The Twisted History Of Pol Pot

The 20th century was a period of extreme ideologies and terrible violence. Millions died in the camps of Nazi-occupied Europe, the gulags of Soviet Russia, and across China during Mao Zedong's "Great Leap Forward." But in terms of self-destructive insanity, it could be argued that none of these events quite matched Pol Pot's Cambodia.

Pol Pot and the Khmer Rouge regime overthrew General Lon Nol's military government on April 17, 1975, and for the next four years, Pot attempted to reshape the nation according to his extreme communist ideals, which were a hodgepodge of Marxism, Leninism, Stalinism, and Maoism.

The Cambodian genocide stood out because it was an extremely aggressive death campaign against its general population, rather than just political enemies and those considered to be "others." It differed, too, from the absurdity of Mao's "Great Leap Forward," the primary effect of which — famine – killed millions from 1958 to 1962. The Khmer Rouge's actions were genocidal to its own population, and when the Vietnamese army ousted the regime in 1979, what they discovered necessitated a grim new term — autogenocide.

The following article includes descriptions of torture and genocide.

Pol Pot was secretive and enigmatic

Pol Pot was born Saloth Sar on May 19, 1925, but few knew this during his reign, for the dictator was committed to obscuring his identity. As recounted in Philip Short's "Pol Pot: The History of a Nightmare," Pot told a comrade, "If you preserve secrecy, half the battle is already won."

As an insurgent in the 1960s and 1970s, Sar operated under numerous aliases such as Pouk, "87," Grand-Uncle, and First Brother. This so confused domestic and foreign observers that in 1971, just four years before the Khmer Rouge captured power, Saloth Sar was simply counted as one of many notable patriotic intellectuals.

Sar presented his infamous identity to the Cambodian people in 1976, but as David Chandler detailed in "Pol Pot Brother Number One: A Political Biography Of Pol Pot," the dictator told them nothing beyond his moniker, "Pol Pot." "We still didn't know who Pol Pot was," said survivor Luong Ung, "We didn't know what kind of a man he was, we didn't know what he looked like." Pot's identity was hidden even from his brothers, who only discovered the truth when they saw Pot's picture in mid-1978.

Pot's character became clear during his exile in the Cambodian wilderness, but confusion about his age persisted until his death. Journalists and historians once referred to French colonial records, which state that Pot was born on May 25, 1928, but Pot and his siblings insisted that he was three years older, causing Chandler and other historians to revise the historical record.

His communist posturing belied a privileged upbringing

Pol Pot presented himself as a modest communist hero, but the reality was far more bourgeois. He was born into a farming family, although his father, Pen Saloth, was wealthy enough — thanks to his sizable and profitable rice land holdings — to afford a home with roof tiles, rather than the thatched, perishable construction known to most Cambodians at the time. The family also had connections to the Royal Palace in Phnom Penh, especially Pot's cousin Meak, who had a son with Prince Sisowath Monivong and remained a palace fixture until the 1970s.

Years later, when Saloth Sar had become Pol Pot, this milieu of privilege was buried under communist mythologizing at home and abroad, according to "Pol Pot Brother Number One: A Political Biography Of Pol Pot." North Korea was the first country to broadcast a Pol Pot narrative to the outside world, and it was replete with falsehoods and disingenuous omissions. It presented the Cambodian leader as a simple farm worker who developed revolutionary zeal as a college student, neglecting to mention that the farm was family-owned and the education was received not in provincial Cambodia, but in the heart of imperial Paris.

He was amiable and well liked

Pol Pot was a teacher in Phnom Penh during the 1950s, and students remembered him as an effective communicator who was honest and easygoing, with one acquaintance going so far as to say, "I saw immediately that I could become his friend for life" (via "Pol Pot Brother Number One: A Political Biography Of Pol Pot"). Pot maintained this charm throughout his dictatorship, and it registered even among party defectors, who never blamed him for their disillusionment.

You can get a sense of Pot's manner from photos of his broad, toothy smile, such as those where Pot, uniformed in an idealized agrarian scene, embodies the perfect Khmer citizen (via Associated Press). Such posturing was propaganda, but historians have wrestled with questions about Pot's wider affability for decades. Was there genuine warmth to the dictator's personality, or did he use kindliness to disarm and deceive? Such questions only beget further questions about those four terrible years. Namely, did Pot really believe in his ideology, or was he just a cynical egotist indifferent to human suffering?

