How Power Ballads Changed Rock Forever

Trends in popular music come and go, but there is one dichotomy that has been more or less consistent since the first popular music composers crawled out of the ocean: There are your standard, mid-to-uptempo numbers, and then there are ballads. Each of these served a specific purpose when guests gathered around the piano, visited the local dance hall, or tuned in to old-timey radio. Your standard, non-ballad tunes could prompt a raucous singalong or help you cut a rug (that's old-timey for "dance"), while the slower tunes — often referred to as "torch songs" — were perfect for a nice slow dance with the person you had your eye on, or weeping into your whiskey sour solo.

It took a new genre, though, to find a middle ground. As rock 'n' roll entered its teen years, a curious thing emerged: a melding of musical aesthetics that has carried repercussions to this very day. This aesthetic gave us a new kind of tune — one that employs the pretty melodies and slow tempos of the ballad before building to a rocking, soaring chorus. Let's take a look at how the oft-maligned, ever-popular, lighter-waving trend known as the power ballad came to be, and how that trend became a mainstay of popular music.

Early rock ballads were all ballad, no power

As you may be aware, rock 'n' roll was the product of a giant melting pot of influences. The performers and genres that influenced its development were wildly varied, but among the stronger influences were R&B (then known by the jaw-droppingly inappropriate moniker of "race music"), country, and boogie-woogie. From its inception, rock fielded dreamy ballads to go along with the more, well, rocking numbers, and those were heavily influenced by the popular genre of doowop. During the '50s and '60s, though, the boundary between ballads and rockers was quite clearly marked, and ne'er the twain did meet.

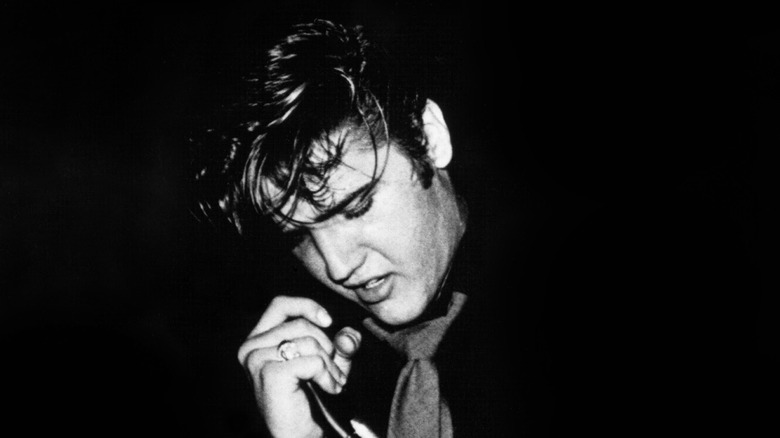

Examples of early rock ballads are as numerous as they are downtempo and dreamy: "Earth Angel" by the Penguins, "Love Me Tender" by Elvis Presley, "Dream" by the Everly Brothers, and "Michelle" by the Beatles, to name only a few. In the late '60s, as the Fab Four were headed to the end of their legendary run, they discovered and eventually signed a band that would play a major role in breaking through that big, fat boundary by injecting one of their ballads with a dose of power.

One of the greatest rock love songs ever planted the seeds of the power ballad

There are few better legs up than being discovered and endorsed by the biggest band in the world, which is the situation that British band Badfinger found themselves in. While their first album on the Beatles' Apple Records label, 1969's "Maybe Tomorrow," didn't perform well, their second did just a bit better, being propelled by the Paul McCartney-penned single "Come and Get It." Their third album, 1970's "No Dice," would yield the Top 10 single "No Matter What" — along with a non-single track that would prove to be as influential as it was innovative.

That track: "Without You," an aching, melancholy ballad that suddenly morphed into a crunching, plodding rocker in its chorus. While the song was never released as a single, it introduced an aesthetic that would suddenly begin to come into vogue within the next couple of years — one that suggested melodic romanticism and dope power chords need not be mutually exclusive. "Without You" would take on a life of its own, becoming one of the most-covered songs of all time. In late 1971, it became a No. 1 hit for singer-songwriter Harry Nilsson, and over 20 years later, Mariah Carey took her version to No. 3.

