The Turning Point Of The Vietnam War And How It Changed Everything

Looking back today at the Vietnam War, it's easy to see the Tet Offensive as one of the most crucial and important turning points. The attack was launched by the communist North Vietnamese army and the Viet Cong, who were working together against the American and South Vietnamese troops. The offensive got its name from the Tet holiday, which is the day the country celebrates the Lunar New Year and the date on which the North Vietnamese attacked in January 1968.

It's estimated that 85,000 North Vietnamese and Viet Cong troops took part in the attacks, which immediately splashed across the front page of American news outlets, like The New York Times, which quickly informed readers back home that government buildings were on fire, prisoners were being let out of jails, and airfields had been destroyed.

The U.S. and South Vietnamese troops were able to quickly stem the tide and defeat the North Vietnamese and Viet Cong on the battlefield. However, what the North Vietnamese lost in battle, they won in the minds of the American populace. That is, public opinion soon started to shift more in the anti-war direction. Soon thereafter, the U.S. started to reduce the number of troops in the country, leading to the 1973 Paris Peace Accords, although South Vietnam soon fell to the Communists in 1975. Here's what to know about the Tet Offensive, the turning point of the Vietnam War.

The Vietnam War up to Tet

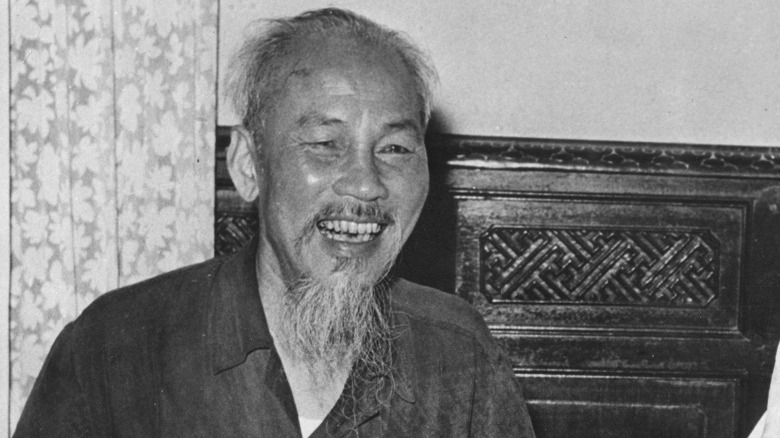

Though it's hard to determine an exact starting point for the Vietnam War, the U.S. first got involved in the country during World War II. At the time, they were working with revolutionaries led by Ho Chi Minh, who would later become the leader of North Vietnam. As an ally, Ho helped rescue downed Allied pilots, but he would soon find himself as the United States' number one enemy. The U.S. abandoned Ho and chose to support the French during the First Indochina War from 1946 to 1954, and then took over for the French following the Geneva Conference.

However, after a decade of political instability and failure on the battlefield from the South Vietnamese army, the U.S. introduced ground troops and started bombing the North Vietnamese in 1965. Still, the Viet Cong and North Vietnamese troops proved to be harder to dislodge than the army had thought, largely due to their guerilla war tactics. By the end of 1967, there were almost half-a-million American troops in the country, but they were still unable to sufficiently turn the tide and evict the North Vietnamese and Viet Cong troops from the south.

This set the stage for the Tet Offensive, in which the North Vietnamese and Viet Cong sought their own victory on the battlefield to remove the foreign American invaders from their country. Soon, the Vietnamese, led by Vo Nguyen Giap, and the U.S., led by William Westmoreland, would meet in a grand fashion.

The arrests that set off Tet

His name is nowhere near as famous in the west as that of his compatriot Ho Chi Minh, but the North Vietnamese communist politician Le Duan was one of the most important men in the entire country during the war. He had been an ally of Ho's since the 1930s and was to assume the leadership of the party following his death in 1969. Yet in 1967, when the planning for the Tet Offensive was beginning, he was competing against numerous other politicians for control of the Vietnam Workers Party (VWP), the name of the Vietnamese Communist Party at the time.

