Messed Up Things That Actually Happened In The Victorian Era

For everything that's changed in the decades since the rule of Queen Victoria, there's one thing that definitely hasn't changed: people are still seriously messed up, just in different sorts of ways. Sure, by the time Victoria took the throne, the world probably felt it had graduated from the Dark Ages and the Middle Ages to become all civilized and modern and whatnot, but ... in reality? Not at all. The Victorian era was seriously nuts. Here are some of the weirdest, strangest practices from the Victorian Era that you never knew about.

Death photography

The Victorians were a little bit obsessed with death. Sounds messed up, but it makes sense when you consider the smorgasbord of diseases that stalked Victorians—measles, scarlet fever, diphtheria, rubella, typhus, and cholera. It was a sort of gauntlet of death that children and adults alike ran through every day. Those very real threats and sense of loss led to people keeping memento mori (Latin for "remember you must die") trinkets, like locks of hair and photos of the dead.

Remember that photographs were still a fairly technology, and they were only starting to become affordable in the mid-1800s. As such, it was often only when something tragic happened that people would think to immortalize their loved ones in photographs. That gave rise to the seriously creepy trend of death photography.

The bodies were often kept at home for the mourning period, and photographs were staged with not just the deceased, but their parents or siblings, sometimes posing as if everyone were still alive. Children sat with their dead parent, parents held their dead children...you get the idea. Some photos even show faces with open eyes that were painted right on the photo. They're eerie, creepy, and incredibly heartbreaking, especially when you consider these photos capture the one and only chance that many grieving families had to get a photo of their loved ones.

Child emigrations

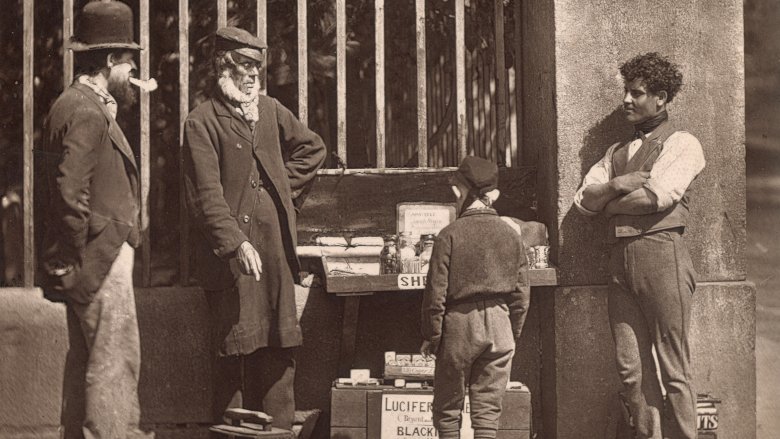

If you've ever seen any Victorian period piece, you've seen the adorable but filthy children that live in the streets, picking pockets and causing a general sort of trouble. The plight of orphan children was very real, and according to writer and historian Sarah Wise (via Spitalfields Life), estimates suggest that there were around 30,000 children were living on the London streets in 1869.

Wealthy philanthropists took up the cause, including Miss Annie Macpherson. Macpherson set up some schools to teach the kids useful skills, but the problem soon became overwhelming. So she changed gears and became a champion of the disturbing practice of emigration: kids were pulled off the streets and out of workhouses to be shipped overseas to British colonies. Many ended up laboring as farm help or working as domestic servants, and by 1904 Macpherson alone had sent 12,000 children to Canada.

The Maritime Archives & Library of the National Museums Liverpool says children were also sent to Australia and New Zealand, and between 1870 and 1914, 80,000 kids were sent just to Canada. The practice was hugely controversial even at the time, as the agencies rarely followed up on the kids they placed overseas and investigations showed that contrary to the lofty goals emigration groups had, their lives rarely actually got better.

