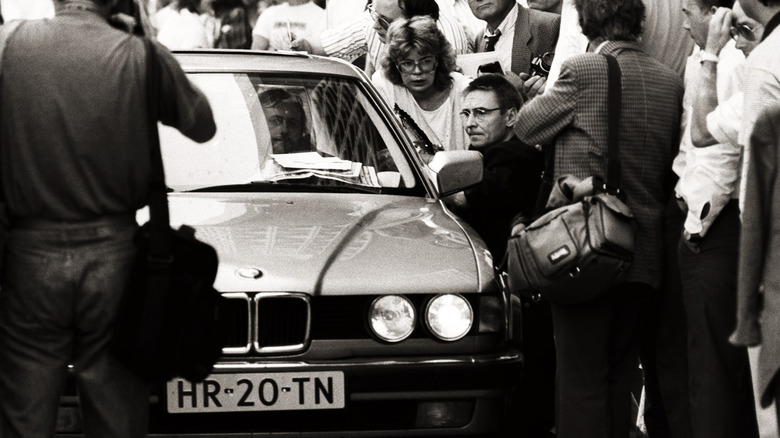

The car next emerged in Cologne, a West German city considered a media center where many news companies kept their offices. According to RND, it is believed that Hans-Jürgen Rösner was convinced that they could shake the police in the city's tight streets. But the killers — who had spent little time outside Gladbeck — instead turned their car down a pedestrianized shopping district. Per The New York Times, the car was soon recognized, after which it was surrounded by a bevy of journalists, trapping the car but also keeping the police at bay. Despite going for more than two days without sleep, Rösner and his accomplices were seemingly relaxed, while the ringleader even took the time to do some clothes shopping before talking to journalists over coffee.

But one journalist went further than most in his quest to get as close as possible to the story. Udo Röbel, deputy editor-in-chief of the Kölner Express, talked to Rösner about the possibility of releasing his current hostages in exchange for new ones. But as Rösner began to panic; he threatened the crowd with his pistol, and told Röbel to organize the removal of bollards blocking their exit. Röbel does so, after which he gets into the getaway car to give the killers directions out of the city.

The police finally struck

Udo Röbel exited the getaway vehicle after directing the criminals in the direction of Frankfurt, after which they continued on to the autobahn with their two hostages in tow, as reported by The New York Times.

With the car isolated from the wider public and in clear sight, the police took this opportunity to finally intervene. Despite the presence of the two hostages, the police rammed the car, instigating a chaotic shootout between the criminals and pursuing officers. Tragically, one of the hostages, Silke Bischoff, was shot and died at the scene, while everyone else in the car sustained minor injuries. As well as Bischoff and the earlier victim Emanuele di Giorgi, newspapers reported a third death that occurred as a result of the Gladbeck Hostage Crisis: 31-year-old Ingo Hagen, a police officer who lost his life in a traffic collision during the early part of the chase.

Rösner, Degowski, and Löblich were all arrested at the scene.

The backlash against the media and police

The immediate reaction to what had unfolded over the course of 51 hours was one of immense horror. But it wasn't just Hans-Jurgen Rösner and his small band of heartless, violent accomplices that were the targets of people's ire in the aftermath of the Gladbeck Hostage Crisis.

The police failures that run through this story go back even before the morning of the bank robbery: for a start, the runaway Rösner should have been apprehended following his escape from prison, as he returned to his hometown of Gladbeck instead of going on the lam. As The New York Times notes, the police were also criticized for failing to act earlier in the crisis, and allowing things to spiral out of control. Both of the interventions they made — the first apprehension of Marion Löblich and the later ramming of the criminals' getaway car — were separate incidents each leading to the avoidable death of a hostage.

According to the same source, the journalists involved were also widely condemned for having overstepped the mark in giving active criminals a public profile, fraternizing with them, and impeding police efforts to bring the crisis to a peaceful conclusion. Udo Röbel has shown remorse for assisting the criminals in leaving Cologne, but he has also claimed that others have interpreted his actions as having potentially prevented more violence on the streets of the city had Rösner and his accomplices been unable to escape.