As Lien-Hang T. Nguyen explains in "Hanoi's War," on one side stood Ho and the leader of the Vietnamese army, Vo Nguyen Giap. On the other were Le Duan and his allies. Le Duan's faction was known as the "south-first" because they advocated for the struggle in South Vietnam among the guerillas. In early 1967, Le Duan started to push for a renewed offensive in the south because he felt the time was ripe for another uprising to finally shake off the American yoke for good.

In order to push his plans through, Le Duan helped oversee what is known as the "Revisionist Anti-Party Affair." These were a series of arrests of VWP members, professors, journalists, officers in the army, and others. These arrests allowed Le Duan to push through the resolutions necessary to start the Tet Offensive.

The planning begins

In July of 1967, following the death of high-ranking Commander General Nguyen Chi Thanh in North Vietnam, Le Duan started to make plans for the upcoming Tet Offensive. Le Duan had already decided on implementing his "General Offensive and General Uprising" strategy to get the Americans out of Vietnam. With Thanh's death, he was presented with the perfect co-conspirator for his plans (per "Hanoi's War"). His ally would be Senior General Van Tien Dung, who, like Le Duan, had been a longtime member of the Vietnamese communist struggle.

Upon Thanh's death, Dung and Le Duan had a secret meeting — without notifying the leader of the army Vo Nguyen Giap — where they discussed plans for the Tet Offensive. Yet, when they unveiled their plans to the Vietnam Workers Party (VWP) politburo, they faced stiff backlash from Ho Chi Minh, the founder of the North Vietnam Revolution and one of the most popular people in the country.

However, by this point, Ho was no longer the political force he was in his younger days. He was largely out of favor in the VWP by this point, relegated to being mainly a symbolic presence above anything else. Le Duan was easily able to deflect Ho's criticism, setting the stage for him and Dung to begin their new offensive in early 1968. In late 1967, the first skirmishes of what would become the Tet Offensive kicked off, with the full-scale attack coming just months later.

The Tet Offensive kicks off in January 1968

After months of machinations and planning, the Tet Offensive officially kicked off on January 31, 1968. Even though a tentative truce was in place due to the Lunar New Year celebration, the North Vietnamese and Viet Cong attacked, catching many troops completely by surprise. However, the U.S. Army was aware that a communist offensive was potentially in the works due to limited skirmishes throughout the country in the months prior.

Still, on January 31, from Camau and Vinh Long in the south, all the way through Quangtri and Khe Sanh in the north, the North Vietnamese troops and Viet Cong guerillas launched relentless barrages against many different American and South Vietnamese locations. In Saigon alone, there was a 4,000-man force that attacked numerous installations, including the U.S. embassy, according to "Vietnam, a History." Using munitions trafficked in secretly through shipments of rice, they stormed the embassy after knocking a hole in the wall, occupying the building for several hours until they could be knocked out.

The communists did make one mistake, which was to launch the attack early in areas along the Central Highlands. This was due to a miscommunication between troops, who were inexplicably using different calendars. Yet, when the real attack kicked off, it still caught many troops by surprise, and the sheer size and strength were shocking to everyone.

The radio station siege

One of the biggest targets for the Viet Cong during the Tet Offensive was the radio station in the capital of Saigon. Author Stanley Karnow shared the story of one of the men who attacked the radio station, Dang Xuan Teo, in "Vietnam: A History." Teo recalled that they began planning late the year prior when he was personally selected by the upper brass. The initial plan was to hold the building until reinforcements could arrive, but they never showed up.

They got into the station by blasting through the gate with dynamite before quickly taking out all of the guards on duty. Short on arms, the Viet Cong commandos were only able to hold onto the building for a few hours before they knew they were to be overwhelmed. They wanted to take over the station and start broadcasting communist propaganda recordings throughout Saigon. However, unbeknownst to the infiltrators, the station was offline from the beginning, making the entire attack futile and useless.

Teo was able to escape from the station to try and get some help, but the remaining commandos blew up the building before he could make it back, sacrificing themselves for their cause. Their bodies were looted and trampled by South Vietnamese troops looking for valuables, and only Teo survived to relay the tragic story years later.

The Tet Offensive had multiple waves

While many people think the Tet Offensive was a short-lived battle that only lasted for a couple of months in early 1968, it was actually carried out in three separate waves that took up most of the year. The first attacks launched on January 30 and 31, 1968, lasted for a month until the end of February. For the most part, the attacks were a military failure, and they did not incite the uprisings among the civilian population like Le Duan had hoped for.

