History's Most Famous Traitors

The only thing worse than an enemy is an enemy who used to be your friend. According to Italian poet and all-around genius Dante Alighieri, the ninth and deepest circle of hell is reserved for traitors. That said, every traitor has a backstory, and a surprising number of traitors have abject defenders.

Throughout history, men and women have sold out their friends, families, and homelands, for gold or glory. Others have committed betrayals based on strongly held religious and political convictions. During the early 20th century in particular, WWII and the Cold War created powerful ideological divisions that pitted brother against brother, resulting in a whole generation of turncoats and defectors.

Treachery is hard to forgive, and the worst of the worst are still spoken about in tones of disgust today. On occasion, well-timed acts of subterfuge have changed the fate of entire nations, as in the case of India's Mir Jafar and Ireland's Diarmait Mac Murchada. Other notorious traitors — including Judas, Vidkun Quisling, and Benedict Arnold — have actually changed our language, spawning new words for backstabbing behavior.

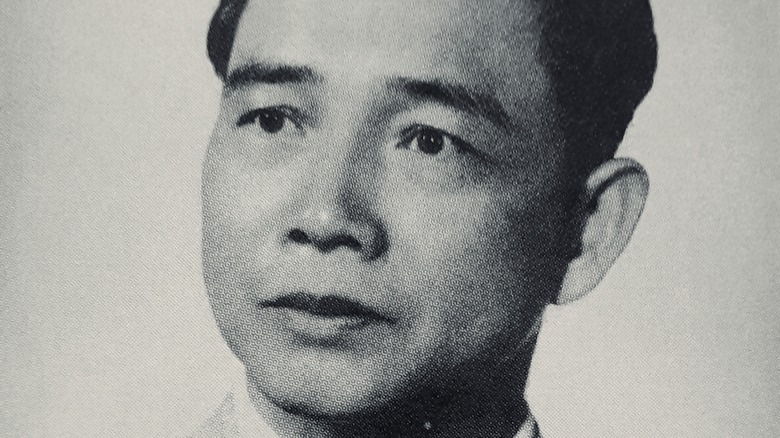

Wang Jingwei

A divisive character with an impressive career history, Wang Jingwei is China's Benedict Arnold. As a young man, Wang was heavily involved in Sun Yat-sen's revolutionary movement that aimed to modernize China and found a republic. Wang even attempted to assassinate one of the last Qing royals, Prince Chun. During the pre-war years, he went on to become a prominent politician.

Then, in 1937, the Second Sino-Japanese War began, and the Japanese seized Beijing, Shanghai, and Nanjing. To the horror of many, Wang cooperated with the invaders. The Japanese created a new puppet government in Nanjing, and in 1940, Wang was made the head of that government. Wang argued that he was only trying to protect the Chinese people; appeasement seemed like a sensible option against a much stronger Japan.

For most Chinese people, Wang's actions would prove to be unforgivable in light of Japanese atrocities in the country. The so-called "Rape of Nanjing," for example, conducted by the Japanese in 1937, is still one of the worst disasters to ever befall China. Thousands of men were killed, and thousands of women were systematically raped in a six-week orgy of brutal sadism. The controversial politician was never held accountable for his treachery and died before the end of the war, in 1944.

Vidkun Quisling

Vidkun Quisling (left) — the man who gave us the English insult "Quisling" –was a Norwegian military officer and politician who sold Norway out to the Nazis. The deeply antisemitic Quisling founded his own version of the National Socialist Party in Norway before the Nazis even arrived. However, it turned out to be wildly unpopular. According to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, his party only received 2.2% of the vote in 1933, falling to 1.8% in 1936.

Unable to see any parliamentary success, Quisling actually asked the Nazis to invade during a trip to Germany in 1939. A year later in 1940, he got his wish — the Nazis arrived, and Quisling took the opportunity to declare himself the head of Norway's new government. The outrageous takeover was greeted with bombs and fires in Oslo, laid by the disgruntled populace.

In the weeks that followed, the Nazis organized a new government, but they awarded Quisling the title of "Minister President" and allowed him a large amount of power. Under the new regime, Quisling embarked on a grotesque antisemitic crusade that left deep scars on the country. He immediately banned Jewish people from entering Norway, had Norwegian Jews imprisoned en masse, and sent many men and women to Auschwitz. After the war, Quisling was shot for his crimes in 1945 following a brief trial.

