The Scary Reality Of Being A Journalist

A free press and the journalists behind those media outlets are essential to any democratic country. Without access to true information, citizens are unable to make the necessary choices to better their lives and guarantee the government serves the best interests of the people, not the other way around. Therefore, the healthiest democracies tend to be the ones where members of the press feel the safest to carry out their critical work.

On the other hand, because so much power can be tied to the words of journalists, those who do not want to lose control almost always see the profession as a serious threat. That fact alone makes the career incredibly dangerous in many parts of the world where authoritarians thrive, yet reporters face significant risks from several other sources as well. From crossfire in war zones to violent threats from psychopaths online, a position in news media can be exceptionally scary.

Members of the press are frequently harassed or threatened

Especially with the rise of social media, threats and harassment of journalists have increased significantly in recent years. When talking with The Washington Post, Jodie Ginsberg, president of the Committee to Protect Journalists, described the terrifying situation and said, "We've seen a huge explosion in harassment of journalists online, and unfortunately, the highest number of victims of that are female journalists."

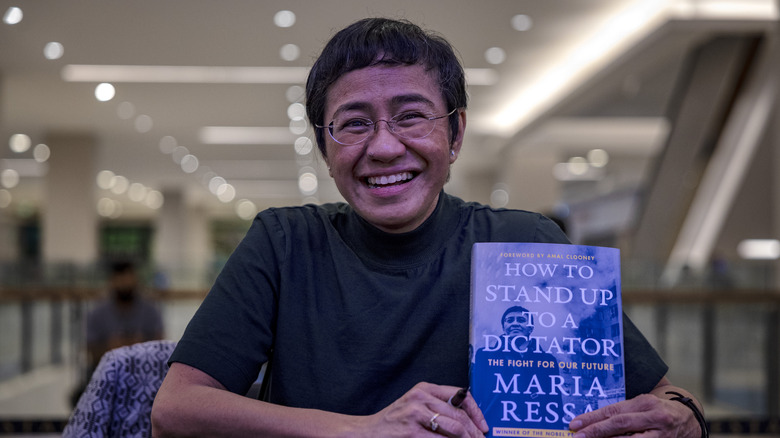

In 2017, UNESCO provided a prime example of how bad it could be for just one individual, Maria Ressa (pictured), the chief executive and co-founder of Rappler in the Philippines. On Facebook, the journalist received around 2,000 messages that were either harassing her or even threatening her life.

A growing number of media professionals have spoken out about their own scary experiences, including Bill Jaynes, editor of the Kaselehlie Press in Pohnpei. He told The Guardian, "In the 15 or so years I've been at this desk I have had several death threats." For journalist Joyce McClure who worked on a remote island in the Pacific, the fear pushed her to follow her passion elsewhere. She made the troubling admission, "Eventually, the threats to my safety were too much to handle. I spent too much time looking over my shoulder, living behind locked doors, and never going out alone after dark."

Journalists have had their property damaged or destroyed

For an alarming number of journalists, threats have escalated a step further to result in the vandalism of personal property. Even in the Pacific Island region, which is relatively safer for members of the press and the heinous crimes against them are rare, costly damage to valuable belongings like cars is far too common.

In one of the most extreme cases, an anonymous Fijian journalist not only had his vehicle broken into but was even evicted from his home simply for asking a politician questions. Afterward, he told The Guardian, "I do not see a future for me or any other journalist who is curious and questioning to make a career in journalism in Fiji." When Joyce McClure described how bad her situation had gotten, she said, "I was harassed, spat at, threatened with assassination, and warned that I was being followed. The tires on my car were slashed late one night." Likewise, Bill Jaynes had a similar experience and explained, "Some angry individual carved a request for me to perform an act of physical impossibility into the hood of my car which then rusted for posterity."

Online threats have led to real violence for female journalists

Journalism can be a scary career choice in general, but unfortunately, it can be far riskier for women than men due to an extreme level of sexism that remains in much of the world to this day. When Gharidah Farooqi of News One in Pakistan described the disturbing difference to The Washington Post, she said, "I see my male counterparts — they're also abused, but not abused for their bodies, their genital parts. If they're attacked, they're just targeted for their political views. When a woman is attacked, she's attacked about her body parts."

Even worse, the danger for female reporters increased considerably in less than 10 years. While in 2014, 23% of women reporters admitted in a survey that they received threats or intimidation online, that number rose to 73% in a more recent survey conducted in 2020, according to DW. While those numbers only represent verbal attacks on the internet, that is where a lot of journalist murders begin. In 2017, nearly half of all the victims killed in the profession were first threatened online before losing their lives. Two of the most tragic examples were the reporters Gauri Lankesh from India and Daphne Caruana Galizia of Malta.

