Songs That Are Said To Be Cursed

Music often offers relief from the grind of daily life. It can serve as a much-needed escape, set the mood for a memorable movie scene or epic party, or act as a soothing friend during times of need. And it goes deeper than that. Studies have shown that music can help treat anxiety, reduce stress and pain, combat depression, and even restore memory function, according to Medical News Today.

In fact, it has such strong ties to our emotional well-being that music therapy has become an effective form of psychological treatment, as reported by Psychology Today. This should come as no surprise to anyone who has an anthemic "power song" — like Queen's "We Will Rock You" or Lizzo's "Good as Hell" — that can raise them up from the depths of despair or help them crush that last set at the gym.

But, unfortunately, not all songs bestow blessings and benevolence. Given the tremendous power that music has over the human psyche, it's no wonder that many believe that there are songs out there capable of inflicting harm rather than promoting happiness, emotional peace, and productivity. From bad luck ballads to karaoke misadventures to hand-me-down hexes, here are a few of the songs that are said to be cursed.

Without You – Badfinger

A legacy of tragedy began in 1970 when Peter Ham and Tom Evans — both members of the Welsh band Badfinger – merged two despair-laced songs about their respective relationship woes into a single heart-wrenching ballad called "Without You." It seems that they infused more sadness than one song could bear. Signed to Apple Records and mentored by The Beatles, Badfinger was poised to become the next great rock band. But, instead, everything fell apart.

Apple Records crumbled after The Beatles disbanded, leaving Badfinger adrift. Desperate, they signed themselves over to the management of American fraudster Stan Polley. Lost in the shuffle of the foundering label, the band fell victim to Polley's criminal mismanagement, which left them practically penniless despite having several hit songs. In the midst of this chaos, singer-songwriter Harry Nilsson heard the band's then-obscure song, "Without You," at a friend's house.

Nilsson loved the song so much that he recorded his own version — though, pushed by his producer to sing at the upper limits of his vocal range on an arrangement he despised, he quickly grew to hate it. Nonetheless, it became an international hit for him in 1971. Ham and Evans, meanwhile, saw little success from their creation and remained mired in financial and legal struggles. As a result, both died by suicide at young ages. The song's curse seemingly struck again when singer Mariah Carey covered "Without You" in 1994. Just days before her chart-topping version debuted, Nilsson died of a heart attack.

If you or anyone you know is having suicidal thoughts, please call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline by dialing 988 or by calling 1-800-273-TALK (8255).

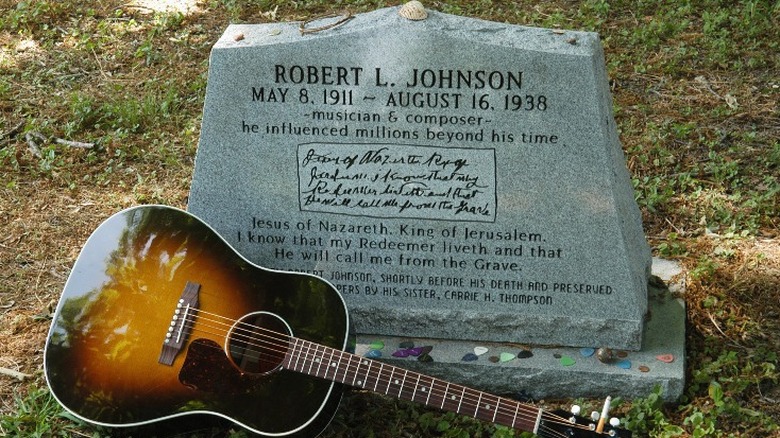

Cross Road Blues – Robert Johnson

Born into a Black family in 1900s Mississippi, legendary blues musician Robert Johnson lived a hard life but found solace in music. Eschewing the life of a plantation worker, he eked by as a musician and married his sweetheart. But his wife's religious family never approved of his chosen trade. In fact, when she died in childbirth, they attributed the tragedy to his affiliation with "the devil's music."