La Malinche

La Malinche (otherwise known as Malinal or Doña Marina) was once the lover of Hernán Cortés, and she has been seen as a traitor in Mexico since Mexican Independence. That said, not everybody is so keen to condemn Malinche today, as she probably did not have much choice in the relationship.

The daughter of a local chief, the multilingual Malinche was sold into slavery after the death of her father, and eventually given to the Spanish as a gift, along with a handful of other women. Being both highly educated and good at languages, she ended up working as an interpreter for the conquistadors and became an invaluable guide. Although Cortés does not talk about her much in his letters, we know that she both gave him a child and saved his neck on at least one occasion after uncovering a plot against him. The information Malinche gave the Spanish ultimately helped them to seize the Aztec capital of Tenochtitlan and conquer the empire. As a result, the word "malinchista" has come to mean someone who betrays their culture in Mexican Spanish.

Nonetheless, Malinche has some defenders. According to NPR, in the 1960s and '70s, she was rehabilitated by some within the feminist movement who saw her as a woman caught between warring cultures. Having been kidnapped and passed around like an object, it is easy to recast Malinche as a victim. Today, the complex character of La Malinche is the subject of a huge amount of Mexican artwork that explores her character and confused legacy.

Judas Iscariot

Judas Iscariot is perhaps the most famous traitor of all time, having betrayed the son of God himself for 30 measly pieces of silver. According to the Bible, Judas made a pact with the Jewish establishment to turn Jesus in, in exchange for cash. While loitering in the Garden of Gethsemane in Jerusalem, Judas kissed Jesus to identify him to the Jewish high priests and their armed gang. Following Jesus' crucifixion, Matthew 27 tells us Judas was horrified by what he had done: "... And throwing down the pieces of silver into the temple, he departed, and he went and hanged himself."

Whatever your religious convictions, Judas is a fascinating character whose psychology has been explored again and again in film and other media. The biblical version of Judas is perhaps the hardest to understand, as the Bible does not explain his motivations in great detail. The Gospels do hint that Judas was greedy, calling him a thief in the Gospel of John 12. Pop culture depictions of Judas, on the other hand, have often attempted to flesh out his character and explain his motivations. The Judas who appears in the hit musical "Jesus Christ Superstar," for example, is genuinely concerned that Jesus is a dangerous radical, singing "I remember when this whole thing began/No talk of God then, we called you a man ... And they'll hurt you if they think you've lied" (via STLyrics).

Finally, the Gnostic "Gospel of Judas" presents us with an alternative Judas, who is innocent. In the mysterious text, Jesus actually asks Judas to betray him so that he can save mankind.

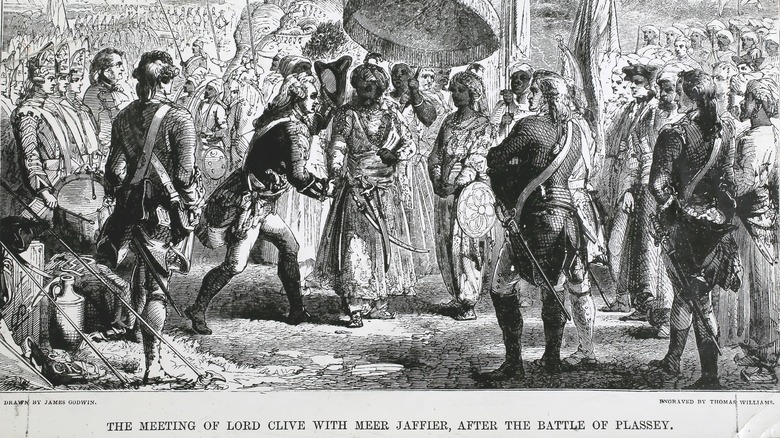

Mir Jafar

During the British Empire's seemingly unstoppable expansion, divide-and-rule tactics were used again and again to seize control of large regions with few men. During the 18th century, the Indian subcontinent, beset by factionalism as the ruling Mughal Empire decayed, was particularly vulnerable to this gambit. All the British had to do was find someone with absolutely no integrity and offer them some benefit. In India, that man was Mir Jafar, an unpleasant character who sold out his home state of Bengal for the promise of power.

