The Best And Worst U.S. Presidents, According To Historians

In 2021, C-SPAN published its latest presidential historians survey, which asked a panel of experts to rank the previous 45 U.S. presidents in the following categories: public persuasion; crisis leadership; economic management; moral authority; international relations; administrative skills; relations with Congress; "vision and setting an agenda," "pursued equal justice for all," and "performance within context of times." Then, these 10 "individual leadership characteristics" were combined to calculate an overall score for each president — the higher the score, the better the president.

The results may come as a surprise. Obviously, Abraham Lincoln and George Washington are heavyweights in this arena. But what about JFK and Ronald Reagan? Where does a 21st-century president, such as Donald Trump, rank compared to old Civil War figures such as Andrew Johnson and James Buchanan? With the 2021 C-SPAN survey as a guide, here are the six best and six worst presidents of the United States.

Harry S. Truman - Best (713)

While serving as president from 1945 until 1953, Harry Truman led the United States through the final months of WWII, funded Europe's recovery with the Marshall Plan, and came to the defense of South Korea in 1950, beginning the three-year Korean War (via History). Born in Lamar, Missouri, on May 8, 1884, Truman worked in a bank and later managed the family farm before enlisting in April 1917, following the United States' entry into WWI. During the conflict in France, Truman's nascent leadership skills were tested and won praise, with a unit of artillerymen under his command (via Britannica). Throughout the 1920s and early 1930s, Truman served in Missouri state politics and built upon his trustworthy reputation, which grew further after his appointment to the Senate in 1935.

Truman became Franklin D. Roosevelt's running mate in the 1944 election, which they won with 53 percent of the vote. However, Truman wouldn't be vice president for long. On April 12, 1945, Roosevelt died of a cerebral hemorrhage, leaving Truman the responsibility of ending WWII and containing the emerging threat of the Soviet Union.

Like almost all presidents, Truman's leadership experienced peaks and troughs. His approval rating rode high in 1945, peaking at 87% in June. By January 1953, however, it had slumped to just 31% due to the Korean War, anti-communist hysteria, and accusations of corruption. History has been kind, though. C-SPAN scored Truman well across the board, with particular strengths in crisis leadership (80.1), international relations (78.3), and "performance within context of times" (77.4).

Dwight D. Eisenhower - Best (734)

Famous for his role as supreme allied commander during WWII, Dwight D. Eisenhower succeeded Truman as president of the United States on January 20, 1953. A proponent of "Modern Republicanism," Eisenhower stated his ambition to lead the United States "down the middle of the road between the unfettered power of concentrated wealth . . . and the unbridled power of statism or partisan interests" (via the Miller Center).

Eisenhower favored a small government philosophy, but he still increased the minimum wage, invested in low-income housing, and established the interstate highway system, building some 41,000 miles of roadways. He also presided over a growing economy, with low unemployment, and wage increases of 45%. In short, Eisenhower's "hidden hand" leadership philosophy, which delegated responsibility and credit to his subordinates, worked to build infrastructure and healthy national finances. However, Eisenhower's understated leadership proved to be indecisive on certain social issues. For example, the president was rather muted on race relations: He may have signed two civil rights bills, but their effect was piecemeal compared to the change of the 1960s.

According to historian Chester J. Pach, Jr. (via the Miller Center), some critics dubbed Eisenhower a "do-nothing president." However, he remained popular with the American people and left office with an average approval rating of 65% (via Gallup). He is popular among historians, too. After ranking 22nd in 1962, Eisenhower rose to 11th place in 1994, 8th place by 2009, and in 2021, the 34th president was ranked 5th by C-SPAN's survey, joining the nation's most revered leaders.

Theodore Roosevelt - Best (785)

According to historian Lewis Gould (via NPR), the prevailing view of Theodore Roosevelt was once set by Henry Pringle's 1931 biography, which gave the impression that Roosevelt was "fun to watch but ultimately inconsequential in the nation's history." However, this idea was transformed in 1960 by John Morton Blum's "The Republican Roosevelt," which described the 26th U.S. president as having a "sharp instinct" for advancing his agenda and a "strong genius for the art of governance."

