The Legend Of The 6th Century Irish Monk Who May Have Sailed To America

In elementary school, you probably learned that Columbus sailed the ocean blue and discovered America in 1492. Later, you learned that in fact, Norse explorers made it to America at least four centuries earlier. But what you don't learn is the possibility that someone else had already beaten the Norse to America 500 years before that.

Irish legend tells that a monk named St. Brendan the Navigator sailed west to a legendary land sometime in the 6th century AD, enduring sea monsters, volcanoes, and storms to reach a mythical, promised land that has been identified as everything from Africa to a metaphor for paradise. Among the more likely candidates, however, is North America.

St. Brendan's journey has evoked fascination among enthusiasts and scholars, who debate its veracity to this day. With a combination of archaeological evidence, modern-day attempts to recreate the voyage, and Norse stories about the Americas, the evidence suggests that St. Brendan's voyage should not be discarded. Here is the legend of the Irishman who may have "discovered" America.

Mobhi: The man who became Brendan

The man who would become St. Brendan was born in 484 AD in a place called Fenit in County Kerry, Ireland. Now, according to St. Brendan's Catholic Church, his name was originally Mobhi. But the Ireland of the 5th century AD was rapidly changing.

According to Prof. Elva Johnston of University College Dublin, late antique Ireland had seen the introduction of Christianity to the island via Roman Britain – most famously by people such as St. Patrick and St. Palladius. Obviously, the conversion of Ireland did not happen overnight, and instead, took place as a complex interplay and melding of the pagan and the Christian. Eventually, the religion reached Western Ireland where the young Mobhi lived with his family.

It is plausible to assume that Mobhi and his family were converts to Christianity from Celtic paganism, because when he was baptized by one Bishop Erc, his name was changed to Broenn-Finn, or in English parlance, Brendan. Finally, at the age of 26, he was ordained a priest. Armed with the zeal of a convert, St. Brendan threw himself into making converts among his people through an institution that would shape the Celtic Christianity of the British isles – monasteries.

Evangelizing the Emerald Isle one monastery at a time

The Romans never conquered Ireland, and as a result, the island was never urbanized as Roman Britain and Gaul were. There were no large cities, cathedrals, or any institutions that could reliably evangelize the population and educate it in the faith.

Thus, as St. John's Seminary notes, Ireland developed alternative infrastructure for effective evangelization. The answer was monasteries – religious communities where monks lived copying books, praying, fasting, doing penance, and most importantly educating their people in the Christian faith.

In 512, the newly minted Fr. Brendan threw himself into the monastery-building frenzy that engulfed 6th-century Ireland. Between 512 and 530 AD, St. Brendan founded two new monastic communities in Western Ireland – namely Ardfert and Shanakeel in County Cork, per The Catholic Encyclopedia. Eventually, his influence became so great that other communities were founded to propagate his spirituality, such as a remote community on the otherwise-uninhabited Blasket Islands off the coast of Kerry.

St. Brendan continued founding monasteries well into the latter half of the 6th century. He made several stops in Britain, including at the famous monastery of Iona. His most famous founding was the monastery of Clonfert in 557, where he is buried today. But it seems that somewhere in his life, he decided that his missionary zeal was going to take him West – far, far away from Ireland on a great voyage to an unknown land.

The great journey west begins

The newly-converted Irish were imbued with a missionary zeal to spread the gospel throughout Europe. Many Irish missionaries went East into Central Europe to evangelize the inhabitants of modern Germany. St. Brendan, however, wondered what and who lay beyond the shores of the Atlantic Ocean.

This great journey is preserved in the 9th-century Latin text called "The Voyage of St. Brendan the Abbot." The text narrates that a man named Fr. Barinthus came to St. Brendan and told him of a journey he undertook with one Mernoc and a handful of other monks to a place called the "Land of Promise of the Saints." Barinthus described this land as lush, green, and covered in fruits and flowers. After exploring the island for 15 days, the priest claimed that the party had reached a great river flowing from West to East. At that point, a "man, shining with great light," appeared to them and told the party to turn back. The land beyond the river was land "He [God] [would] grant unto His saints." Thus, the party returned to Ireland.

