Tragic Details Of WWII's Bombing Of Dresden Campaign

On July 14, 1941, two months after the Blitz killed 43,000 people and dehoused many more, Winston Churchill articulated the British people's sense of vengeance, "...we will mete out to [the Germans] the measure, and more than the measure, that they have meted out to us."

Over the next four years, the Allies would certainly mete out "more than the measure" to the German people as World War II escalated. Historian Richard Overy estimates that 353,000 civilians died in attacks on Berlin, Frankfurt, Cologne, and especially Hamburg, where some 37,000 people died on July 27, 1943, during Operation Gomorrah. Hitler's architect Albert Speer said the Hamburg attack "made an extraordinary impression" on Nazi leadership and had caused him to advise Hitler that further attacks could "bring about a rapid end to the war."

However, despite the terrible raid on Hamburg, there is one place more synonymous with Allied destruction than any other in Germany: the Saxon city of Dresden. On the nights of February 13 and 14, 1945, 800 British bombers dropped 2,700 tons of explosives on Dresden, reducing it to a charred wasteland strewn with bodies and rubble. Secondary U.S. raids occurred over the next two days, pulverizing the city even further. Here are the tragic details of this WWII bombing campaign.

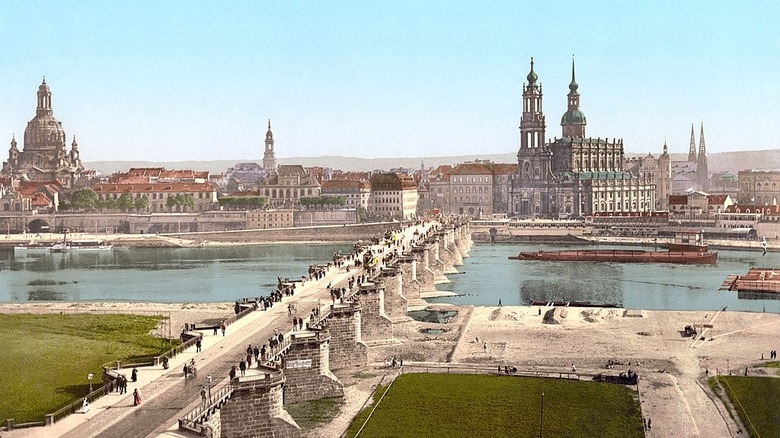

Dresden pre-bombing: a santuary from chaos

By February 1945, Germany was peering into the abyss. The Western Allies had fought their way through France, Belgium, and much of the Netherlands on their way to the Rhine river, which Patton's Third Army would cross on March 22, 1945. Meanwhile, in the east, the Soviet Union had completed the Vistula-Oder offensive, which had pushed the frontline all the way to Breslau, a city just over 150 miles away from Dresden. The German war machine was in its death throes but it could still lash out with terrible force. Hitler's offensive in the Ardennes — dubbed the "Battle of the Bulge" by American correspondent Larry Newman — killed 19,000 U.S. troops and wounded many thousands more.

Dresden was removed from this bloodshed. Several air attacks had neared its city limits, namely the American strike on Freital in August 1944 that killed 241 people, but Dresden had escaped the incessant Allied raids of 1944 that killed on average 127 people a day. Alas, luck would run out for "Florence on the Elbe."

"[Dresden was] by far the largest unbombed built-up area the enemy has got," read RAF briefing notes circulated in early 1945. Known for the fine china it produced and the value it provided the country for its many factories, Dresden became a prime target for the allies.

At least 25,000 civilians died

Accepted death toll estimates once ran into the hundreds of thousands. However, much of this consensus was informed by disgraced historian David Irving, who referenced a contemporary "Tagesbefehl 47" document that listed 202,400 registered deaths. In his book "Dresden: 13 February 1945," historian Frederick Taylor showed that these figures had been greatly exaggerated by Nazi officials for propaganda purposes.

In 2010, in an attempt to settle the death toll speculation, the Dresden Historians' Commission launched an official investigation. After a five-year project that drew on archives, cemeteries, reports, and witness testimonies, the Commission concluded that up to 25,000 people died in the attack.

The stories beyond the numbers make for harrowing reading. Survivor Lothar Metzger recounted the "cremated adults shrunk to the size of small children, pieces of arms and legs, dead people, whole families burnt to death, burning people ran to and fro, burnt coaches filled with civilian refugees." Otto Sailer-Jackson, a keeper at the city's zoo, described the elephants' "spine-chilling screams” as they were maimed and killed. "I had no choice but to leave these animals to their fate," he said.

The Dresden bombing created a huge firestorm

Like with the infamous Hamburg raid, the RAF's bombs created a firestorm so ferocious that it uprooted trees and boiled asphalt. "Everywhere we turned, the buildings were on fire," recalled Otto Griebel, a local painter (via "Dresden"). "The more we moved into the network of streets, the stronger the storm became, hurling burning scraps and objects through the air."