Today, Theodore Roosevelt is remembered for being what historian Sidney Milkis describes as "the first modern president" (via the Miller Center). Roosevelt changed the meaning — and the power — of the presidency, by shifting authority from Congress to the Oval Office through political machinations, and the sheer force of his personality. Roosevelt used this new authority to advance his notions of progressivism, which championed government regulation in many areas of the nation's governance.

Despite his domestic strides, Roosevelt may be best known for his nationalist foreign policy, which he summarized with the proverb "speak softly and carry a big stick" (via National Geographic). He followed the legacy of his predecessor, William McKinley, and bucked the tradition of isolationism, strengthening the U.S. Navy and governing new overseas territories, including Hawaii, Puerto Rico, Guam, and the Philippines. He also laid the political groundwork for the Panama Canal and brokered peace deals across the world, namely the Russo-Japanese war of 1905 (via the Miller Center).

Franklin D. Roosevelt - Best (841)

Professor William E. Leuchtenburg (via the Miller Center) wrote that Franklin D. Roosevelt may "have done more [to] change American society and politics than any of his predecessors in the White House, save Abraham Lincoln." This is because FDR led the United States through two catastrophes: the Great Depression and the Second World War. In response to the first disaster, Roosevelt delivered his "New Deal," which, while being "chaotic, confusing, and contradictory" in Leuchtenberg's opinion, was also a seminal program that "[laid] the foundation for future stability and prosperity."

The second great crisis of FDR's presidency was similarly complicated. Isolationism had become a dominant force in the United States following WWI. Consequently, the U.S. looked on as Japan invaded China, Italy invaded Ethiopia, and Spain tore itself apart during its bloody civil war. FDR disagreed with this outlook and, like his fifth cousin Theodore, believed the United States should be an active player on the international stage (via Office of the Historian).

However, FDR's convictions could not overcome several Neutrality Acts passed by Congress in the 1930s. Roosevelt was clear in his support for Great Britain, though. When Nazi Germany occupied continental Europe in 1940, FDR supplied everything to Britain and its allies short of war, bolstered in 1941 by the Lend-Lease program (via the Office of the Historian). It would take Pearl Harbor to finally overturn America's isolationism. C-SPAN ranked FDR as the third-best president, awarding him a score of 91.6 in the category of crisis leadership.

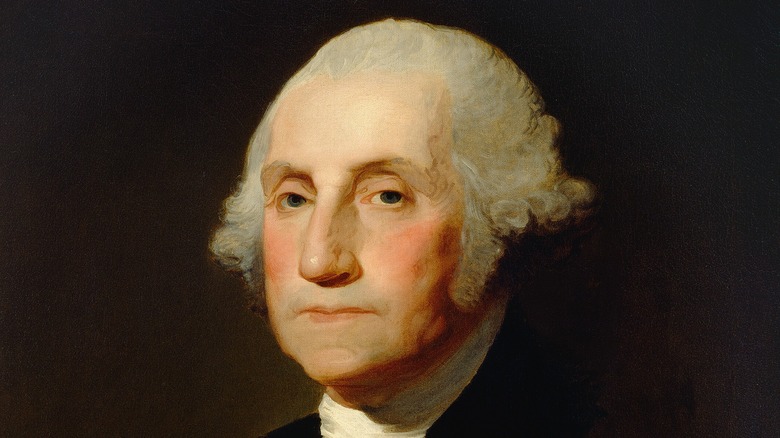

George Washington - Best (851)

The U.S.'s first president, George Washington, is remembered by historians as the individual who defined the style and parameters of the office. During his eight years in office, Washington was a model of restraint who, in the words of historian Lindsay M. Chervinsky (via the Miller Center), was "always mindful of the principles of republican virtue, namely self-sacrifice, decorum, self-improvement, and leadership."

