The Stories Behind Some Of The First Color Photos Ever Taken

When people look at old black-and-white photos, which were the norm in photography until relatively recently, they may find it hard to connect with the people and scenes they captured. After all, everything looks so old-timey. Without color, the subjects can seem very distant. The black-and-white coloring is very much a reminder that they are old and likely dead.

But even though it was difficult, there were pioneering photographers who provided the world with color photos of the past — especially during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. These pioneers, such as Fernand Cuville, Melvyn O'Gorman, and unknown Russian great Sergei Prokudin-Gorskii, all went out to capture the world, whether it was the horrors of war and whatever bright spots in between, the little pleasures of life like spending time with family or enjoying a day at the beach, or cataloging the immense diversity of the Russian empire.

These old color photos bring the past to life, reviving long-dead subjects and turning them into relatable people as if they were still living — almost as if these subjects could have been photographed yesterday. Naturally, behind every photo is a story — a poignant reminder that these were real people with real hopes, dreams, and of course, problems. Here are the stories behind some of the first color photos ever taken.

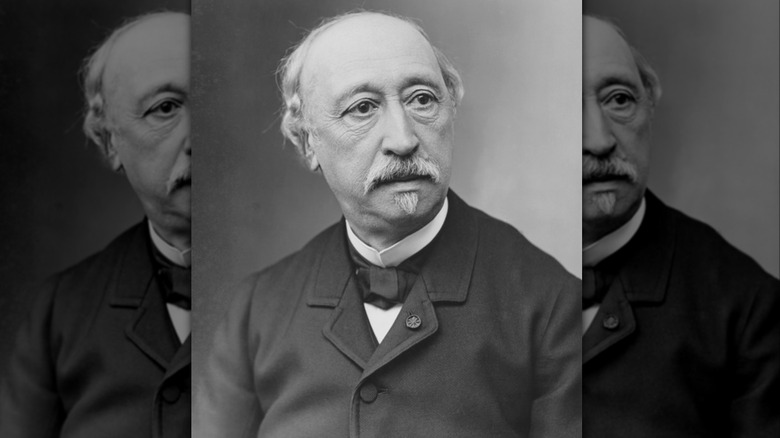

The first color photo ever

The first color photo dates to 1848, although the photo really is nothing special. It was the creation of French physicist Alexandre Edmond Becquerel (above), who experimented with a method to produce a color photo that simply shows a color gradient of purple to white, blue, and eventually, gray.

The problem with this scientific first was that no one actually knew how he did it until very recently, as described by Popular Mechanics. The science behind it is still unclear, but generally, it seems that he scattered silver chloride particles on the plate that was used to show the image. It was how these silver nanoparticles varied in their location and size that determined which wavelengths (and therefore colors) were absorbed or reflected. Thus, the different concentrations of particles absorbed most light except the one color reflected, resulting in a gradient shown in the image.

Thus is the story of the first color photo. Nothing major, other than that most of Becquerel's attempts to create color photos tended to fade away when exposed to light, suggesting that his technique was insufficient to create actual color photos. So it fell to a Scottish polymath to try again almost 15 years later.

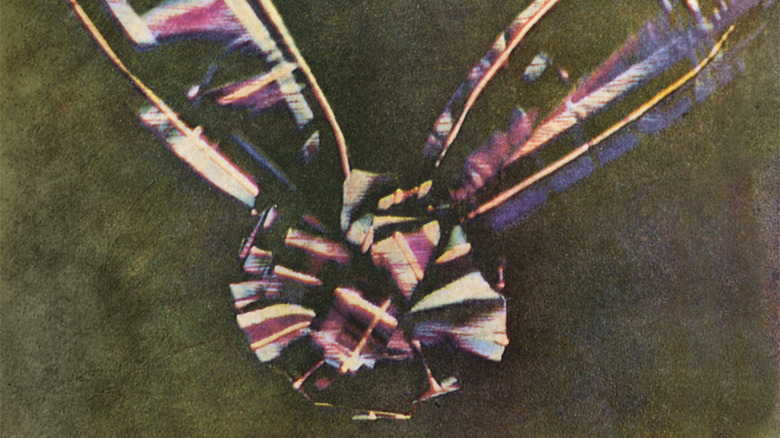

James Clerk Maxwell's tartan ribbon

The honor of creating the first actual color photograph of an everyday object (as opposed to Edmond Becquerel's simple color gradient) goes to Scotsman James Clerk Maxwell. As it happened, according to the Victoria and Albert Museum, Maxwell did not care about photography in itself. He was more interested in the physics of light and color. But his desire to prove that any color could be generated by mixing blue, red, and green was enough to get him into the field. He teamed up with photographer Thomas Sutton to prove his point and, along the way, ended up pioneering the three-color method.

Simply put, this involved creating the standard black-and-white negatives, but through a set of red, green, and blue filters. When they were projected superimposed on one another, they produced a near-true color picture. Maxwell's chosen subject, in keeping with his Scottish heritage, was a tartan ribbon.