Johnson then devoted himself wholeheartedly to the blues, returning to the scene with seemingly supernatural musical abilities. According to music journalist Paul Trynka in his book "Portrait of the Blues," Johnson told fellow blues musician Son House that he had met a dark man at a crossroads who had tuned his guitar for him — a common euphemism for selling one's soul to the devil. Johnson faced hardships all the way up to his untimely and painful death by poisoning, and many attribute his life of misfortune to a powerful curse brought on by his devilish pact.

What's more, the curse allegedly lives on, with the so-called "Crossroads Curse" bringing tragedy to anyone who covers Johnson's 1936 song "Cross Road Blues." Both Robert Plant and Eric Clapton lost young sons after covering it, members of Lynyrd Skynyrd and the Allman Brothers died in accidents after performing it, and Kurt Cobain was considering recording it before dying by suicide. The curse even seemed to impact John Mayer, who covered the song shortly before falling out of mainstream favor.

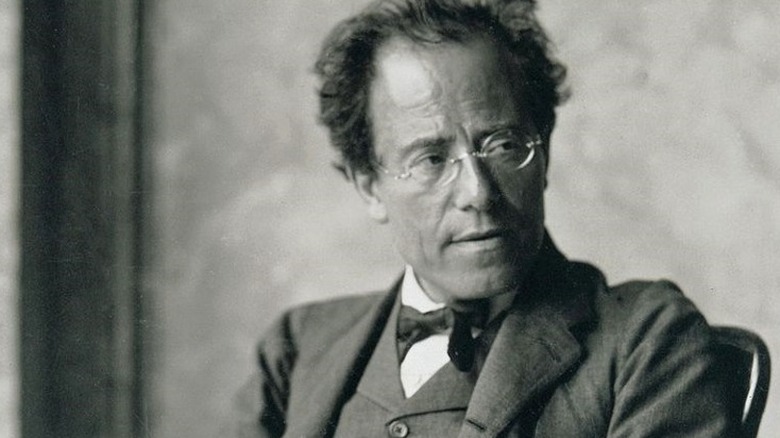

The Ninth Symphony – Any Composer

Song curses aren't just reserved for "the devil's music." In the 19th century, many classical musicians believed in the dreaded "Curse of the Ninth," in which composers were fated to die after completing their ninth symphonies. And it wasn't a baseless fear. Ludwig van Beethoven, Franz Schubert, Ralph Vaughan Williams, and Antonín Dvořák all died after their ninths. But one ultra-superstitious composer — Gustav Mahler — attempted to defeat the curse.

When writing his ninth piece of music, Mahler sought a semantic loophole and avoided calling it a symphony, though it technically was one. Unfortunately, the curse wasn't fooled. While composing his 10th symphony in 1911, he was stricken with pneumonia and died before completing it. Composer Arnold Schoenberg later waxed poetic about the curse in his book, "Style and Idea." "It seems that the Ninth is a limit," he wrote. "He who wants to go beyond it must pass away. It seems as if something might be imparted to us in the Tenth which we ought not yet to know, for which we are not yet ready."

Of course, many composers, including Mozart, escaped the curse unscathed. But trepidation survived into the modern age. "Everyone is afraid to do a Ninth Symphony," composer Philip Glass admitted to the Los Angeles Times shortly after debuting his own in 2012. As a precaution, Glass composed his ninth and 10th symphonies together. His trick worked better than Mahler's.

My Way – Frank Sinatra

Oddly enough, Ol' Blue Eyes' 1969 self-confidence anthem "My Way" is considered a song of ill-repute in the Philippines. In fact, the song incites such rage there that it inspired a slew of murders known as the "My Way Killings" at karaoke bars, which are highly popular in the Philippines. The anger mostly centers around how particularly awful the song sounds sung out of tune (which, if you're familiar with karaoke, is kind of a common phenomenon).

In one notable incident, a man named Romy Baligula was belting out "My Way" at a San Mateo karaoke bar in 2007 when security guard Robilito Ortega hollered at him that he was badly off-key. When Baligula continued singing, Ortega whipped out a gun and shot him dead. At least five other similar killings have taken place, with many lesser "My Way" infractions ending in violent fistfights.