The most famous American figure in the Revolutionary War, Washington served as commander in chief of the Continental Army, a position that could have segued into the country's leader following the United States' victory on September 3, 1783. However, Washington resigned his post on December 23 of that year and returned to Mount Vernon, where he intended to live as a gentleman farmer (via Britannica).

However, Washington soon grew concerned about the state of the fledgling union, writing privately that "something must be done, or the fabric must fall, for it is certainly tottering." Consequently, after much hesitation and doubt, Washington accepted his nomination as the first president of the United States.

No other American at that time had Washington's character and profile: He commanded great respect both at home and in Europe. Yet Washington was a reluctant leader who doubted his abilities and was wary of public life. Still, he led the nation with the sagacious caution for which he was known and has remained among the most lauded Americans ever since. C-SPAN scored Washington 91.9 for crisis leadership, 92.7 for moral authority, and 95.6 for "performance within context of times."

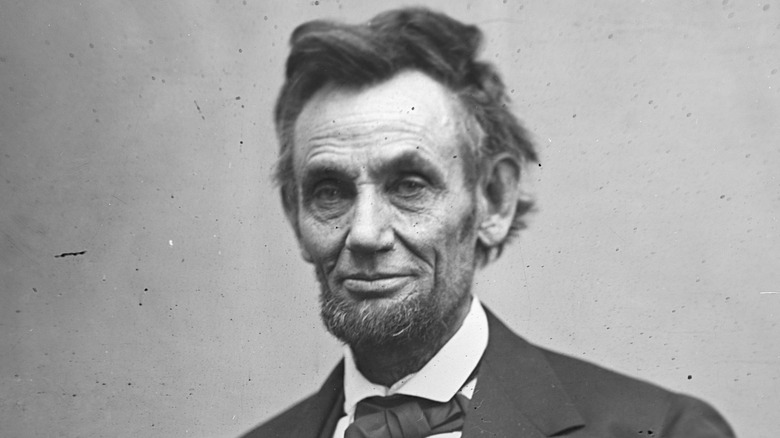

Abraham Lincoln - Best (897)

Ranked first place in every C-SPAN survey, Abraham Lincoln has assumed what the Smithsonian describes as "mythological dimensions." This is partly due to his assassination on April 15, 1865, but the bulk of Lincoln's great legacy comes from his achievements during the American Civil War, which preserved the union and ended enslavement. Lincoln has been described as an "extremely skillful politician" with a "humane, tolerant, and patient" temperament. He was also a pragmatic man who was broadly untethered by ideology. "My policy is to have no policy," he once said, admitting that "I claim not to have controlled events, but confess plainly that events have controlled me" (via Britannica).

According to historian Michael Burlingame (via the Miller Center), Lincoln made "shrewd calculations" and possessed "iron resolve." The president took risks and even defied constitutional law in order to save the union, arguing that it was foolish to "lose the nation and yet preserve the Constitution." Controversy remains over some of Lincoln's emergency measures, namely the suspension of habeas corpus, but few dispute his remarkable success in maintaining the sanctity of the United States, while finally abolishing the institution of enslavement.

Lincoln exceeded 90 points in six of the 10 C-SPAN categories, with his score of 96.5 in "performance within context of times" being his very highest, just 0.1 above the 96.4 awarded to him in the crisis leadership category.

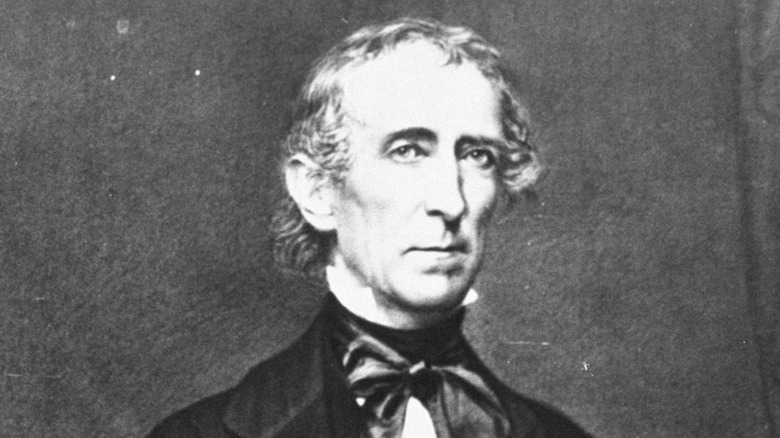

John Tyler - Worst (354)