Still, the second wave was launched just over two months after the first ended, on May 4, 1968. This time, the Viet Cong and North Vietnamese targeted over 100 bases and installations (via "Hanoi's War"). However, the results were similar to the first wave, and the communists suffered many casualties. All of this was happening over the backdrop of peace negotiations, which first began just over a week after the second wave was launched on May 13.

The second wave ended on August 17, and on the same day the third wave started, but it ended just over a month later and accomplished little. Le Duan and the communists were hoping to use favorable conditions on the battlefield to influence peace negotiations, as they had during the previous war. But the success on the front lines never came, hampering the North's representative Le Duc Tho at the peace talks in Paris.

The fighting at Hue and Khe Sanh

While the Tet Offensive took part throughout most of South Vietnam, two of the biggest battles took place at Hue and Khe Sanh in the north. At Hue, the communists quickly took over the citadel in the city and were able to hold it for nearly a month. All of Hue was subject to their wrath. They executed thousands of residents and buried them in the jungle and rivers, though the Vietnamese government denied this occurred.

In Hue, the Viet Cong also targeted American officials and Catholic clergy members, murdering them during battle. U.S. soldiers finally re-took the city and declared victory in early March, but it was at a serious cost. Combined, the U.S. Army and Marines lost 221 soldiers and had 1,364 casualties. That paled in comparison to the as many as 5,000 communists they killed (via "The Tet Offensive").

The fighting at Khe Sanh was just as savage and contributed to even more deaths. President Lyndon B. Johnson kept track of the battle from Washington through a miniature model. Army General William Westmoreland mistakenly believed that the Marine base there was the target of the Tet operations, and he poured massive amounts of material into defending it. However, it was mainly a feint by the communists to draw the Americans from other areas in the south, which it successfully did. At Khe Sanh, as many as 15,000 communists died compared with just 205 Americans, per "The Army and Vietnam."

The Tet Offensive was a complete military failure

Today, we look back at the Tet Offensive as one of the decisive turning points in the war, but for the communists, it was a complete military failure. The purpose of the Tet Offensive was to launch a surprise attack that could show the weakness of the American and South Vietnamese position and push the huge civilian population to rally against the communists. However, that widely failed and the communists faced massive casualties without being able to hold any sustained resistance.

The official U.S. estimates for the communist casualties are 37,000 dead and 6,000 taken prisoner within just a month, and the fighting still continued throughout the year. The Viet Cong as a fighting force was completely decimated and their entire infrastructure was severely weakened. With the exception of Hue and Saigon, the communists struggled to hold out on any territory for even a limited amount of time.

Even though the offensive was faltering, Le Duan in the north continued to call for successive second and third waves, but they were hardly effective in turning the tide. The southern resistance was obliterated until the early 1970s, weakening their position as the U.S. and South Vietnamese quickly recovered.

The execution of Nguyen Van Lem

Of all the haunting and chilling images produced during Vietnam, the execution of Nguyen Van Lem during the Tet Offensive has long stood out as one the most gruesome and stark showcases of the disturbing reality of war. The execution was caught on video and carried out in Saigon, South Vietnam on February 1, 1968, just after the offensive had started. The shooter was the chief of police and a brigadier general in the army, Nguyen Ngoc Loan.

The reason for Lem's detainment itself is disconcerting, as he was reportedly responsible for killing a South Vietnamese colonel along with his entire family — including several children. Loan was familiar with the colonel, which may have played a role in him carrying out the summary execution. Still, the image of a handcuffed man being executed in the middle of the street — a likely war crime — shocked and dismayed U.S. audiences who watched it on TV and saw the picture in the papers.

The video is extraordinarily gruesome, and also led to Loan becoming somewhat of a pariah in the press and halls of the U.S. Congress. Loan died in 1998 of cancer, and Ernie Adams — the videographer who captured the incident — expressed sympathy for Loan's actions and suggested the video should be viewed in the context of what Lem had allegedly done.

