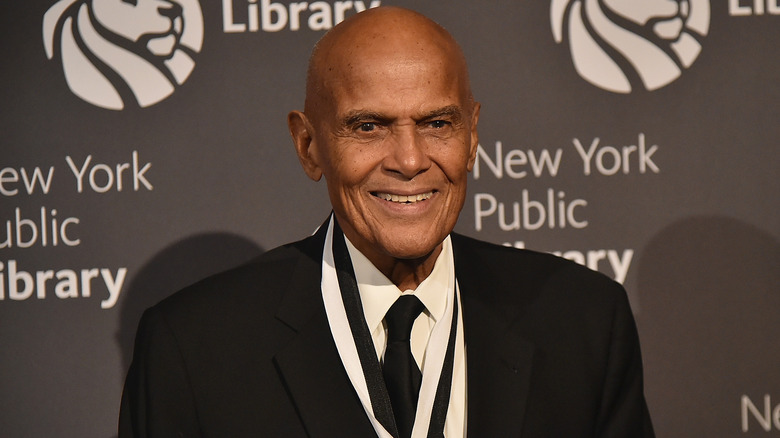

The History Of Harry Belafonte's Famous Day-O

When Harry Belafonte released "Calypso" in 1956, he had no idea that either the album or the much-sung single "Day-O" would be a hit. In fact, as The New Yorker quotes his 2011 autobiography "My Song: A Memoir," he didn't even know that "Day-O" was going to be a single. He mostly remembers arguing with the record label about the cover — featuring "a big bunch of bananas superimposed on my head" — which he found more than a bit ridiculous. As it stands, "Calypso" was the first full-length album in history to go platinum. "Day-O" itself — known by its alternative title "The Banana Song" — went on to hit No. 5 on the charts. And so Belafonte forever set into motion voice after voice crying "daaaaaay-o!" in an attempt to jog people's memories about what song they're yammering about.

As for "Day-O" itself, many people might pick up on its general Caribbean vibe even without being able to pinpoint exactly why it feels that way. The name of the album provides a clue: calypso. As The MIT Press Reader explains, calypso isn't a genre of music but a loose collection of rhythmic musical patterns derived from West Africa by way of Trinidad. Songs often describe bawdy tales using double meanings. Harry Belafonte, though, wasn't Trinidadian — no matter how his ethnic and racial heritage spanned the globe. He grew up in Harlem but spent time as a child with his grandmother in Jamaica. His time there inspired "Day-O."

Tallying bananas at the end of the day

To make the point clear, Harry Belafonte didn't write "Day-O." His version is a cover of a much older folk song first recorded in 1952 by Trinidadian musician Edric Conner. You can listen to this very different, much slower and mournful version on YouTube, titled "Day De Light." Belafonte didn't write the lyrics to his version, either. Song Facts says that Caribbean composer Irving Burgie and novelist William Attaway modified the lyrics for Belafonte, as well as wrote most of the lyrics on "Calypso." In other words, Belafonte's "Day-O" remixed an existing song with revised lyrics, and Belafonte himself provided the stage presence and voice.

As for the lyrics, we've got the well-known, "Day-o, day-ay-ay-o / Daylight come and me wan' go home" line, and the famous "Come, mister tally man, tally me banana" line that folks might remember. Without knowing any other lyrics, these lines tell us everything we need to know about the meaning of the song: It's about laborers at the end of the day waiting for their workload to be counted. The tally man is the guy who counts the bananas from the day's work. As The New Yorker says, the tune for "Day-O" likely spans back to "the turn of the 20th century" as a call-and-response song composed of two sets of singers. This is exactly what the composition in Belafonte's version does. His version also ties the period-accurate tune to period-accurate labor.

A song of joy, sorrow, and community

For such an ostensibly simple song, "Day-O" conveys potent and nuanced emotions that just might account for its lasting success. It's wistful, joyous, a bit impatient, and laced with longing. Basically, it's precisely the song that a bunch of banana-collecting laborers would sing to cope with their fatigue and exhaustion. If you remove the lyrics from the music, the composition is much less sad than the lyrics imply. Such is the experience of being on a beautiful island while having to tend to the toughness of everyday life.

This is more or less the point, as The New Yorker discusses. Harry Belafonte himself felt pulled between multiple worlds. As a multiethnic and multiracial person, he said, "I wasn't even a full-fledged Jamaican, or a black from Harlem with full Afro-American roots." He just knew what it felt like to be there in Jamaica in the small mountain community of Aboukir in his grandmother's wooden house. This is clearly the feeling he's tapping when singing "Day-O" — sensing and striving for freedom but being unable to attain it — as we can see in performances like a 1960 rendition available on YouTube. In this way, Belafonte was perfectly situated for his role in the U.S. Civil Rights movement as an advisor to Martin Luther King Jr., financial donor, and more.

Sadly, Belafonte died of congestive heart failure on April 25 in his Manhattan home. He is survived by his wife Pamela and four children.