Numerology In Egyptian Myth Explained (And Why 3 Is So Important)

Ancient Egyptians loved their numbers. Sure, if you take stock of their many centuries of mythology, you may be dazzled by all of the animal-headed gods and arcane directions for getting to a plum spot in the afterlife, but there's more to it all. A closer look reveals that, over nearly 3,000 years of engaging with religious belief, the people of ancient Egypt put a lot of mystical weight behind certain numbers. Soon enough, you'll be noticing key numerals, like three, four, and seven, just about everywhere in the region's mythology.

Ancient Egyptians had a pretty sophisticated understanding of mathematics. They would have to, if they wanted to keep track of the pharaoh's reign, tax everyone, and make sure that the pyramids and other monumental architecture wouldn't just slump into the ground as soon as workers were finished. Even if someone wasn't a scribe trained in writing out the sometimes admittedly clunky series of hieroglyphic figures, numbers still played a large role in their lives.

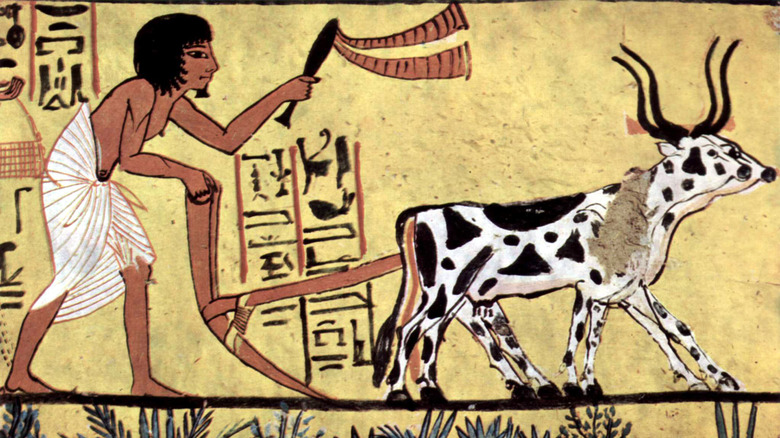

Even the humblest farmer needed to understand the divine turning of the three seasons, for instance. And any worshiper, whether at temple or home, would do well to remember just why the divine trio they were addressing came in a group of three. What's more, in a world where spells were a serious part of caring for the sick, paying attention to magical numbers like seven could mean the difference between life and death. Here's numerology in ancient Egyptian myth explained.

Duality was a key concept in ancient Egypt

Often referred to as ma'at, the notion of harmony underpinned the cosmos, in which the forces of order balanced chaos. Given that ma'at was around since nearly the beginning of creation, this duality was fundamental to all existence.

