The Truth About King Tut's Curse And Its Victims

When Howard Carter opened the tomb of King Tutankhamun in 1922, as per History, the world went a little bonkers. What could be more intriguing than a bunch of rooms full of glittering treasure, buried under the sands of the Valley of the Kings for more than 3,000 years?

A mummy's curse, that's what. Why settle for boring golden masks, treasure, and creepily preserved corpses when you can also have death and despair, dogs howling at the exact moment of someone's death, and cobras enacting revenge upon little yellow birds? And so the curse of King Tut became a thing, the media ran with it, the public ate it up, and a century later there are still plenty of people who still believe it.

There's some room for skepticism, though, even though skepticism doesn't tend to be as much fun as death and despair. As it turns out, there aren't really many reasons to believe in King Tut's curse, other than the obvious one, which is the fact that curses are way more entertaining than non-curses, and also the continued employment of Hollywood special effects artists. So read this, and then feel free to keep on believing in the mummy's curse anyway. No judgment.

The ancient Egyptians had no concept of a cursed tomb

A lot of people assume the mummy's curse is part of ancient Egyptian mythology, meant to deter grave robbers from stealing the king's treasures. And while it is true that ancient tombs were designed to confuse potential thieves, in King Tutankhamun's time there was no concept of a written "curse," per se. That might have something to do with the fact that only about 1% of the Egyptian population could read hieroglyphics, notes Ancient Origins, and it's pretty unlikely that anyone that educated would be robbing tombs.

On the other hand, tomb builders could have spread the curse by word of mouth, but there's no evidence they did. According to National Geographic, the late Egyptologist Dominic Montserrat concluded there was "no ancient Egyptian origin of the mummy's curse concept." Instead, Montserrat said a 19th-century London stage performance, which featured the on-stage unwrapping of real Egyptian mummies, was the inspiration for the original stories.

Dig back deep enough into Egyptian history, though, and there does seem to be a tomb or two that promised divine retribution for grave robbers. Early mastaba-type tombs (which predate King Tut by 15 dynasties) sometimes included curse-like threats of death by wild animals, so perhaps these inscriptions persisted in the verbal mythology of ancient Egypt. Still, it really didn't seem to work very well as a deterrent, since tombs were usually completely picked over and looted by the time modern people discovered them.

The mummy's sort of sometimes curse

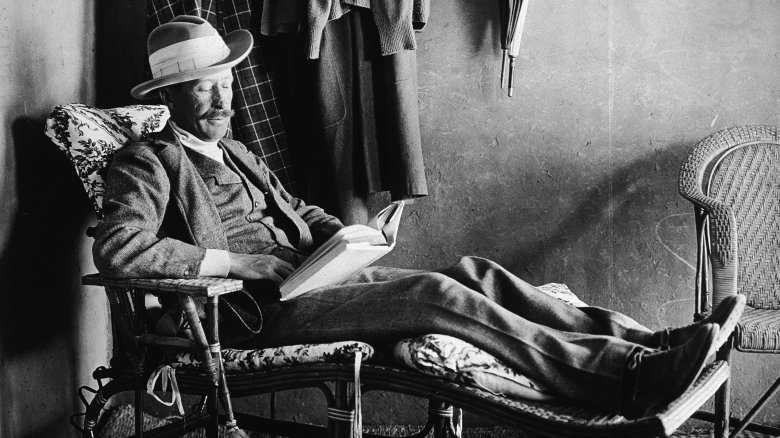

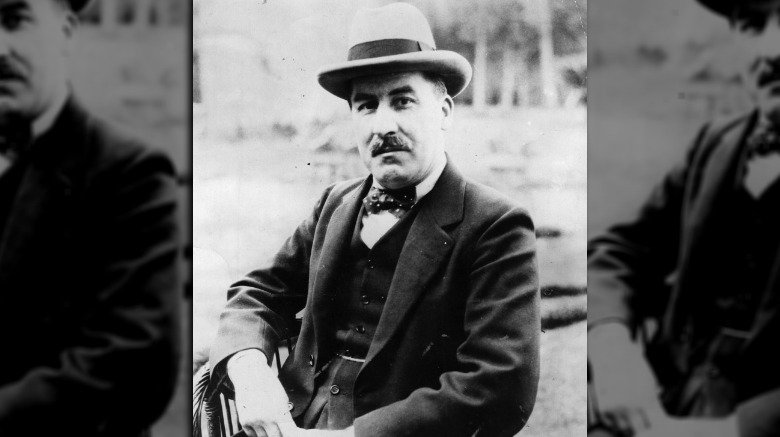

Depending on who you ask, there were 11 so-called victims of King Tut's curse, but most of the deaths really weren't that mysterious, with the exception of Lord Carnarvon, the first and most famous.