Early examples of power ballads came from some of the hardest rocking bands

We probably don't need to tell you that in the early '70s, few bands were rocking harder than British outfit Led Zeppelin, who — along with fellow Brits Black Sabbath — were using ultra-heavy drums and even heavier distorted guitars to help pioneer the genre that would come to be known as heavy metal. You have probably heard their signature tune, 1971's "Stairway to Heaven" about 468,000; the chances are actually pretty decent that you're listening to it right now. But if you try just this once to listen to it with a fresh pair of ears, you will realize that — with the exception of the tempo change going into the heavy part near the end — the song checks nearly all of the power ballad boxes, even though that term had yet to be invented.

Even more attuned to this new trend was the 1973 single "Dream On" from Aerosmith which features no such tempo change, and which employs a bridge that builds quite dramatically to its power chord-laden chorus. It's a pretty solid example of the power ballad formula — but at around the same time it was climbing up the charts, another tune that constituted a perfect example of said formula was beginning to get traction on the regional airwaves.

One band's operatic bent crystallized the form

In 1973, Chicago band Styx was still toiling away in relative obscurity, peddling their progressive-inspired rock to audiences directly by way of nonstop touring. Their first three albums, 1972's "Styx," 1973's cleverly-titled "Styx II," and 1974's "The Serpent is Rising," had failed to move many copies, and as lead singer Dennis DeYoung would tell YouTuber Adam Reader in 2021, the band's entreaties to big-market radio stations to play their singles had largely fallen on deaf ears. That is, until 1974 when a curious thing happened: Chicago DJ Jeff Davis of powerhouse station WLS inexplicably started to spin the tune "Lady" from "Styx II," which had been released nearly two years prior.

DeYoung admitted that he hadn't had a solid idea of what he was doing when writing the tune. He was not a trained pianist, but the song's iconic opening piano just sort of came to him. As the writing process continued, his go-big-or-go-home approach dictated that he send the tender ballad hurtling toward a majestic, operatic chorus, complete with march-style drums and huge vocal harmonies.

Davis accurately pegged the song as an overlooked potential smash hit, and his championing of the tune gave it the legs it needed to get traction nationally. In 1976, the song peaked at No. 6 on the Billboard chart. Styx would famously return to the well they helped create with similarly-flavored tunes like "Come Sail Away," "Babe," and "The Best of Times."

A few notable bands hit with power ballads near the end of the classic rock era

For the remainder of the '70s and '80s, a number of bands found that fielding rocking ballads was a reliable way to expand their audiences and achieve chart success without sacrificing their credibility. Interestingly, a good number of these bands also hailed from Chicago, notably ... well, Chicago, which began as a horn-driven outfit with an insanely talented guitarist, Terry Kath. After Kath's death, the band took a pivot toward ballads — starting with "If You Leave Me Now," penned by vocalist Peter Cetera, which was a No. 1 hit in 1976. Follow-ups like "Baby, What a Big Surprise" (1977), "Hard to Say I'm Sorry" (1982), and "Love Me Tomorrow" (also 1982) cemented the band's status as purveyors of rockin' ballads.

Another Chicago outfit, REO Speedwagon, scored a ginormous hit with a quintessential power ballad, "Keep On Lovin' You" in 1980, and San Francisco rockers Journey also found success with the formula in the '70s and '80s with tunes like "Lights" (1978), "Open Arms" (1982), and "Faithfully" (1983). There's a reason, though, that the '80s are remembered as the decade that broke the power ballad wide open — and its cavalcade of emotive rocking began in earnest with one unheralded band, and one singularly unique song.

A relatively obscure band penned the supreme power ballad in 1983

San Francisco's Night Ranger didn't exactly seem like the kind of band that would help change popular music forever. With an assist from burgeoning cable network MTV, they had scored a couple of hard rock hits, like "Don't Tell Me You Love Me," and "(You Can Still) Rock in America," but neither shook the planet. Then, in 1983, drummer and vocalist Kelly Keagy sat down to write a tune after visiting his family and his little sister, Christy, in Oregon. He was feeling melancholy about how fast she was growing up, hanging out and cruising with boys — and in his lyrics, he wistfully hoped for his "Sister Christy" to lay off the "motoring" to focus on "finding Mr. Right."

Speaking with SF Gate in 2005, Keagy recalled that guitarist Jack Blades was a bit puzzled by the tune. "After we started playing it a lot, Jack turned to me and said, 'What exactly are you saying?'" Keagy remembered. "He thought the words were 'Sister Christian,' instead of 'Sister Christy,' so it just stuck."