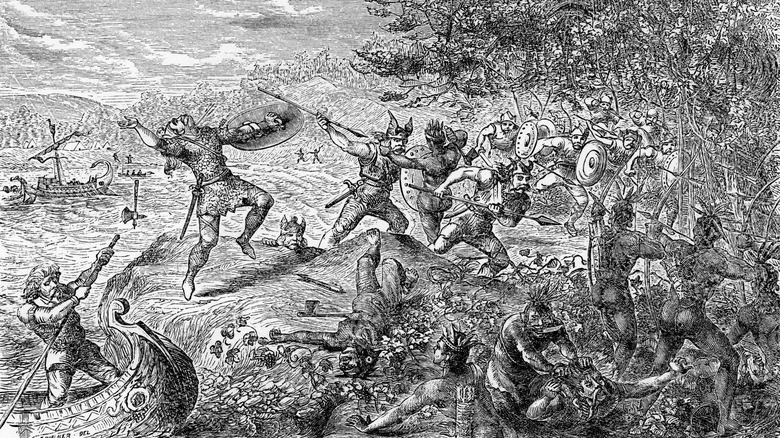

Intrigued by the story, St. Brendan chose 14 monks to search for this mystical land as Mernoc and Barinthus had done previously. But before leaving, three more monks requested to join despite warnings that they would all perish along the voyage – two of them painfully. The party then left Ireland in a small boat "covered in cow-hide" with only 40 days of provisions.

Snaking through the North Atlantic

"The Voyage of St. Brendan the Abbot" narrates that the party made many voyages rather than just one between a handful of places in the North Atlantic that can be reasonably identified today. Now, the first few years of the voyage were spent between three main places: the "Island of Sheep," the "Paradise of Birds," and the Monastery of St. Alibe, which according to historian Tim Severin,'s book "The Brendan Voyage," likely corresponded to the Faroe Islands and an Irish monastic community somewhere between Ireland and the Faroes respectively. The identification of the islands with the Faroes is supported by local tradition. There exists a place called "Brandarsvik" – Brendan's Creek in English.

Eventually, the party continued north and west, reaching an island full of volcanoes (a.k.a. a mountain with "great smoke issuing from its summit"), which given the geology of the North Atlantic, could only have been Iceland. After encountering various other dangers, including sea monsters (likely whales) and a "gryphon," the monks encountered an island inhabited by a lone Irish hermit.

On this island, whose location is unclear because of the back-and-forth voyages between Iceland, the Faroe Islands, and other places in the North Atlantic, the party encountered an Irish monk who had originally lived in the "monastery of St. Patrick," presumably a monastic community back in Ireland. He had abandoned his boat, relying on God to nourish him, but told St. Brendan that they would reach their final destination.

Landfall

Eventually, St. Brendan and his party made landfall in the Land of Promise of the Saints. The Voyage of St. Brendan the Abbot only dedicates one short chapter to the place, leaving many details that enthusiasts of pre-Columbian transatlantic contact would give an arm and a leg to know.

Nevertheless, chapter 28 says only the following: The crew sailed westward and was eventually enveloped in a great darkness. After a voice told Brendan that his goal lay beyond the darkness, they proceeded until a light shone and revealed a gorgeous land in the throes of autumn. Trees were covered with fruit and the sun never set. It seemed quite fantastical.

For 40 days, the monks crisscrossed the land until, like Barinthus and Meroc, they came to a great river. Then, a "young man of resplendent features" (probably the same as Barinthus saw) appeared to them and said that Christ had wanted St. Brendan to explore "His diverse mysteries in this immense ocean." Once St. Brendan had fulfilled God's will, only then was he allowed to set foot on this promised soil. But like Barinthus and Meroc, the angel told him that his exploration was at an end. He ordered Brendan to take stones and fruits from the land and return to Ireland. The land he had found would only be settled by God's elect once "all nations [were] under [His} subjection."