According to the Smithsonian, Carnarvon, the wealthy financier of Howard Carter's expedition, was bit by a mosquito then cut himself while shaving over the raised bite. That's really not something you would expect to kill someone, so the fact that it did kill him is part of what really gave momentum to the idea of a curse. The bite became infected, and Carnarvon died from blood poisoning. The timing was pretty ominous, too — his death occurred just two months after King Tut's tomb was opened, as per the Independent.

Carnarvon was already in poor health, though, and had been for more than 20 years, so on a logical level it's really not surprising that he was so susceptible to developing an infection. But his death wasn't the only one linked to the tomb — of the 58 people who were present for the sarcophagus' opening, 50 were still alive after 12 years.

So let's get this straight — other than Carnarvon, the curse could take up to 10 years to take effect, and it only struck down a handful of the people who deserved it? Maybe it's the sort of curse that loses its effectiveness over time, like a bottle of Viagra.

Canary in a cobra

We should not lose sight of the fact that there was some pretty seriously creepy stuff that went down after the tomb was opened. According to Time, when the archaeologists broke through to the first room they found two statues of Tutankhamun. The statues were life-sized, and on each head was a crown decorated with stylized cobras.

The locals who were working with Howard Carter were spooked by the images of the snakes, because cobras were symbolic of the king's justice, notes the Smithsonian, and maybe also because they'd seen some version of that stupid mummy-unwrapping stage play. Then, later that day Carter's pet canary was literally eaten by a cobra, so that spooked the locals even more. Some of them believed the spirit of the dead king was warning the archaeologists away.

It's worth noting, though, that Egyptian cobras aren't exactly uncommon in Egypt, and they are attracted to villages, where they can easily prey on young chickens, rats, and — yes — canaries. So for every canary that died in Egypt the day King Tut's tomb was opened, there were probably a few thousand other small animals that also got eaten by cobras, and not because they had anything to do with the opening of a pharaoh's tomb. Still, the only cobra-prey that gained notoriety was that one little yellow canary, who happened to be unfortunate enough to get eaten at precisely the right moment in history.

Fake news!

If the story about the canary is even true, there isn't any proof that it is. According to Skeptoid (the Lords and Masters of Party-Pooping), the media was responsible for most of the stories about a curse on King Tut's tomb, and the media in the 1920s wasn't exactly known for its commitment to the truth if the truth might get in the way of a sensational story.

Evidently, the canary story was just one of a bunch of "curse" stories told by the papers — the papers also said all the lights in Cairo went off at the exact moment of Lord Carnarvon's death, and that his dog, which he'd left behind in England, howled and then died for no apparent reason, also at the exact moment of his death, reports the Examiner (via Itchy Fish). But then Skeptoid points out that those stories only ever appeared in the papers and not in any of the writings of people who mattered (like Howard Carter or any of those who worked with him), so they probably should not be believed. Even the canary story, wonderfully creepy though as it is, can be called into question just based on the fact that it's not something Carter himself ever wrote about.

Could you be a little more specific please?

Another popular legend is that Howard Carter and his team encountered a written curse in the antechamber. The curse was inscribed into a clay tablet and it went like this: "Death will slay with his wings whoever disturbs the peace of the pharaoh." Eek!

Carter pooh-poohed the warning and then failed to make any written note of its existence, and then evidently also lost it, since it has never been seen by anyone. That doesn't really seem very science-y, but according to Skeptoid, Carter and his team then went on to desecrate the tomb and take stuff out and behave in a most-definitely peace-disturby way. Believers rationalize the absence of the clay tablet from pretty much every historical record by claiming Carter just scrubbed all mentions of it so as not to upset the locals. Which is kind of silly since there's no evidence that Carter himself believed in the curse, and erasing it sort of goes against everything he stood for as an archaeologist.

Also there's the part where none of the deaths that have been loosely associated with King Tut's tomb had anything to do with wings, which means the curse was really not very specific. You would think, if you had the power to curse people across the sands of time, that you'd pick something pretty mind-blowing so that centuries later no one would be writing articles about how your curse wasn't actually the real deal.

I'll enact revenge on you later

So let's say there actually was a curse on King Tut's tomb, and the spirit of the dead pharaoh and/or whatever deities were charged with protecting him were poised to take down anyone who dared to disturb the sanctity of his tomb. Shouldn't the prime target of the curse be the dude who actually busted down the doors, let a bunch of noisy people inside, and then accidentally decapitated the boy king while trying to remove his golden death mask?

According to Time, King Tut was buried wearing "innumerable amulets of beauty and ghostly merit," and then there was also another cobra — this one was on his mummy's forehead along with a vulture, which was another deity meant to protect him in the afterlife. Before anyone saw all that, though, they saw the stub where his head had once been because in their eagerness to reveal the face of the boy king, Howard Carter and his workers tore his whole head off along with the mask they were trying to remove. So if ever there was a guy who deserved to be smited by a mummy's curse, it was Carter. But instead, the mummy seemed perfectly content to just kill canaries and make dogs howl. Carter himself not only kept on living, he also spent years excavating the tomb and further desecrating pretty much everything inside it, and he did it without any divine sanction. Maybe he had some sort of curse-repelling amulet he never told anyone about.