The tune was released as a single from Night Ranger's 1983 album "Midnight Madness," and when it started picking up steam on the radio, Blades recalled their record label urging them to put together a music video. So it was that in between dates, the band took a break to shoot the video that would send their fortunes, and the power ballad in general, into the stratosphere.

The video for Sister Christian propelled power ballads into the spotlight

As anyone who was around at the time will attest, there was no shortage of absolute weirdness to be found cycling through MTV's rotation in 1983. The video for "Sister Christian," though, struck a serious chord with the station's viewers. Shot at California's San Rafael High School, the video's juxtaposition of religious imagery with cavorting, partying high school kids, interspersed with shots of the band rocking out, was so provocative that it caused more than a little confusion amongst viewers.

"We got all these calls about it," Kelly Keagy told SF Gate. "One woman in Wisconsin said, 'Is this a song about nuns selling dope to school kids?' We said, 'Uh, sure.' The song's about not giving it up before you have to, not letting go of innocence, but people can read into it whatever they want."

The video was played heavily on MTV, and as a result, Night Ranger's popularity went through the roof. Speaking with Classic Rock, guitarist Brad Gillis remembered, "That song really did it for us, man. It took us from middle act to headliner. I'll never forget driving up to a 7,000-seat arena in Wisconsin and seeing 'Night Ranger – Sold Out'. And it was all because of 'Sister Christian.'"

The dominant form of pop-rock became obsessed with the power ballad

The bands then populating the genre that would come to be known as "hair metal" quickly seemed to take notice of what Night Ranger had done. Not long after the success of "Sister Christian," it seemed that every band of that stripe had to include at least one power ballad on each album, and they were quite often hit singles — tunes like Whitesnake's "Is This Love" (reaching No. 2 in 1987), Cinderella's "Don't Know What You Got (Til It's Gone)" (scoring No. 12 in 1988), Bon Jovi's "I'll Be There For You" (achieving No. 1 in 1989), and Warrant's "Heaven" (securing No. 2 in 1989).

But even those that didn't blaze up the charts tended to take on lives of their own. Take Motley Crue's 1985 tune "Home Sweet Home," for example, which only peaked at No. 89 on Billboard's Hot 100, but became one of the band's signature songs. Even old hands like the Scorpions rode the formula to a No. 4 hit with 1990's "Winds of Change," as did power pop veterans Cheap Trick, who scored their first and only No. 1 tune with "The Flame" in 1988.

For the better part of a decade, one simply couldn't listen to rock radio without being serenaded by a rocking ballad. But as the '90s dawned, so did a new trend in music that threatened to put the power ballad on ice.

The power ballad briefly fell out of favor in the '90s

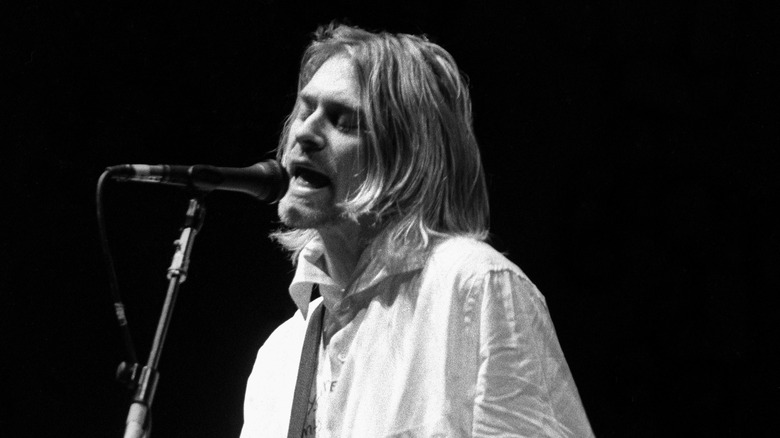

The rock subgenre that briefly pushed the power ballad all the way to the side was grunge, which came roaring out of (mostly) the Pacific Northwest in the early '90s to make instant stars of flannel-clad, riff-heavy bands like Pearl Jam, Soundgarden, and Nirvana. While there was plenty of room for softer elements in the music of these bands — and even a song or two that might technically be considered a ballad such as Nirvana's "Something In the Way" — the subgenre's entire blue-collar, alienated, disaffected aesthetic was so diametrically opposed to the party-hearty image of hair metal bands that the idea of recording a straight-up power ballad must have seemed about as foreign to the above-mentioned bands as dabbling in polkas.

