What The Oldest Known Photographs Tell Us About History

Photographs are a remarkable window into history. They freeze moments in time, holding things as mighty as the sun or as finely detailed as a plant's leaf in place for examination. Thanks to photography, we can look at people who have been gone for centuries. The moon stands still. John Quincy Adams stares into our eyes. We're frozen before a tornado as it touches down onto the Kansas landscape. We see the careful details of a botanical specimen, placed there by botanist Anna Atkins and memorialized in a bright blue cyanotype. Photography, unlike any other art form, has the ability to bring us right into a historic moment.

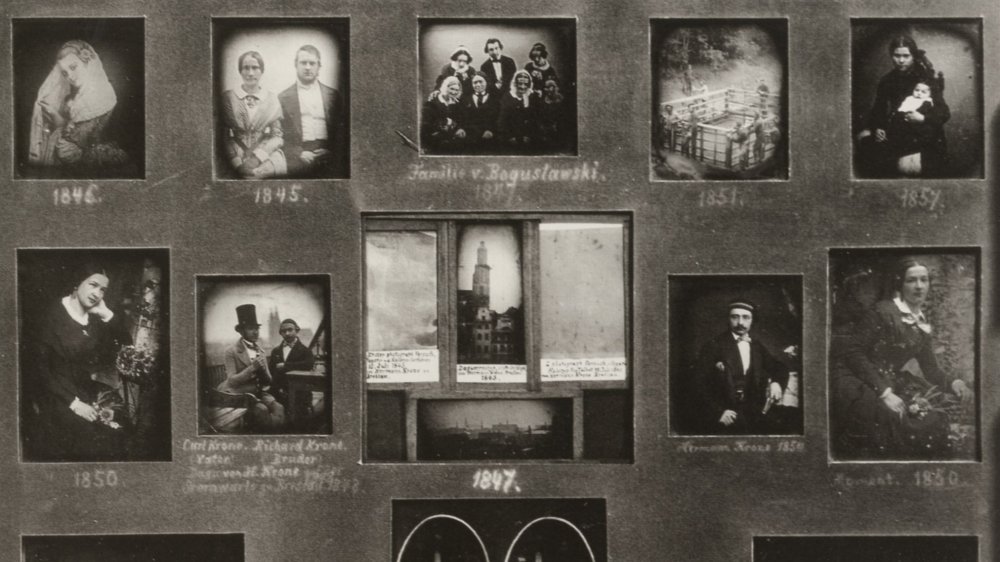

Even the earliest photographs hold a lot of history. Yes, the very beginnings of this profession produced a lot of pictures of rooftops and other things that would hold still for the hours-long exposure process, but even those pictures represent a huge leap forward. As early adopters like Louis Daguerre, whom the Metropolitan Museum of Art says is now a giant of the field, refined the steps necessary to take a picture, photography spread out into the world like never before. It soon became an important tool to document people, cities, scientific advancements, and more. Even a seemingly boring picture of a bit of ribbon, taken in 1861, proves to be exciting once you dig into the narrative.

The first known photograph was the result of a scientific breakthrough

The road to the first-ever photograph was not an easy one. For centuries, people had known about camera obscuras, My Modern Met says. These devices, which could take up entire rooms or tents, relied on a small pinhole. When light hit a nearby object and traveled through the pinhole, an upside-down image of the outside world was produced on the opposite wall. Cool as it was, the process demanded a lot of time and space. How could a camera obscura be scaled down to produce an easy, portable process?

It wouldn't happen until 1827 when French inventor Joseph Nicéphore Niépce made the first known photograph in human history. According to The International Printing Museum, Niépce created it through a laborious process that had taken him years to refine. For the successful photo, he took bitumen, a light-sensitive chemical, dissolved it in lavender oil, then applied the mixture to a polished sheet of pewter. He then put the plate into a small camera obscura looking out the window of his workshop. After many days, Niépce withdrew the plate and saw an exact, though fuzzy, replica of the rooftops and trees outside.

