What The Americas Were Like Before Columbus Showed Up

October 12 marks the day that Christopher Columbus and his crew sailed the ocean blue in search of an alternate route to East Asia and India. According to Britannica, they made landfall in the Caribbean on the Bahamas. There, they encountered a rich Pacific people called the Taino, who gave Columbus much gold and inspired Spain to begin the colonization and exploration of the landmass that would eventually be called America. But was Columbus the first person to discover America? According to the Catholic Encyclopedia, German monk Adam of Bremen had recorded the continent's existence in the 11th century. And it was certainly far from the undeveloped, "virgin land" (via Digital History) that pervades American mythos to this day.

Before Columbus, the Americas were a diverse and fascinating place. From the Arctic regions of Canada to the Andes Mountains of South America, different types of state organizations developed among the linguistically and culturally diverse groups of Native Americans. Parts of the Americas built magnificent cities, produced luxury gold jewelry coveted by European conquerors, and perhaps even traded and interacted with other parts of the world. It is impossible to tell exactly what the Americas were like before Columbus arrived due to the continent's diversity. Below are some more interesting and lesser known gems and tales of pre-Columbian America.

How did it start?

The major question regarding the Americas concerns the relations of their pre-Columbian inhabitants to the rest of the world. Surely Native American languages did not pop up in situ, and the inhabitants must have migrated from somewhere else if the Out of Africa theory of human origins is accepted. The overarching theory explaining the settlement of pre-Columbian America posits that the bulk of Native Americans descend from migrations of Ice Age hunter-gatherers, who crossed the frozen Bering Strait from modern Russian into Alaska and gradually spread throughout the continent. While VOA notes that this theory is simplistic, linguistic evidence suggests that some Native Americanss do have Siberian origins.

Linguists have, in vain, tried to find links between the numerous and sometimes isolate languages of the New World and those of Asia. But in 2008, the NY Times reported that Western Washington University professor Edward Vajda may finally have found the crucial link. Vajda connected the Na-Dene languages of Western North America and Alaska (e.g. Eyak, Tlingit, Apache, and Navajo) with the Yeniseian languages of Siberia, whose only modern survivor is the Ket language. Vajda noticed similarities in the structures of the Na-Dene and Yeniseian languages, suggesting that they most likely had a common origin that went back over 12,000 years. Unlike other attempts to link Siberia and North America, Vajda's proposal has found acceptance in the linguistic community. If he is correct, it would confirm that at least some Native Americans came from Asia.

Polynesian partners?

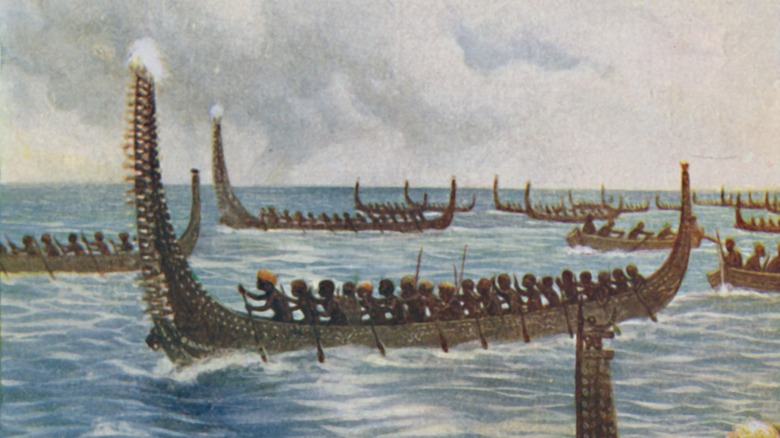

The Americas are generally considered to have been isolated from the rest of the world before 1492. But evidence from South America and the South Pacific suggests that the peoples of Columbia and Ecuador may have had contact with Polynesian seafarers who were island hopping eastward.

According to a 2013 study published in Nature, the keys to unlocking the mystery of trans-Pacific relations lay in DNA and the spread of an American holiday favorite — the sweet potato. This tuber is found in both the Americas and the South Pacific, but, according to Reuters, not anywhere else. Nature suggests that the initial spread of the sweet potato to Polynesia was the result of Polynesian seafarers visiting South America.

