How Harlem's Apollo Theater Changed America's Entertainment Landscape

Up on 125th Street in the center of New York City's Harlem district, a bright red and yellow marquee lures entertainers to it like moths to a flame. This is the legendary Apollo Theater, which has been a centerpiece in the development of American entertainment for the past century.

The influence of the Apollo cannot be underestimated — particularly its impact on the development of Black culture in the United States. The list of performers who have held court in the approximately 1,500-seat venue is a cavalcade of the most notable of notables of entertainers of color, including Ella Fitzgerald, James Brown, Lena Horne, Billie Holiday, and B.B. King. As the venue gained in fame, white performers also gravitated toward the Apollo, probably starting with Buddy Holly in 1957. But these successes at the Apollo are more the exception than the rule. Many performers have been burned at the Apollo by its discerning and fiery audience.

Just how the Apollo became so dominant as an entertainment influencer is a fascinating tale, not least because in its beginnings the Apollo seemed the opposite of a place that would become a cradle of the Harlem Renaissance. But a pioneering influence it did become in changing and molding America's entertainment landscape.

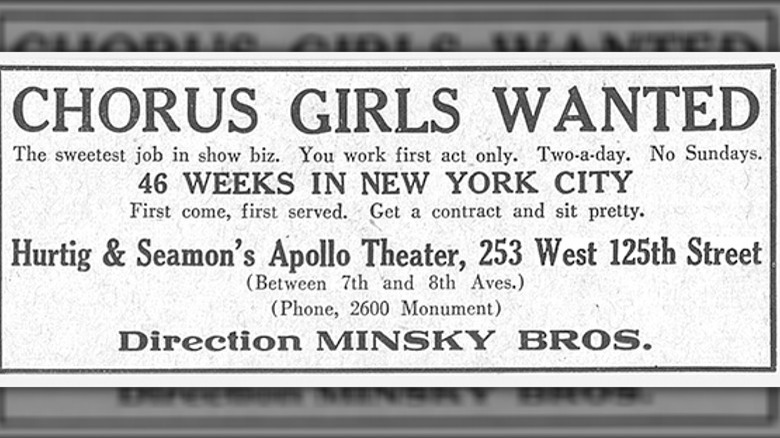

The Apollo started as a burlesque

The early history of the Apollo Theater is as complex as a Sammy Davis Jr. tap dance routine. The building at 253 West 125th Street started life in 1913 as an Irish music hall of all things. But a year later, the building had transformed into "Hurtig and Seamon's New Burlesque Theater." The theater showed mainly white, female dancers (like Fanny Brice) who titillated audiences with sexy performances of which Harlem World tells us that Jules Hurtig and Harry Seamon were renowned. The theater was also segregated, with a limited number of African-American attendees being relegated to the balcony. Even though they operated on a 30-year lease, the business was taken over by the rival burlesque producer Bill Minsky in 1928, at which point he renamed it the 125th Apollo Theater.

In the early '30s, New York Mayor Fiorello La Guardia effectively shut down burlesque entertainment in the city. Shortly thereafter the theater came under the ownership of Sidney Cohen, who could rightly be called an early entertainment mogul since he was president of the Motion Picture Theater Owners of America and controlled the popular Roxy and Gaiety Clubs.It was Cohen who changed the entertainment format into what is revered today — a showplace for up-and-coming African-American music, dance, and comedy.

Sidney Cohen desegregated the Apollo

In the early 20th century, Harlem was largely a white neighborhood. This changed as African Americans, seeking to escape the Jim Crow South, migrated to Northern cities. Harlem drew African Americans of all backgrounds who forged their own culture in the Harlem Renaissance.

In the face of Fiorello La Guardia's crackdown, Sidney Cohen adopted a different business tactic. His Apollo Theater would be focused on the Harlem community and provide live entertainment for the African Americans who lived there. His Apollo would take the form of a variety show in which audiences would see newsreels, a film, and up to seven live performances in what is called a revue. Almost anything could be seen at the Apollo — from animal performances to acrobatics to big bands. It would follow this format for decades to come.