The heliograph, as Niépce called it, was fascinating but not ready for commercial use, per the Harry Ransom Center. It wasn't until Louis Daguerre, a fellow Frenchman, created the daguerreotype process that photography became more available for public use.

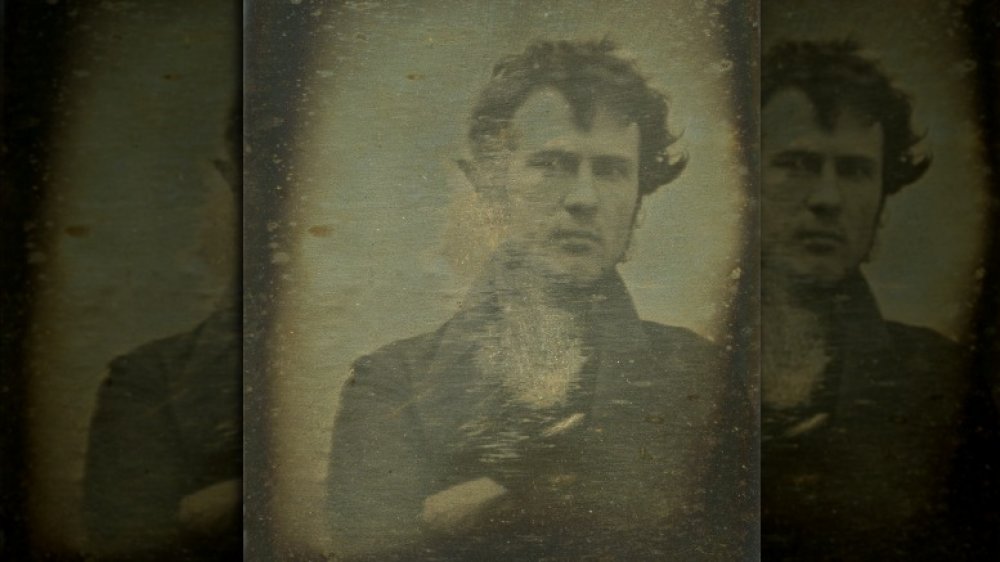

An 1839 photo shows humans have always admired themselves

Humans love to look at one another and themselves. It's a natural reaction and, as long as you don't get too enamored of your own reflection, nothing to be ashamed of. Consider the long history of the self-portrait, which artists have been creating for centuries, The Guardian reports. Even the photographic selfie, which has been the subject of many hot takes over the past few years, has a longer history than many know.

According to The Public Domain Review, the honor of the first selfie almost certainly goes to a man named Robert Cornelius. In 1839, Cornelius, an amateur chemist and budding photographer, set up his camera in his family's Philadelphia store. Because exposure times took much longer to fully capture the light needed for a photograph, Cornelius was able to remove the lens cap, run in front of the camera, sit for a minute, and then quickly cover the lens again.

An 1838 photo captured the Paris of Victor Hugo

The Paris of 1838 was a tumultuous place, roiled by social unrest, epidemics, and a quickly growing population. During the period between the Revolution of 1830 and the Revolution of 1848, per the Journal of Social History, the city saw at least three different rounds of intense violence.

It wasn't all bad, at least not if you were a supporter of King Louis-Phillipe, the bourgeois "citizen king," according to Brown University. Meanwhile, crops were producing great supplies of food and many people flocked to the capital city, pushing the bounds of Paris to its limits. If you were a lower-class citizen or a supporter of Napoleon Bonaparte, the reign of Louis-Phillipe grew tiresome, even dangerous, as the king failed to respond to the needs of the citizenry.

This was the world photographed by Louis Daguerre in 1839, though you wouldn't know it by the picture he took. As reported by My Modern Met, this particular daguerreotype is of a large boulevard in Paris, looking south towards the Boulevard du Temple. But, the street is nearly empty. That's because many folks were simply moving too quickly to make it onto the image during the 10-minute exposure. Only two figures, of a shoe shiner and customer, are visible on the corner. As far as anyone knows, this is the first photograph of Paris and the first to capture the image of living humans.