Quite a journey all in all, but the account creates more questions than it answers starting with the most obvious: was any of this possible?

What does the evidence say?

Unfortunately, it is not possible to prove with current evidence whether St. Brendan really saw what "The Voyage" claimed he saw. But it is possible to extrapolate the plausibility of such a voyage from evidence gleaned from Norse sources and archaeology. First and foremost, there is the "Landnamabok", a medieval Icelandic work known in English as the "Book of Settlement." Now, the Landnamabok claims that the Norse discovered and settled Iceland. As noted in the Icelandic Times, it was generally accepted that when the Norse arrived in Iceland, they found an island devoid of human habitation – except that the Landnamabok says that this was not the case.

In the prologue of the "Landnamabok," it reads that "before Iceland was peopled from Norway, there were in it men whom the Northmen call 'Papar.' A footnote in the text notes that "papar" means "father" in the sense of a Christian priest, no doubt related to the Latin/Italian "papa" meaning "pope." When the Norse arrived in Iceland, they found "Irish bells, books, and croziers," all signs that Iceland had hosted a population of Irish clergymen before the Norse arrived. These monks had also established themselves in the Faroes and in Orkney – right where St. Brendan landed more than once during his great voyage.

According to Dr. Kristjan Ahronson, there is now archaeological evidence in the form of cross carvings that suggests the "Landnamabok" is accurate. Thus, it seems that Irish clergy was already reaching Iceland well before the 8th century AD, suggesting that St. Brendan could definitely have gotten there in the 6th.

But was it America?

So Irish seafarers were already sailing the North Atlantic before the Norse were, but could they have reached America itself, as it seemed Barinthus, Meroc, and St. Brendan had? Again, there is no direct evidence, but it is possible to extrapolate from Norse sources whether such a journey and others like them could have happened.

Archaeologists now definitively know the Norse reached North America, establishing at least one settlement called L'Anse aux Meadows in Canada. But the "Landnamabok" mentions that the Norse were not alone in America – and it wasn't just the indigenous people they had to deal with. The Landnamabok narrates that one Ari Marsson was swept across the Atlantic to a place called "Ireland the Great." The inhabitants of this place, which was also referred to as "Whitemansland," held Ari in such high esteem that they would not let him return home. This land was located near Vinland, which is generally considered to have been someplace in North America, probably Canada.

Now, interestingly, this tale was originally told by a merchant named Hrafn, who had lived in Limerick, Ireland. He appears to originally have heard the story from local Irishmen. Now, the presence of a "Great Ireland" in America would mean that St. Brendan's voyage was at least plausible. And while it is tempting to write off the "Landnamabok" as a once-off, it is not the only possible mention of America.

The second Irish colony in America

A second potential reference to Irish in North America exists in the Eyrbyggja Saga. Here, a Norseman named Gudleif Gudlaufsson was blown off course while sailing from Ireland to Iceland. He ended up well west of Iceland – more specifically to the southwest, where he was shocked to find a colony of people who the saga claims spoke Irish. The people of this land – wherever it was – seized Gudhleif and his crew. Eventually, however, the chieftain honored Gudhleif and eventually let him return to Ireland.

So what does any of this have to do with St. Brendan? These two stories provide circumstantial evidence that St. Brendan's voyage was, on the face of things, plausible as far as the Norse texts are concerned. It is clear that regardless of whether the Irish made it to America, the Norse certainly believed they did. It also helps confirm parts of Brendan's narrative in relation to the North Atlantic.

