Fake Archaeological Finds That Nearly Changed History

At some point in your childhood, you probably wanted to be an archaeologist. Depending on your age, it probably had a lot to do with either the Indiana Jones movies or Tomb Raider. Either way, nothing seemed cooler than digging out old bones, relics, or religious items, and then forcing those snobby history book editors to make revised editions. Real-life archaeology might not involve magical arks that melt people's flesh off, but it's still insanely cool: When archaeologists uncover ancient plumbing, statues, or fossils, they reveal the history of humanity, plug up the holes, and sometimes prove old theories wrong.

Every once in a while, though, a prankster gets in the mix and tries to cash in on some fake discovery. These turkeys always get found out sooner or later, but not without breaking some hearts on the way. Here are some of the biggest archaeological hoaxes that would have changed history.

The 'Michigan relics' were baloney

The world might never know the identities of the first Eurasian crew to plant their anchor on North American shores. It definitely wasn't that ruthless tyrant Christopher Columbus, considering the Vikings beat him by a couple centuries. But what if another crew of ancient tourists predated the Vikings?

Well, back in the 1890s, a bunch of strange relics turned up in Michigan. According to Mark Ashurst-McGee, these clay, copper, and slate "artifacts" got people buzzing because they featured artwork depicting key biblical scenes, like Noah's ark and the life of Jesus. That wouldn't be unusual, except the relics appeared to date to a period hundreds of years before the Vikings or Columbus sailed any blue oceans. If these Michigan relics were real, it would've meant that in ancient times, a brave crew of early Christians from the Middle East had sailed to North America way before it was cool, hiked halfway across the continent, and settled in the most insanely cold region of the United States. This particular narrative happens to appear in the Book of Mormon, so members of the Latter-day Saints Church had high hopes.

The hubbub didn't last long. Once actual archaeologists came along, they quickly pointed out that the artifacts were totally bogus. That hasn't stopped some people from believing in the Michigan relics, though, to the point that Mormon organizations still have to (wearily) field questions about them.

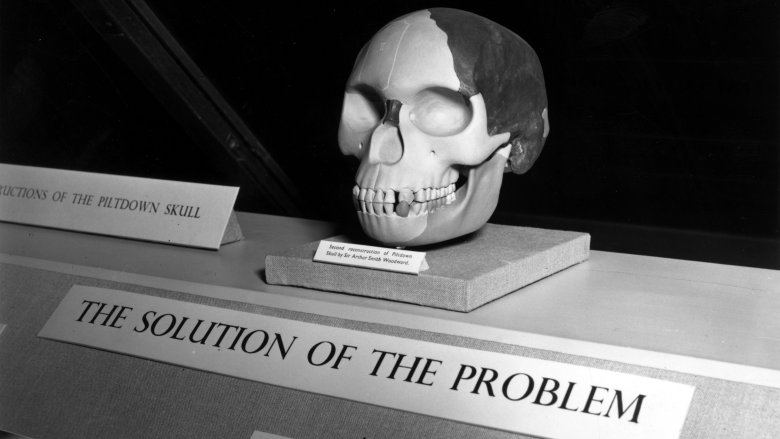

Sorry, humanity's 'missing link' didn't come from England

No country "owns" history, but several have sure gotten possessive over it. While it took the ever-egotistical human race a long time to recover from the whole "people descended from apes" thing, the debate only got more contentious in 1907, according to Science Magazine, when a jawbone was found in Germany belonging to Homo heidelbergensis, a primate that was likely the common ancestor to both Homo sapiens and the now-extinct Neanderthals. Not surprisingly, U.K. naturalists got crazy jealous, and a few years later, a rather convenient discovery happened: Charles Dawson dug up a complete skull, the real missing link in human evolution, right in the quaint little British village of Piltdown. This revelation made England the birthplace of humanity. Take that, Germany!

The Piltdown Man skull paired a human-sized brain with an apelike jaw and teeth. A little too perfect? Yep. In all likelihood, it seems Charles Dawson fused a regular human skull to an orangutan jaw, gussied it up, and called it a day. The scientific establishment didn't even realize it had been punked until decades later, in 1953, when a new technique called fluorine dating proved the whole thing was a fraud. By this time, Dawson was dead, but his postmortem legacy definitely took a hit.

James, brother of Jesus

Putting religion aside, was Jesus Christ a real guy? Most scholars will tell you "probably so," but the evidence isn't as concrete as many believers would like. That's why it was a big deal back in 2001, according to Time, when a mysterious relic collector named Oded Golan told the world he'd found an ancient stone ossuary — bone box — carved with an Aramaic inscription reading "James, son of Joseph, brother of Jesus."

Sure enough, the world lit up like a Christmas tree. The box went on tour in Canada. People stared at it, prayed on it, and theorized about it. If the James Ossuary was real, it was long-awaited proof of the historical Jesus and proof that the apostle James was Christ's brother. As all this craziness was going on, the detectives of the Israel Antiquities Authority worked behind the scenes to figure out that while the ossuary itself was genuine, the part of the inscription that said "brother of Jesus" was a forgery. Having a man named Joseph with a son named James doesn't mean much.

Oded Golan was put on trial for forgery, but he was cleared after seven years, according to LiveScience.

'God's Hand' at work in Japan

Sometimes, archaeological hoaxes hurt real people and even whole economies. In the 1990s, according to the New York Times, a Japanese man named Shinichi Fujimura gained the nickname "God's hand" when he went digging in the town of Tsukidate and found a bunch of intricate stone tools allegedly dating back over a half-million years. This revelation turned Japan into one of the most important sites in early human history, and as Fujimura continued unearthing a shocking array of evidence for an advanced early Japanese society, the town of Tsukidate gained a popular reputation as the "Cradle of Japanese Man." Tourists came flocking. Cavemen cartoons became mascots. A street was named Original Man Way, and runners came flocking once a year for the Original Man Marathon.