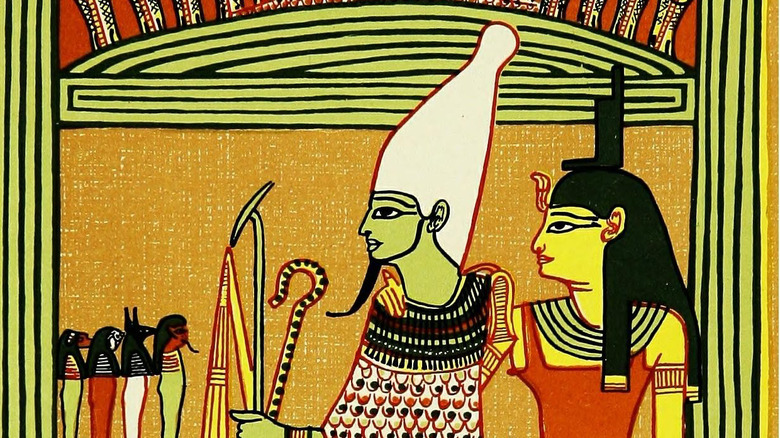

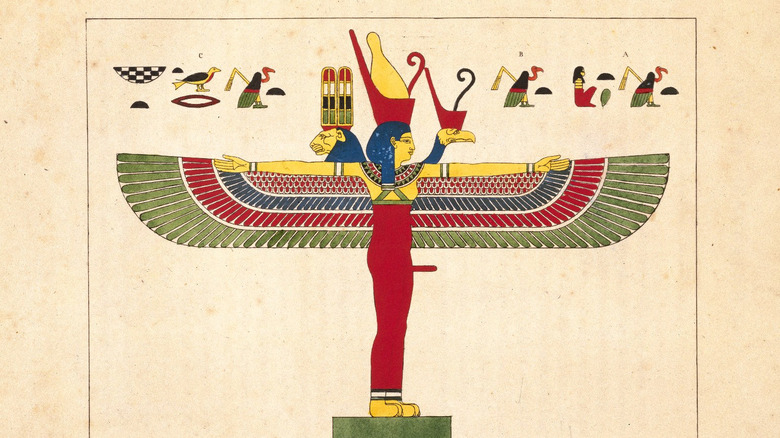

Often, duality was complimentary, where one part of the pair couldn't exist without the other. What was the sky without the earth, or the day with no night? In art, the gods often showed up with a divine companion, such as when the underworld deity Osiris was depicted with his wife, Isis. She balanced Osiris by connecting to the world of the living through her associations with women and the power of magic, and even as an arbiter of fate. The roles of Isis and Osiris were reflected in Egyptian society, where women and men were believed to inhabit complementary gender roles that embodied the duality of the greater cosmos.

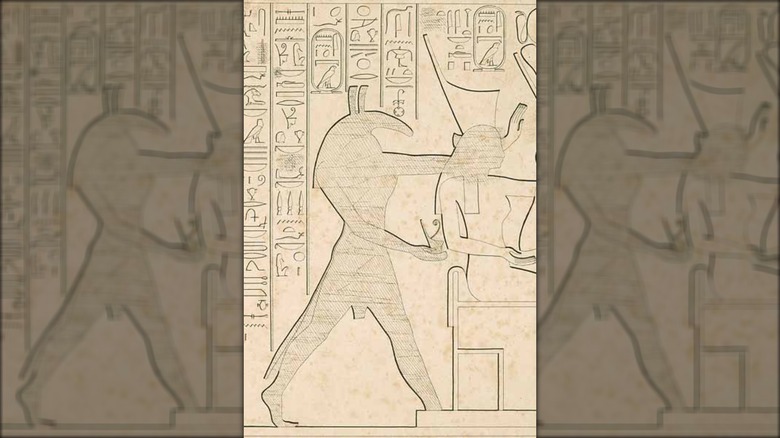

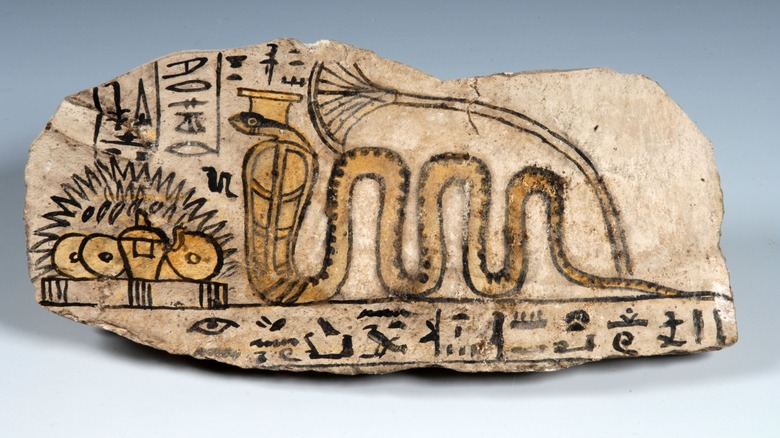

Duality could be more dramatic, however. One myth held that the sun god, often in the form of the falcon-headed Re, had to undertake a perilous journey through the underworld (known as duat) every night. While humanity slept, he and other order-loving deities had to sail through an encounter with a giant serpent. Known as Apophis, the monstrous snake represented the dangerous chaos that could overtake existence if the gods ever wavered. Even puny humans were expected to do their bit, undertaking rituals meant to shore up the forces of Re and defeat Apophis.