Jafar was supposed to bring his troops to battle in support of the Nawab of Bengal, Siraj ud-Daulah. Siraj was rightly nervous about the British East India Company's creeping presence in India, so he tried to remove them from the region and ended up in a pitched battle. Before the two sides met at the West Bengal village of Plassey, however, British official Robert Clive ("Clive of India") made an agreement with Jafar, who held his soldiers back at just the right moment, allowing Clive to defeat Siraj. As a reward, Jafar was made the new Nawab of Bengal, although this arrangement was not always comfortable and he was sacked for a brief period for displeasing his new masters.

The Battle of Plassey, which took place in 1757, is sometimes used as a start date for British rule in India, making Jafar's betrayal particularly significant for the country's history. According to India Today, Jafar is so hated that one of his modern descendants has complained of being openly mocked and harassed for his family name.

The Rosenbergs

Julius Rosenberg was a key member of a highly successful communist spy ring in the U.S. Among other things, he helped infiltrate the Manhattan Project in the 1940s, passing on information that might have helped the Soviets develop their own nuclear weapons. Both Julius and his wife, Ethel Rosenberg, would pay for their activities with their lives, sent to the electric chair at Sing Sing prison.

From a young age, the Rosenbergs were both committed communists. At their trial, it was alleged that Julius had taken an interest in communist ideas in college, while Ethel had joined the Young Communist League as a young woman. Although declassified documents published in 1995 show that Julius was undeniably guilty, it is less clear if Ethel really was a spy. Some people believe that David Greenglass and his wife Ruth, who were also involved in the spy ring, fabricated evidence against Ethel as part of a plea deal. The Greenglasses cooperated with the authorities and escaped the chair, while the Rosenbergs stayed stonily silent — and fried.

Those in favor of executing the Rosenbergs felt that the nature of the secrets they passed on made their crimes particularly bad. President Dwight D. Eisenhower, for example, argued that the sentence was just, stating, "I can only say that, by immeasurably increasing the chances of atomic war, the Rosenbergs may have condemned to death tens of millions of innocent people all over the world" (via History).

The Cambridge Five

The Cambridge Five were the British equivalent of the Rosenberg spy ring — a highly educated group of young men who were drawn to communism in the 1930s and wound up working for the Soviet Union. Kim Philby (pictured), Guy Burgess, Donald Maclean, Anthony Blunt, and a fifth man who was probably John Cairncross, were all recruited by the Soviets while at Cambridge University. Each member went on to become part of the British establishment in some way, working at the Foreign Office, MI5, and MI6.

Maclean in particular passed on valuable U.S. nuclear secrets to the USSR, while the others handed over hundreds of classified documents. Their success is all the more remarkable given that stolen KGB files provided by a Soviet defector in the 1990s describe both Maclean and Burgess as blabbermouths and heavy drinkers who regularly came close to blowing their cover.

The revelation that the men were spies was so embarrassing to Britain that although Burgess and Maclean's activities were uncovered in 1951, the affair was hushed up for many years. Declassified government files reveal that senior officials were concerned that they might not have enough evidence to prosecute the men, and that the revelations could cause a scandal in America. The members of the group were never actually prosecuted, although Blunt lost his knighthood in his winter years. Maclean, Burgess, and Philby all escaped to the Soviet Union, where they were left undisturbed.

Brutus and the other men who killed Caesar

Julius Caesar was by no means a saintly figure. A leading populist politician in the Roman Republic, he had himself declared dictator for life in 44 B.C. In response, a group of disgruntled senators stabbed him to death on the Senate floor not long afterward. While the senators involved would doubtless argue they were trying to protect the Republican system from tyranny, the assassination of Julius Caesar still makes many of us uncomfortable because among the conspirators were men who claimed to be Caesar's friends and allies.

Marcus Junius Brutus is usually cast as the worst of the lot, and for good reason. Brutus was the son of Caesar's mistress, making him almost like a son to Caesar himself. Worse still, he had been forgiven by Caesar once before for supporting his enemy Pompey Magnus in the recent civil war. Although Caesar did not say "Et tu, Brute?" as he died (a la William Shakespeare), according to the ancient historian Suetonius, in his "Twelve Caesars," he did turn to Brutus and say, "You too, my child?"

