Kowloon Walled City: Once The Most Densely Populated Neighborhood On Earth

Lots of folks live in less-than-ideal conditions. Maybe you squeeze into a tin can because prices in New York City have gotten ridiculous, or you live with eight other working professionals in San Francisco for the same reason. Maybe there's a horrible upstairs neighbor who won't stop tromping around at odd hours or rolling bowling balls on the floor — because what else could that sound be? Maybe the building is old, the walls stained, the neighbors nosy, the mailbox broken, the shower vent pathetic, and many more complaints. But take heart: at least you don't sleep in your own kitchen — which is also where you work — next to a pile of warm chicken guts that you drop into dirty, oily water and sell for barely enough cash to keep the barely-functioning electricity on. Exaggeration? Not if you were one of the sad souls to live in what was once Earth's most densely populated neighborhood: Kowloon Walled City in Hong Kong.

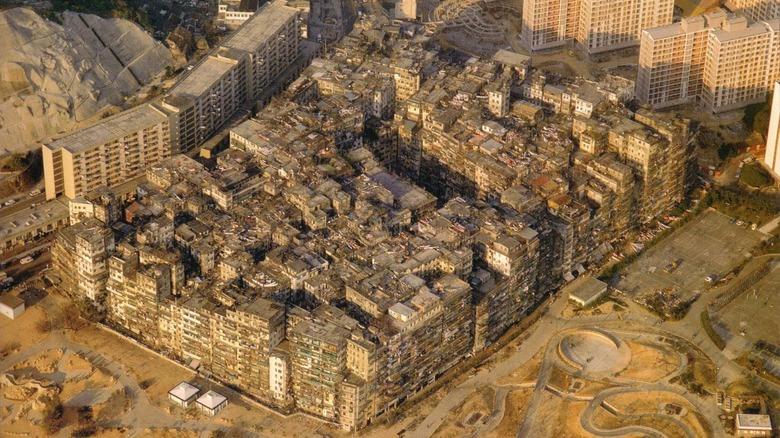

When we say that Kowloon was a neighborhood, please dispense with ridiculous notions of kempt grass in yards spritzed with generous spurts of summer water. We mean an absolutely debased, ghastly, filthy hell of dripping concrete boxes stacked on top of each other into one, huge, crumbling, lawless mega-box. As History Hit says, Kowloon once housed 50,000 people in a single structure covering less than 1/100th of a square mile. It was demolished in 1994, and its remains were converted into a park that can't hide its past.

[Featured image by Ian Lambot via Wikimedia Commons | Cropped and scaled | CC BY-SA 4.0]

A child of the Opium Wars

The history of Kowloon Walled City far predates its time spent as Earth's premiere dystopian nightmare. History Hit says that Kowloon began as a small, walled settlement during the Song Dynasty (960 to 1279 C.E.) when it served as an intermediary for trade routes. It was largely occupied by soldiers, per The Travel Club, and acted more like a fort than anything. It held this role all the way to the 19th century.

Come the 19th century, we got the seriously ugly Opium Wars between the Chinese and British empires when China fought to free itself from the drug dependency foisted on it by the British empire. The Collector tells us that after the First Opium War (1839 to 1842) and Second Opium War (1856 to 1860), the Chinese government relinquished control of Hong Kong to Britain in 1898 under a 99-year lease. Kowloon, however, remained exempt from this agreement — it belonged to China but remained in British-controlled Hong Kong. This formed the foundation for every single administrative, legal, regulatory, law enforcement, etc., problem that caused Kowloon to metastasize into a festering mega-tenement.

During World War II, Kowloon lost its eponymous walls when Japanese troops stripped the city for materials. When World War II ended, the Chinese Civil War began, and war refugees found an easy hide-out in nearby Kowloon. The British government wanted no part of the conflict, however. They refused to exercise control over Kowloon, and so did China.