Some trace the idea of a holy trinity back to ancient Egypt

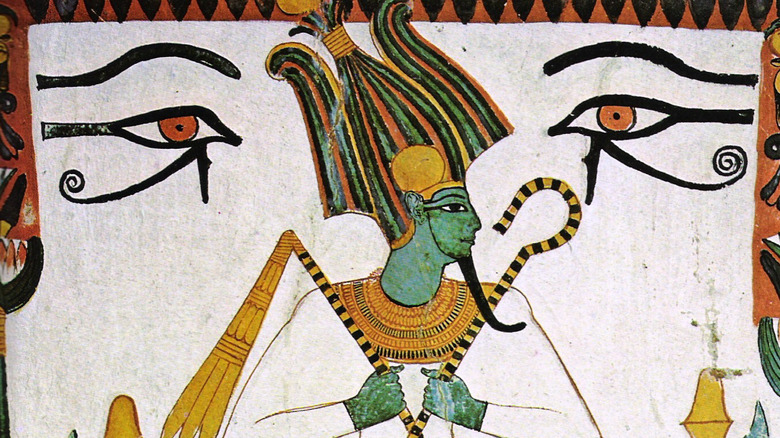

Ancient Egyptians were especially interested in the concept of three gods appearing at a time, often depicting divine groups of three in art and literature. Other gods might represent three aspects of a whole, such as Re, Khepri, and Atum as the sun. Amun, Re, and Ptah were also sometimes interpreted as different aspects of a single sun god.

If all of this is starting to sound familiar to anyone with at least a passing knowledge of Christian theology, things get even more parallel when it comes to family-based triads. Perhaps the most famous in ancient Egyptian mythology is the mother-father-son group of Isis, Osiris, and Horus. However, plenty of other godly family groups made their mark, like Ptah, Sekhmet, and Nefertum or Amun, Mut, and Khonsu. Sometimes, the triad consists of a male god and two female deities, or a female and male set with their divine child, but a familial connection was often present.

As Jennifer Williams writes in the Journal of Black Studies, early Christians in the ancient Mediterranean world came across preexisting models of holy families and three-deity groups from Egypt and other regions. From there, it would have been only a short intellectual jump to incorporate that model into things like the Holy Trinity or the Holy Family of Jesus, Mary, and Joseph — only, with a significantly depowered version of Isis in the form of the Virgin Mary.

Ancient Egyptians connected three to natural cycles

Three's importance in Egyptian mythology may connect to the natural environment experienced by the people of this ancient world. In a society that depended so much on agriculture, the cyclical flooding and retreat of the Nile, which deposited rich mud onto farmlands, was vital. The year that helped to give shape to this process was split into three seasons closely linked to the movement of the great river: Inundation (Akhet), Emergence (Peret), and Harvest (Shemu). These were then subdivided into 30-day months reckoned as three 10-day groupings (though, by the Old Kingdom period about 4,000 years ago, calendar-makers were reckoning in five extra days to keep the year more or less balanced).

The ancient Egyptians also linked the number three to the sun and the god (or gods) that kept it moving through the sky. In the morning, the sun deity was the beetle-headed Khepri, turning into Re at noon, and Atum as the day wound down. The three might be depicted all together, as a scarab, a solar disk, and a ram. This structure was reflected in the cycle of religious observances, which priests often undertook three times a day as part of their temple duties. And during the New Kingdom period, the concept of time was connected to a divine trio. In a text of the Book of the Dead from that time, the undead Osiris was connected to yesterday, the falcon-headed Horus to the current day, and Ra to tomorrow.

Three could also spell strife and instability

While the number three is often seen as a highly stable thing in the context of ancient Egyptian mythology, things aren't always so harmonious. In fact, some trios are full of operatic levels of strife, perhaps indicating that three was a crowd even thousands of years ago.

One of the most retold and important myths from ancient Egypt concerns the siblings Isis, Osiris, and Set. Osiris was a big deal, teaching humanity not just how to farm, but also to live in a civilized society. He was beloved by Isis, a goddess with a wide purview that included fertility, birth, rebirth, and death. Set (also sometimes referred to as Seth), grew envious of his brother and so killed and dismembered Osiris, tossing the parts all over Egypt. Isis was able to reassemble and briefly revived her husband long enough to conceive a son, Horus. But it didn't take, and Osiris was forced to enter the underworld and rule over the dead.

With Osiris more or less out of commission in the world of the living, another fraught triad arose. A pregnant Isis hid from Set in the thick vegetation along the Nile. After she gave birth to Horus, the younger god grew to defeat his treacherous uncle. Finally, Horus was able to restore balance to existence by containing the chaotic, destructive force represented by Set.