The sentencing of the killers

Now in the hands of the police, Hans-Jurgen Rösner, Dieter Degowski, and Marion Löblich now faced justice for the bloody chaos they had unleashed leading to the deaths of three innocent people and traumatizing countless others. And, like the crisis itself, the sentencing of the killers was a huge media event, which dragged on longer than many had anticipated.

As reported by Welt, it took until 1991 for the criminals involved in the Gladbeck Hostage Crisis — which in Germany became known as the "Gladbeck Hostage Drama" — which emerged from nowhere to dominate the daily news in the summer of 1988.

Both Rösner and Degowski were sentenced to life imprisonment for their crimes, with the possibility of parole after 30 years behind bars, with the German legal system set up to assume that they might one day be rehabilitated back into society. Löblich was sentenced to nine years in prison for her role in assisting the two men, though she was deemed to have had lesser involvement as there was no evidence she was aware that Rösner and Degowski were planning to rob the Gladbeck Deutsche Bank.

The families took action against the police

While the police were successful in ensuring the criminals received heavy sentences for their shocking crimes, the German police force itself also came under official scrutiny for its actions that summer.

As the Associated Press reported just days after the fatal confrontation between the hostage-takers, the families of the murdered teenagers Emanuele di Giorgi and Silke Bischoff together filed charges against the German police for their mishandling of the crisis, particularly citing the police's unplanned capture of Marion Löblich as an action which irreversibly escalated the events in question. One of the lawyers involved, Gerold Bischoff, was the uncle of the latter victim.

"The charge is that of negligently causing death due to failure to give assistance," said lawyer Bernd Rosenkranz on behalf of the two families. The following November, former police officer and Minister of the Interior of Bremen Bernd Meyer resigned from his post as a result of the numerous failures of the police during the Gladbeck Hostage Crisis.

Marion Löblich was released in 1995

Details of the lives of those involved in the Gladbeck Hostage Crisis eventually emerged in the months and weeks that followed, as well as during their subsequent trial.

Marion Löblich had a difficult early life. As her backstory as reported by RND makes clear, she was brought up in poverty, and though she was apparently bright at school, she was forced into taking on a series of low-paid menial jobs to keep her family afloat during her early years. At 16, she met a man, married, and had children as soon as possible, claiming that her rush towards domesticity was her attempt to break away from her family. By the time she met Rösner, she was separated and heavily in debt.

Löblich was given early release for good behavior, serving six of the nine years to which she was sentenced, and was released in 1995, after which she returned to menial work among long stretches of unemployment.

Dieter Degowski was released in 2018

As the man who for hours on end held a pistol to the neck of teenage hostage Silki Bischoff, Dieter Degowski's face became a familiar one in the German newspapers for many months after the story of the Gladbeck Hostage Crisis first broke. In the first months of his prison sentence, many women wrote to him, with one becoming especially close. Degowski proposed, and the pair were later married and granted visitation, though they divorced soon afterward (via RND).

The image of Degowski that emerged through the trial and various press reports painted him as a self-pitying man who was in the thrall of the domineering Hans-Jurgen Rösner. After serving 30 years behind bars, he was released back into society under a new identity in 2018, with experts deeming that the murderer — who had a long history of criminal activity before the events of August 1988 — was no longer a threat to others.

Hans-Jürgen Rösner remains behind bars

Hans-Jürgen Rösner was considered the driving force behind the Gladbeck Hostage Crisis, the criminal's leader who was willing to speak to journalists, make demands of the police, and threaten violence to get his way.

While both he and Dieter Degowski received life sentences for their roles in the events that led to three people losing their lives, Rösner's sentence was more severe. As RND notes, he was deemed to require "preventative detention," meaning that there is very little chance of his release. He has since been found guilty of drug possession while in prison, while his defiant attitude has meant that he has been allowed fewer freedoms than other prisoners.

At the time of Dieter Degowski's release from prison in 2018, Rösner publicly admitted his feelings of guilt regarding his actions in the summer of 1988, though he has yet to formally apologize to the families of his victims. The terms of his imprisonment have since been relaxed, but he remains behind bars.