Smithsonian Magazine notes that Polynesian seafarers, who settled such remote locations like Hawai'i and Easter Island, were experts in their craft. They travelled thousands of miles from Pacific island to Pacific island, so there is no reason why they could not have reached the coast of South America. Now, new evidence suggests that this hypothesis is true. DNA evidence published in Nature has found pre-Columbian Native American ancestry in the inhabitants of eastern Polynesia around the 13th century. If this was indeed the case, the next question is the frequency of contact. If the hypothetical Polynesian visit to America was not a one-off isolated incident, it would suggest that the Americas were not a set of isolated continents, but part of a larger commercial system that spanned oceans.

Alaska and Asia

Further evidence for America's connections to the world at large comes, surprisingly, from the U.S. state of Alaska. Alaska was the potential arrival point for early hunter-gatherers crossing from Siberia. Evidence of contact across the Bering Sea comes from the presence of the Yupik languages on both sides of the Bering Strait, but material evidence has been thin.

Since 2010, increased archaeological work has shown that Alaska's natives likely were part of trade networks that stretched from Europe all the way to China and Siberia. Archaeologists excavating near Cape Espenberg (via LiveScience) discovered bronze artifacts that predated Columbus by at least 400 years. Since metalworking was unknown in Alaska, they could only have been traded down the line over the Bering Sea or the Pacific from China or Korea. This harmonizes with DNA evidence proposing that the Inuit are the descendants of a more recent migration from Asia.

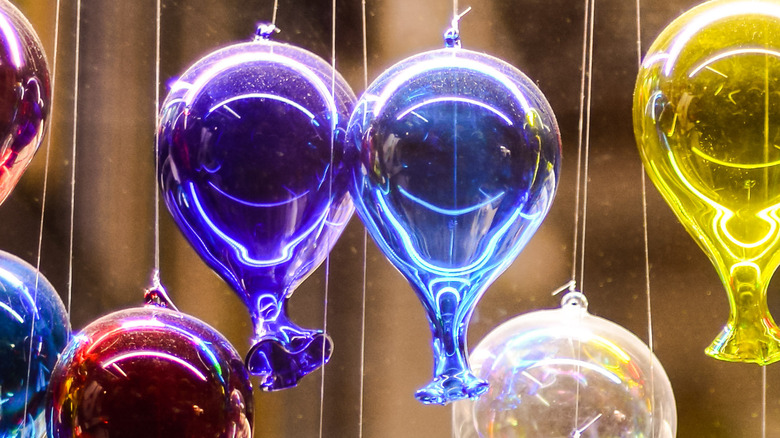

The case for an East Asian connection has found further evidence from Venetian blue glass beads in Alaska. In a study published in American Antiquity, researchers dated them to the 15th century or earlier, well before Columbus. Thus, according to UAF Fairbanks, the only way they could have arrived in Alaska was from East Asia, which imported Venetian goods over the Silk Road. These findings suggest that the Alaska natives did maintain trade contacts to obtain prestige goods that they could not produce themselves. Did Alaskan elites direct this trade, was it more spontaneous, or a bit of both? Either way, it seems the Alaska natives knew more of the world beyond than previously thought, although to what degree is unknown.

Mexico was a hotbed of civilization

Thus far, it turns out that multiple genetic inputs contributed to the population structure of the pre-Columbian Americas. There are relatively few outside influences, however, in the continent's major civilizations, which developed complex states and, eventually, empires as early as the 13th century B.C. Mexico was one of two major hotbeds of civilization in the Americas, and one of the richest parts of the New World.

The first complex civilization in the Americas was the Olmec culture, which appeared around 1200 B.C. in the Mexican state of Veracruz. According to History, numerous other civilizations followed, from the magnificent city of Teotihuacán to the Tarascans of Michoacán. But the jewel of pre-Columbian Mexican civilization came from the people who gave the country its name: the sophisticated but warlike Mexica people, more commonly known today as the Aztecs.

