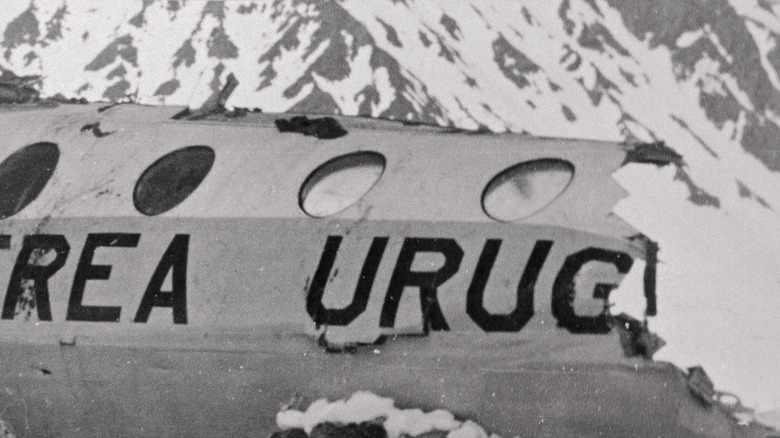

What Happened To Flight 571's Survivors After The Harrowing 1972 Crash?

We may receive a commission on purchases made from links.

If there's anything that's known about the ill-fated Flight 571, it's that those who survived the initial crash turned to cannibalism in order to survive. The reality is much more complex than that, and the heart of the tragic story is really about survival — and what perfectly ordinary people find themselves capable of in extraordinarily horrible circumstances. It's also about the greater good: When survivor Roberto Canessa spoke with National Geographic, he explained: "My mission was not to just think what was better for me, but what was better for the group."

A total of 16 people survived to be rescued, and that's in large part due to not only Canessa and Nando Parrado deciding to try to walk out of the Andes but because of the group's resourcefulness in repurposing part of the downed plane for warmth and shelter. "You get very smart when you are dying," Canessa explained. It's an eerie thought.

Multiple books have been written about those events high up in the Andes, including Canessa's "I Had to Survive: How a Plane Crash in the Andes Inspired My Calling to Save Lives." Canessa said that he encouraged all 16 survivors to write their own version of the story: "Because they are 16 different stories of survival. ... Who survived? It wasn't the smartest, most intelligent ones. The ones who survived were those who most felt the joy of living. That gave them a reason to survive." So ... what happened next?

Roberto Canessa

When National Geographic asked Roberto Canessa why he believed he was one of the handful of survivors, he simply said, "Because I was lucky." His survival would end up being key for the survival of others, too: As a medical student, he was able to treat injuries and infections, set broken bones, and — later — he was the one who sliced meat from the corpses of their friends.

Canessa carried on with his medical training and has since become one of the world's top pediatric cardiologists. He credits his experiences on the mountain for giving him the perspective needed to not only get through some of the most difficult cases and surgeries but to help parents get through them, too. He said: "When I see a baby in a mother's womb, with half of its heart missing, looking through the window of the ultrasound machine is like seeing the moon through the window of the plane that night. But now I can be the shepherd who can make this child survive." As for his own first-born child, Canessa named him Hilary — after the mountain they crashed on.

In his book, "I Had to Survive," Canessa wrote about how his newborn patients remind him of the life-or-death struggle they faced on the mountain. His experiences shaped him as an adult and as a doctor: "My ways are the ways of the mountains. Hard, implacable, steeled over the anvil of an unrelenting wilderness in which only one thing matters: the fight to stay alive."

Javier Methol

Javier Methol was the oldest survivor from the crash of Flight 571: He was 36 years old at the time and was one of the rugby team's coaches. Also on board was his wife, Liliana, who was killed in an avalanche that claimed the lives of seven other people as well. At the time of the crash, he and Liliana had four children, and he cited his children as his motivation to survive.

Before the crash, Methol was an executive with the family cigarette business, and he'd already seen his share of trauma, including losing a right eye after being hit by a car. After he and 15 others were rescued from the Andes mountaintops, he returned to the cigarette industry, became a sales and corporate affairs director, and made regular public appearances to talk about the flight, the crash, and how he had relied on his faith to see him through.