The funny thing about Maxwell's experiment was that he had discovered the three-color process by accident. He had never intended to create color photos. Yet thanks to his curiosity, he has the bragging rights to the first true color photo. His negatives eventually became the basis for another process of producing color photography in the 1930s by one Dr. Douglas A. Spencer, who used Maxwell's original negatives to create a second version of the image using the Vivex process.

Mark Twain in color

American writer and satirist Samuel Clemens, better known by his pen name Mark Twain, was photographed plenty of times in the 19th century — usually in black and white. But by the end of his life, during the closing years of the first decade of the 20th century, his photo was taken at least twice in color using the autochrome process, patented in 1904 in France. The photo belongs to the Phillips Collection Museum in Washington, D.C. It shows Twain reading a book while relaxing on his bed with a pipe in his left hand.

Now, it is unclear what the context of the photo is. Although dated to 1911, Twain died in April 1910. Thus, the color photo of him cannot have been taken in 1911 and must be from earlier. The photographer's name, Alvin Langdon Coburn, also provides another clue as to the date, considering that he was Twain's guest on at least one occasion.

The photographer visited Twain at his home in Connecticut in 1908 and snapped a few photos of the famous writer. Whether the color photo was one of them is an open question, but it seems likely that it could have been considering Twain's age in the photo. Either way, it is a fascinating memento of one of America's greatest writers, who is truly brought to life for modern eyes as he looked in real time, rather than through the distant lens of a black-and-white photo.

Mervyn O'Gorman's Christina

The beauty of early color photography was that it often captured simple, everyday pleasures of life, whether family portraits, children playing, people taking a break from work, and more. Among the most famous color photos is Irish photographer Mervyn O'Gorman's 1913 collection focusing on one "Christina."

"Christina," a blonde Irish girl who appears in a set of photographs ranging from a picnic on the beach with her mother and sister, to walking along the shoreline and enjoying a garden, went viral on social media because the photos looked like they could have been taken yesterday. The Spanish newspaper El Pais even dubbed her a "20th century pin-up girl." But no one knew the story behind them or who she was.

With little information, it was believed that the girl was Mervyn O'Gorman's daughter. But he did not have any children, so that possibility was discarded. In 2015, however, a man gave O'Gorman's original slides to the Science and Media Museum, including O'Gorman's captions and notes. It turned out that not only was the girl's name "Christina." O'Gorman and Christina's parents were neighbors, living a mere two minutes away from each other. For whatever reason, the photographer accompanied Christina's mother Mary and sister Anne to the beach and snapped the beautiful photos, that have posthumously made Christina a social media star.

Sergei Prokudin Gorskii's Greeks of the Caucasus

A giant of early color photography, Sergei Prokudin-Gorski is relatively unknown in the West, given that he photographed in the service of the Russian empire and Czar Nicholas II. His stunning photos showcase various facets of the sprawling empire, including its many diverse ethnic and religious groups.

Prokudin-Gorskii's photos show Russia's ethnic groups before the various purges and genocides of the communist era. Among the standouts — albeit not one of his most famous — is a photo of Greek women harvesting tea (via Library of Congress). But these were not Greeks from Greece. They were part of an ancient Greek minority living on the eastern shore of the Black Sea and in the Caucasus mountains, in what is today Georgia.

Looking at the women in the picture, it is sad knowing that a nasty fate likely befell many of their fellow Greeks, as their lives were thrown into tumult first by the Bolshevik Revolution of 1917, and then the Russian Civil War. Later, under Joseph Stalin and Nikolai Yezhov, Greeks were targeted alongside numerous other ethnic groups in the Great Purge of 1936–1938 for allegedly sympathizing with Germany, Britain, and Japan, per the Greek City Times. Their fate was often either execution at the hands of NKVD death squads, or deportation to the Siberian gulags.

The portrait of Alim Khan

Among Sergei Prokudin-Gorskii's more famous photos is a portrait of Mohammad Alim Khan (via Library of Congress), the Emir of Bukhara (today a city in Uzbekistan). The photo was taken in 1911, when the emir was around 21 years old, just after he had taken charge of the emirate, which was a Russian subject.

In his portrait, the emir appeared dressed in his finery, but he, like many other monarchs of the era, was facing the final years of his rule. The problems began in 1916, when a revolt across the emirate resisting the emir's attempt to conscript laborers threw the region into chaos, according to Cambridge historian Malika Zehni (via Peripheral Histories). When the Bolsheviks seized power in 1917, they already had plenty of sympathizers in Central Asia to help them out.

When the Bolsheviks seized power, the emir declared independence, hoping to keep his people (and himself) from falling victim to the bloodthirsty revolutionaries. But in 1920, the Red Army invaded the emirate, carpet-bombed the city, and destroyed it. The terrified emir, who described the terrifying scene of soviet pilots "[throwing] bombs from aeroplanes" in the middle of the night, fled for Afghanistan. He died in Kabul in 1944, never returning to his beloved city of birth. Some of his descendants, however, live in the United States, according to an interview with the emir's granddaughter and great-granddaughter (via The Mag). So despite the emirate's tragic end, the dynasty continues.