Inaugurated on March 4, 1841, President William Harrison would be dead just 31 days later on April 4. He was the first president to die in office, and there was no precedent for what happened next. This was decided by Vice President John Tyler, who made full claim to the presidency with a stubbornness that would not bode well with the American people.

"Tyler proved much better at taking over the presidency than at actually being President," argued Professor William Freehling in an article published by the Miller Center. Tyler was incapable of compromise and was preoccupied with states' rights and enslavers, at a time when the United States was becoming increasingly sectarian. Obstinate and out of touch, President Tyler was the wrong man for the wrong time, yet his administration wasn't without some success. A stroke of Tyler's pen led to the statehood of Texas and Florida, while the 1844 Treaty of Wanghia gave the U.S. access to Chinese ports. He also signed the 1841 Pre-Emption Act, which promoted land purchases in the West, and ended disputes in both Florida and along the border with British Canada (via History).

However, despite these accomplishments, Tyler's reputation has not fared well among historians. The C-SPAN survey scored Tyler below 40 points in every category aside from international relations, for which he scored a middling 45.2.

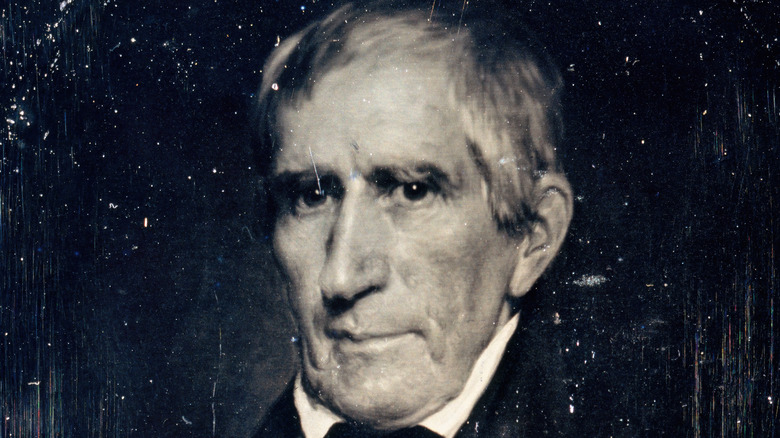

William Henry Harrison - Worst (354)

President for just 31 days, William Harrison does not get a fair shake in the annals of presidential history. C-SPAN's appraisal was low in every category and has only got worse with time. In 2000, he was 37th place; in 2021, 40th. However, Harrison is not a figure without historical insight; it's just that he is relevant to history outside the White House rather than in it.

Historian William Freehling wrote that Harrison employed "innovative campaign techniques" that tailored his image to what the electorate considered admirable, namely spinning the yarn that Harrison was a common man despite his Virginia aristocracy. This has been a common conceit in many subsequent political personas.

Theodore Roosevelt and George W. Bush both adopted cowboy images despite their vast East Coast wealth. Donald Trump managed to have it both ways, flying in his private plane and boasting about his wealth while presenting himself as a fast food-loving everyman and outsider.

Donald Trump - Worst (312)

C-SPAN historians have given a very poor assessment of Donald Trump's presidency, scoring him below 40 in every category apart from public persuasion and economic management, which sit at 43.9 and 42.7, respectively. He scored just 18.7 in moral authority, which is the lowest of any president — lower even than Richard Nixon, who oversaw the notorious Watergate scandal.