Nearby was 15-year-old Gerhard Kuhnemund, who glanced out of his attic window and noticed, "The whole of Dresden was an inferno! On the street people were wandering about helplessly. A house wall collapsed with a roar, burying several people in the debris. A thick cloud of dust arose and, mingling with the smoke, made it impossible to see." The inferno grew so large that only the deepest underground sanctuaries would suffice. Ordinary basements were flooded with smoke, poisoning inhabitants who were cremated when the flames reached them. "These human beings had experienced a quite gentle and peaceful death," wrote a neighbor of Günther Kannegiesser, whose mother, sister, and brother died in these circumstances. "They all lay there quite calmly and in a relaxed way, as if they had simply laid themselves down to sleep."

Those who survived were faced with a city stripped of almost everything. A government report quantified the terrible loss, with two dozen banks destroyed, a nearly equal number of insurance buildings pulverized, nearly 650 shops destroyed, and many, many more buildings that crumbled.

Refugees were among the dead

Dresden had long been treated as a sanctuary in the German heartland. Journalist Goetz Berlander, then just 18 years old, told The Guardian that the city's gauleiter had reassured citizens that their cultural city would not be targeted. This mistaken notion caused officials to send thousands of refugee children to Dresden from the eastern front, which had become a wholesale German retreat.

By February 1945, the Red Army was descending on Breslau, a city just 170 miles from Dresden. Throngs of refugees were now descending on the Saxon capital, joining a battery of Allied POWs that included author Kurt Vonnegut, who would write about his experiences of the attack. An estimated 300,000 refugees crammed themselves into Dresden's stations and public spaces. The attack, wrote Richard Overy, had "ghastly consequences" for them. Officials were effective in identifying refugee bodies and noting their causes of death, including asphyxiation, burns, suicide, and being killed by forceful impacts from the bombing.

Jewish people were also among the dead in Dresden

By 1945, Dresden's Jewish population had dropped from 6,000 to around 170. Among them was Victor Klemperer, whose marriage to Eva, an Aryan woman, had saved him from deportation and death. As recalled in "Dresden," the Klemperers survived the first wave of bombs and, despite the "terrible strong wind" that blew through their damaged "Jew house," they resolved to get some sleep. Sirens interrupted their rest no more than an hour later and panicked them into the streets, where a nearby bomb exploded and blew the couple apart. Victor survived without major injury, but Eva disappeared.

Meanwhile, in the Sporergasse neighborhood, Henny Wolff's friends were dying in a cellar. As recalled in "Dresden," "No one could get them out," Wolff remembered, "In this inferno, there were no rescue workers ... A doctor was among those buried ... we hoped that he had enough cyanide to enable them to be spared the horrors of death by suffocation."

Despite such terrible experiences, Wolff described the air raid as "our salvation," although 40 of the remaining Jewish people in Dresden died in the Allied strike. Salvation was the spirit for Victor and Eva Klemperer, too. After hours of terror, confusion, and guilt, the couple was reunited among the rubble and ashes of their oppressors. Seizing the moment, the Klemperers ripped off their yellow stars and, posing as Aryan refugees, fled southwest.

Centuries of architecture were destroyed

Dresden has long been a landmark of German and European heritage. During the 17th and 18th centuries, the Saxon capital was a prominent fixture of the Grand Tour, a cultural voyage popular among young British elites. In his book "Bomber Command," Max Hastings described Dresden as a place that "stood for all that was finest, most beautiful and cultured in Germany."

After the bombing, 2,700 tons of explosives changed all of that, gutting Dresden of its art and architecture and reducing much of the city to a smoldering pile of rubble, including the Frauenkirche, Dresden's most prized architectural jewel. The imposing 300-foot structure withstood the bombs but faltered when temperatures rose to 1000 degrees Celcius. It had taken 17 years to build the Frauenkirche in the 18th century, but when its masonry buckled 200 years later, the enormous dome crashed to the ground in mere seconds, staying there as a jarring reminder until a painstaking renovation took place from 1993 to 2005.

The cultural destruction was so great that it sent a "wave of anger" through the British establishment. As recalled in Hasting's book, even Winston Churchill expressed his concern: "The destruction of Dresden remains a serious query against the conduct of Allied bombing. I am of the opinion that military objectives must henceforward be more strictly studied."

The attack was launched in multiple waves

The first wave of bombers struck Dresden just after 10 p.m. on February 13, creating a firestorm with scores of incendiary explosives. Then, at around 1 a.m. the following morning, another wave of planes attacked the city, grounding it further into dust with high explosive bombs. In as little as 40 minutes, 13 square miles of Dresden's historic center lay ruined.