Menthol became the first of the crash survivors to die, passing away in 2016 about a month after being diagnosed with an aggressive form of cancer, and just a few months before what would have been his 80th birthday. He left behind his second wife and eight children from two marriages. When his passing was announced, fellow survivor Daniel Fernandez shared with EFE (via The San Diego Union-Tribune): "He was the best of all of us. He's the first to go and it's enormously sad. ... He was always helping others. A great guy. An example."

Fernando Nando Parrado

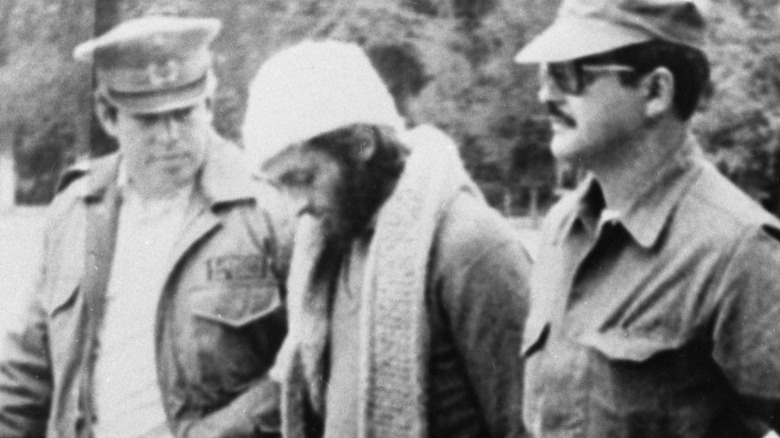

It was Fernando Parrado (center) who told Roberto Canessa that they needed to take the chance and try to hike out of the mountains, which they did. From the start, his survival had been accidental: He'd swapped seats with a friend who wanted to look out the window, and that friend died on impact.

On the 50th anniversary of the ordeal, he recalled to EuroNews: "In civilization, I might have broken down in a way that I wouldn't have been able to get up, but I didn't have time for that. ... I almost panicked, but I remembered that panic kills you, and fear saves you." Parrado had a lot to live for: In the years after he directed rescuers to his friends, he had a short stint as a professional race car driver, and has made countless appearances as a motivational speaker. He also co-wrote "Miracle in the Andes," and served as a consultant on "Alive," the movie based on the crash.

Parrado also took over the family business: His mother and sister died in that ill-fated crash, and he cited his father as one of the motivators that kept him putting one foot in front of the other in a bid to get home. He married, had two children, and penned this important life lesson: "I have learned that moments do not repeat themselves, but the next time I am dying I know that I will remember: my affections and love, not my businesses, cars, contracts, bank loans, earnings, emails, and airports."

Antonio Vizintin

When it came time to try to hike out of the mountains, Antonio Vizintin initially went with Fernando Parrado and Roberto Canessa, but when they realized just how far they were going to have to walk, Vizintin went back to help the two hikers conserve food. It was Vizintin, too, who was quoted first in Newsweek and then in The New York Times as explaining, "We never turned into animals, devouring another being or grabbed [sic] a piece of leg. We always did it with respect. In little bits."

Shortly after the rescue of the 16 survivors, The Washington Post reported that Vizintin had begun working at a real estate agency. The rescue, however, wasn't the end of tragedy in his young life: After returning to school for a law degree, he married, had two children, and found himself raising those children alone after the death of his wife.

He continued down the real estate development path, and like other survivors, has made countless public appearances to talk about their experiences on the mountain. He has since remarried, worked jobs in the packaging and food industries, and — according to his website — "lives a quiet, simple life."

Gustavo Zerbino

Perhaps even more surprising than their survival and rescue is what happened afterward for Gustavo Zerbino. He stuck with rugby, recruited players for a new team, and was back on the field 10 months after his rescue (and 88 pounds lighter than he was when he left on the ill-fated trip). Then, he led the team through a 14-year run where they took home 12 Uruguayan championships. He's also credited with raising the profile of the nation's rugby team, helping to make them an international contender, and with setting up a charity called Rugby Sin Fronteras, or Rugby Without Borders.