A photographic hoax was part of an 1840 feud between inventors

By the 1830s, the world of photography was full of brilliant and contentious people. Sometimes, they could play together nicely. Joseph Nicéphore Niépce and his son, Isidore, teamed up with Louis Daguerre in late 1829, The International Printing Museum says. When the elder Niépce passed away, Daguerre continued to nurture their growing business, eventually producing the daguerreotype method. According to the Library of Congress, this was the first publicly available photography.

Louis Daguerre didn't get famous without stepping on a few toes. One such set belonged to Hippolyte Bayard, per Modern Fiction Studies. Bayard was another French citizen who had gotten involved in photography. Yet, at least to Bayard, it seemed as if Daguerre was taking the acclaim for himself and leaving little for his peers.

By 1840, Bayard was so sore about his lost recognition that he staged the first faked photograph, ArtStor reports. In it, Bayard poses as a drowned corpse propped up next to a straw hat. On the reverse is a note signed by "H.B." It contains a complaint that, while he's been honored for his work, Bayard has not received any money for his efforts. "The government, which has supported M. Daguerre more than is necessary, declared itself unable to do anything for M. Bayard, and the unhappy man threw himself into the water in despair." Bayard actually lived until 1887, the Getty Museum reports.

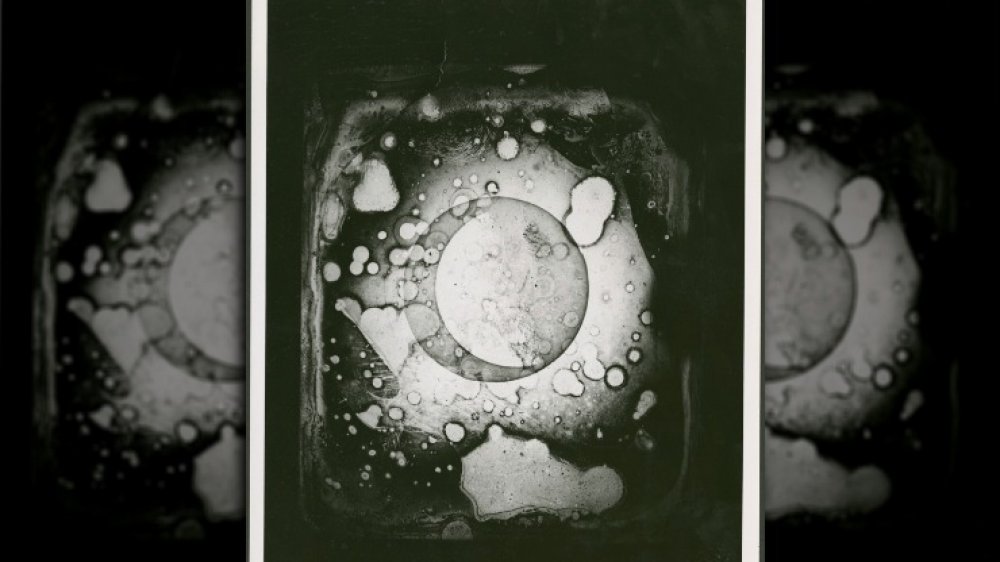

Scientists adapted the technology to learn about the heavens

As photography gained momentum, scientists realized that it could be an important tool. Someone could take an accurate photograph of a scientific phenomenon and save it for study at a later time. For astronomers, who could spend hours hunched over telescope eyepieces and even longer hours trying to reproduce what they had seen, photography was a huge advancement. However, they did have to start fairly close to home. The first surviving photograph of the moon, which is a mere 238,855 miles from Earth, according to NASA, was taken in 1840.

As per Lights in the Dark, this photo, which is also very likely the first photograph taken of anything astronomical, was made by John W. Draper. A scientist, philosopher, and university professor, Draper captured the image of the moon by improving on Louis Daguerre's method of exposing a metal plate coated with light-sensitive chemicals. The resulting image, now heavily damaged, was at the time Draper's best effort, which he proudly displayed at the New York Lyceum.