As for why this song specifically rubs people the wrong way, many point to its cocky lyrics. "'I did it my way,' it's so arrogant," Butch Albarracin, the owner of a Philippines' singing school, told The New York Times. "The lyrics evoke feelings of pride and arrogance in the singer, as if you're somebody when you're really nobody." Others claim that the general machismo-related aggression prevalent in Filipino culture is to blame, and "My Way" just happens to be a popular choice for karaoke singers. Or, at least, it was: The accursed song is now banned at many karaoke bars.

Gloomy Sunday – Rezso Seress

Rezső Seress' somber 1932 piano ballad was originally titled "Vége a Világnak," Hungarian for "The World Has Ended." Inspired by a bad breakup, it was already a pretty glum song. But it was the version with lyrics by poet László Jávor, which describe a man suicidal after his lover's death, that caught on and became known as "The Hungarian Suicide Song."

The song was translated into English and later famously covered by Billie Holiday as "Gloomy Sunday" in 1941. But along with its popularity came a troubling problem: A shocking number of people who heard it ended up taking their own lives. Hundreds of suicides were bizarrely linked to the song, with one girl even found clutching its sheet music. In response, many networks banned it.

Tragedy also befell the song's creators. Holiday died at age 44 in 1959, and, years later in 1968, its original composer, Seress, died by suicide. Speaking about his creation with Time Magazine in 1936 (via "You Are What You Hear" by Harry Witchel), Seress lamented: "This fatal fame hurts me. I cried all of the disappointments of my heart into this song, and it seems that others with feelings like mine have found their own hurt in it." While all of this is certainly disturbing, a 2007 article published in Omega (Westport) notes that the increase in 1930s suicides likely had more to do with the ongoing Great Depression than the song. Still, listen at your own risk.

If you or anyone you know is having suicidal thoughts, please call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline by dialing 988 or by calling 1-800-273-TALK (8255).

Music Must Change – The Who

As the British rock band The Who learned, some song curses are quite selective with their victims. According to singer Roger Daltrey in a 2015 interview with Howard Stern on Sirius XM, the trouble began when drummer Keith Moon couldn't get the beat right on a song called "Music Must Change." Moon's unconventional style wasn't meshing with the song's standard time signature. He was also struggling with severe addiction issues.

As a result, the band ended up hiring a session musician to record drums for the song, which was released on 1978's "Who Are You." Then, on September 7 – just a month after the album's release — 32-year-old Moon died of an accidental overdose of the sedative Heminevrin, which he had been taking in an effort to quit drinking. Following his tragic death, the remaining members of the band played "Music Must Change" only a handful of times in 1981, before placing it into early retirement.

While certainly a grim reminder of the darkness surrounding Moon's final days, the song's curse goes even deeper. When The Who finally decided to resurrect "Music Must Change" for a 2002 tour, bassist John Entwistle died just one day before the band was scheduled to hit the road. It was enough for Daltrey to lay the song to rest forever. "I kind of got a weird feeling about it," he told Stern. "Because it [the song] is about how it's gotta move on...and that it's our time to move on."

If you or anyone you know needs help with addiction issues, help is available. Visit the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration website or contact SAMHSA's National Helpline at 1-800-662-HELP (4357).