Four could represent completeness

Four was a pretty powerful number in ancient Egypt, if its frequency is any indication. There are the four quarters of the heavens, supported by four pillars and controlled by four rudders. The entire cosmos was sometimes divided into quarters: the sky, heavens, earth, and the underworld. Moreover, there were four cardinal directions often referenced in rituals. Even the human species was sometimes divided into four categories (Asiatic, Nubian, Libyan, and Egyptian people).

One especially notable example is on display in almost any museum's Egyptian exhibits, assuming you know where to look. These would be four canopic jars, stone containers meant to house the preserved organs of a mummified individual. Safely tucked away in someone's tomb, the four jars were decorated with the heads of the Four Sons of Horus. Each was set to guard over a particular organ. The baboon-headed Hapy watched over the lungs, the human Imsety over the liver, the jackal Duamutef over the stomach, and the falcon-headed Qebehsenuef over the deceased intestines. Some funeral shrines, like the canopic shrine of the famous young king Tutankhamun, could also have four goddesses standing guard, each at a side or corner with arms outspread to cover the deceased.

But why was four so satisfying? It may have reflected a sense of completeness that would have been deeply satisfying to harmony-focused Egyptians. After all, if a number can reference practically all of existence, as four does with the cardinal points, it's got to be pretty solid.

Egyptian myth gives seven a connection with magic

Magic was a pretty big deal in the ancient Egyptian world. It allowed humanity to draw on the divine forces that underpinned their existence, helping to bring justice and balance to their lives. If someone grew ill, a doctor-magician might be called to help, bringing along texts that included both practical medical advice and powerful spells. If another person was preparing to go through the dangerous event of childbirth, they would use magic to ease the way, perhaps appealing to the dwarf god Bes to protect them. Even after death, people were often buried with magical spells inscribed on tomb walls, written on papyrus, and painted on their sarcophagi to ensure they made it to the afterlife.

For ancient magicians practicing their art in Egypt, one figure, in particular, might have popped up often: the number seven. Along with spells, embalmers might anoint the dead with seven oils, or a doctor could use a series of seven knots to ease one of a number of ailments.

Then there's Neith, already considered to be an ancient goddess many centuries ago. This powerful figure reigned over matters involving creation, death, and war. Some accounts of creation even give her credit for birthing Atum, who then proceeded to create the rest of existence. She reportedly gave rise to this order by engaging in a deep and powerful sort of magic that involved speaking seven words.

Ancient Egyptian gods might come in seven forms

Seven also proved to be an important number when gods started to show up. The popular Hathor, the goddess of such crowd-pleasing things like fertility, love, music, and dancing, sometimes appeared in sevenfold form as a group of cows. Rather prosaically, mystical texts like the Book of the Dead often refer to them as the Seven Hathors. However, their individual names are more striking, with epithets like "Storm in the Sky," "She whose name has power," and the "Silent One." Together, they often functioned as the pronouncer of an individual's fate after the person was born.

Hathor wasn't the only Egyptian deity to appear seven times over. The sun god Re was often said to have seven different bas — effectively, different forms of the soul, with the ba in particular often shown as a bird with a human head. Ma'at, as a feminine deity representative of the larger concept of divine order, was also sometimes referenced as having seven forms.

Even unique deities might come around in groups of seven like the main lineup often worshiped at the site of Abydos. That particular group included Ptah, Re-Horakhty, Amun-Re, Osiris, Isis, Horus, and the deified pharaoh Seti I (whose memorial temple housed a grand boat shrine dedicated to each deity). Eventually, Osiris stood out as the leader of this ancient band, drawing many pilgrims to the area.

Seven is connected to the Egyptian afterlife

Osiris, the great lord and judge of the underworld, carries plenty of associations with the number seven and its multiples. In the temples of Abydos, a city that eventually became dedicated to his worship, figures of Osiris were ritualistically embalmed and then held for seven days before the next step in the process.

In the version of the Osiris myth related by the ancient Greek philosopher Plutarch, the corpse of Osiris is dismembered into 14 different parts by his jealous brother, Set. Other accounts claim that the undead god was split into 42 different parts — a multiple of seven. However, other versions, like the one by Greek historian Diodorus Siculus, claim it to be 16 pieces.