Finally on January 26, 1934, with Morris Sussman as manager, the Apollo opened its doors to history to admit an interracial audience. Its first performance was "Jazz a la carte" emceed by Ralph Cooper and featuring Benny Carter and his orchestra. In support were the "Gorgeous Hot Steppers," an entirely Black chorus line.

It brought us Amateur Night

One of the early innovations of the Apollo Theater happened in 1934. The Apollo got off to a rocky start and was about to go under. In response, Roy Cooper introduced "Ralph Cooper's Amateur Night." This weekly program offered a platform for residents to compete, while audience members quickly developed an appetite for booing the unworthy. Meanwhile, in order to gently remove substandard performers, Cooper employed a costumed stagehand to escort losing contestants offstage, known as the "Official Executioner."

The real attraction of Amateur Night was not just money, but the prospect of glory. Those who won were invited back to join the next week's show. One early winner was Ella Fitzgerald, who debuted on November 21, 1934. Fitzgerald was originally going to do a dance routine but at the last moment decided to sing. It was a wise choice.

Amateur Night launched the careers of other numerous stars, including Billie Holiday, Luther Vandross, and Gladys Knight. Of course, the vast majority of Amateur Night contestants were losers, but there was always hope. In fact, a curious tradition developed. In Harlem, there was an elm tree where out-of-work actors gathered called the Tree of Hope. It ingratiated itself so much into entertainer folklore that performers like Bojangles Robinson would go there and rub it for luck. By 1934 the tree was gone, but not hope. Its stump was removed to the Apollo where contestants touch it for luck before going on stage.

It transformed into a center of African-American culture

Sydney Cohen did not see whether the new direction of the business venture would be successful since he died of a heart attack in 1935. The Apollo then was bought by Leo Brecher and Frank Schiffman, whose family would remain the owners for decades. They had owned the Apollo's closest rival, the Lafayette Theater, which was also desegregated. After buying the Apollo they continued Cohen's policies, as well as actively recruited people of color as workers. As a result, the Apollo flourished and became a centerpiece of the Harlem Renaissance. This was important since it made the Apollo clearly stand out from so many other entertainment venues in which people of color were discriminated against.

The Apollo focused on Black audiences with Black entertainers. This was a marked difference from other venues, such as the famous Cotton Club, which featured Black entertainers who performed for exclusively white audiences — barring African Americans from the venue. It also was one of the top marquees in the country that freely allowed American entertainers from Marvin Gaye to Richard Pryor to develop their skills. It also developed a reputation for allowing entertainers to push the envelope in content that might not be as tolerated in other theaters. Author Gladys L. Knight in her book "Pop Culture Places" rightly points out that "Entertainers whose careers were launched at the Apollo would go on to influence the world."

It was a venue for innovative new talent

To fully appreciate the importance of the Apollo it must be placed into historical context. Virtually all live entertainment in America was segregated, and much of it played to racial stereotypes. The Apollo offered a unique high-end oasis where Black performers could play for Black audiences. As such, it was one of the most important stops of the so-called "chitlin circuit." This was a series of venues across the country that catered to Black audiences that included nightclubs, theaters, and dance halls. Among the most preeminent venues were Chicago's Regal Theater, Washington, D.C.'s Howard Theater, and of course the Apollo.

Many of the most prominent African-American performers of the 20th century won their fame going through this circuit and then coming out on top at the Apollo. This includes the legendary Billie Holiday, who made her first appearance at the Apollo in 1934. In her memoir, "Lady Sings the Blues," she recounted how she was paid $50 a week for her appearances in Harlem. She was thrilled not just for the money but because "Uptown, the Apollo was what the Palace was downtown."