Originally from around the Utah-Arizona area, the Mexica (via Deseret News), according to their legends, migrated south into Mexico and established their capital at Tenochtitlan (modern-day Mexico City). Spanish conquistador Bernal Diaz del Castillo noted the riches of the market, which dwarfed those of Rome and Constantinople, sophisticated law courts, and, of course, the Great Temple of Tenochtitlan, located at the very center of the city. Del Castillo also noted the ubiquity of gold, which merchants used as currency in the form of dust. This was no backward, primitive world, and even the conquering Spaniards expressed a deep respect for Aztec sophistication. But there was one custom found throughout the Americas that the new arrivals found repulsive: human sacrifice.

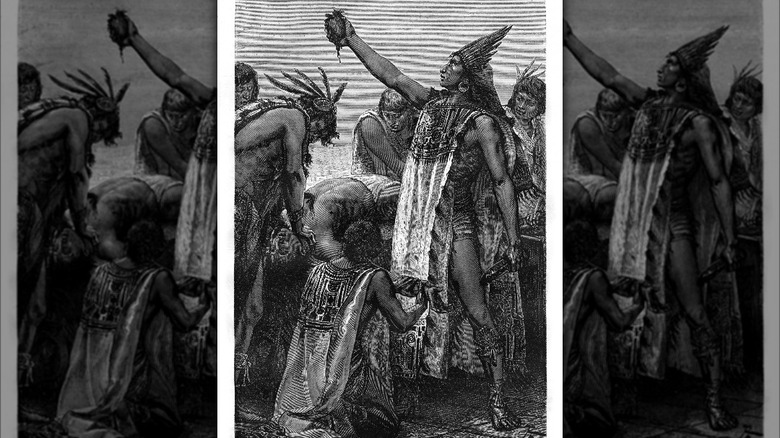

Human sacrifice and blood rituals were facts of life

Although Native Americans are stereotyped as peaceful, pre-Columbian America was, sometimes, a violent place. A number of Native American societies practiced human sacrifice through bloody ritual killings that spanned from the United States to the Andes. According to Smithsonian Magazine, mass graves discovered from Aztalan State Park, Wisconsin to the Southern United States (via Cahokia Mounds Society) attest to the sacrifice of retainers and women in elite burials. The custom extended across the Americas, as evidenced by a mass grave from Peru containing 227 bodies (via BBC). The Encyclopedia of the Great Plains notes that the Pawnee sacrificed captive girls until the 19th century in the Morning Star Ceremony. But no one could match the Aztec Empire's body count.

When Spanish conquistadors toured the Aztec capital, they were unprepared for the grisly scenes that awaited them. According to Bernal Diaz del Castillo, the temples smelled "worse than in a Spanish slaughter-house." The floors and walls of the Great Temple were stained red with blood while the sacrificial platform was covered with burnt heart offerings and coagulated blood. While it might be tempting to see this as a colonialist exaggeration, archaeologists have shown that Spanish descriptions were accurate. Mexican archaeologists uncovered giant skull racks in the ruins of the Great Temple in bone-filled rooms (via Science Magazine). But there was a method to the Aztecs' madness. According to History, human sacrifice ensured the continuation of the sun's rising and of life itself, necessitating a continuous supply of victims. Ultimately, the conquistadors demolished the Great Temple and built Mexico City's cathedral on it.

The Maya invented a number system with zero

In Mexico's Yucatan Peninsula, the Maya civilization blossomed and gave rise to a number of city states. Their cities thrived with pyramid temples that today lie abandoned in the jungles of Southern Mexico and Central America. The Maya influenced Mesoamerica's later civilizations in astronomy, religion, and architecture. They calculated the solar year length down to three decimal places according to the Story of Mathematics, while their monuments required precise measurements and calculations to build correctly. This precision was mostly thanks to their numerical system, which was one of the most sophisticated counting systems of its time.

The Maya used a base-20 (Americans use base-10) number system of dots and lines. A dot represented one or 20 depending on its position, and lines represented five. A third symbol, a shell, represented zero. According to Scientific American, the Maya invented the idea of zero independently at a time when most of the world had no concept of zero. The use of zero made writing Mayan numbers such as 40 easy, unlike Roman numerals, whose complicated notation and lack of zero, according to SOM, made mathematical operations difficult. Thus, instead of writing XXVIII for 28, a Mayan simply wrote one dot for 20 and another group below it, representing eight. Although this achievement never spread worldwide, the independent Mayan use of zero is the biggest piece of evidence for thriving cultures of science and mathematics in the New World.

