The Last Words Of Royals Before They Died

No matter what the time period or location they live, royals spend their lives used to getting the best of everything and, often, a level of power and authority that is not to be questioned. So when death finally comes for them, it must be quite a shock to the royal system that they can't just order it to go away, or at the very least ask for a VIP, comfortable passing, with complimentary dying champagne.

Perhaps then it's no surprise that many royals whose last words were recorded (more specifically, ones that are believed to be accurate) tend to be a bit, well, boring. Apparently, they didn't spend a lot of time thinking about appropriate last words for a king or queen when their time finally came. Those royals are not on this list. However, some royals who were surprised when death came did manage to say something funny, notable, or ironic. And other royals did give it some thought before their deaths, usually because they were told in advance they were going to be executed. In those cases, their last words can be an interesting insight into the royal psyche.

Everyone dies, but do royals die differently? Do they die better? Do they have good outro lines? Let's find out.

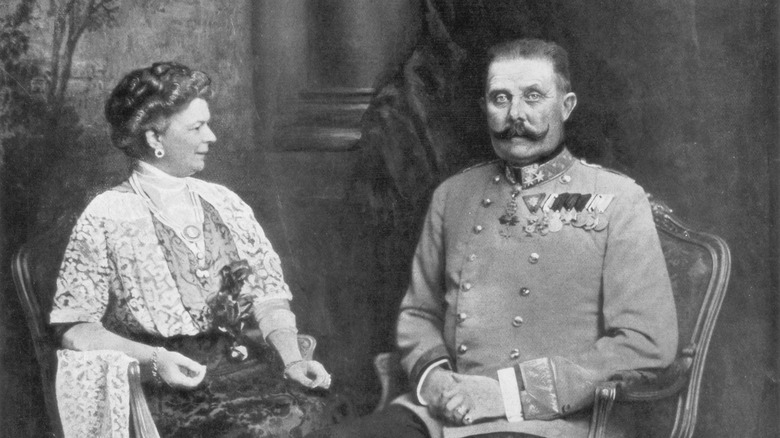

Archduke Franz Ferdinand

Franz Ferdinand is famously known as quite a good band, and also the Austrian archduke whose assassination in 1914 led directly to World War I thanks to a complicated web of European alliances.

The assassination was much more chaotic and had more victims than many might know. A group of Serbian radicals decided to kill the royal when he was in Bosnia and Herzegovina, which was then a part of the Austrian empire. The attack was actually conceived as a bombing, and indeed, a bombing was carried out. It did not get its intended target though — not knowing what it was, Franz Ferdinand actually swatted the small bomb away when he saw a projectile heading toward his wife, Sophie, who was also in the car. The resulting explosions did, however, wound many innocent victims who had come to see him drive by in his open car. After the explosion, the archduke actually got out to try and help those who were injured, before continuing on to his original destination.

Later that day, Franz Ferdinand changed his official schedule to go see the bombing victims in the hospital (none of whom had been critically injured). This time, the car drove past another member of the terror cell, Gavrilo Princip, who shot both the archduke and his wife. According to "Sarajevo: The Story of a Political Murder" by Joachim Remak, as the dying Franz Ferdinand was rushed away for help, he kept repeating, "Es ist nichts... es ist nichts...," which translates to "It is nothing."

Mary, Queen of Scots

As rulers of Scotland and England when they were still two separate countries, Mary, Queen of Scots and Queen Elizabeth I of England were natural rivals, even though they were also first cousins once removed. After years of political machinations in Scotland, Mary fled to England where she was locked up by Elizabeth. The English queen genuinely tried to avoid executing her cousin, but when Mary was implicated in a plot against Elizabeth, it was clear she was a danger to her throne and had to go. It was perhaps ironic Mary was sentenced to die by beheading, as Elizabeth's mother, Anne Boleyn, had also been.

Mary's final hours on February 8, 1587, were recorded in great detail. According to "Elizabeth and Mary: Cousins, Rivals, Queens" by Jane Dunn, a dean from the Church of England tried to get her to convert before her execution, but the staunchly Catholic Mary refused.

The 1923 book "Trial of Mary, Queen of Scots" records that she faced death bravely. While all her attendants were crying, Mary insisted she was about to be very happy. She wore bright red petticoats, clearly a commentary on her fate. She tried to get the whole thing over with quickly, laying her head on the block and repeating "In manus, Domine, tuas commendo animam meam," Jesus' last words in Luke 23:46 that translate to "O Lord, into Thy hands I commend my spirit." The first blow only injured her; the second took off her head.

George V

George V died in 1936, and for decades his death was put down to natural causes. In reality, as The New York Times reported in 1986, the king's doctor recorded in his notes that he gave the unconscious, already near-death man a lethal overdose.

Original reporting on George's final words was as sanitized as his cause of death, with the public told that, at the very end, George was still thinking about the state of the realm. No less than the then-Prime Minister Stanley Baldwin painted the picture: "...he did say to his secretary when he sent for him: 'How is the Empire?' An unusual phrase in that form, and the secretary said: 'All is well, sir, with the Empire,' and the King gave him a smile and relapsed once more into unconsciousness."

Later, the public, perhaps feeling those last words were a bit too pat, somehow started a rumor that the king's last words were actually "Bugger Bognor." Bognor Regis is a coastal town that was considered a good place for invalids to recuperate. The story was therefore that when it was recommended to the dying George he go there to get better, he told the individual what he thought of that idea. However, the same doctor's notes that revealed how the king really died also included a detail on his last words. A nurse injected him with morphine and as he lost consciousness for what would be the final time, he said, "God damn you."