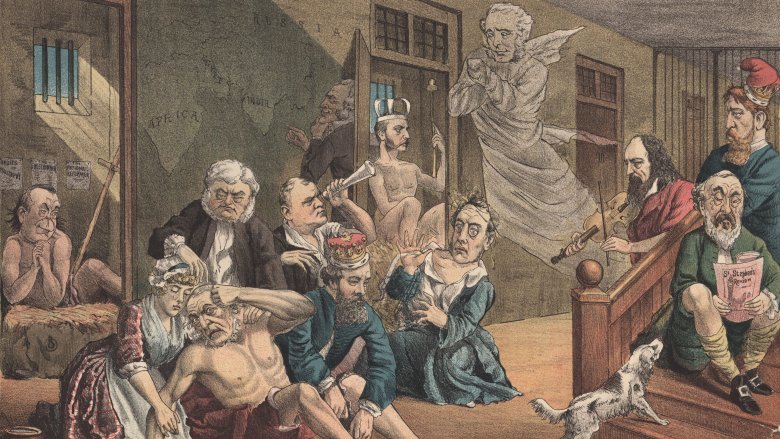

The supposed causes of mental illness were ... insane

According to Cornwall's Bodmin Hospital, the population of England's insane asylums skyrocketed through the 19th century. Apparently most of the patients fell under three labels: the manic, the melancholic, and those with dementia. The symptoms of those diagnosed with the Big Three varied, and they weren't the only messed up reasons you could be committed—nor was England the only place that went a little crazy with all the crazy.

West Virginia's Trans-Allegheny Lunatic Asylum's records of common causes of mental illness for patients admitted between 1864 and 1889 reads like either a college student's to-do list or a really good Friday night. On their list were offenses like laziness, novel reading, superstition, an immoral life, and intemperance, along with every single kind of self-pleasure you can imagine.

Women weren't left out, either, and there are some equally bizarre possible causes of mental illness. Those include things like "imaginary female trouble" and "hysteria," along with "rumor of husband murder" and "fits and desertion of husband." Yikes.

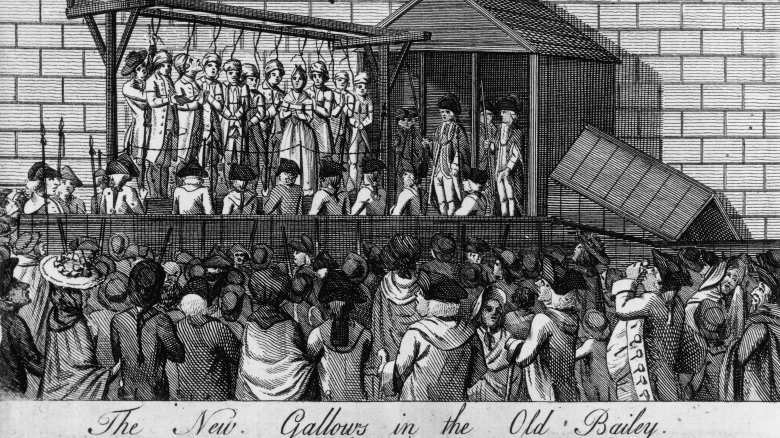

You could make a living as a grave robber

We can all agree it's better that medical students learn on cadavers before they start poking around inside living humans, but Victorian-era schools were faced with a problem. Historic UK says that the only bodies they could legally dissect were those that had belonged to someone who had been executed for a crime, and in 1823, Britain passed a law that made fewer crimes end in the death penalty. Doctors-in-training still needed to learn, and that meant they needed to get their cadavers somewhere else.

That somewhere else was the cemetery, and if you want some seriously grim reading you can find it in The Diary of a Resurrectionist. Written by James Blake Bailey of the Royal College of Surgeons of England, he gives a great insight into the everyday life of a resurrectionist—the label given to the people who dug people out of their graves. Not only did they get a price for each one, but they were also given a fee to be kept on retainer and a fee after a successful delivery. There was a massive market in selling teeth, too, usually to dentists.

The fresher the body, the more in demand it was. So when cemeteries started installing watchtowers and guards, body snatchers had to get creative. Some—like William Burke and William Hare, the most famous of the era's snatchers—just turned to murder to get the freshest samples possible. No digging required.

A beauty routine included things like ammonia, arsenic, and lead

Standards of beauty might change from generation to generation. But Victorian beauty routines read like something out of a chemistry textbook—specifically the part near the back where they list all the stuff that'll kill you.