[Featured image by Wellcome Images via Wikimedia Commons | Cropped and scaled | CC BY-SA 4.0]

Unchecked and unregulated construction

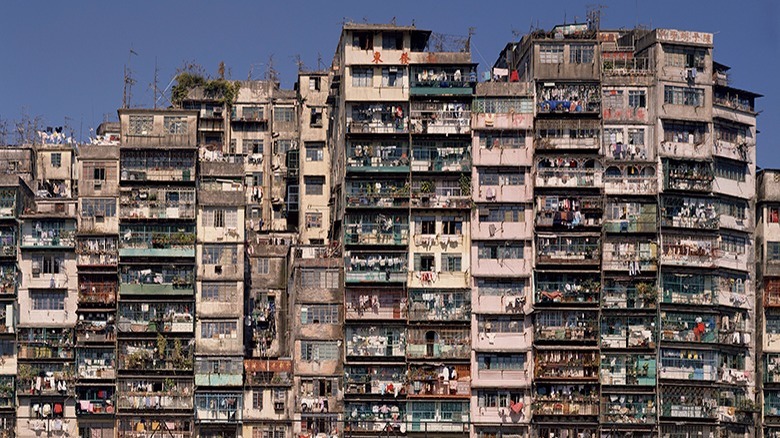

The 1950s and '60s saw Kowloon Walled City steer towards the form it would take in the future. The Collector says that Kowloon became a haven for squatters and the impoverished. Locals, non-professionals — anyone at all, really — started building within its perimeter. High-rises grew higher, tighter, closer, and by the 1970s all but fused into one, single, disjointed, off-kilter, pell-mell, cement superstructure 14 stories high. No architects designed it, no regulatory bodies managed it, and no one oversaw its daily operations. The Travel Club says Kowloon mutated into an "enclave of opium parlors, whorehouses, and gambling dens" ruled by triads — Chinese crime syndicates. "Police, health inspectors, and even tax collectors feared to tread" within its boundaries, especially at night. By 1973 10,000 people lived there. Less than 20 years later that number had ballooned to 50,000.

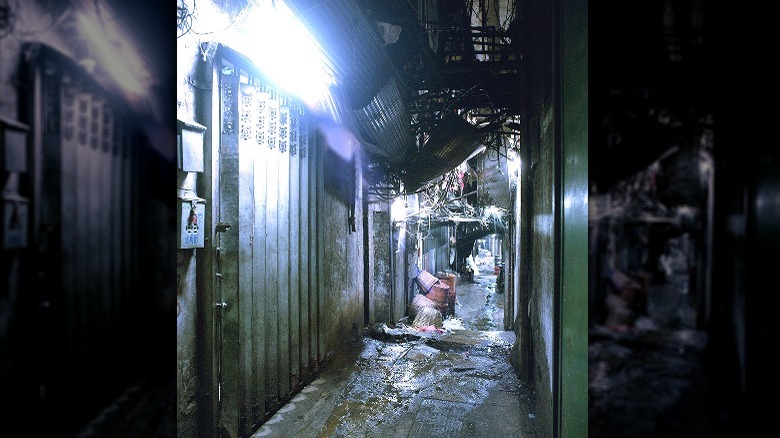

Per The Collector, Kowloon took on the name "Hak Nam" in Cantonese, or "City of Darkness" for its lightless, dripping hallways that received actual street names. People entered Kowloon on the lowest level carrying umbrellas, as The Travel Club shows, while those who could access roofs used them for exercise, gardening, and sports like pigeon racing. Folks also used roofs to dump trash, old mattresses, shattered electronics, etc., because Kowloon had no waste disposal services. Electric wires often ran outside to prevent fires, while 77 water pumps delivered water to the upper levels and down through apartments. Between it all huddled actual, whole families with children.

[Featured image by Ian Lambot Images via Wikimedia Commons | Cropped and scaled | CC BY-SA 4.0]

Squalor and loyalty

Much of our information about daily life in Kowloon Walled City comes from "City of Darkness: Life in Kowloon Walled City," published in 1993, the year Kowloon was eventually demolished. Largely a book of investigative, on-site photos of Kowloon's apartments and corridors, it depicts a gobsmacking clutter of heaped trash, moldy surfaces, ceilings sagging from decay, and much more. Sex workers shared walls with Evangelical churches, fish ball-making factories with pornographic film theaters, snake meat-selling establishments with pharmacies, and textile weavers with mahjong dens. The Travel Club says that apartments cost about $35 Hong Kong dollars a month, or $5 U.S. Many of them held families.

