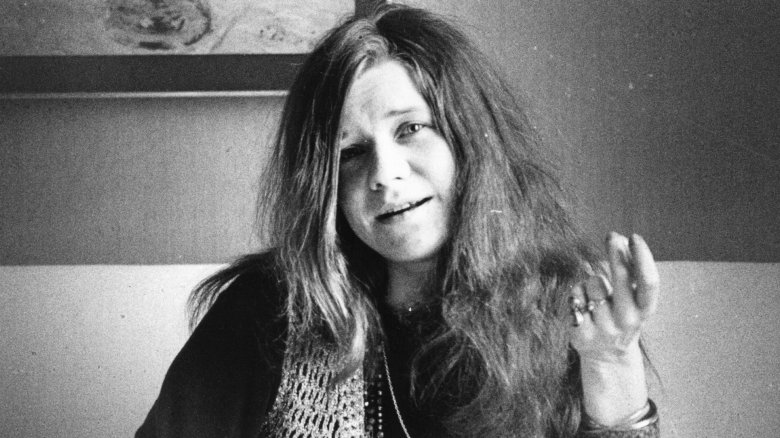

Janis Joplin's Tragic Real-Life Story

Almost half a century since her death from an accidental heroin overdose, Janis Joplin's legacy as an icon of psychedelic rock and blues remains nothing less than momentous. Known affectionately to her fans as Pearl, Joplin rose to prominence on the San Francisco music scene during the 1960s, performing both with bands and as a solo artist. She cemented her legacy with appearances at the historic Monterey Pop and Woodstock festivals and garnered a reputation for her hypnotic, deeply charismatic on-stage persona.

In 1970, however, Janis Joplin's life came to a swift and tragic end. Her death was the punctuation mark to a short life of excess, addiction, and illness, spurred on by memories of an uneasy childhood and the troubles of an uneven existence. From the home that couldn't understand her to the men who betrayed her to the music that gave her purpose, this is the tragic, brilliant life of the Pearl of San Francisco.

Port Arthur blues

Janis Joplin was born in Port Arthur, a small city in Texas' Jefferson County, in 1943. Her mother was a college registrar and her father was a Texaco engineer. The young Joplin quickly developed a love for blues music, which only served to alienate her from the very white, wealthy community in which she lived. To say the middle-class citizens of the American Deep South were not fans of blues music — a genre then associated with African-Americans — is an understatement, to say the least.

Nowhere is this clearer than in Port Arthur's refusal to embrace Joplin's legacy. In fact, it wasn't until 18 years after she died that Port Arthur recognized its connection to the singer. Things weren't exactly helped along by the fact that Joplin had died of a drug overdose. Nowadays, however, Port Arthur celebrates Joplin's life with billboards, brochures, and even an annual concert in her honor.

Her merciless peers

Although she eventually earned a reputation for outspokenness, charisma, and an easy-going charm, Janis Joplin's childhood encouraged anything but. During her youth and adolescence, she was bullied relentlessly. She was overweight for her age and afflicted by acne, and her peers never let her forget it, calling her "pig" and "whore" and mockingly throwing pennies at her. According to Joplin, "They laughed me out of class, out of town, out of the state."

In 1970, only weeks before her death, Joplin showed up to her high school's reunion in Port Arthur (adorned in feather boas and accompanied by the media) "just to jam it up their asses," to "see all those kids who are still working in gas stations and driving dry cleaning trucks while I'm making $50,000 a night." After she died, her will stipulated specifically that she was not to be buried in Port Arthur. That jab — as well as her ruthlessness toward the town in the national press — did nothing to endear the residents of Port Arthur to their most famous daughter. Joplin, for what it was worth, never seemed to care.

San Francisco takes a heavy toll

Janis Joplin left Texas as soon as she could. In 1963, she moved to the city's Haight-Ashbury district — an area recognized today as being the cradle of hippie culture. It was here that she began her career as a musician, taking up occasional work as a folk singer. It was also in San Francisco that Joplin began to embrace the drug culture. Before long, she had become known as a speed freak. Coupled with her penchant for Southern Comfort whiskey and a predilection for heroin, Joplin's lifestyle during her first stint in San Francisco did nothing for her health or her state of mind.

Her weight bottomed out at 88 pounds. Her friends began to worry about her "skeletal" appearance, and eventually organized a bus fare party to raise the funds to send her back home. Finally, in 1965, Joplin returned to Port Arthur.

Going straight

Not yet a rock star, Janis Joplin's homecoming at Port Arthur was, according to her sister Laura Joplin, "the beginning of a very positive period in her life." She quit drugs and gave up alcohol, and even famously changed her hairstyle to the beehive, a popular do at the time. She re-enrolled at Lamar University (above), where she studied anthropology. But she never gave up the music: Joplin would travel to Austin on occasion to perform at bars and in local shops. Life on the straight and narrow, however, didn't last very long.

Eventually, she returned to drugs and alcohol. She gained her weight back, too, which compelled a new bout of abuse from her peers at college — members of a frat house on campus dubbed her the "ugliest man on campus" and had the school paper report on it. Joplin, meanwhile, found an escape of sorts in music. She threw herself into her songwriting and slowly but surely began to hone and refine the sound of her voice.

A brush with normality

Janis Joplin had met Peter de Blanc during her time in San Francisco. Their relationship, according to Laura Joplin, was "intense," on account of his drug addiction being even worse than hers. Now, though, Joplin lived in Port Arthur while de Blanc lived in New York, working for IBM. During one of his visits to Texas, de Blanc asked Joplin's father for permission to propose to her and, soon after, the two were due to be wed. Joplin and her mother began to plan the wedding, but only a few months later, Peter called it all off. He had gotten another woman pregnant and was planning to marry her instead.