Joachim Murat, King of Naples

Being one of Napoleon Bonaparte's best friends could be a lucrative position ... for a while, at least, until it all went wrong for the self-appointed emperor. One of his favorites was Joachim Murat, who Napoleon made king of Naples when he took over the island, which, at that time, was its own country. Normally, Napoleon appointed one of his siblings to run places; in Naples, however, he gave the crown to Murat in 1808, to whom he was not related by blood — only by marriage, since Murat's wife was Napoleon's youngest sister Caroline Bonaparte.

While Murat actually did some good things while in charge of Naples, politics in Europe was a whirlwind in the early 1800s. Murat lost his throne in 1815, and when he tried to take it back using the revolutionary military tactic of "not having an army," he was, unsurprisingly, apprehended. "The History of Napoleon Bonaparte" by John Stevens Cabot Abbott, published in 1904, wrote that he was sentenced to death by firing squad. Murat turned down a blindfold, then spoke to men aiming guns at him: "Save my face; aim at my heart."

An 1836 edition of "The Military and Naval Magazine of the United States" wrote that Murat was one of those from that time who had "died like men, like brave soldiers," comparing his and other "brave" deaths to the easy death of Napoleon in relative comfort, allowed to die a natural death on Saint Helena.

Empress Dowager Cixi

Once a concubine for China's Xianfeng Emperor, Tzŭ Hsi (usually Latinized as Cixi, pictured center) managed to overcome centuries of tradition and take power for herself — first alongside another former concubine in 1861, then on her own. It was unheard of for a female ruler to take control and, technically, according to "China Under the Empress Dowager" by J.O.P. Bland and E. Backhouse, there was a male emperor: Cixi's son became Tongzhi Emperor. But as he was only 5 years old at the time, power flowed through his mother. After her son died in 1875, Cixi simply placed different young male relatives on the throne in turn, so it was really she who stayed in charge for decades.

Cixi held on to power until her death in 1908. Considering how calculatingly and methodically she, as a woman, had gone after and consolidated power, Cixi's official last words were hypocritical, to say the least. Asked by those by her deathbed for her "official" last words, she said, "Never again allow any woman to hold the supreme power in the State. It is against the house-law of our dynasty and should be strictly forbidden." To be fair to Cixi, it was not women who were her greatest concern for the royal family; that would be eunuchs, since she added, "Be careful not to allow eunuchs to meddle in government matters. The Ming dynasty was brought to ruin by eunuchs, and its fate should be a warning to my people" (via The Atlantic).

Louis XIV

Of all the kings to ever king, perhaps none of them did it more regally than France's Louis XIV. He built the Palace of Versailles into the giant golden building tourists flock to today, put the hair bands of the 1980s to shame with his coif, and consolidated his already absolute power around himself despite being only 4 years old when he took the throne.

According to "A World of Paper: Louis XIV, Colbert de Torcy, and the Rise of the Information State," by John C. Rule and Ben S. Trotter, one thing Louis didn't do was say the most famous quote ascribed to him, "L'État, c'est moi," which translates to "I am the State." However, he made up for not saying something so on-brand with his final words. Louis' final years had been sad, with many of his relatives dying young, and a war that France didn't do very well in. But on his deathbed in 1715, aged 76, Louis still understood his place and his purpose in life, saying, "Je m'en vais, mais l'État demeurera toujours," meaning "I am leaving, but the State will always remain."

They were virtually perfect last words for an absolute monarch who had effectively made himself the center of France's world. However, considering he thought of the State firmly in terms of the monarchy, he was also wrong, since in 1789, a couple of King Louis' later, the French Revolution ended the rule of the Bourbon royal family.

Elisabeth, Empress of Austria

Empress Elisabeth of Austria (and later the Queen of Hungary), popularly known as Sisi, was set up to have a perfect life, at least on paper. She was stunningly beautiful and came from a wealthy, important family. When Emperor Franz Joseph, eight years her senior, met Elisabeth for the first time, he fell in love at first sight and refused to marry anyone else. So, in 1854, Elisabeth became empress of one of the most powerful countries in Europe.

Everything after that was pretty much terrible. Her mother-in-law hated her. The aristocrats and others in her social class hated her. Her only son, Crown Prince Rudolph, died in a murder-suicide in 1889 along with his lover. Elisabeth's own death would be just as violent.

In 1898, the empress was in Switzerland, traveling under a fake name with her friend and attendant Countess Irma Sztáray, according to "Elizabeth, Empress of Austria and Queen of Hungary" by Carl Küchler. However, her real identity got out, and Italian anarchist Luigi Luccheni decided to kill her. While waiting to board a ship, he got close enough to Elisabeth to stab her in the chest. As Elisabeth collapsed, the countess didn't even realize anything was wrong, thinking the empress had only fainted. She was rushed onto the boat where she collapsed again. Finally seeing blood on her clothes she asked, bewildered, "What has happened?" She then lost consciousness and died a few hours later.

George IV

Considering how he lived, it's frankly astonishing that George IV survived as long as he did. He drank and ate to such a degree that, by the end of his life in 1830, he refused to go out in the society he loved because of how large he had become. According to "The Age of Scandal" by T.H. White, he was also losing his sight and, to some extent, his mind. The 1926 biography "George the Fourth" supports this last point, saying that while the king had always been fond of exaggerating, as he slowly died over the course of weeks, the fantasies he told his visitors about his achievements became more ridiculous, including that he'd played a key role at the Battle of Waterloo, despite having never left England during the conflict with Napoleon.

George's death was long and drawn out, so much so that even his former morganatic (meaning non-royal, and unacknowledged) wife Maria Fitzherbert had to time learn he was gravely ill, travel to London, and write him, hoping to be called to see him before he died.

Based on his last words, it's clear that George's doctors downplayed just how dire a situation the king was in, or at least how much time he really had left. On June 26, he suddenly woke up after sleeping a full 24 hours and shouted, "This is death. Oh God, they have deceived me," then died.