Five years later, Slate claims, French scientists Hippolyte Fizeau and Léon Foucault used a similar daguerreotype process to take a picture of the sun. They faced a tougher time, as the bright sun demanded that they reduce the exposure as much as possible to pick out features like sunspots on the surface of our nearest star.

Color photography took serious work and science

In the early days of photography, all processes produced black and white images. It was enough work to simply capture the saturation of light on different surfaces without fussing over how cameras would reproduce color. Still, people wanted to see some pigmentation, leading to a healthy little industry of hand-colored photographs, Cornell University says.

But what about actual color photography? That development came about earlier than you may think, but it took many decades before it became practical. According to Open Culture, the very first color photograph was made in 1861. Physicist James Clerk Maxwell, who took the photo, drew upon earlier experiments where color had almost immediately faded from the image. His three-color method, where an object was photographed three times through red, blue, and yellow filters, was so stable that we can still see the colors today. The resulting photo, of a plaid ribbon, is striking.

So, why didn't color photography take off? Maxwell's method didn't always produce accurate colors. It was also a laborious process that didn't work well for living subjects, who needed to do tiresome things like blink, sneeze, or breathe. According to the Science and Media Museum, color photography didn't get popular until subtractive color processes were developed in the 20th century. New color films and cameras using these ideas debuted in the 1920s and 1930s, finally making color photography more accessible.

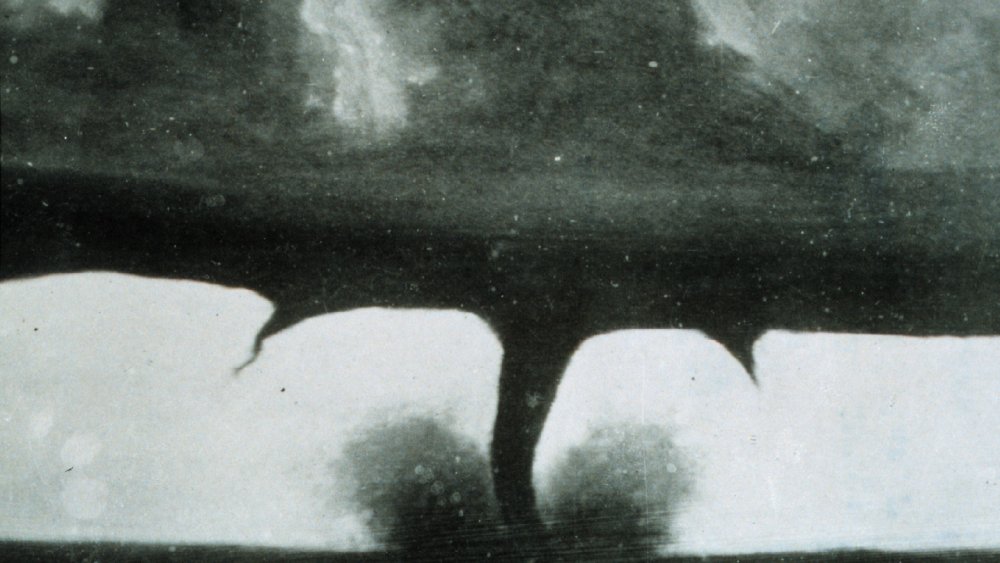

The oldest tornado photo adds to the history of storm chasers

Storm chasers have been an occasional staple of television for years now. It's easy to understand why, with the dramatic images of destructive weather, taken in dangerous conditions, which you can peruse from the safety of your couch. How Stuff Works says that the first storm chaser was arguably none other than famed naturalist John Muir. Though he's better known today for helping to establish the U.S. National Parks system, in 1874, he risked his life to climb to the top of Douglas spruce during a wind storm to experience what the treetops did in such intense conditions.