In a letter sent to de Blanc in the midst of their relationship, Joplin had written: "I really love you. In attempting to find a semblance of a pattern in my life, I find I've gone out with great vigor every time and gotten really f****d up. All I did was be wild, drink constantly, ... sing. Jesus ... Christ, I want to be happy so ... bad."

Finding her sound

In 1966, an old friend of Janis Joplin's from San Francisco tracked her down and invited her to front a blues band he was managing at the time. Joplin, jilted by her ex-lover and thoroughly done with the bullying she'd endured at college, didn't struggle to make the decision. She returned to a San Francisco in the throes of hippie culture — psychedelia reigned supreme, rock music was everywhere, and the bohemian life seemed like the only life worth living. The band she joined was known as Big Brother and the Holding Company.

Despite finding little success with their early singles, Big Brother eventually found their break at the legendary Monterey Pop Festival. Joplin's vocal performance during the band's cover of Big Mama Thornton's "Ball and Chain" has since gone down in rock myth. Big Brother — and, in particular, Joplin herself — had finally begun to make waves, and their popularity would only continue to grow.

At the whims of cheap thrills

Big Brother and the Holding Company (pictured above) released their second and most successful album, Cheap Thrills, in 1968. Described by Clash as "a record of near-perfect intensity," Cheap Thrills was a raw, passionate testament to the strength of Janis Joplin's voice and the talent of Big Brother's other members. At time of release, it was — thanks to the efforts of other psych-rock acts like Jefferson Airplane and Country Joe and the Fish — one of the most hotly anticipated releases of the year. Naturally, this did wonders for the album's figures: Cheap Thrills would top the Billboard charts for eight weeks and sell over 2 million copies. It also made Joplin herself one of the most recognizable music faces of the decade.

By this time, however, Joplin had begun to outgrow Big Brother. Only a few months after Cheap Thrills' release, she left the band to pursue her own solo career.

Drink, dope and Kozmic Blues

Janis Joplin next formed the Kozmic Blues Band, the group that would back her while she embarked on a solo career. Unfortunately, however, the band's music met with only a lukewarm commercial reception: Their first album, despite being critically acclaimed, failed to match the chart successes of Big Brother and Cheap Thrills. Worse still, Joplin's decline into addiction was proving more and more troublesome by the day.

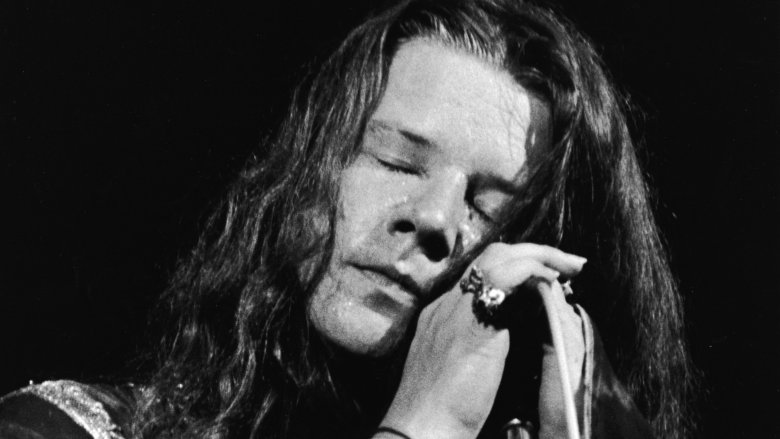

Around 1969, she was said to be using around $200 worth of heroin every day, which doesn't leave a lot of room for keeping yourself together. This heavy drug use and near-constant drinking began to impact her live performances. During a headline slot at Woodstock she admitted to being "three sheets to the wind," and that same year she went on stage at Madison Square Garden so drunk, stoned, and out of control that one biographer said "she could have been an institutionalized psychotic rent by mania." At the end of 1969, the Kozmic Blues Band broke up.

A pearl in the rough

Janis Joplin's second backing group was known as the Full Tilt Boogie Band. In 1970, she entered the studio and began recording the album which would eventually be released as Pearl. Under the guidance of Doors producer Paul Rothchild, Joplin and the Full Tilt Boogie Band recorded almost a dozen songs, including an a cappella version of her original song, "Mercedes Benz," which is today remembered as one of her greatest works.

Pearl is regarded by many as Joplin's finest hour. In 2012, it made No. 125 on Rolling Stone's list of the 500 best albums of all time. Pearl was praised in particular for its intimacy, its raw strength, and the focused sound she just couldn't quite find with the Kozmic Blues Band. It would chart at No. 1 on the Billboard charts for nine consecutive weeks and become a certified quadruple platinum record. Joplin would not survive to see it released.

Death in Hollywood

On October 4, 1970, Janis Joplin was due to arrive at the Sunset Sound Studios in Hollywood for further recording sessions on Pearl. She failed to show up. Rothschild sent Joplin's road manager, John Cooke, over to her hotel to find out where she was. Her car was parked in the lot and her drapes were drawn. When Cooke knocked on the door, there was no response. He fetched the manager and they broke into the room. They found Joplin dead on the floor, with bloody lips and a broken nose. A small amount of change — still unexplained to this day — was clutched in her fist.

Later reports confirmed she had died of a heroin overdose and suffered the other wounds when she collapsed. After a private funeral, she was cremated and her ashes scattered over the Pacific Ocean, just off Stinson Beach in California. At the time of her death, Janis Joplin was just 27 years old.