Reporters can be assaulted in the streets

Authoritarian leaders often resort to detaining journalists they perceive as a threat to their power, yet more primitive methods are commonly used too. Several extreme incidents occurred in Uganda early in 2021 when dozens of press personnel were attacked while covering elections and protests. Amon Kayanja was one of the victims and described the frightening experience to VOA. He said, "They started beating us. We asked them why are they beating us? They were not giving us a reason. They broke my camera. The phone was destroyed. They had some sticks; they whipped us. They were chasing us away. We had nothing to do."

Journalists not only have to fear the agents of corrupt governments, but the danger of physical attacks may also come from less obvious sources like hired thugs or even angry citizens. Even when the assailants' intent is not to kill or seriously injure, the harm they dole out is no less frightening. Such was certainly the case in 2020 when three Indian reporters were not only beaten by a mob in New Delhi but were then held hostage for an hour as well until freed by police, as reported by Al Jazeera.

Insurance is not available to most journalists

Since the journalism profession can be so deadly for those operating in unstable countries with active warzones or the high possibility of terrorist attacks, such as Afghanistan and Libya, the top media outlets provide their courageous employees with several options for insurance policies. The types of coverage include medical, life, disability, and even emergency evacuation out of exceptionally lethal situations.

So, reporters from established news agencies like The Washington Post and the New York Times have some security going into the field, however, most are not so lucky. The extremely scary fact is that the majority of the press throughout the world in the continents of Asia, Africa, and Latin America do not have any access to insurance, even when covering war, as reported by Slate. The briefing, "Safety of Journalists and Media Freedom: Trends in non-EU Countries from a Human Rights Perspective," gives a description of many of these exceptionally brave professionals who are very underpaid, yet doing essential work in areas that international media cannot reach.

The threat of imprisonment is common in many countries

One of the most dangerous and all too common threats that journalists face in many parts of the world is the loss of their freedom by being thrown into prison. Disturbingly, the immoral practice of authorities to silence members of the press by locking them up has been on the rise for the past decade. In 2021 alone, there were 293 cases of journalists being imprisoned, as reported in the briefing, "Safety of Journalists and Media Freedom: Trends in non-EU Countries from a Human Rights Perspective." Additionally, another 65 reporters were taken hostage, mostly from countries with recent warzones, such as Syria, Iraq, and Yemen.

With those responsible for silencing media personnel often in control of the law, the threat of imprisonment is openly used as intimidation without remorse. When Maria Ressa recalled the moment of her controversial arrest by Philippine law enforcement to the New York Times, she said, "One agent threatened one of our reporters, telling him, 'Be silent, or you will be next.'"

Fiji is a scary example of how the legislature can target journalists with the Media Industry Development Decree. According to Reporters Without Borders, "Those who violate this law's vaguely worded provisions face up to two years in prison. The sedition laws, with penalties of up to seven years in prison, are also used to foster a climate of fear and self-censorship" (via The Guardian).

American journalists face increasing danger covering shootings

In the modern era, the U.S., like most developed countries, has been thought of as a relatively safer place to work when compared to much of the world. Yet, that belief seems to be changing, as Bruce Shapiro explained to the New York Times. The executive director of the Dart Center for Journalism and Trauma at Columbia University said, "In the past, we've thought of physical danger as something that accompanies war or high-risk investigative reporters. This is different. What we're now seeing around the country is local newsrooms feeling and experiencing more danger." He then added, "[Newsrooms] increasingly feel they need the kind of training and vigilance that you would once have assumed only those journalists venturing into hostile environments overseas."

When reporter Dylan Lyons was shot dead at a crime scene hours after the initial shooting while covering the incident in 2023, it only confirmed what many members of the press have been thinking ever since firearm-related crimes began to sharply rise across the nation. Erik Sandoval, a reporter at WKMG-TV in Orlando, said the local tragedy was a "rude awakening that danger still exists in our industry, and we have to confront that and persevere through that."

Unintentional deaths can occur on the battlefield

Warzones are extremely dangerous environments for everyone unfortunate enough to be in them, and media professionals are no exception. In a substantial amount of these cases, those reporting from the battlefield are not even specifically targeted because of their work, yet still become victims of the volatile situation. From 2002-2011, 97 journalists were slain by crossfire, and in the following decade from 2012-2021, that number has increased to 158, according to the report, "Safety of Journalists and Media Freedom: Trends in non-EU Countries from a Human Rights Perspective." On the other hand, the war-torn country of Syria is an example where these professionals have been singled out and struck down on purpose.