Harper's Bazaar ran a column called "The Ugly Girl Papers: Or, Hints for the Toilet" (via Atlas Obscura). It offered practical beauty advice, but today we'd recognize it as being insanely dangerous. White skin was all the rage, and women achieved that by washing their faces with ammonia, then covering them with lead-based paint. And don't think you could get away with going bare-faced at night, either, because in order to keep that fresh-faced look, the column suggested rubbing some opium on before bed. For those who were really committed, Sears & Roebuck sold a product called Dr. Campbell's Safe Arsenic Complexion Wafers. Yes, it was arsenic, and yes, women were instructed to eat them.

If you were unlucky enough to have thin eyebrows and eyelashes, a nightly smear of mercury could help with that. And speaking of eyes, watery eyes were all the rage, too...for some reason. To achieve that look, women could use lemon juice, perfume, or belladonna as eyedrops. The latter did, of course, cause blindness, but people have been suffering for beauty for ages.

Divorce wasn't a thing, so men sold unwanted wives

Divorce wasn't allowed in England until the Matrimonial Causes Act of 1857, but people have been having marital difficulties for as long as they've been getting married. Since you couldn't just sign some papers and be on your merry way, people needed to find another way out. As a result, wife-selling became a completely legitimate way to get out of a marriage, and it continued well through the 19th century, particularly in rural Britain.

According to research done by Lauren Padgett from Leeds Trinity University, wife sales could happen in public or in private. But the public sales were quite the spectacle. The husband typically put some kind of lead rope on his unwanted wife, took her to a public square, and asked for offers. Sort of like eBay, but with your wife instead of an old smartphone.

Records suggest that the wife had veto power over the sale, and sometimes it was for cash. Prices varied: one wife was sold in Selby in 1862 for a pint of beer, while others seem to have gone for a decent amount of cash.

And according to economist Peter Leeson (via Motherboard), it wasn't necessarily a bad deal for the wives. Not only did it give them a way out of a bad situation, but they could also trade up into a marriage where they were valued—one that could possibly be with a rich older man who wasn't part of the traditional marriage pool. So...yay wife-selling? Kind of?

The Abode of Love was a crazy cult

The Victorians have a bit of a reputation as being at least slightly repressed, so you can only imagine what most people must have thought when a crazy free-love cult popped up in 1846. It was founded by Henry Prince, a one-time clergyman who started recruiting followers—mostly rich, unmarried women—by convincing them to "donate" all their cash to him so that he could build what he called "The Abode of Love." According to The Telegraph, that abode was a group of cottages protected by a 12-foot wall. The community was officially called Agapemone, and was built mostly on the inheritance of five spinster sisters who Prince arranged to have marry some of his followers. Prince himself moved into a 16-bedroom house, and while he insisted on chastity and abstinence from his followers, he was getting busy with members of the community in very public ceremonies he claimed were completely necessary.

In spite of his insistence that he was immortal, Prince died in 1889. John Hugh Smyth-Piggot took over as cult leader, left the community's compound to declare that he was the Second Coming of Christ, and was almost immediately run out of town and back to the safety of the community. He lived there as a "heavenly bridegroom" among his "soul brides" until he, too, proved not as immortal as he claimed when he died in 1927. The cult hung on a bit longer, and didn't disappear until 1956.

Corpse medicine was still a thing

"Corpse medicine" is exactly what it sounds like, and for hundreds of years people believed that consuming certain parts of the human body was a miracle cure for whatever ailed them. A popular prescribed cure-all was human skull, and — when mixed with chocolate — it was believed to treat apoplexy.

Corpse medicine was at its height in the 16th and 17th centuries, but Smithsonian Magazine says it persisted well into the Victorian era. Medical texts specify which morsels are good for which ailments, and there were recipe books that explained how to prepare the pieces, too. One text from 1847 prescribes a bit of skull (specifically, the skull of a young woman) mixed with treacle as a treatment for epilepsy. (It didn't work.) There was also a belief that something called a thieves' candle could cause paralysis, if you were into that sort of thing. They were made with human fat, and there are records of them being made into the 1880s.