The Apollo had music pioneers

The Apollo shaped entertainment through the cavalcade of pioneering performers who held court there. Duke Ellington, Count Basie, and Dizzy Gillespie were all featured performers at the venue in its first years. Another was Louis Armstrong who stopped at the Apollo in the summer of 1935 after his new manager pushed him to book in the top clubs. Of his performance, the New York Amsterdam gushed (via "Heart Full of Rhythm," by Ricky Riccardi) that Armstrong was "at the peak of his career and that he has given perfect enjoyment to the record audiences which turned out to see and hear him this week."

Another pioneering group that is not as well-known today was the International Sweethearts of Rhythm. They were the first racially integrated women's jazz band and made multiple appearances at the Apollo through the 1940s. They were one of the hottest acts to dominate the chitlin' circuit of the World War II era and demonstrated racial equality among whites, Blacks, and Latinos in an age when it was absent. In 1944, The Apache Sentinel reported on the excitement caused by the group, writing "[they] boast some of the hottest swing artists in the music world. Their harmonics are classed as superb and to watch Directress Winburn draw the melody from this group of feminine musicians is a thrill in itself."

The Apollo swung

The Apollo clearly influenced many forms of music, with one of the most prominent being swing of the 1930s. New York was the capital of "Black swing," and the capitol of this capital was the Apollo. Swing legends such as the "maestro" Duke Ellington and Count Basie are all associated with the venue.

Duke Ellington began performing at the Apollo in the 1930s and was a regular performer there throughout his life. A reporter from the Boston newspaper, The Guardian, covered Ellington's Apollo show in 1954 and opined that the band seemed to be falling out of the times of music trends even though they were flawless. Ellington quipped, "Nothing got me into trouble but my good taste."

Basie's debut at the Apollo in 1937 was nerve-wracking. According to "Count Basie," by Joanne Mattern, even though he was to appear with Billie Holiday, who had already performed there, he felt that his professional reputation was on the line. This was not helped by a teasing stagehand while he waited to come on stage. But he need not have feared — he was Count Basie after all. When he played "I May Be Wrong" his path to becoming a legend was cleared, notes record producer John Hammons in Ted Fox's "Showtime at the Apollo."

The Apollo had soul

Swing is just one genre of music, but the Apollo's genius was in the way in which it embraced fresh talent across music genres. Aside from swing, jazz and blues were predominant forms of music played at the Apollo in its early years, but it truly was ecumenical. Almost every major form of American popular music from R&B to bebop to gospel was tested at the Apollo. In fact, as mentioned the real test at the Apollo was its audience who would readily boo offstage any performer that didn't meet their standards. This is why many veteran performers who had already established their careers, such as Josephine Baker and Eartha Kitt, played at the Apollo since they wanted to prove that they were truly successful and not a one-hit-wonder.

One of the artists who never failed to please the audience and one that became synonymous with the Apollo was the "Godfather of Soul" James Brown. His career was just lifting off when he appeared at the Apollo in 1962. The next year a recording of his performance, "James Brown Live at the Apollo," rocketed Brown to superstardom. This album was ranked 25th on Rolling Stone's list of the 500 greatest albums of all time, stating that it is "perhaps the greatest live album ever recorded ... Live at the Apollo is pure, uncut soul."

The Apollo danced

No less influential were the Apollo's dance performances. The Apollo's prestigious platform brought popular cache to new dances. For example, "History of Dance," by Gayle Kassing, tells us the African-American dance the "black bottom" displaced the Charleston as a popular dance after its appearance during the 1926-1927 showing of "Scandals," a music revue that highlighted it.

Then there were the stars. The 1930s featured tap dancers such as Bill "Bojangles" Robinson and the Berry Brothers. Saxophonist Andy Kirk opined in "Steppin' in the Blues," by Jacqui Malone, that playing backup for a dancer like Robinson at the Apollo was way different than at a pedestrian dance hall "because in a dance hall the dancers had to dance to your music. At the Apollo, with a star like Bojangles, we had to play music for him to dance to."