In a 1998 examination of the then-waning grunge phenomenon by The New York Times, it was accurately noted that while they shared an affinity for monster riffs, a key difference between hair metal and grunge lay in the former's emphasis on male swagger and libido, as opposed to the latter's emphasis on male anxiety and insecurity (although it should be pointed out that there were notable female artists in both genres). So, while hair metal bands leveraged the power ballad as an acceptable expression of romantic badassery for fans of the opposite sex, grunge artists simply didn't care, opting for a more introspective (some might even say navel-gazing) form of expression ill-suited to the power ballad form.

Post-Grunge gave the power ballad new life

While grunge music burned brightly — and its most cherished bands, like the aforementioned Pearl Jam and Nirvana, are legends — it proved to have a somewhat limited commercial shelf life. As the fortunes of its purveyors were beginning to dwindle in the mid-to-late '90s, there arose a derivative subgenre to take its place: the not-so-cleverly named, oft-maligned subgenre known as post-grunge.

Generally speaking, this term applied to bands that employed many of the sonic elements of grunge — heavily distorted guitars, loud and heavy drums, middle-of-the-road tempos — and applied a lyrical and vocal aesthetic that was much more, well, self-serious and commercially accessible. Bands such as Bush, Matchbox Twenty, Collective Soul, Creed, and Candlebox made their mark during this era — and with none of the grunge-style hesitation to fully embrace the mainstream, many of these bands played a huge hand in bringing the power ballad roaring back to life.

Interestingly, some of the most well-known of these bands (and songs) carried a Christian bent. For example, Collective Soul's 1994 debut single "Shine" is infused with singer Ed Roland's religious faith; a year and a half after it peaked at No. 11 on the singles chart, the band would score a No. 19 hit with "The World I Know," an unabashed power ballad. Then there is Creed, a band whose religious leanings are well-known, and who scored their only No. 1 hit in 2000 with a mega power ballad, "With Arms Wide Open."

The power ballad lives on today

It may have been classic rock and hair metal bands that brought the power ballad into being, and one can certainly make the case that it was the post-grunge movement that resuscitated the form when it was on life support. But the examples of power ballads that we see today are scattered throughout widely varied genres, proving that a good idea — simply, heartfelt ballads that also rock your face off — can transcend any one style of music.

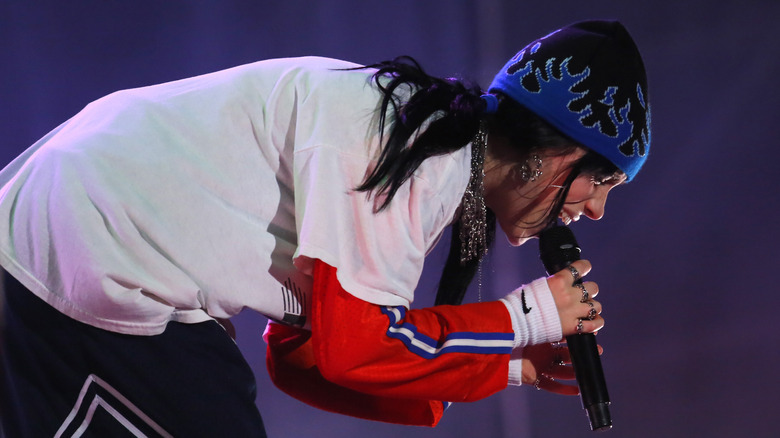

Take, for example, country star Morgan Wallen's "Dying Man," a weeper from his smash No. 1 album "One Thing At a Time," and a power ballad if we have ever heard one. In the world of pop, everyone from Olivia Rodrigo ("Drivers License") to Taylor Swift ("All Too Well") to Billie Eilish ("No Time to Die," from the James Bond film of the same name) has fielded sterling examples of power ballads. Of course, even some hard rockers still indulge — notably Avenged Sevenfold, who have regularly dipped into the power ballad well with tunes like "Seize the Day" and "Set Me Free."

It seems that as long as music fans want a little butt-kicking along with their emoting, there will always be artists to oblige them. Those fans down on the floor at concerts might wave smartphones these days instead of lighters, but the sentiment remains the same: "Rock on, dudes and dudettes. We love ya."