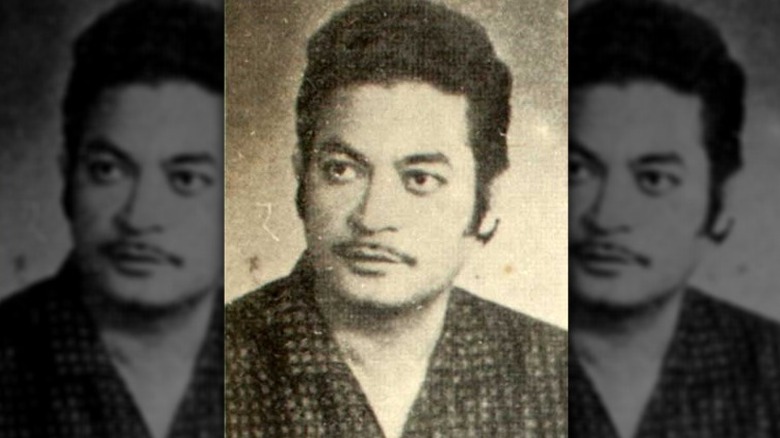

Insha Ji Utho – Amanat Ali Khan

As illustrated by the curious case of Pakistani singer Amanat Ali Khan's biggest song, some words just weren't meant to be sung. The lyrics of "Insha Ji Utho" – Hindi for "Get Up, Insha" — were originally a poem written by Pakistani author Ibne Insha in the 1970s. In it, Insha tells the story of a disenchanted man who decides on a whim to leave his city — and his lover — for good.

Inspired by the poem's dark take on urban life, Khan got Insha's permission to put it to music and make it into a ghazal, a type of classical song based on Arabic poetry. After he sang it on television in 1974, it became a huge hit. But, just months after its success, Khan died suddenly of appendicitis at age 52. Four years later — on the exact date of the song's release — Insha, the poet who penned its words, died of cancer.

One day before his own death, Insha attributed Khan's passing to the song. "Yeh manhoos ghazal kitno ki jaan ley gi?" he wrote to a friend (via Dawn), which translates to: "How many more lives will this cursed poem take?" The answer was at least three more. First, Khan's son, Amjad, died after singing it. Then the song's producer, Khalil Ahmed, died. Finally, another of Khan's sons, Asad, also died at age 52 not long after singing his father's famous ghazal at a 2006 concert — it was the last song he ever sang.

Devil's Trill Sonata – Giuseppe Tartini

Some songs are cursed from their inception, as was the case when Italian composer Giuseppe Tartini received inspiration for his famous "Devil's Trill Sonata" from an especially creepy dream he had in 1713. Tartini maintained that he didn't write the sonata — the devil did when he schooled him on violin as he slept. "How great was my astonishment to hear him play, with such consummate art and intelligence, a sonata more exquisitely beautiful than anything I had conceived in my boldest flights of fancy," Tartini said of the devil's violin skills in French astronomer Joseph Jérôme Lalande's 1769 Italian travelogue (via SF Symphony). "I felt enraptured, transported, spellbound."

Once awake, Tartini tried — and in his view failed – to reproduce the devil's flawless intensity. Still, the 15-minute four-movement song — with its demanding bow work, challenging string crossings, double stops, and trills that span three keys — is remarkably difficult for even skilled violinists to play. It's certainly not hard for anyone who has listened to or attempted to play it to believe in its alleged devilish origin.

While the song doesn't curse those who play it — unless you count all the blisters and frustration — its spooky creation story made an indelible mark on pop culture, even featuring in the 2020 piano horror movie "Nocturne." After all, playing the violin with the devil is typically synonymous with selling one's soul in folklore – we all know the reason the devil went down to Georgia.

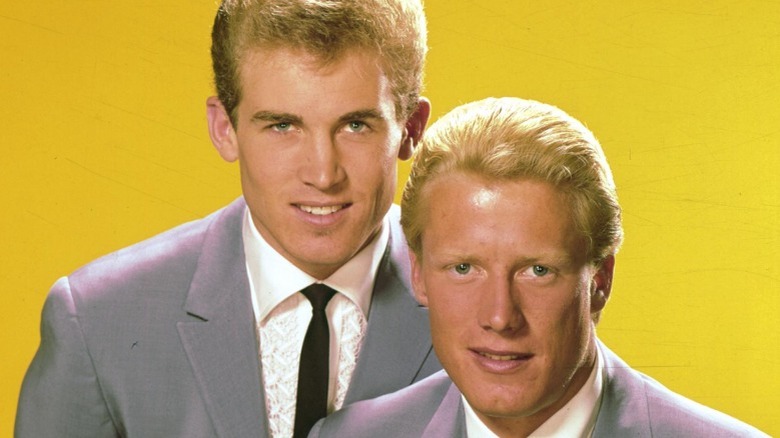

Dead Man's Curve – Jan & Dean

California surf rock duo Jan & Dean – best known for their hits "Surf City" and "The Little Old Lady from Pasadena" — were a big deal in the 1960s, when The Beach Boys dominated the airwaves and cruising in brightly colored hot rod cars was all the rage. But one of their most popular songs, 1964's "Dead Man's Curve," ended up being eerily prophetic.

