The Bizarre Will And Testament Of A Michigan Tycoon Took Almost A Century To Come To Fruition

It's not uncommon to find odd stipulations when it comes to last wills and testaments. While most explain how to divide assets among remaining family members, some choose to be more creative in terms of what and how they give away their possessions. Take, for instance, billionaire Leona Helmsley, who gave $12 million to her beloved dog. Comedian Jack Benny, on the other hand, chose to continue to profess his undying love for his wife beyond the grave by stating in his will that a red rose was to be delivered to her every single day until she died (via MacMillan Estate Planning).

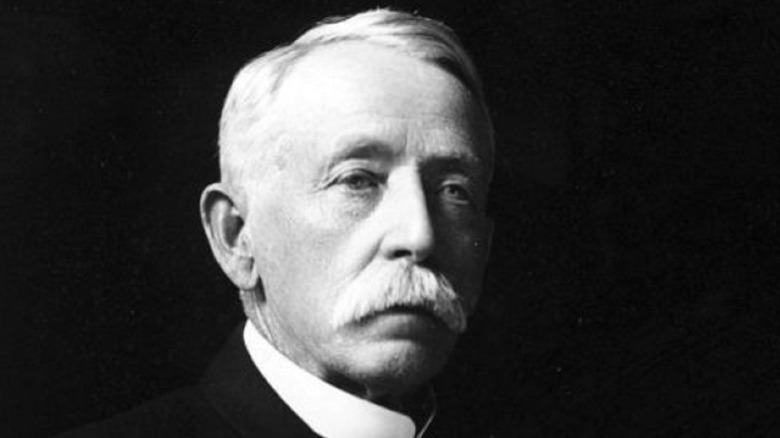

There are other wills, however, that are created out of spite, and that's just what tycoon Wellington Burt did when he formulated his final wishes. As reported by M Live, Burt was born in 1831 in New York to a farming family. They moved to Michigan when he was 7 years old, and in his early 20s, Burt traveled to different locations before settling back in his hometown when he was 26. That was when he got into the lumber business, and he worked his way to becoming a millionaire. Apart from his mill operation, he also invested in railroads. Per ABC 7, Burt was considered one of the richest men in the U.S. during his time.

Wellington Burt's net worth

Wellington Burt's (pictured right) lumber mill was built in 1864 and consisted of a factory, mills, blacksmith and carpentry shops, as well as a gas station for supplying light to the 45 houses on the property where employees lived, according to M Live. It was considered a state-of-the-art mill at that time. He owned bonds in other countries as well, and at one time, he even loaned the Bank of Montreal $6 million when it was experiencing financial difficulties. Burt reportedly lived extravagantly, donning the most expensive garbs and treating guests to 15-course meals at his mansion. However, he also gave back to the community through his philanthropic efforts.

Burt funded a high school and an auditorium in Saginaw, and he also donated to a women's hospital, a home for the elderly, and the YMCA, among others, as noted by the Saginaw County Hall of Fame. Apart from being a business mogul, he also served as the mayor of Saginaw and the senator of Michigan. Burt died in 1919 at 87 years old, and he was reportedly worth $90 million at the time of his death (per Celebrity Net Worth).

The spite clause

After Wellington Burt's death, his massive estate wasn't immediately divided among his children and grandchildren. Instead, the handwritten will had a stipulation that stated his fortune — which he referred to as the "golden egg" — was only going to be divided among his descendants 21 years after the death of his youngest grandchild who was alive during his death, as reported by Harrison Estate Law. According to some reports, it was a "spite clause" that was added because of undisclosed disagreements within the family.

Apart from the spite clause, he left between $1,000 to $5,000 to his children annually — except for his favorite son, who was given $30,000 per year. One of his daughters was supposed to be given $5,000 too, but it was retracted before his death, as he had a conflict with her about her divorce, according to M Live. Some of his employees were mentioned in the will as well; his coachman, cook, housekeeper, and chauffeur were given $1,000 each yearly, while his secretary received $4,000 yearly. Burt's family disputed the will in court, but the majority of his estate stayed intact, and the golden egg was just waiting to be distributed. That time finally came in 2011. The judge in charge of executing Burt's will told ABC 7, "I think he was a wise old man, kind of foxy. And really, I think he knew what he was doing in the long run."

The distribution of the golden egg

Wellington Burt's last grandchild at the time of his death was Marion Lansill, who died in November 1989. The countdown for the distribution of the golden egg then started. Twenty-one years later, in 2011, Burt's estate was ready to be divided among his descendants, of which he had many. However, not everyone was eligible to receive the money, and some of them died during the 21-year wait. The estate, which was reportedly valued at $110 million, was divided among 12 descendants, as noted by Harrison Estate Law. The recipients were aged between 19 to 94 years old.

Ninety-one years after Burt's death, the 12 descendants were gathered to carry out the will. The money wasn't divided equally, however, and it was distributed based on age. The lowest amount given to an individual was $2.6 million, and the highest amount was $16 million. Judge Patrick McGraw, who executed the will, told ABC 7 that he advised the recipients to figure out among themselves how to divvy up the golden egg if they didn't want to go through court appeals. All agreed to the amounts, and Burt's final wish finally came to fruition. However, the reason behind the odd will and testament still remains a mystery. "He might not have liked his kids. You could see how he gave different monies to different relatives," Judge McGraw surmised.