Nearly 10 years later, storm chasers were using the emerging technology of photography to document their exploits. As per WeatherNation, the first known photo of a tornado was taken on April 26, 1884 in Anderson County, Kansas. As the funnel touched down nearby, farmer and amateur photographer A.A. Adams risked precious minutes to assemble his camera. Another photo taken mere months later in South Dakota, shown above, overshadowed Adams' work, per the Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society. For most researchers, however, it's clear that the tornado of Anderson County was the first to make it onto film.

Photography helped make a holy site more accessible

One of the greatest promises of photography is its ability to connect far-flung people and places, regardless of time or geography. Viewers could safely get a close view of the sun, look into the eyes of the sixth U.S. President, or see the streets of Paris, though they might be oceans and continents away from the real place. By the 1880s, they could also get a then-rare glimpse of one of the holiest sites in the world.

In 1881, Muhammad Sadiq Bey, an Egyptian photographer, was the first to make photographs of Mecca, according to Arab News. This holy city, in what is now Saudi Arabia, and its monuments are a central focus of Islam, one of the world's largest religions. For the faithful, completing at least one hajj, or pilgrimage to Mecca is the hope of many Muslims. Ultimately, per Khan Academy, pilgrims who make it there will gather around the Kaaba, a shrine that contains the holy Black Stone, reportedly given to the patriarch Ibrahim by the angel Gabriel.

Sadiq Bey's images of the Kaaba and other sights around Mecca were both carefully staged and intimately experienced, The Indigenous Lens says. For viewers, some of whom would never get to see the city at the center of widespread religious belief, it was a new chance to connect with a place and culture.

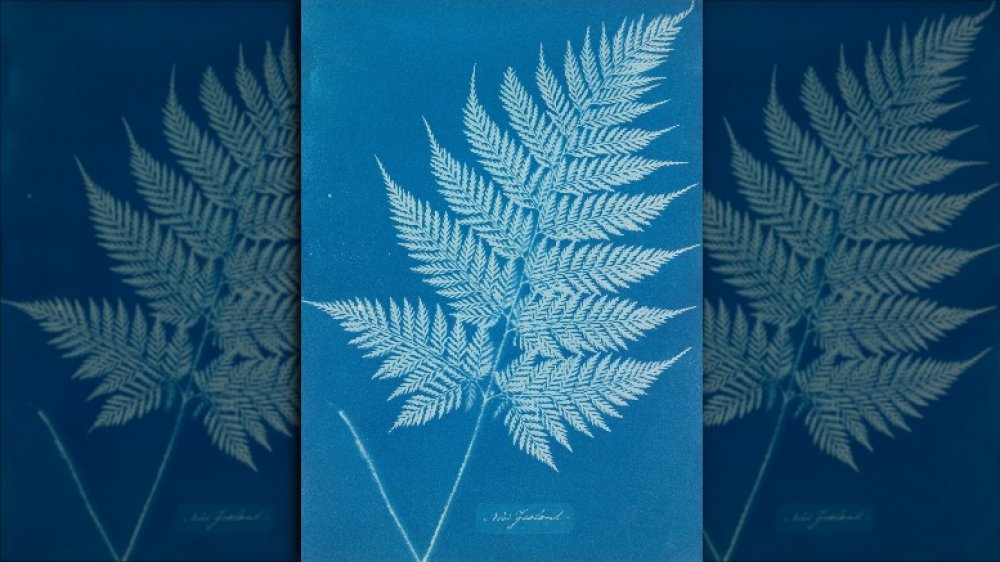

Photos of plant life display women's role in science

The history seen through photographs is often interpreted as the history of men. Rightfully or not, men are featured on both sides of the lens. Yet, dig a little deeper, and you'll see that women have been a part of photography since its earliest days.

Anna Atkins is very likely the first woman to ever take a photograph. By the 1840s, when her interest in photography had taken root, she was already a respected botanist studying the plant life of her native Britain, per the Museum of Modern Art.