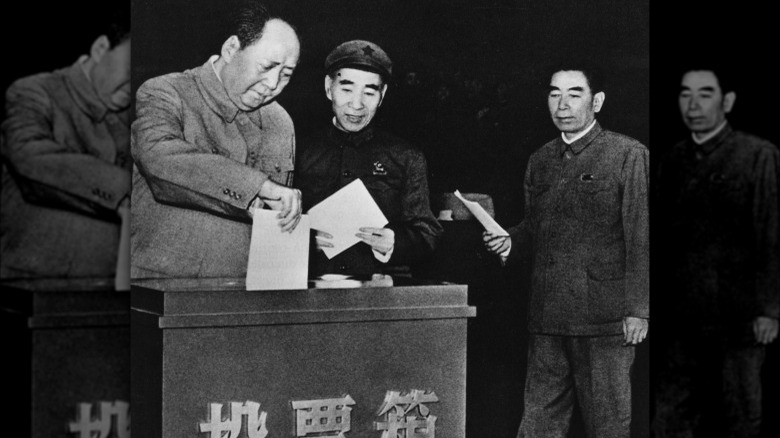

North Vietnam's allies did not approve of the Tet Offensive

During the Vietnam War, the major allies of the Democratic Republic of Vietnam (DRV) were the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR) and the People's Republic of China (PRC). And while both of them provided assistance to the DRV during the war, the PRC was very unhappy with Le Duan's decision to go through with the Tet Offensive in early 1968. As explained in "Hanoi's War," the PRC leaders in Beijing thought the entire Tet Offensive and Le Duan's switch to begin his "General Uprising, General Offensive" strategy was done too early and would not be effective.

They also worried that the entire idea meant the DRV was falling more into the Soviet orbit and further away from them. At the time, the Soviets and the Chinese were involved in a bitter struggle against each other, despite being the two largest communist countries at the time. In addition, the start of peace negotiations between the DRV and the U.S. also muddied the Sino-Viet relationship, which they also saw as a pro-Soviet move. As the offensive continued throughout 1968, the PRC became more vocal in their opposition, but Le Duan defied them and continued on with the futile third wave.

President Johnson decides not to run for reelection

One of the biggest consequences of the war was the subsequent decision by President Lyndon Johnson to forgo reelection at the end of the year. Johnson had taken over for the previous president, John F. Kennedy, in late 1963 following his assassination. He won reelection in 1964, but by the first weeks of Tet in 1968, his public support was crumbling. Less than ⅓ of the country still backed him, and even Congress was vocal about their misgivings of Johnson and the Tet attacks.

The worsening economy did not help, and word leaked about General William Westmoreland's troop request for an additional 206,000 men, further damaging the public's view of Johnson's prosecution of the war, per "The Tet Offensive." His approval rating on Vietnam dropped further, sputtering with barely ¼ of the public on his side. Following a poor showing at the New Hampshire primary, where antiwar candidate Senator Eugene McCarthy nearly beat him, as well as the entrance of Robert Kennedy to the race, Johnson made the difficult decision to not seek reelection at the end of the year.

On March 31, 1968, on the two-month anniversary of the attacks, Johnson made one of the most fateful speeches in the history of the presidency. He announced not only that he was largely stopping the bombing campaign against North Vietnam, but he also called on them to begin peace deliberations. Finally, he announced his refusal to seek reelection, shocking the nation.

The Tet Offensive changed American public opinion

Initially, when the Tet Offensive kicked off in early 1968, Americans became patriotic and were supportive of the troops facing the communist attacks. However, that support quickly turned back to disillusion as daily broadcasts and reports showed bloody and explosive battles tearing apart the country. The army's insistence that the Tet Offensive actually meant that the communists were faltering and on their last legs belied what the public was readily able to watch and read every day.

For many, the turning point came when trusted news anchor Walter Cronkite made a dire prognosis of the war following the outbreak of Tet. After visiting with Marines in Hue, Cronkite told the nation that the U.S. and South Vietnamese troops were not on a path to victory and that the war was at a virtual impasse. It was a change from his earlier broadcasts and a clear sign of the shift in public opinion.

Soon thereafter, President Lyndon Johnson announced a partial halt to the bombing program, opened peace negotiations, and announced he would not be seeking reelection. The war was far from over, with the U.S. not vacating the country until just over five years later, and South Vietnam falling to the communists in 1975. Yet Tet provided a significant impetus for wind-down in the U.S.' involvement, which played a large role in finally ending the war.