That's exactly what it sounds like: The organization sets up rugby matches between groups that are notoriously at odds, including games between Jewish and Palestinian children. The charity has gotten global recognition, and in 2015, Zerbino was invited to a meeting with the pope for his contributions to world peace through sport.

In addition to being the director and CEO of the Uruguayan Rugby Federation, he's also the CEO of his own pharmaceutical research company, and he's the head of another organization that oversees cooperation between different laboratories. When he sat down to talk to Chile Today, he explained: "In the mind, only two moments exist. The past, in which we feel guilt for the things which we cannot change, ... and the future, which is unknown, provoking angst and fear. ... The only place you can feel happiness and enjoyment is in the present."

Carlitos Paez

Carlitos Paez also wrote a memoir about his time stranded high up in the Andes, and his "After the Tenth Day" was lauded as a deeply personal look into not just what happened, but the impact that it had on him and — by extension — other survivors. It was Paez who shared an eerie insight with The Economic Times: "Eating human flesh doesn't taste like anything, really."

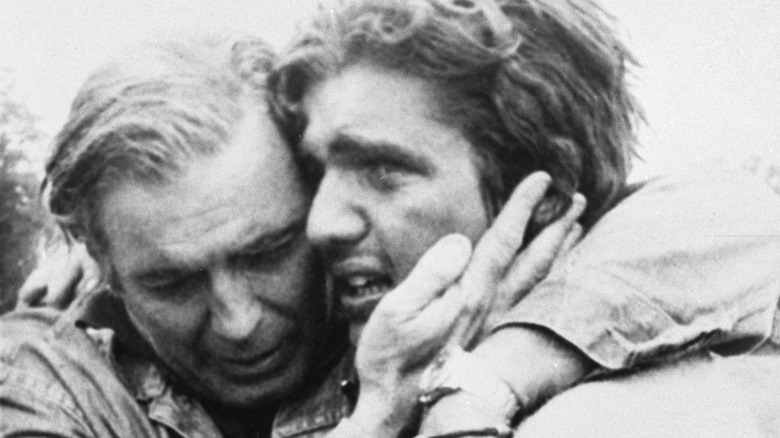

Since the rescue, Paez — pictured being reunited with his father — has become a motivational speaker who has done extensive traveling in order to share the story of those who lived and those who died on the mountain. He also got a degree in agricultural engineering, and later founded his own advertising and publicity agency. He's been incredibly outspoken and incredibly candid about what they went through — particularly when it comes to clarifying that no, they're not cannibals. "That bothered us, really, because it wasn't true," he said (via The Washington Post). "[A cannibal is] someone who kills another person because he likes to eat human flesh. We didn't do that." (The correct term is anthropophagy.)

Paez has also written two follow-up books: "My Second Mountain Range," and "From the Mountains of the Soul." In them, he details the lasting impacts the crash, rescue, and everything in between had on him, including his struggles with drug addiction.

Pedro Algorta

Not all the survivors were comfortable speaking or writing about the tragedy immediately: According to The Washington Post's 1978 look at what the survivors had been doing, Pedro Algorta had chosen to deal with the aftermath privately. The married father-of-two was working in a Buenos Aires bank and hadn't said much about what they'd gone through.

That changed in 2010 when Algorta flew to Chile. In the late summer and early autumn of that year, headlines were captivated by the story of a group of Chilean miners who were trapped underground after the collapse of a mine, and rescued a full 69 days later. Algorta spoke to Channel 4 about their rescue and his flight to Chile, saying that he knew exactly what they were going through, and that he had decided it was time to break his silence in order to reassure the miners and their families that life would go on.

"In my case, for 35 years, I didn't talk about it publicly. I just kept it for me, and it was a private issue. ... Then, at a moment in time, I thought ... I could do some good for others if I talked about it. ... We just received a beautiful reception ... we felt very close to the families who were going through the same situation as our families were experiencing 38 years ago." Algorta went on to release a book in 2016, called "Into The Mountains: The Extraordinary True Story of Survival in the Andes and Its Aftermath."