Interestingly enough, many of those families — regardless of what drove them to live in Kowloon — remember their time growing up in the city fondly. "We ate from a board laid over the knitting machine and sat on the bed," the Travel Club quotes former resident Heung Yin-king, who lived on the fourth floor along Tai Cheng Street. "Everyone got along, and it was great to have so many kids to play with." Kids would play in the hallways and on rooftops, and jump from roof to roof barefoot, as we can also see in pictures on Atlas Obscura. On The Travel Club, former resident Ida Shum described Kowloon's close-knit community. "People who lived there were always loyal to each other," she said. "In the Walled City, the sunshine always followed the rain."

[Featured image by Ian Lambot Images via Wikimedia Commons | Cropped and scaled | CC BY-SA 4.0]

Pulverized to dust

As Atlas Obscura says, Kowloon Walled City and its inhabitants remained pawns in a back-and-forth power game between Britain, Hong Kong, and China to the very end. Come the late 1980s and early '90s, the U.K.'s 1898, 99-year lease on Hong Kong was soon due to expire. In 1963 Hong Kong authorities had moved to demolish Kowloon — perhaps because it was physically unsightly, or perhaps because it was a reminder of the power that China exerted over Hong Kong. As soon as the demolition plans went public, however, Hong Kong officials met a resident-led "Kowloon City anti-demolition committee." But by the time the 1980s rolled around, the government kept their second round of demolition plans private.

On January 14, 1987 — when Kowloon was reaching its maximum occupancy — Hong Kong stealthily moved in, blocked off the whole city, and took a census. In order to keep things as smooth as possible they planned to provide financial compensation to residents, which doubled as a bribe to get them to leave. The compensation package equaled $2.76 billion, which equated to about $380,000 per individual apartment. This was enough for most, and come 1992, police swarmed the structure to remove the last remnants of inhabitants. Demolition started in March 1993, and it took a year to pulverize Kowloon to dust. In the end, the compensation strategy meant that those people who dwelled, laughed, and suffered in Kowloon walked away with enough to restart their lives elsewhere.

[Featured image by Roger Price Images via Wikimedia Commons | Cropped and scaled | CC BY-SA 2.0]

Cyperpunk and a green park

Kowloon Walled City has inspired an absolute horde of writers, artists, filmmakers, and more. Notably, Atlas Obscura says it inspired William Gibson's 1984 novel "Neuromancer," which consolidated sci-fi ranging back to the '60s into one, refined, distinct subgenre: cyberpunk. "Blade Runner," "Ghost in the Shell," "The Matrix," the "Shadowrun" tabletop and video game series, the newer "Cyberpunk 2077" game: all of these and more — and their entire cultural influence and impact — tie into the "Neuromancer" lineage and Kowloon. Kawasaki, Japan, even used to house a multi-floor Kowloon-themed arcade full of the same rusted metal, neon lights, decayed walls, and ersatz technology we've come to associate with the cyberpunk sub-genre, as Forbes shows.

As far as Kowloon's grounds are concerned, a beautiful green park now occupies the space where the city once stood. Comparing aerial pictures of the park (above) to Kowloon at its densest, you can see the same circular ring that once marked the southern edge of the city. Kowloon Walled City Park is open to the public year-round, and beyond remnants of the city's former South Gate has guided tours and a model of Kowloon's Jenga-like cluster of towers. Atlas Obscura says that the park, in stark contrast to Kowloon, was designed as a meticulous and manicured Jiangnan garden, a traditional type of Chinese garden discussed in detail on Yada. But for those who once lived there, and the rest of us through literature and film, Kowloon has never really vanished.

[Featured image by Wpcpey Images via Wikimedia Commons | Cropped and scaled | CC BY-SA 4.0]