Executioners were often linked to corpse medicine, and it wasn't uncommon for them to do double duty as bringer-of-death and healer-of-the-poor, selling pints of warm blood from very recent clients. Look on the bright side — you might hate your doctor, but at least he'll send you to a pharmacist instead of a hanging to get your medicine.

Mummies were used for all kinds of disturbing things

The whole 19th century was defined by a messed-up British obsession with all things Egyptian, and you can still see the traces of Egypt-o-mania reflected in the era's architecture. Mummies were front and center when it came to the Victorians' weird fetish, and it wasn't enough to do something normal like put them in a museum. According to The Journal of Art in Society, paint-makers used ground-up mummies as one of the ingredients in brown paint aptly named Mummy Brown. It was hugely popular throughout the Victorian era, even though some people thought turning mummies into paint was wrong while others said it made for poor quality paint, because priorities.

There were other weird things mummies were used for, too. In 2007, a forensic scientist tested the contents of a jar found in 1867 in a Victorian-era Paris pharmacy (via the BBC). The label identified the contents as the remains of Joan of Arc, and while that seemed unlikely, the test results found something even more unlikely: it was made of mummy, dating back to some time between the third and seventh centuries BC. It was likely "prepared" not long before it was "found."

They were also used as advertising draws. In 1886, a mummy said to be the very same Pharaoh's daughter who had saved the life of baby Moses was put on display in a candy store in Chicago, because there's nothing quite like a mummy watching you as you pick out your bonbons and lollies.

Food additives were insane

When we start talking about the worst things you could find in the foodstuffs of Victorian England, we're not even going to get into sanitation, aside from saying it wasn't uncommon for bakers to knead dough using their feet, because that needs a mention. Let's talk about the stuff they used to put into food on purpose.

The Royal Society of Chemistry says food safety and industry regulation really got its start in the Victorian era, thanks to the tendency to use potentially deadly additives. Chalk and alum were sometimes added to dough to make bread whiter, and it wasn't unheard of to have things like pipe clay, plaster of Paris, or sawdust added to the mix. Brewers sometimes added strychnine to their beer so they could cut back on hops, and lead was all over.

Professor Anthony S. Wohl of Vassar College says red lead was used to color Gloucester cheese, and lead was added to cider, mustard, wine, sugars, and candies. Copper sulfates were used in preserving fruit, jams, and wine, mercury was used in candies, and let's talk about ice cream, which University of Tasmania professor Dr. Bruce Rosen says got popular in the 1880s. The stuff you'd get on the street sometimes wasn't made with milk, but just a water-and-chalk mixture. As if you didn't have enough to worry about with all the cholera, typhoid, and diphtheria...your food was just making it worse.

Amelia Dyer and the baby farmers

Just how dark can humanity get? Let's check out the Victorian-era baby farmers.

Psychology Today has the details. At the time, most people were a little shaky on how not to get pregnant, and when they did, it could be the stuff of life-changing ruin. An entire group of women made a living taking care of these unwanted children or acting as brokers to get them into happy homes—for a fee. Some were loving people who legitimately helped mother and baby. Others...not so much.

There's headline after headline detailing the death counts attributed to the worst of the baby farmers, women who would take the child and their fee for finding him or her a new home...and then just off the baby. Trials would cite counts of dozens of infanticides, and one of the worst (that we know of) was Amelia Dyer, who provided her services to desperate mothers for more than 30 years. According to the BBC, she charged the equivalent of $10,000 in today's cash, and at the time of her capture took in an average of six babies every day. She was convicted after the body of Helena Fry was fished out of the Thames, and she admitted to police every one strangled with tape was "one of mine." It's not known how many she killed, but the number is certainly in the hundreds.

Hysterectomies were performed as treatment for mental illness

There's no shortage of reasons a woman could find herself committed to an insane asylum in the Victorian era, and once she was there, what were doctors to do with her? According to the teachings of Dr. R. Maurice Bucke, the thing to do was to get rid of what was causing his patients' madness: their reproductive organs.