When dance performances were held at the Apollo the audience's famous finickyness grew acute since it was filled with dancing professionals. The dancer "Sandman" Sims recounted, "Up in the balcony, dancers, and the first six rows, you saw nothing but tap dancers, wanta-be tap dancers, gonna-be tap dancers, tried-to-be tap dancers. That's the reason a guy would want to dance at the Apollo." One of the legendary dancers of American entertainment, Sammy Davis Jr., first appeared at the Apollo in 1939 and would make many later appearances inspiring future generations of famous dancers, including Gregory Hines, who told met Davis in the Apollo in 1956 when he was 10, as per Jet Magazine.

The Apollo joked

The Apollo's influence on comedy is considerable since it provided a top venue for Black comedians. Some of the big comics of the early years were Dewey "Pigmeat" Markham, Tim Moore, and John "Spider Bruce" Mason. Pigmeat was most known for his "Here comes da judge" bit, which achieved widespread fame through its later appearances in 1968 on the television program "Laugh-In." Pigmeat was truly an Apollo staple, who played at that theater more than any other act. Pigmeat was edgy for his day, as shown in his "Lovemaking Bureau" sketch. These routines were far different than the earlier minstrel performances that played to stereotypes. Mel Watkins writes in "On the Real Side" that "Apollo comedians were beginning to infuse their humor with perceptions and jokes reflecting the more aggressive mood of the Depression-besieged black masses."

The Apollo gave liberties to African-American comedians to push the envelope. For example, "Icons of Black America," by Matthew C. Whitaker, tells us that Timmie Rogers was a popular comedian in the late 1950s and was the first African-American comedian to wear a tuxedo during his act. This was taboo since, at the time, Black comedians typically wore outlandish outfits stemming from minstrel days. Rogers was apparently fired for doing such a thing by a white manager earlier in his career. These steps led to further envelope pushers, such as Richard Pryor, who never shied away from expletive-laden routines that touched on racial divides in America.

It went beyond theater

The Apollo's influence went beyond those who attended its events in person. This is best demonstrated when the theater launched the television series, "Showtime at the Apollo," in 1987. This program used the format of Amateur Night to great success, with its first run ending in 2007. The television show presaged other talent search programs such as "American Idol" or "Star Search."

In total, "Showtime at the Apollo" in its original run had 1,093 episodes and was a staple of weekend television. It only ended after members of the production team left after a labor dispute and established their own show. However, you can't keep a good TV concept down. Fox has lately revived the series with Steve Harvey as the host. In its description, Fox states, "Featured in the series are elements from the Apollo's legendary Amateur Night –- the long-running, live talent competition, now in its 82nd year -– which provides a platform for up-and-coming artists to perform in front of the toughest audience in the world."

The Apollo is a landmark

The Apollo is not just a figurative landmark in the development of American entertainment — it is a literal one. By the 1970s the theater was in decline. General urban decay and crime had made the Apollo less attractive to patronize. In fact, in 1975 a shooting occurred during a Smokey Robinson performance. In the late '70s the Schiffman family shut down the venerable theater after declaring bankruptcy and tried to sell it, although occasional programs were still held. It was eventually bought by the Harlem Urban Development Corporation. It seemed like the days of the vibrant venue were done.

However, a revival was coming. In the early 1980s the Apollo became a national and city landmark. In 1984 it opened its doors again, this time under the control of a nonprofit organization. It also received a $20 million renovation in 1988. In 1992, the Apollo Theater Foundation was created to manage the landmark. As for the theater, it was given as a gift to the people of Harlem. Its mission today is a direct echo of how the theater had and still is changing America's entertainment landscape: "The Apollo is a commissioner and presenter; catalyst for new artists, audiences, and creative workforce; and partner in the projection of the African American narrative and its role in the development of American and global culture."