So to recapitulate, recall how St. Brendan visited the Faroes, Iceland, and the lone hermit on some island in the Atlantic. It is known that Irish clergy settled Iceland and the Faroes, so Brendan's voyage to these areas, which forms the bulk of "The Voyage of St. Brendan the Abbot," is likely to be true. Then there is the question of the lone hermit. Is it possible that these monks pushed even further West and established communities that have been lost to time in the Western Hemisphere? Given the Norse evidence, it certainly seems plausible. But could these small Irish oxhide boats make it that far?

Tim Severin's voyage

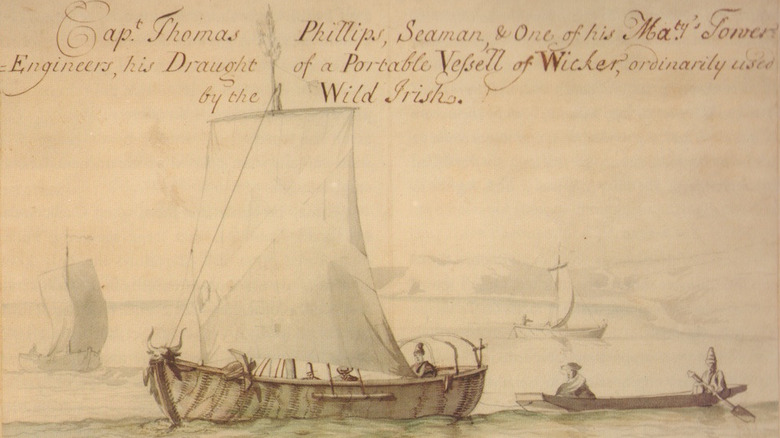

So far, the evidence shows that St. Brendan's voyages were not out of the ordinary in his time. But was a transatlantic voyage to America in a small oxhide boat possible? In 1976, sailor and historian Timothy Severin proved that it indeed was. In his book titled "The Brendan Voyage," Severin recounted how he got together a crew and built a boat called a currach (illustrated above), similar to St. Brendan's vessel. Severin's crew retraced St. Brendan's voyage to the best of their ability, sailing from Ireland up to the Faroe Islands. From there, they went to Iceland, down the coast of Greenland, and eventually reached Newfoundland. The boat that people had written off as a rickety deathtrap was actually quite sturdy.

Now, Severin did not prove that St. Brendan made the trip – he only proved it was possible. But he noted in his book that his experiences and observations were similar to St. Brendan's, especially when stripping away mythological aspects. Thus, sea monsters and giant friendly fish made sense when Severin and his crew saw whales come up to play near their boat. The mountains of fire were Icelandic volcanoes. The "pillars of crystal" were likely icebergs.

And what about America? All Severin had to say was that St. Brendan's description of his promised land bore a close resemblance to the northeastern part of America – that is New England and Eastern Canada. Again, there was no way to tell for sure, but despite all the fantastical details, "The Voyage of St. Brendan the Abbot" suddenly made sense.

Making sense of it all

So all in all, how does one make sense of these facts? The reality is that all that is available as evidence are Norse sources, Irish legends and traditions, and the heavily mythologized narrative of St. Brendan's voyage. If the story is true, it would be the oldest documented transatlantic crossing — the second oldest if the story of Meroc that inspired St. Brendan is taken seriously.

Now, the reality is that there is no definitive evidence on the ground that scholars agree upon. Some enthusiasts, including former Harvard professor Barry Fell, as recorded in the Los Angeles Times, have cited a number of carvings as evidence for Irish presence in America, arguing that these carvings represent an Old Irish alphabet called Ogam. Most scholars, on the other hand, discount these theories. Apart from this, there are disparate native traditions such as an alleged Shawnee legend recorded by Danish scholar Carl Rafn, which told of Europeans living in the southeastern United States.

So as it appears, the debate is unlikely to end anytime soon — at least not until some definitive Irish artifact from pre-Colombian America appears. But the legends should not be discounted, either. There is too much Norse evidence for that. But if they are true, it means that Columbus was just following the well-worn path of legendary Irish monks who risked everything to go out and preach the Gospel to all the nations of the world.