In the song, the duo sings of racing in a Chevrolet Corvette Stingray on a winding section of a Los Angeles road called Dead Man's Curve, somewhere near Sunset Boulevard and Vine Street. As you might expect, it doesn't end well. "Well, the last thing I remember, Doc, I started to swerve," the duo sings in the song's last verse. "And then I saw the Jag slide into the curve; I know I'll never forget that horrible sight. I guess I found out that everyone was right; won't come back from Dead Man's Curve."

Two years later, life imitated art: On April 12, 1966, Jan Berry — the group's primary songwriter — crashed his own Stingray while driving too fast on Sunset Boulevard. The horrific accident happened on Sunset Boulevard and Whittier Drive, just six miles away from the tune's setting. Unlike his created protagonist, Berry did come back from Dead Man's Curve. But he suffered lifelong severe brain damage, partial paralysis, and speech impairments. It also derailed his career at the peak of his popularity. Many wondered: Did the song curse him?

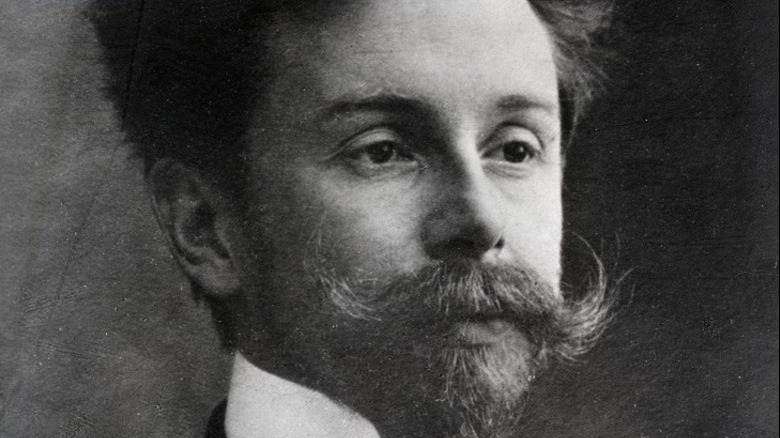

Piano Sonata No. 6 – Alexander Scriabin

Russian composer Alexander Scriabin was known for his innovative and progressive style and 10 successful piano sonatas. But, in 1911, he wrote a piece of piano music so intense he scared himself. According to Scriabin in Faubion Bowers' book, "Scriabin: A Biography," he described his sixth sonata with such unflattering words as "nightmarish," "unclean," and "mischievous." In fact, Scriabin was so afraid of his own creation that he never played it in public and, when he played it for friends, he appeared visibly frightened and sometimes physically trembled.

Scriabin's biographer, Bowers, logically attributed the song's darkness to its haunting minor thirds and unsettling perfect fourth and fifth harmonies. Still, in addition to describing the song as "satanic," he had this to say about it: "Its dark and evil aspect embrace horror, terror, and the omnipresent Unknown...Its mood directly inherits the inchoate, incomprehensible, unformed chaos of the dark beginning — the Void."

All of this certainly imbues the song with sinister supernatural undertones, suggesting Scriabin was merely a conduit for the malevolent forces that brought its notes into the world. It's certainly not the wildest theory — some believed Scriabin's sixth sonata predicted the coming of The Great War in Europe. On April 27, 1915, after composing four more pieces — including the equally terrifying ninth sonata that became known as "The Black Mass" — Scriabin died of septicemia caused by a mysterious sore on his lip at the height of his career. He was just 43 years old.