Bucke was the superintendent at the London Asylum for the Insane from 1877 to 1902, and according to their histories he performed more than 200 surgeries on women in the hopes of knocking loose whatever was driving them batty. That included 16 hysterectomies and 22 operations undertaken to move the uterus back to its rightful position because maybe it had wandered off. (We're totally not making that up.) In 1898, he gave a speech to the American Medico-Psychological Association, detailing some of his cases, like a woman identified as LM. She had violent tendencies and seizures, was diagnosed with "intense irritation of both ovaries" and after they were removed, she "was quite well."

We should also note there were plenty of doctors who were skeptical about the idea, but that didn't stop Bucke from being held in high esteem as a leader in Canada's medical community as well as in London.

Athletes used performance-enhancing drugs...like strychnine

For as long as there's been sport, there's been the desire to be the best. That's not odd, but what is odd is the doping Victorian athletes did for some weird sports, like pedestrianism — long-distance walking. Walkers would cover hundreds of miles over the course of a few days, and they did it by going around and around a track (and around, and around...).

According to The Guardian, a pedestrianism scandal kicked off in 1876, when American competitor Edward Weston tried to cover 115 miles in a day. (He finished less than 6 miles short.) In order to stay awake, Weston chewed coca leaves throughout the "race" and the outrage wasn't because he used coca, it was because he was also a participant in a physiological trial and he'd supposedly invalidated the results with coca. At any rate, Weston's chew was just one of the ways Victorian athletes fought off fatigue and muscle aches. They also used "tonics," and those were anything from cocaine to alcohol to strychnine.

Yes, strychnine. It's rat poison, and in high enough doses it pulls the facial muscles into a smile as it shuts down the respiratory system...while a person is still conscious. According to io9, athletes would inject strychnine to cause an effect not unlike coffee, but deadlier. Why not just drink coffee?

Theater stampedes, fires, and deaths

You can't go into any public building without seeing emergency exits and maximum capacity signs. But safety hadn't been invented in the Victorian era, and it was a string of tragedies that made people decide something needed to be done to keep this from happening.

In 1876, the Brooklyn Theatre burned—along with 278 people—after a lantern fell over on stage. There was nothing wrong with the building by the standards of the time, but when fire and panic both broke out, people trying to flee were trapped in a staircase. According to Atlas Obscura, 103 were never identified, but the public outpouring of grief was so great a monument was erected over a mass gravesite.

The worst was arguably the Victoria Hall Disaster of 1883. Around 2,000 children—most 7 to 11 years old—crowded into Victoria Hall to see some traveling entertainers. At the end, the group announced children with certain numbers on their tickets would be given prizes, and the ensuing stampede trapped children in the stairwells. It took half an hour to dislodge the crowd, and 183 kids were deceased. Smithsonian Magazine says it was this tragedy that sparked the invention of the push-bar emergency exit, but this simple, life-saving invention wasn't immediately implemented...at a massive cost. In 1903, the lives of 602 people might have been saved when the Iroquois Theater burned in Chicago. It had been built only five weeks before.

Their newfangled gas lights were dangerous

Can you imagine being the first one on the block to have these newfangled things called indoor light fixtures? We can't, but the Victorian era saw a huge advancement from candlelight to indoor, gas-fueled light fixtures that changed the way mankind saw the night.

But it came at a messed-up cost, and according to Country Life, the development first came on a commercial scale that would allow employees to work longer and later. That's the first strike, and the second came when these lights started popping up in homes. Not only was there cutthroat competition resulting in some serious sabotage of gas lines, but when that sabotage happened in homes it led to fires, explosions, and leaking coal gas, which was essentially methane, hydrogen, sulfur, and carbon monoxide. You've seen those heavy drapes covering Victorian windows, right? How fast do you think all that gas started building up? It's entirely possible that all (or, at least some) of the fainting going on during the Victorian era wasn't just people being dramatic, it was the gas.

The gas lights—and toxic fumes—have also been linked to the Victorian obsession with ghosts and the occult. According to The Guardian, hallucinations caused by the gas fumes is one of the things (among a number) that led to the rise of ghost stories and spiritualism. Hey, that's a bonus, right?