Still, Brutus is not the only conspirator who deserves to be labeled a sniveling traitor. Several men in the group had fought with Caesar on his campaigns before they murdered him. Decimus Junius Brutus Albinus, for example, is a particularly unlikable figure, having both backed Caesar in the civil war and been raised to prominence by him. When Decimus did not receive enough attention for his recent victories, he joined the other conspirators and stabbed his friend in the back (or more literally, the ribs).

Diarmait Mac Murchada

In the High Medieval Period, Diarmait Mac Murchada was one of many petty kings to rule over Ireland. He inherited the throne of Leinster in a volatile time in Irish history, and he quickly became entangled in a series of deadly power struggles. An all-around bad guy according to medieval sources, Mac Murchada was known to have killed and/or blinded 17 Irish chiefs, and he once abducted an abbess, killing at least 140 people and burning down her abbey in the process.

Mac Murchada was one of several kings who strived to control the coveted city of Dublin. However, in 1166, he was overpowered by his enemies and forced to flee. Heading to Aquitaine to speak to the king of England, Henry II, he managed to get several Norman lords involved in his Irish squabble, essentially inviting them to invade Ireland.

With the help of Richard, Earl of Pembroke — an Anglo-Norman lord better known as "Strongbow" — Mac Murchada reclaimed Dublin, although he died shortly afterward. His personal ambition would have enormous repercussions for Ireland, sacrificing Irish sovereignty for centuries to come. Henry II declared his sovereignty over Ireland, and the English would be exceedingly difficult to dislodge ever after.

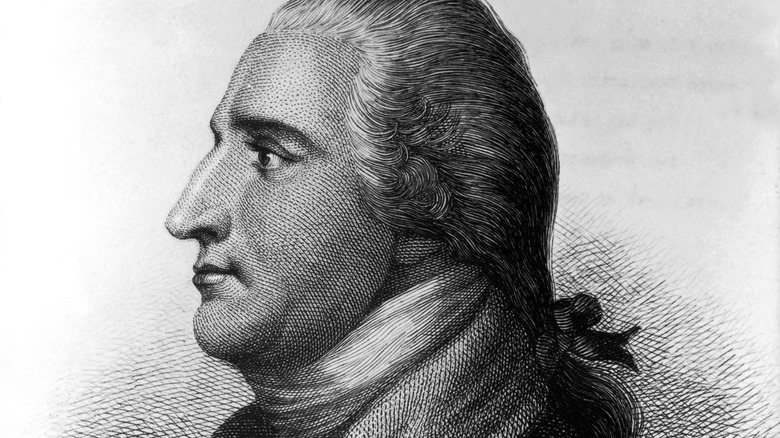

Benedict Arnold

Every American schoolchild knows the story of Benedict Arnold, the man who betrayed the American revolutionaries to the British (or at least tried to). Before he turned traitor, Arnold distinguished himself as a good soldier during the American Revolution. He achieved some notable successes at Fort Ticonderoga, for example, and helped outfox the British at Valcour Island. Nonetheless, Arnold felt he had been passed over by the high command and eventually agreed to switch sides to help Great Britain. Leading up to his betrayal, he was summoned to court on a list of petty charges by patriot Joseph Reed, an ordeal that soured his relationship with the revolutionaries.

Some believe Arnold's wife may also have been a deciding factor in his betrayal. His second wife, Peggy Shippen, was from a family with loyalist sympathies. Arnold seems to have been very committed to the revolutionary cause before they met, so his genuine love for her may well have been a strong driving influence. The British also offered Arnold a lot of money, which the notoriously avaricious Arnold sorely needed to provide for his aristocratic wife.

Arnold's plot to surrender the fort at West Point failed in spectacularly short order. His middleman, John André, was caught with incriminating papers on his person, and Arnold was forced to make a run for it. He served out the rest of the war as a British officer, before retiring to Britain after the war.

Guy Fawkes

Following Henry VIII's Reformation, the U.K. went through a tumultuous period of religious upheaval. By the time James I came to the throne, England was truly Protestant, and Catholics had become a persecuted minority. Although some hoped James would change things, he too cracked down on Catholics, throwing all the priests he could find out of England. Committed Catholic Guy Fawkes was one of a number of men radicalized by this grim state of affairs. Taking matters into his own hands, he wound up embroiled in a plot to blow up James I and the Houses of Parliament.