In his attempt to understand this aspect of Pot, David Chandler wrote: "... it has been impossible for me to penetrate what may be a facade, a series of masks, or a chosen repertoire of skills," and stated that even after Pot gave a rare, two-hour interview to journalist Nate Thayer, the dictator remained an inscrutable figure.

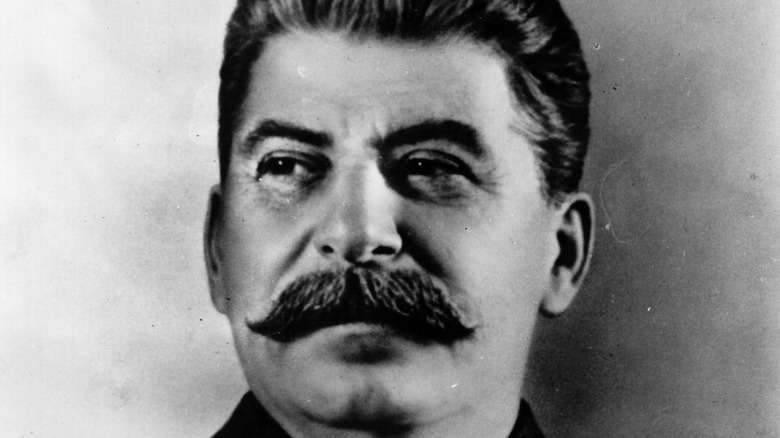

He was inspired by Joseph Stalin

Pol Pot found inspiration in Joseph Stalin, one of the 20th century's most brutal tyrants. The young Saloth Sar was exposed to his influence in Paris, where he studied during the late 1940s and early 1950s, and it motivated him to join Marxist circles and perhaps even the French Communist Party (PCF).

Pot's Marxist fraternizing introduced him to Ieng Sary and In Sokhan, fellow Cambodians and committed Stalinists who decorated their walls with the dictator's image, according to "Pol Pot: The History of a Nightmare." They consulted numerous radical texts together, such as "The Communist Manifesto" and Vladimir Lenin's "ABC of Communism," but it was Stalin's "The History of Communism" that proved especially formative in developing Pot's ideology.

It didn't seem to matter that Stalin had written the book during the Great Terror, a sweeping political purge that killed an estimated 750,000 people. In fact, given what Pot and his men would turn into, they likely viewed the Great Terror as an appropriate response to those Stalin termed: "[the] doubters, opportunists, capitulationists, and traitors within the leading headquarters of the working class". Saloth Sar followed the Soviet dictator in adopting a moniker ("Stalin," derived from the Russian word for steel 'stal,' was born Ioseb Dzhugashvili). Sar's choice of "Pol Pot" was much less macho and aggrandizing, for the name was typical of the Cambodian agrarian class, according to "Pol Pot Brother Number One: A Political Biography Of Pol Pot."

The Khmer Rouge announced Year Zero

When Pol Pot returned to Cambodia in 1953 from his education in Paris, he had a mission to revolutionize his country into a Marxist-Leninist utopia, and he was prepared to take his time in doing so. At the same time as he organized with the Khmer People's Revolutionary Party (KPRP), Pot spent several years working as a teacher. However, this balance became untenable in 1963, when a government crackdown forced Pot and his comrades into the jungles of northern Cambodia.

It was here that the Khmer Rouge emerged as a serious military force. A 1968 insurgency bolstered and expanded their control of northern Cambodia, but it wasn't until General Lon Nol's coup d'etat in March 1970 that they made rapid territorial gains. Fighting between the Khmer Rouge and Lon Nol's forces lasted over five years, and it was assisted by overspill from the Vietnam War, including a U.S. bombing campaign that dwarfed those conducted over Japan during World War II.