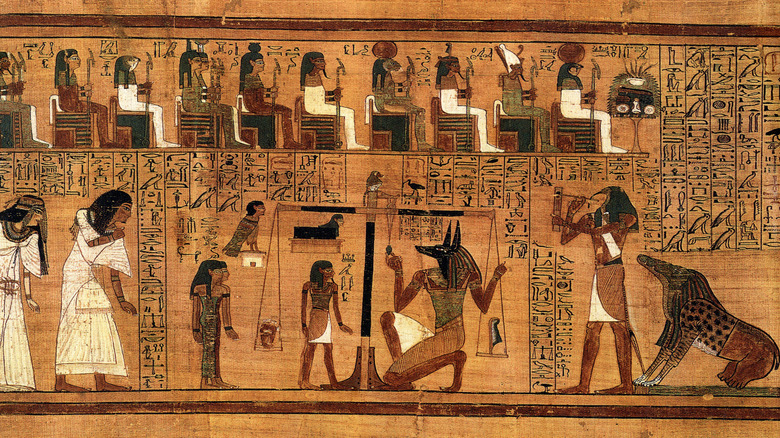

For deceased ancient Egyptians carefully consulting their edition of the Book of the Dead for the right path to paradise, it was smart to keep an eye out for the 21 gates between them and the afterlife. Hopefully, they were also aware that the number of judges who would be deciding the fate of their soul often came out to a whopping 42 deities. However, Egyptian artists weren't always ready to painstakingly depict all 21 gates or a panel of 42 divine judges, especially if they were working on a small scale on something like a papyrus scroll. Instead, they might revert to a more comfortable seven that viewers would understand represented the larger number.

Dead souls needed to pay attention to numbers

Getting to the ancient Egyptian afterlife took serious work. But, while things like food offerings and servant figures known as shabti were meant to keep the dead well-supplied, instructions were likely the most important thing of all. From the Pyramid Texts inscribed into the stone walls of elite Old Kingdom tombs to text painted on less fancy coffins, the dead were often supplied with a manual meant to guide them into the afterlife. Those directives often hinged on important numbers.

According to some accounts inscribed on the walls of high-end tombs, the underworld contained 12 gates that the sun god had to clear on his nighttime journey through the land of the dead. Each is guarded by deities, often appearing in sets of significant numbers like seven, 12, and two. Other texts maintain that the dead will only have to pass through seven gates, though the obstacles spirits faced must have made living ancient people shudder, as gods with terrifying names like "Upside down of face" and "Existing on Maggots" waited with knives. If the deceased greeted them properly, they were allowed to pass without harm. Other dead folks had texts that claimed they would need to navigate a dizzying 21 portals, however. The fact that it is a multiple of the magic number seven would probably have been of little comfort to the forgetful Egyptian (hopefully, the dead were allowed to bring their notes to the test).

One ancient Egyptian story relies on number symbolism

One Egyptian story, popularly known as the Tale of the Doomed Prince, is partially preserved on a papyrus dating from the 18th Dynasty, over 3,000 years ago. It's got plenty of drama but, for readers with close attention to detail, plenty of revealing information about the Egyptian love of mystical numerology.

A 1907 English translation of the legend starts with a king who longs for a son. After petitioning the gods, his wish is granted, but there's a catch. The Seven Hathors appear and say the boy is doomed to die. They claim that the prince will meet his end facing one of three animals: a crocodile, dog, or snake.

The king tries to protect his son but eventually allows the boy to have a hunting dog and then travel out into the world. The young man then wins the affection of a princess in a tower, marries her, and brings her back to Egypt. Yet the three animals keep crossing his path, from his beloved canine companion to a snake killed by the princess, and even a crocodile that speaks of its desire to cause the prince's tragic death. In an agonizing turn, this is where the only copy of this tale cuts off, its papyrus crumbling into nothing. Does the prince escape his fate? How does the deadly trio resolve itself? Does magic get involved? Motivated fiction writers might fill in the blanks, but everyone else has been left hanging.

[Featured image by Museo Egizio via Wikimedia Commons | Cropped and scaled | CC BY 2.0 IT]