The C-SPAN survey placed Trump as the nation's fourth-worst president. However, other assessments are harsher. For example, historian Tim Naftali wrote in The Atlantic that "Donald Trump is the worst president America has ever had," arguing that he was a "serial violator of his oath." Naftali is joined by other critics of Trump, including philosopher Sam Harris, who described Trump as "without question, one of the least honest and most malignantly selfish human beings I have ever come across... he really is missing something that almost every other person on earth has."

The verdict on Trump is far from wholly negative, though. After all, over 74 million people voted for him in 2020 (via NBC), and a Gallup poll conducted during the last days of his presidency had almost one in ten people rate his presidency as "outstanding."

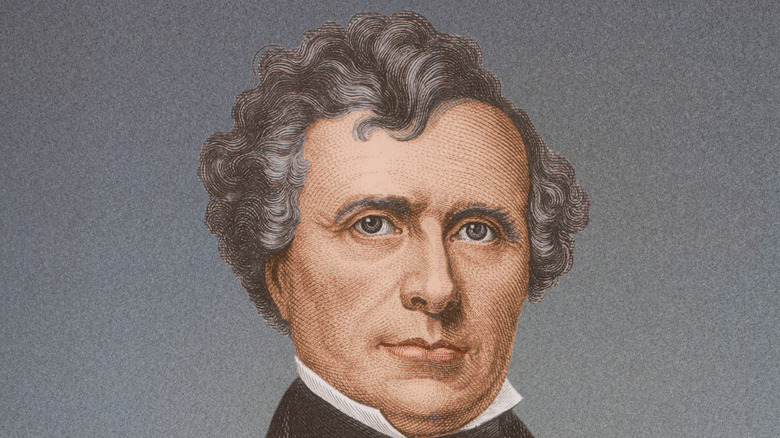

Franklin Pierce - Worst (312)

President of the U.S. from 1853 until 1857, Franklin Pierce has a negative reputation owing to his precursory role in the American Civil War. In an article for the Miller Center, historian Jean H. Baker described Pierce as a "bland [and] affable political lightweight" who won the presidency because of his moderate political stance. Pierce may have been successful in simpler times, but the 14th president was overwhelmed by the issue of enslavement and the Southern states' aggression, and C-SPAN scored him accordingly: Pierce received just 25.0 for crisis leadership, 30.0 for public persuasion, and a paltry 23.0 for "pursued equal justice for all."

However, if C-SPAN had a category for amiability, Pierce may just top the list. "He was probably the most amiable president we ever had,' explained historian Michael Holt (via CBS), "even historians who are hostile to him remark about how pleasant and friendly he was."

Still, likable or not, Pierce was not suited for the office of president. His biggest mistake came in 1854 when he signed the Kansas-Nebraska Act, which allowed voters in those territories to decide the legality of enslavement within their borders. As a result, chaos and violence ensued between abolitionists and proponents of enslavement, hastening the coming civil war that would kill over 600,000 Americans, according to the American Battlefield Trust.

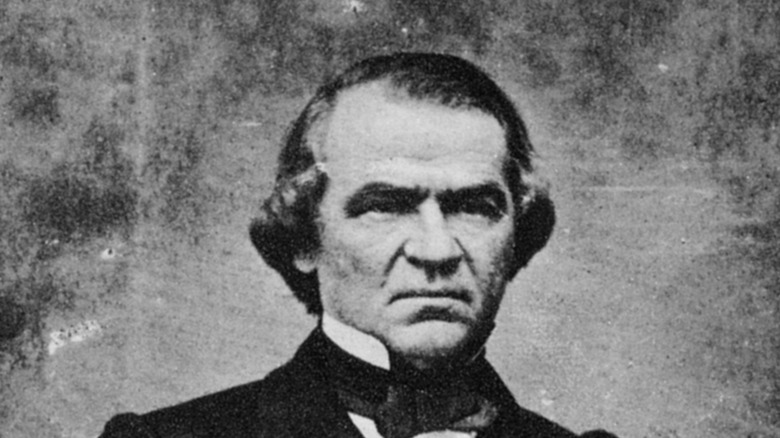

Andrew Johnson - Worst (230)