After hatching their plan in the pub, the Catholic conspirators placed 36 barrels of gunpowder in the cellars under Parliament. An anonymous letter tipped off the authorities about the plan, and all 13 men were caught or killed. Today, people tend to only remember Fawkes from the group, because he was the one caught red-handed standing around with a packet of matches.

For centuries after his betrayal, Fawkes became Britain's punching bag, burned every year on the fifth of November for "Bonfire Night" (Guy Fawkes Day). Less invested in Catholic plots than in previous centuries, today many "Guys" are actually effigies of other unpopular figures from modern Britain. For example, according to Euronews, the disastrously short-lived Prime Minister Liz Truss was burned instead of the firebrand Catholic in Edenbridge in 2022.

Ephialtes of Trachis

Ephialtes of Trachis was a famous traitor from ancient Greece. Known for selling out the noble Spartans and their allies at the Battle of Thermopylae, Ephialtes gave up valuable information that led to their demise. Readers may know a different version of the story from the movie "300," which portrayed Ephialtes as a deformed Spartan warrior with a grudge — none of which is true.

During the Persian Wars, when superpower Persia looked poised to engulf the fragmented city-states of Greece, many Greek states banded together for a change, to fight their common enemy. The famous 300 Spartan warriors, along with a motley band of other Greeks, held back the Persian flood by fortifying the narrow mountain pass at Thermopylae. The tight gap diminished the Persians' numerical advantage and allowed the Spartans and their allies to hold for a surprisingly long time — that is, until local Greek shepherd and hated turncoat Ephialtes of Trachis told the Persian king that he could flank the army by taking another route, the Anopaia path, around them. According to Herodotus' "Histories", Ephialtes betrayed his countrymen simply because he expected a reward from the Persian king.

Ephialtes' advice turned out to be extremely useful and the Greeks lost in heroic fashion, with the Spartans, Thespians, and possibly the Thebans sacrificing themselves to a man while the other Greeks retreated. Ephialtes fled to Thessaly to avoid reprisal for his treachery. To the delight of the Spartans, he was eventually murdered by a man named Athenades for unrelated reasons. Thankfully the Greeks would win the war, if not the battle, despite the betrayal.

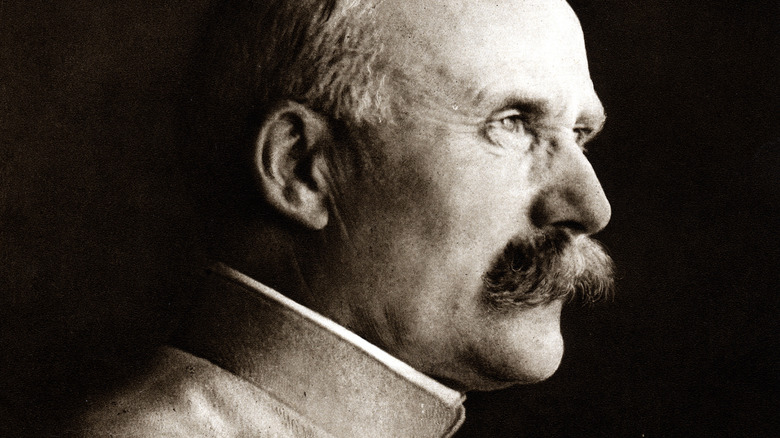

Henri-Philippe Pétain

Rarely has anybody's reputation taken such a steep nose-dive as that of French General Henri-Philippe Pétain. In World War I, Pétain was a decorated commander, famous for leading his troops to victory at Verdun. Years later he collaborated with the Nazis, becoming the head of the Vichy government.

At the end of the war, Pétain was condemned to die as a traitor, but President Charles de Gaulle commuted his sentence. Instead, he lived the remainder of his days on the prison island of Île d'Yeu, where he is now buried.

Some French citizens still admire Pétain, who made excuses after the war for his cooperation with the Nazis. While he was in charge of France, Pétain did secretly support the Allies in some ways. For example, he quietly ordered African French forces to join up with Germany's enemies in North Africa. Some also claim that he did his best to safeguard French Jews under the regime, although in truth his time in office saw the deportation, imprisonment, and death of thousands of Jewish people. Tense political arguments over Pétain's life are still ongoing in France today.