Jewish teacher with pupils in Samarkand

Rounding out the representatives of the Prokudin-Gorskii collection is a photo capturing the last years of the golden era of the Bukharic Jewish community of Central Asia. The photo shows a teacher surrounded by pupils, as they study a religious text on the side of the street in Samarkand.

The Bukharic Jews form a unique branch of Judaism. They predate the diaspora, most likely being descendants of Jews who ended up in Central Asia following the Babylonian captivity of 586 BC. They settled in what is today the ex-Soviet republics of Central Asia, particularly in the cities of Samarkand, Tashkent, and Bukhara in Uzbekistan. They spoke Persian and were generally traders and merchants.

The late Russian imperial era saw Bukharic Jews grow immensely wealthy and emerge from their isolation relative to the rest of the diaspora. Community members traveled west to dialogue with their European counterparts and established charitable organizations and schools in the Ottoman Empire. As it turned out, over two millennia of separation had resulted in Bukharan Jews having different rules on matters such as kosher and marriage/divorce.

Ultimately, the Bukharic golden age that Prokudin-Gorskii captured only a very small portion of was cut short in 1920, when the Red Army invaded the Emirate of Bukhara and annexed it, isolating the community once again. It would only be through contact with Soviet Jews after World War II that the community would find its place in the world once again.

Little French girl playing with doll in Reims

One poignant photo dates back to Western Europe during the bloody years of World War I — specifically 1917, during the Franco-British offensive near the Marne. The photo in question, taken in the French city of Reims by photographer Fernand Cuville, shows a little girl sitting on the sidewalk playing with her doll, next to a soldier's backpack and two rifles.

The exact story behind the photo is unclear, but given its date, it was likely taken when Entente forces were fighting the bloody Battle of the Aisne, which saw German forces shell the city, leaving much of it destroyed. A second photo, also by Cuville from the same collection taken the same year, shows the city's famous medieval cathedral completely in ruins (via the Australian War Memorial)

The photo appears to capture an incredible juxtaposition: that of the innocent girl playing with her doll on one hand, who ideally should never have to experience the horrors of a world war, and the reality of conflict on the other, as seen by the soldiers' equipment. Did Cuville intend to capture the juxtaposition, or was he simply looking to find some joy amid the ruins and death he was witnessing? Either way, he certainly got both. The photo is both a reminder of the difficulties of war for society's most vulnerable, yet also captures the joys of childhood in spite of the carnage around the girl.

Hustle and bustle of Mulberry Street, NYC, 1900

This photo is one of the most iconic of early 20th century New York. It shows the hustle and bustle of everyday life on Mulberry Street — the heart of Manhattan's old Little Italy neighborhood.

Mulberry Street and Little Italy were generally considered a slum, as Danish photographer Jacob Riis noted in his famous book "How the Other Half Lives." In fact, Riis had little good to say about Italian immigrants or their neighborhood, but he did enjoy the colorful traditional outfits of Italian women, who he thought brought color to an otherwise drab city. Nevertheless, despite the slum conditions, Little Italy was full of people looking to make something more of themselves than they had back at home.

Nevertheless, there was another side to the windowless, cramped tenement neighborhood, and that is portrayed in the photo. In 1896, despite the hardships, Little Italy was a center of activity, as people from all walks of life attempted to "make it." Mulberry Street and the surrounding neighborhood were teeming not just with low-status manual laborers, artisans, and rag-pickers, but also with doctors, lawyers, clergy, and bankers — all who provided services to keep the community together. So even though life was not easy in the hardscrabble New York ethnic neighborhoods, there is no doubt, judging from both the photo and the NYT's description, that a lot of people certainly forged their own American dream.

Interior of J.P. Morgan's Library

This photo (via Library of Congress) shows the beautiful interior of the private library of one of America's richest men — financier John Pierpont Morgan. His is a name Americans generally know well due to his outsized influence during the Gilded Age and Progressive Era, as well as the fact that his name adorns one of America's megabanks — JP Morgan-Chase. But apart from his financial life, Morgan was also an avid collector of everything from antique manuscripts and books, to Mesopotamian and Classical antiquities.

Morgan had not intended to build the Morgan Library. According to The New York Times, he came upon the idea after he had collected so much stuff that his mansion was running out of room to store everything. So the banking tycoon opted for the great American tradition of dumping whatever doesn't fit in the house in his basement. As his son-in-law noted, it was impossible to find anything, as every single chair, table, and inch of the floor had been completely filled.

By 1900, Morgan decided to move all his stuff to a more dignified location. He purchased the neighboring property at 36th and Madison — which belonged to fellow tycoon and industrialist Henry Frick — and hired an architect to turn the property into a Renaissance-revival palazzo made of marble. The result was a building described simultaneously as "very rich and very cold." A strange description, but judging from the photos, it certainly looks like Morgan gave his antiquities a home worthy of their stature.