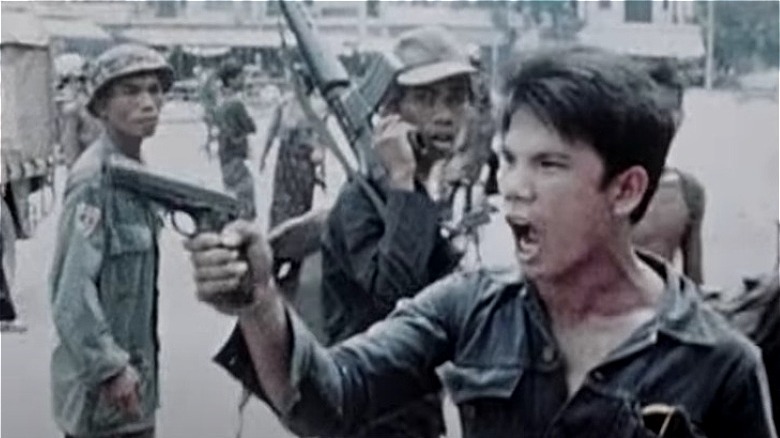

In January 1975, as the last vestiges of American power left southeast Asia, the Khmer Rouge began its invasion of Phnom Penh. Three months later, on April 17, after relentless artillery strikes, the city and country fell. The Khmer Rouge could now implement their notion of "Year Zero," which was to strip Cambodia of its history, culture, and all modern infrastructure. As John Pilger explained in 1979, money, medicine, education, religion, and even friendship and family were all banned. In Pol Pot's Cambodia, one could do nothing but work themselves to death.

Cambodian towns and cities were forcibly evacuated

With Phnom Penh secure, the Khmer Rouge wasted no time in removing the populace. French writer Francois Ponchaud was caught up in the exodus, and he documented his experiences in the haunting book "Cambodia: Year Zero." He observed soldiers going door-to-door and instructing residents to flee because of an incoming strike by the U.S. Air Force. "Go ten or twelve miles away," the uniformed men would say, "Don't take much with you, don't bother to lock up, we'll take care of everything until you get back."

Of course, there was no U.S. strike, and there was no getting back. The Khmer Rouge managed to evacuate the city's two million inhabitants in just 72 hours, sending throngs of people toward their new rural homes, which were spartan huts assembled across Cambodia's central plain.

Life in the fields was unspeakably harsh, and it came with many new rules – some strange, others torturous. For instance, workers were not allowed to use the word "sleep." Instead, they could only "rest". Presumably, to "sleep" was somehow lazy, indulgent, and anti-revolutionary. Far worse than tyrannical semantics, however, was the rationing of marriage: Husbands and wives could see each other only once a month, which was a concession made out of reproductive necessity.

The ensuing genocide killed 1.5 to 2 million people

Violence was arbitrary during the mass exodus of April 17, 1975. In "Cambodia: Year Zero," Francois Ponchaud recounted soldiers waving assault rifles and stealing whatever they could find, such as watches, motorbikes, and, strangely, a ballpoint pen, for which Ponchaud was almost killed. Such opportunism was just the start of the inhumanity that defined Cambodian life for the next four years.

Public officials were the first to be murdered. Then, on May 20, just over a month later, the Khmer Rouge shifted its attention to the masses. Anyone suspected of non-conformity faced death, and non-conformity could include speaking another language and even owning a pair of glasses, for these traits were "intellectual," according to the Khmer Rouge's warped ideology. Other targets included Buddhist monks, Cham Muslims, and those of Thai, Chinese, and Vietnamese origin. However, while the Khmer Rouge directed special enmity toward these groups, the Cambodian genocide represented societal autogenocide rather than a focused murder campaign: If you fitted the Khmer Rouge's vague notions of dissent – you were dead.

Our World in Data shows that in 1975 and 1976, Cambodia's life expectancy plummeted from 39.8 to just 12 years old. This climbed to 28.9 years in 1977, but the Khmer Rouge continued to murder their citizens in what journalist Dith Pran called the "killing fields," according to Sydney Schanberg's book "The Death and Life of Dith Pran." When Vietnamese troops toppled the regime in January 1979, up to two million people were dead, including much of the country's professional and technical class.

Pot oversaw the notorious S-21 detention center

Much of the Khmer Rouge's worst violence occurred in Security Prison 21 (S-21), a former secondary school that was repurposed as a torture chamber. Of the 20,000 people detained at S-21, only seven survived.

One victim by the name of Mr. Peg, who spoke with filmmaker John Pilger, recounted how he was struck over the head some 50 times with a piece of wood before having his hand clamped in a vice, his fingernails removed, and doused with alcohol. Such sadism was unremarkable in an institution where electrocution and disembowelment were commonplace.

The savagery of S-21 was distinct from the tyranny of China and Vietnam, because while those movements broadly considered violence to be a "necessary evil," the Khmer Rouge positively reveled in it. Ultimately, Pol Pot took the economic mismanagement of Mao's "Great Leap Forward" and combined it with the bestial savagery of the Spanish Inquisition. If one needs any further proof of the Khmer Rouge's obsession with violence, it can be found in the regime's national anthem, which exults: "bright red blood covers the towns and plains of Kampuchea" and "blood changes into unrelenting hatred and resolute struggle [which] frees us from slavery."