Eduardo and Adolfo Strauch

Eduardo and Adolfo Strauch are cousins, the only related survivors of Flight 571. In 2012, three survivors spoke to ITV around the 40th anniversary of the crash and rescue, including Adolfo. After the rescue, he had gone on to get into agricultural administration, telling the outlet that he helped some of Uruguay's farmers adapt to a changing world. He said that although he had been involved in the making of a new documentary, "Even now, I don't fully understand why people are interested in this particular story." He added: "I am thankful that we made this film because it makes history a little more objective."

In the years leading up to the crash, Eduardo had opened an architect's studio, and after his rescue, he continued to work as an architect and artist. He wrote the book "Out of the Silence" based on his experiences, and has since returned to the crash site as part of an Andes Survivors Expedition. When he spoke with NPR around the 2019 release of his book, he said it took him years to adjust to daily life again, adding that at the end of the day, he's grateful to be able to share their story because of the lives he's seen change.

"We have many cases of people who — they decided to commit suicide. And when they crossed with our story, it changed their thoughts. And they continue living. ... 47 years later, [it] became something so positive for me and for so many people."

Jose Luis 'Coche' Inciarte

Jose Luis 'Coche' Inciarte released his book in 2020. Called "Memories of the Andes," he shared that one of the first memories he associated with the crash was one of the most heartbreaking: Also on the flight was his best friend, Gaston Costemalle. He was originally intending on sitting with his buddy but was forced to sit elsewhere when he found the seat already taken. Costemalle was one of the first to die, falling from the plane as it broke into pieces.

After they were rescued, Inciarte returned home. His family owned a dairy farm, and it was there that he found his meaning — with the woman he had been engaged to before he took that fateful flight. He married his fiancée, Soledad, less than a year after returning, and went on to have three children. He told News 9 that when he returned, starting that family was a priority: "I thought so many times on that mountain I would never have one," he explained.

Inciarte has also done public speaking engagements to talk about the crash, and in 2011, he and fellow survivor Gustavo Zerbino spoke at the University of Manitoba. Among the thoughts and wisdom he shared was what he considered his most important message: (via ChrisD.ca) "Even if your legs are giving out, you are starving, and you don't think you could take another step, there is always more ... always."

Some of the survivors valued their privacy

When The Washington Post followed up with survivors way back in 1978, they found that while some found healing in the process of sharing their story, others were much more private in their search for normalcy.

Pancho Delgado had married, and settled down in Uruguay with his wife and two children, and became a notary public. When he played in the rugby match put on in honor of the 40th anniversary of the crash, he was the first to score. Daniel Fernandez also married and also settled in Montevideo, where he taught agriculture, while Bobby Francois and Alvaro Mangino became cattle ranchers. Roy Harley, meanwhile, returned to school for civil engineering.

Ramon Sabella also got into his family's business and stepped up to the head of a fruit exporter. He spoke with the German media in 2022 (via Zeit), recalling the moment they heard on the radio that the search had been called off. "We couldn't understand how our family and the government could abandon us," he recalled. When he got home, he learned he hadn't been forgotten about at all: His place at the dinner table was set for him every night he was gone.

Reunions happen on a regular basis

It's impossible to go through something like the crash of Flight 571 and the weeks stranded in the Andes without forming unbreakable, lifelong bonds, and according to Robert Canessa, that's exactly what happened. Not only do all of the survivors do their best to make it to an annual reunion celebrating the day of their rescue, but they also include the friends and families of those who died, in a celebration of their lives, too.

Canessa explained to National Geographic that many of the families remained close: "My children went to school with the nieces and nephews of those that died, and I think this was a very good healing process. ... It was something we endured, and had to live through." Canessa kick-started that: Not long after his rescue, he visited the families of each one of the people killed on the flight. "I felt it was my duty to tell them what happened," he said. "They didn't care about using the bodies of their sons for food. They cared about life."

In 2012, the survivors gathered on the 40th anniversary of their rescue, to play a commemorative rugby game in remembrance of the one that never happened decades prior. Among those in attendance was Sergio Catalan, who rode nearly 75 miles to summon help after seeing Roberto Canessa and Fernando Parrado across a river, and reading Parrado's note appealing for help. Catalan passed away in 2020, at 91 years old.