Andrew Johnson succeeded Abraham Lincoln as U.S. president on April 15, 1865. By most historians' account, Johnson's appointment was a veritable nosedive in character and ability. Professor Elizabeth R. Varon noted (via the Miller Center) the modern perception of Johnson as a "rigid, dictatorial racist" incapable of compromise. Similar views were found in contemporary sources, too: In 1856, the Richmond Whig newspaper described Johnson as "the vilest radical and most unscrupulous demagogue in the Union" (via Biography). However, as president, Johnson actually opposed the radical elements of his party, who favored strict rights for the formerly-enslaved and military rule to enforce them. Johnson vetoed such proposals and chose to refrain from federal impositions on the former Confederate states. He also let state governments decide what to do with freed formerly-enslaved people, who numbered over four million (via CBS).

On February 24, 1868, Johnson became the first president to be impeached. He was accused of violating the Tenure of Office Act, which had been signed in March 1867 to protect Congress' political allies in Johnson's cabinet (via House of Representatives). When Johnson subsequently fired Secretary of War Edwin Stanton, the wheels of impeachment turned but failed in ousting the 17th president.

According to historian Eric Foner (via ColumbiaLearn), Johnson's legacy was highly regarded as recently as the 1950s. However, much has changed since then: Since 2000, C-SPAN has ranked Johnson among the worst presidents, scoring him pitifully low in categories such as crisis leadership, relations with Congress, and "pursued equal justice for all."

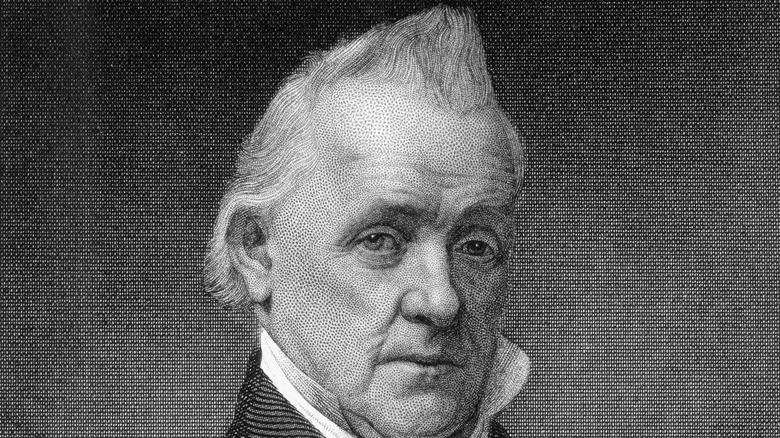

James Buchanan - Worst (227)

According to historian William Cooper (via the Miller Center), James Buchanan was a passive president whose failure to take action on enslavement became a "prime contributing factor" to the American Civil War. Buchanan may have been an esteemed lawyer, but he was a conflict-averse president who used appeasement policies with disastrous results (via PBS).

Buchanan was not just an appeaser, though. Many of his sympathies lay with Southerners, especially on the issue of enslavement. This was evident in the Dred Scott Supreme Court decision, perhaps the defining moment of Buchanan's presidency. When an enslaved person named Dred Scott moved north with his owner to "free" territories in the U.S., he claimed himself to be a free man. The Supreme Court disagreed, dismissing Scott's claim, stating that enslaved people had no citizenry and "no rights which any white man was bound to respect" (via the Miller Center).

According to the Smithsonian, Buchanan was complicit in this decision, and swathes of the country were furious. The president made several concessions by appointing moderates to his cabinet, but the march to war had become irreversible. C-SPAN scored Buchanan a miserable 16.1 in the category of crisis leadership, as well as 19.1 for all categories of moral authority, "vision and setting an agenda," and "performance within context of times."