This strategy had been developed through the war. The incendiaries were dropped to cause fires before the main bombardment of high explosives, which fed the flames with strong gusts of oxygen and cleared a path for the blaze to rip through its environment. The wave formation had another, even more, sinister motive, too. The pauses between attacks were calculated to target the medics, firefighters, and other response units stemming fires and tending to casualties. Such cruel details were the reality of total war.

There may have been more effective targets than Dresden

In an interview for The World at War, a bomber veteran said, "If you couldn't get the kraut in his factory it was just as easy to knock him off in his bed ... and if granny Schicklgruber next door got the chop, that's hard luck." This philosophy may have been agreeable at the time, but some historians have doubted the effectiveness of area bombing, especially in Dresden's case. Some believe economic disruption would have been greater if the RAF attacked the suburbs, as this area contained the bulk of the city's industrial power.

The wider issue of area bombing is complex. It is true that the bombing pulled attention and resources away from the eastern front, which was where Germany suffered its greatest losses. This may be the strongest justification for the Allied bombing campaign — including the raid on Dresden — but others have specified the American oil campaign of 1944 and 1945 as more devastating to the German war effort.

The war in Europe ended just three months later

Dresden was hit far less than other German cities. Berlin, for instance, endured more than 65,000 tons of Allied bombs compared to Dresden's 7,000. However, Dresden almost got through the war without any major damage at all, as the conflict ended just 84 days later.

Was the attack necessary so late in the war? The U.S. military thought so, describing Dresden as a worthy target. Others have corroborated this view, noting the large number of military trains passing through Dresden's central station on an average day, causing the city to be a major hub of transport and communications.

However, despite this rationalization, Frederick Taylor told Der Spiegel that the viewed the attack as "overdone" and "excessive" and believed that it is "to be regretted enormously." RAF flying ace H. R. Allen went further: "The final phase of Bomber Command's operations was far and away the worst... the outrages perpetrated by the bombers will be remembered a thousand years hence."

Dresden took years to clear and many more to rebuild

The first raid lasted 15 minutes and the second only a few minutes more, but it took decades to rebuild the city of Dresden. Roughly 75,000 of the city's 220,000 homes were destroyed and they had to be cleared before they were rebuilt.

From 1945 to 1955, the view from Dresden city hall changed from a dense cityscape to a blank canvas with a skeleton of roads with nowhere to go. By the 1960s, the communist government in East Germany had erected vast housing projects but refused to restore some of Dresden's most beloved buildings, namely the ruined Frauenkirche, which authorities designated as a memorial and anti-war symbol.

The Frauenkirche was restored only after German reunification in the 1990s, but some buildings were withheld from Dresdeners for even longer. Chief among them is the Residential Palace, host to the royal apartments. Restoration began in 1997 and, after spending $350,000, the royal apartments opened to the public in 2019, 74 years after Allied bombs had destroyed them.

The bombing caused lifelong trauma

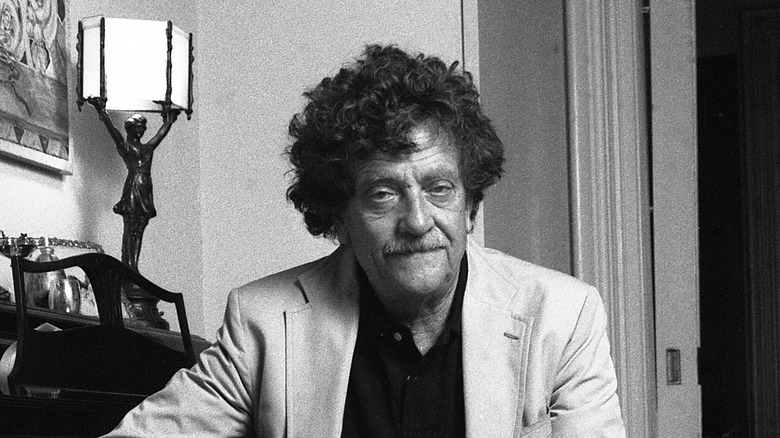

Perhaps the most famous victim of the Dresden raid is not a German but the American novelist Kurt Vonnegut, whose book "Slaughterhouse-Five" explored the misery he experienced in Dresden.

Caught during the Battle of the Bulge, Vonnegut was being processed in Dresden when his comrades rained hell on him. He and his fellow POWs were placed in an underground meat locker, where they sheltered through the night. Vonnegut described (via The New York Times) the city's remains as "like the moon now, nothing but minerals. The stones were hot. Everybody else in the neighborhood was dead." Vonnegut and his peers were forced to work in ruins, recovering bodies for funeral pyres while locals jeered and threw rocks at them. Locals' contempt for Vonnegut and his imprisoned comrades was part of a sudden hatred for the nations that had destroyed their city.

Vonnegut described Dresden in "Slaughterhouse-Five years later: "It looked a lot like Dayton, Ohio, more open spaces than Dayton has. There must be tons of human bone meal in the ground."