After Russia invaded Ukraine in 2022, the country became the most dangerous location for reporters to carry out their work. By early 2023, the number of journalists slain in the conflict had risen to 15, as reported by CNN.

Political journalism is more dangerous than war reporting

Without viewing the data, it would be safe to assume that journalists working near battlefields would face the most risk, but that is not true. Instead, it is the professionals who focus on politics that have the highest chances of losing their lives. In an interview with The Washington Post, Jodie Ginsberg explained, "The major threats come from a number of areas. One is authoritarian governments who only want to have one point of view, heard and seen. And so, they'll use all sorts of means to suppress journalists — from jailing to even supporting the killing of journalists to legal harassment." When talking with CNN, she added, "Covering politics, crime, and corruption can be equally or more deadly than covering a full-scale war."

This frightening reality is confirmed by the statistics as well. While from 2012-2021, 23.8% of journalists were killed as they reported from warzones, 28.8% of the tragic deaths occurred when politics were covered, as stated in the report, "Safety of Journalists and Media Freedom: Trends in non-EU Countries from a Human Rights Perspective."

Journalists are killed with impunity far too often

Nearly as horrifying as the murder of journalists is the fact that the terrible crimes are often done so with impunity, in which governments support the actions instead of punishing those responsible. Of the 1019 journalists killed from 2002-2021, there were absolutely no legal ramifications for nearly half of the cases, says the briefing, "Safety of Journalists and Media Freedom: Trends in non-EU Countries from a Human Rights Perspective." Even worse, nearly all of the rest had at least partial immunity.

Throughout 2012-2021, most of the slayings of reporters without repercussions occurred in the countries of Mexico, Somalia, Syria, India, Afghanistan, Iraq, Philippines, Brazil, and Pakistan. While in a place like Mexico, the murders were tied to the criminal activity of the cartels, the ongoing war has been the reason for the deaths in Syria. Regardless of the reason, the total number of killings is quite alarming at 224 in that time period.

Some journalists are tortured or brutally murdered

While there are a large number of dangerous professions throughout the world, journalism is one of the few where in some places there is a very real possibility that just doing the job can result in truly barbaric torture and murder. One of the most extreme examples occurred in 2018 with the absolutely horrific killing of Jamal Khashoggi at the Saudi consulate in Turkey. To dispose of the gruesome remains, the vile perpetrators even dismembered the body. As reported by The New York Times, the Yeni Safak account stated, "Horrendous tortures were committed on Khashoggi, who came to the consulate for documents."

Members of the press have also been brutally tortured and killed by authorities in Myanmar and Afghanistan as well. In the first country, journalist Ko Aung Kyaw survived his horrid treatment, but just barely. He told The New York Times, "In my mind, I was dead. Later, when I saw the photo they took, I didn't recognize myself. My face was swollen, and I didn't look like a human."

Another reporter, Fatema Hosseini, witnessed the utterly terrifying torture methods the Taliban used on his colleagues and described what horrors he saw to USA Today. He recalled, "They were taken to two separate cells and flogged. They were punched and lashed and hit with water pipes. They were beaten with whatever the Taliban had access to. One of them had his cheek torn, so he was being lashed right in the face, by his eyes."

The traditional journalism industry is struggling to survive

Journalists potentially face so many risks that can lead to physical harm that other threats are often overlooked. The most significant of these dangers has been the slow death of the profession due to dramatic shifts in the modern world, which has only sped up in recent years. Northwestern University reported, "Since 2005, the country has lost more than a fourth of its newspapers (2,500) and is on track to lose a third by 2025" (via The Hill). In 2022, two newspapers a week were failing in the U.S, according to the Associated Press.

While the drop from 8,891 newspapers nationwide in 2005 to 6,377 by 2022 is frightening, the situation is far worse for individual journalists who have decreased in number from 75,000 to 31,000 in that time as well. There is also much less cash to go around for salaries as revenues have plummeted from $50 billion to $21 billion for the surviving media outlets.

The nature of online media is causing long-form journalism to decrease considerably as well. Journalist Elizabeth Bruenig explained, "The question is, how do you get people to hang in with you? I know that people have a lot of options. And I'm trying to get them to read a story rather than watch a video." Senior editor Andrew Beaujon at Washingtonian expanded on the predicament and added, "[Long-form news articles] are really resource-intensive, and either they hit, or they don't. And if they don't hit, you've really blown it."