Atkins used a very specific kind of photography to capture the details of different plant specimens. According to Britannica, she employed the cyanotype process invented by astronomer Sir John Herschel. Using iron salts, Herschel had invented a process where paper would be coated with a light-sensitive substance. When Atkins overlaid plant life onto the paper, exposed it to the sun, and then washed the paper in a water bath, the delicate details of her findings were imprinted onto the bright blue result.

Atkins undoubtedly realized that the images were much more detailed and easier to produce than engravings, which she had done for her scientist father's earlier work on seashells. According to the National History Museum, she's widely acknowledged as the first scientist to publish a book with photographs as illustrations.

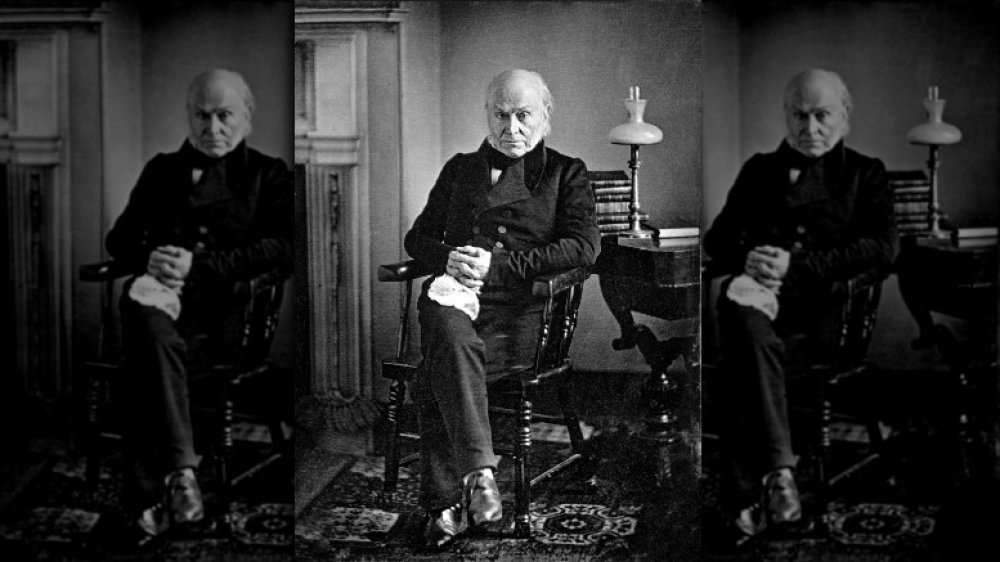

Presidential photos document the early history of the United States

Portraits have been a deeply beloved artform for thousands of years, the Tate Museum claims. Since Ancient Egypt, people, and especially people who were considered to be outstanding amongst their fellows, had their images carved, woven, painted, stamped, and impressed on nearly every surface artists could alter. By the middle of the 19th century, photos offered a chance to capture the detailed image of a subject with far less effort and anxiety than a standard oil portrait.

That's why we find John Quincy Adams on a daguerreotype, taken in 1843. According to The Atlantic, he is the first U.S. President whose photo has survived, though he was 14 years out of office when the image was made. There are actually two candidates for the first photo, making it unclear which was properly "first." Adams himself seemed pretty nonplussed by the whole process, even saying that his photos were "hideous." In his diary, Adams seemed more interested in writing about his travels and getting a pebble briefly stuck in his eye.

The first-ever photo of a president, sitting or retired, was taken of William Henry Harrison shortly after his inauguration in 1841, per The New York Times. Harrison is best known as the president who died a mere 32 days into his term, dying of what Britannica claims was pneumonia, from a cold contracted at his own inauguration. In a tantalizing twist, that photo has been lost.

