Are American Presidents Allowed To Get Drunk?

There was a time when drinking and public life went hand in hand. Throughout the 1970s and 1980s, late-night talk shows — like "The Tonight Show Starring Johnny Carson"— typically showed guests drinking freely, a vice that had glamorous connotations at the time. And it was not just in the world of entertainment that booze flowed freely — politicians, too, have been known to enjoy the odd public tipple. Former Russian leader Boris Yeltsin became something of a figure of fun in the 1990s for his drunken public appearances, which included dancing, singing, and outrageous comments to the press — incidents that would occasionally bring his American counterpart, Bill Clinton, to tears of laughter.

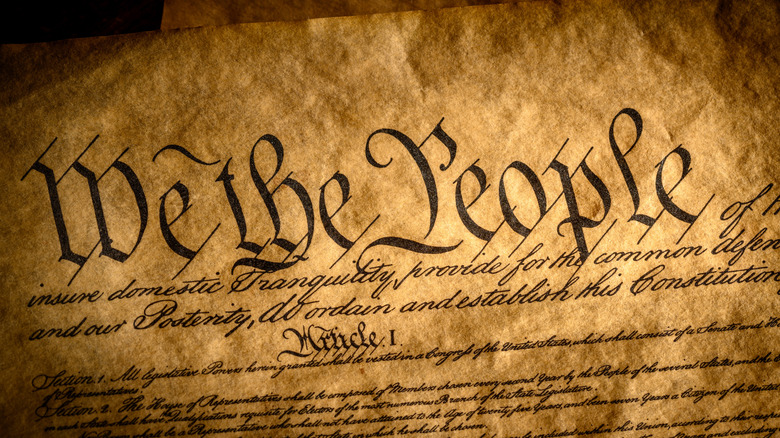

But the thought of seeing a sitting president of the United States drunk while in office is difficult to imagine today. Nevertheless, there is reportedly no hard and fast rule in the Constitution that prevents American presidents from drinking, which is just as well, as many of them have proven to be partial to alcohol to varying degrees.

The long history of drinking at the white house

The presence of alcohol in the corridors of American power has been well documented. Ulysses S. Grant had a complicated relationship with alcohol: His reputation as a big drinker was established during his military years, though he reportedly cut down on his alcohol intake once he won the presidency. George Washington, meanwhile, had his own personal beer recipe, which has been replicated by modern brewers.

More recently, the drinking habits of various 20th-century presidents have also made it into the history books. One famous anecdote concerns Lyndon B. Johnson, who was known to unwind from his presidential duties by driving his collection of classic automobiles around his ranch, accompanied by various aides and secret service personnel. However, on such occasions Johnson was also typically drinking behind the wheel, sipping Cutty Sark whiskey on the rocks as he drove.

Other presidents proved to be less capable of staying in control while intoxicated. Richard Nixon developed a reputation among his colleagues for having a low tolerance for alcohol but drinking nonetheless, especially after the Watergate scandal threatened to unravel his administration. Sometimes, Nixon's aides would have to step in and take the president's phone calls if he was too drunk to hold a conversation.

Drinking and the 25th Amendment

While there is no law against American presidents drinking to excess, there is in fact a relatively recent constitutional mechanism that could prevent alcohol-affected leaders from endangering the United States through erratic decision-making or actions.

The 25th Amendment of the Constitution of the United States was ratified in 1967 and outlines the process by which a sitting president might be replaced in the event of sudden death or resignation from their post. But the fourth part of the Amendment also explains how presidents who are unable to fulfill their duties due to being either mentally or physically incapacitated — and unable to remove themselves from office — might have their executive power transferred to the vice president, who becomes acting president with the explicit approval of the cabinet.

Section four of the 25th Amendment, therefore, differs from impeachment in that the president for whom it is invoked technically remains in post and may return to their duties once they have regained their faculties.