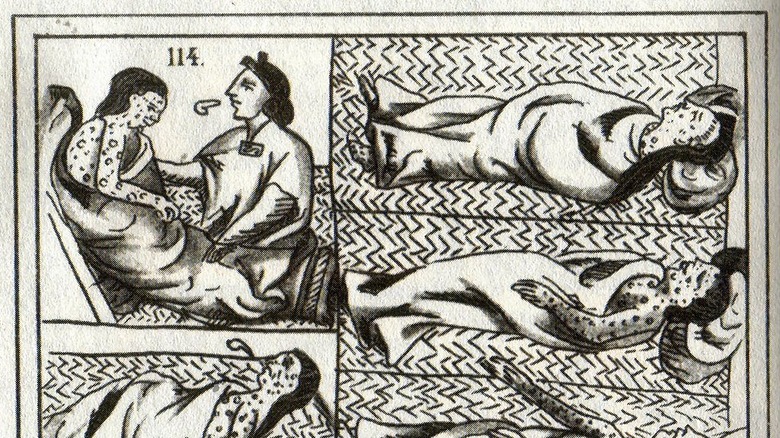

Common diseases were unknown

Eventually, the Americas and their great civilizations were conquered. While scholars credit European colonists' military superiority, PBS notes that most Native Americans fell victim to disease. This is because, in pre-Columbian America, a battery of diseases that were endemic to Europe were completely unknown in the New World, and they came with devastating consequences.

According to professor Henry Dobyns (via professors Nathan Nunn and Nancy Qian), the pre-Columbian inhabitants of the New World did not suffer from (formerly) common diseases such as the flu, diphtheria, smallpox, measles, malaria, pertussis, or chickenpox. The Atlantic notes that the arrival of immune Europeans set off a wave of "virgin soil" epidemics, which first devastated the populations of Mexico and Peru and helped weaken the Inca and Aztec empires. As more Europeans arrived, the outbreaks intensified and spread throughout the Americas.

Since the Native American population had no exposure (and therefore no immunity) to Old World diseases, their population collapsed. Professors Nunn and Qian estimate that around 95% of the indigenous population of the Americas perished from disease by the mid-17th century. According to Smithsonian Magazine, entire populations such as the Taino of modern Hispaniola disappeared as distinct entities, and the survivors intermarried with Spanish arrivals and African slaves. But as the Microbiology Society notes, the native populations of America did return Columbus and his successors the favor. Among the diseases that were introduced to Europe was a venereal disease called the "Great Pox," better known today as syphilis.

There were no horses

The image of mounted Native American warriors riding across the Great Plains on buffalo hunts pervades popular imagination. But the association of Native Americans with horses is a relatively recent one because before 1492, there were no horses in the Americas. LiveScience notes that the last native species of North American horse went extinct around 9,000 B.C. According to History, the Native Americans of the sparsely-populated pre-Columbian Great Plains had to adapt to life without horses. Buffalo meat was plentiful, but buffalo hunting was a dangerous task, especially on foot. Because of their size, hunters crippled buffalo, usually by running them off a cliff, before killing them, and success was fleeting. According to Britannica, early Plains cultures had to supplement hunting with small-scale agriculture to survive.

Columbus re-introduced horses to the Americas in 1493 with a herd of 24 animals. As horses spread, the Native Americans of the Great Plains incorporated the animal into their lives. Mounted warriors could hunt buffalo at less risk to themselves. Thus, according to WNET 13, the horse enabled the settlement of the Great Plains. The diet of the Great Plains Native Americans shifted primarily to buffalo meat, and some phased out agriculture entirely. The Comanche are the best example of this shift, leaving the Rocky Mountains to emerge on the Great Plains as the epitome of the Plains mounted warrior. Their merciless raids against fellow tribes and American settlers made them legendary in the lore of the wild west. None of this would have been possible without their hardy and fast mustangs.