You are hereby cursed to live a long life and die of natural causes

Seventeen years after he opened the tomb of King Tutankhamun, Howard Carter finally succumbed to the mummy's curse. Yes, Tut got tired of watching his nemesis do unlucky things like achieving archaeological fame and touring the world as a lecturer and expert on Egyptian archaeology, as per Biography. So he decided to finally smite Carter by giving him lymphoma, and he maybe got mad at a lot of unrelated people, since roughly 1,000 people die every year from that particular disease, reports Cancer.net.

So if there was a curse, Carter didn't seem to get much of it, at least not for almost two decades after he actually found the tomb. Believers have an explanation for that, too, because that's just emotionally and mentally easier than letting go of their beloved theory.

According to Skeptoid, believers like to say Carter was indeed cursed: Cursed to live a long life wherein he would have to watch all his friends and colleagues as one by one they were taken down by a 3,000-year-old Egyptian corpse. Of course (with a couple exceptions), most of the curse's victims were more like casual acquaintances, as per Mental Floss, but whatever. The point is he was tormented for years after the tomb was opened. There's no evidence he actually felt tormented, but that doesn't mean he wasn't.

It wasn't tomb toxins, either

There's also the tomb-toxin theory, which goes like this: Pharaoh gets sealed in tomb, bacteria and other pathogens take hold and multiply, tomb is opened thousands of years later releasing said toxins into the lungs of unsuspecting archaeologists. It's a nice, tidy way to explain away mysterious deaths without acknowledging supernatural forces, but it's not a very solid theory.

According to National Geographic, labs have indeed discovered potentially dangerous molds growing on Egyptian mummies and tomb walls, including one that can cause bleeding in the lungs and another that can cause lung infections. That could explain one of the deaths — George Jay Gould died from pneumonia shortly after entering the tomb, writes Roger Luckhurst in "The Mummy's Curse." But most of the curse's other "victims" died from non-bacterial illnesses like cancer, murder, suicide, and falling down. And it seems odd that a deadly pneumonia-causing bacteria would only infect a single person when there were plenty of other people who spent a lot more time in the tomb than Gould did. One of those people was Sgt. Richard Adamson, who guarded Tut's burial chamber for seven years and then went on to live for another 53 years after that (via Live Science). Skeptoid also notes that if tomb toxins were a thing, there would probably be some sort of record of lots of people falling ill in other parts of Egypt, but there isn't.

Statistical probability and other boring stuff

You might still be clinging to the notion that if there weren't a curse, surely there wouldn't have been so many deaths that were directly linked to the opening of the tomb and/or the sarcophagus. So let's just break it all down. According to Live Science, a skeptic named James Randi (a professional party-pooper) wrote in his book "An Encyclopedia of Claims, Frauds, and Hoaxes of the Occult and Supernatural" that the average lifespan of a person who was involved in the opening of King Tutankhamun's tomb was more than 23 years. And these were mostly old guys, so that figure doesn't even represent a shortened lifespan. "This group died at an average age of seventy-three plus years," Randi wrote, "beating the actuarial tables for persons of that period and social class by about a year." So if a curse did exist, it seems to have given everyone an extra 12 months or so over what they'd normally get if they weren't cursed. Not bad.

But what about all those people who died within the first few years? Well, that can be explained by random chance. Pretty much any significant event involving a large number of people is going to have an occasional death associated with it because that's just a statistical probability. Yes, it's true, statistical probability is a total downer.

The definitive pooping of the cursed party

Then in 2002 someone finally got sick of listening to the world perpetuate the stupid myth of the mummy's curse, so they published an actual paper in an actual medical journal debunking the whole thing. According to the American Association for the Advancement of Science, an epidemiologist at Monash University in Australia named Mark Nelson spent a lot of time comparing the death rates of Westerners who were visiting Egypt at the time the tomb was opened with the death rates of Westerners who were actually present when the tomb was opened, and then he published it in the British Medical Journal, and no one laughed at him for talking with seriousness about a mummy's curse because all those medical journal people were also sick of hearing about it. Anyway, what he found was surprising: The people who entered King Tut's tomb died, on average, eight years sooner than the people in the other group.

Woo hoo! Curse proven! Except whoa, the people in the tomb-entering group were, on average, older and almost exclusively male, so the data had to be corrected to account for variations between the two groups. And when it was, Nelson found no statistically significant difference between the death rates of the tomb-enterers and the death rates of the tourists, so case closed. No mummy's curse. Consider this party pooped.