He was an ally of China and North Korea

As Cambodia continued its slide into the abyss, Pol Pot and his entourage embarked on a diplomatic tour of China and North Korea, two of the most oppressive regimes of the 20th and 21st centuries. Modern technology was banned for ordinary Cambodians, but the Khmer ambassadors landed at Beijing airport on September 28, 1977, and basked in a crowd of some 100,000 spectators.

Pot's idol Mao Zedong had died a year prior to the trip, but the Cambodian leader had a warm relationship with China's new premier, Hua Guofeng, who praised Pot's leadership, saying, "[It was] relying on the masses, upholding independence, and persisting in armed struggle." The nonsensical back-patting continued several days later in North Korea, where President Kim Il Sung decorated Pot and celebrated him on state television as a noble farmhand committed to patriotic struggle.

Incidentally, the photos of Pot's meeting with Hua Guofeng were the first images of Pot to be broadcast to the world, allowing foreign observers to identify him as Saloth Sar.

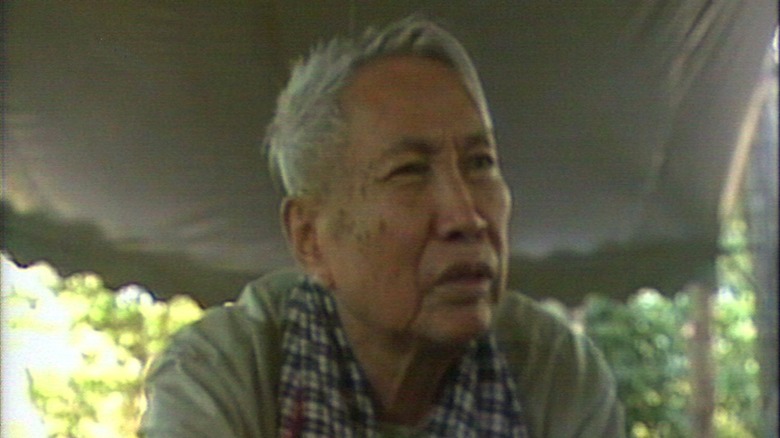

He expressed no remorse

In an interview with Radio Free Asia, American journalist Nate Thayer described Pol Pot as "strikingly charming," when he entered his jungle compound near the Thai border. It was late 1997, and the former dictator was under house arrest and only months from death, but he hadn't lost his old amiable manner. However, such warmth was mooted by Pot's psychotic lack of guilt for killing one-quarter of the Cambodian people. Asked whether he was a mass murderer, the revolutionary said that while he had made mistakes, his conscience remained clear because he believed the Khmer Rouge had generally been a force for good.

Thayer used numerous tactics to elicit a response that aligned with any right-thinking person's idea of the genocide, but Pot was elusive and disingenuous. The dictator claimed ignorance of S-21 — the notorious death prison — and when he was asked to rationalize the emptying of Cambodia's villages, towns, and cities, Pot insisted that the Khmer Rouge were acting out of self-preservation against their enemies, namely the Vietnamese. At no point did the delusional aged man realize that he had done more to destroy Cambodia than anyone else.

Pol Pot was never brought to justice

Pol Pot evaded the Vietnamese army in 1979 and fled to the Cambodian jungles near the Thai border, where he and his Khmer Rouge comrades maintained a guerilla struggle for some 20 years, until the dictator's death in 1998. "Pol Pot died just as the world finally seemed to be serious about bringing him to justice," read the dictator's obituary in The New York Times.

The first step to justice occurred months prior in 1997, when the Khmer Rouge denounced their aging leader and launched a trial, eventually sentencing Pot to life imprisonment. With his authority and movement finally over, Pot's health deteriorated and, on April 15, 1998, he reportedly died from heart failure. Nate Thayer claimed (via the BBC) that Pot had taken a cocktail of drugs in fear of apprehension by American forces, but the US State Department denied any intentions of capturing Pot.

The cause of Pot's death will likely never be verified, but the funeral was unequivocally inglorious. Preserved in formaldehyde and processed by Thai forensics, Pot's coffin was hoisted onto a bed of car tires and detritus, where his remains burned in a plume of thick, foul smoke.