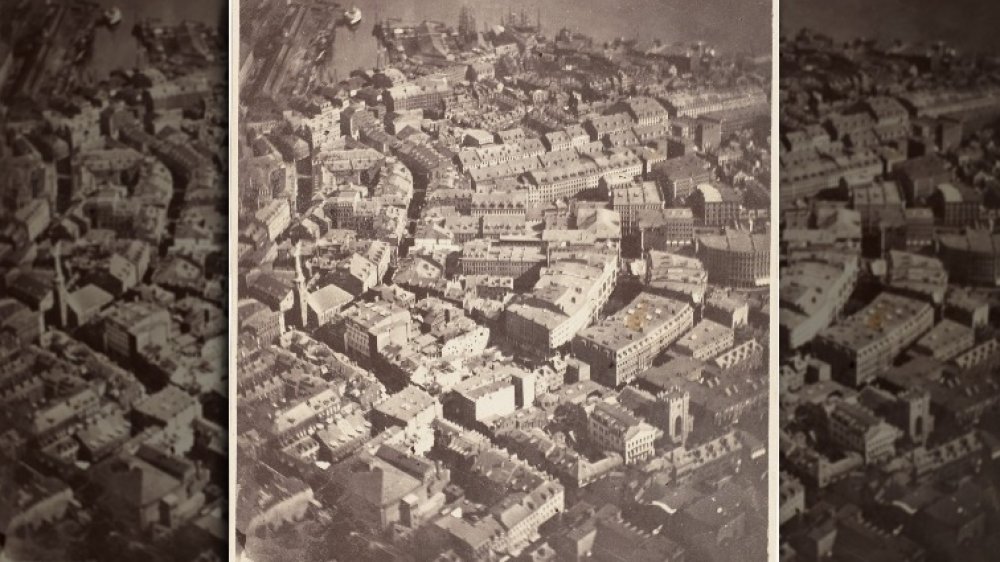

An aerial photo shows pre-Civil War Boston

By the middle of the 19th century, aerial photography was able to take what was probably the most photographed city in the world and make it extraordinary to its inhabitants. Nadar, a French photographer, took the first aerial photos ever when he photographed Paris from in 1858, per the New Yorker. Despite his derring-do and the gigantic hot air balloon that got him aloft, the photos themselves are lost. It's a shame, since, according to Art in Society, Nadar was so in awe of the views from around 1,600 feet up that he said it was nothing short of "an invitation to the lens."

Two years later, the Metropolitan Museum of Art reports, James Wallace Black took the first surviving aerial photographs. The images show Boston just before the American Civil War erupted. Black went up in the "Queen of the Air," a hot air balloon owned by his associate, Samuel King. In 1863, writer and statesman Oliver Wendell Holmes waxed poetic about the image, calling it a "remarkable success."

By the end of the Civil War, both sides of the conflict experimented with hot air balloons, though the Union forces were more organized and successful. According to the American Battlefield Trust, Union balloons deployed during the Seven Days Campaign in 1862 could observe Richmond, Virginia from seven miles away. Oddly, no one took photographs from these military balloons.

The oldest digital photograph was part of the computer revolution

The digital revolution of the 20th century is now firmly entrenched in our lives. You are very likely reading this from a screen, be it on your computer, phone, or tablet. Where would we be without the agglomeration of pixels to simultaneously inform and distract us? And what does this baby have to do with it all?

First, we have to briefly go back to the 19th century. According to the Science and Media Museum, scientist Shelford Bidwell was the first to imagine sending a picture as an electronic signal, all the way back in 1880. Bidwell's "telephotography" actually worked, as he demonstrated when he transmitted simple pictures of a butterfly, then a horse, over the wires. Alas, his work didn't spark much interest, and so the idea of digital imagery sat quiet for decades.

Scientists in the 20th century experimented with Bidwell's early work, but it wasn't until 1957 that Russell Kirsch created the first digital image. The young engineer scanned a photo of his three-month-old son, Walden, and successfully transferred it onto an early computer, the Washington Post reported. The photo, which measured a square 176 pixels, was the first digital image.

As much of a fantastic advance as this image was, it wasn't the first photo taken by a digital camera. That honor really goes to Steve Sasson, who invented the first self-contained digital camera in 1975, per The New York Times.