Greenland: two worlds collide

Well before Columbus, another set of Europeans had already found its way to the American continent. According to the BBC, the Vikings were prolific traders and explorers navigating as far as Central Asia using the rivers of Eastern Europe. But they also reached the Americas. Their most famous settlements were on the virgin island of Greenland, which, according to Visit Greenland, is geologically part of the American continent and hosted the first encounters between Native Americans and Europeans.

According to Smithsonian Magazine, Viking expeditions beginning with Erik the Red settled Southern and Western Greenland, creating thriving economies based around animal husbandry and walrus ivory. Norse hunters trekked to the west coast of Greenland to procure the ivory, which made the colonies rich and enabled the creation of beautiful artworks like the Lewis Chessmen. The St. Nicholas Cathedral, built in the 12th century and one of the oldest cathedral buildings in the Americas, is a testament to Greenland's prosperity. But sadly, the good times did not last.

Around 1200, Canadian Geographic notes that the Inuit appeared in Greenland. According to the Christian Science Monitor, these whale- and-seal-hunting nomads lived alongside the Norse (whom they called Kavdlunait) and occasionally traded with them. But they did not intermarry and, according to Inuit tales such as the Legend of Ungortok, even fought each other. In the end, the Inuit won out, and the Norse abandoned their settlements as the climate cooled. When Norwegian missionary Hans Egede looked for his long-lost kin in 1721, all that was left were the crumbling remains of once-beautiful buildings of the New World's first Europeans.

Precision stonework: an Andean specialty

Before Europeans arrived, the great states of the New World were already building monumental stone architecture. The Inca Empire is best known for its magnificent cities like Macchu Picchu, engineered on the difficult terrain of the Andes. But they learned to do that from their predecessors — the Tiwanaku – who engineered a city that has secured its place in the popular imagination for its size and precision.

According to the Washington Post, Puma Punku is a megalithic pyramid that was built with stones quarried from miles away. Some of them weighed up to 160 tons. Yet, the inhabitants of Puma Punku did not have the wheel, so how exactly they hauled such stones to the city is a matter of debate. Archaeologists can only speculate. The dominant theory posits that stones were rolled on wooden logs. But how they cut them so precisely that not even a razor blade could fit between them is a mystery. According to LiveScience, there is no evidence for writing in Tiwanaku, making the question all the more fascinating.

Puma Punku's aura of mystery has also inspired fringe theories claiming that aliens aided in the city's construction. History's Ancient Aliens claims that it would have been difficult for humans, even today, to build a site so precisely and on such a large scale. But perhaps that is a sign that these Andean societies were far more advanced than modern scholarship gives them credit for.

Are the legends true?

Could others have reached America before Columbus? Norse Greenlanders briefly settled Canada in at least one place, L'Anse aux Meadows, around 1000. But according to Irish legend (via Irish Central), the abbot St. Brendan the Navigator equipped a small Irish oxhide boat and sailed west 500 years earlier. According to Chapter 28 of the Voyage of St. Brendan, the crew explored a rich land across the ocean before returning home to Ireland. But was it true, or just symbolic?

Scholars originally deemed St. Brendan's voyage an impossible endeavor, but Tim Severin (via Irish Times) proved otherwise in 1976. Norse legends, according to Indian Country Today, support it. The Saga of the Eyrbyggja (via "The discovery of America by the Northmen, in the tenth century"), tells how Norseman Gudleif Gudlaugson was blown off course and reached an unknown western land whose inhabitants spoke an Irish-sounding language. Danish historian and linguist Carl Rafn concluded that it was "Great Ireland," a land south of the Norse settlements of Vinland (Newfoundland). Rafn, however, also claimed that these settlers left a mark in the Shawnee tribe's oral histories, which allegedly described white-skinned tribes wielding metal tools.

If true, it would mean that Christianity arrived in the New World well before Columbus. As Texas State University professor Kent Reilly notes, anything is possible, but there is no hard evidence outside of legend. In fact, according to the LA Times, most scholars have rejected it as pure fantasy. It is unlikely that the legends were invented, however, so until more evidence is available, it is up to readers to decide on the veracity of these bombshell claims for themselves.