Then, it all came crashing down. In the year 2000, the BBC reported that Fujimura had been filmed burying his "great discoveries" underground right before digging them up. Evidently, God's Hand wasn't so godly. Since the footage spoke for itself, Fujimura couldn't make any real excuses, so he apologized for the now-dozens of fakes he'd planted. Sadly, all this tomfoolery destroyed the town of Tsukidate's newfound fame as a Stone Age treasure trove.

When giants didn't walk the Earth

Giant human beings are real, but they don't say silly things like "fee-fi-fo-fum," and they're generally just normal folks who happen to be 7 or 8 feet tall. However, lots of mythologies around the world have spoken of "giants" who stand anywhere from 12 to 400 feet off the ground, and some Bible fundamentalists take those early accounts of giants quite literally. Back in 1867, according to History, this literalist attitude so perplexed George Hull, an atheist cigar maker, that he spent $3,000 of his own money on the hoax of the century.

Since 3-D printers didn't exist back then, Hull ordered that a giant 10-foot-tall human sculpture be carved of solid gypsum. He then shipped it to his distant cousin's farm in Cardiff, New York, and buried it. One year later, the "Cardiff Giant" was dug up, and people went crazy. Everyone figured it was a real, ancient giant, whose rocky form was due to petrification from the nearby swamp. P.T. Barnum even tried to buy it. Meanwhile, George Hull was busy puffing on one of his cigars, delighting in the mischief. By the time the experts had sussed him out, he'd already banked $20,000 in admission fees and so on. He tried planting another giant a decade later, but this later scam didn't fool anyone.

Crystal skulls don't come from Central America

There's no question that the ancient Mesoamerican people, whose civilizations extended from Mexico down to Central America, were capable of brilliant scientific and artistic feats that still dazzle people today. Despite popular opinion, though, one thing those civilizations didn't do was make really cool, shiny crystal skulls, according to Chemical and Engineering News.

Crystal skulls reportedly carved by the ancient Aztec people have long appeared in major museums, some for over a century. Between inspiring a certain Indiana Jones movie and being the model for Crystal Head Vodka, the skulls are a genuine cultural icon. However, experts have had doubts for a long time. Not only were the skulls never found inside any documented archaeological digs, but the perfectly aligned design of the teeth is way different from how skulls are depicted in most traditional Aztec art. By the dawn of the 21st century, scientific techniques became advanced enough to prove that the skulls were all post-Spanish frauds, some circulated into museums by a shady French dealer named Eugène Boban. So admire the artistry of these things all you want, but don't believe the hype.

Vikings in Minnesota

If the fact that Minneapolis residents cheer on a team named the "Minnesota Vikings" wasn't a big enough clue, the North Star State has heavy Scandinavian roots. The only thing missing from Minnesota's identity is a great origin story, and the whole Leif Erikson thing doesn't cut it. Sure, Erikson was possibly the first European to sail to North America, but he was from Iceland rather than Norway, and he didn't go any further south than Canada. So, wouldn't it be cool if, perhaps, another Viking expedition had not only predated Columbus' arrival, but they'd also hiked for months through the snowy tundra, and taken up roots in the Midwest? What a great story!

Enter the 1898 discovery of the Kensington Runestone, first dug up in Solem, Minnesota, by a Swedish-American farmer and his son, according to Atlas Obscura. After dusting off the big sandstone object, the farmer found that it was covered in ancient Norse runes, so he brought it to nearby Kensington. Soon, everyone was buzzing that the big ol' rock was evidence of Vikings hitting Minnesota back in the 14th century. The murmur quieted once meddling scientists got their hands on the slab and pointed out that not only were the language inscriptions anachronistic, but the runestone itself couldn't be older than 500 years. Womp womp.

When an ancient mummy is actually a modern murder victim

The ancient Egyptians were known for making mummies, but they weren't the only society who preserved their corpses. One group that didn't practice mummification, though, was the Persians. So in 2000, history buffs recoiled in shock when someone tried to sell a "Persian Princess" mummy on the black market for millions of dollars. When the scheme got uncovered, according to Atlas Obscura, authorities were amazed to discover a sarcophagus containing a genuine mummy, with an inscription identifying it as Rhodugune, the daughter of King Xerxes of Persia. The Telegraph says the whole thing even sparked an ownership conflict between Iran, Pakistan, and the Taliban in Afghanistan.

Then the experts got involved, and things turned creepy. Careful research soon proved that the mummy wasn't an ancient princess, but instead, the dead body of a present-day woman who had been murdered around 1996, presumably by a blow to the neck. Sadly, the woman's identity was never discovered, and the case went cold. In 2005, the BBC reported that the woman's body was finally being laid to rest.

The Etruscan warriors who fooled the Met

For nearly 30 years, New York's famous Metropolitan Museum of Art featured a stunning exhibit of three Etruscan warrior sculptures, carved out of black terracotta, standing tall over everyone who dared approach them. According to Atlas Obscura, these beautiful pieces were first procured in the early 1900s, and their Greek appearance challenged the standard historical narrative regarding Roman artwork, since much of that culture was influenced by the Etruscans.

In layman's terms, the style of these statues didn't line up with the art history that scholars understood. That's because the statues were faker than the Easter Bunny, constructed in the 20th century by a wily trio of brothers named Riccardi, as well as their associate Alfredo Fioravanti. Despite clear signs that the Etruscan terracotta warriors were an anachronistic forgery, everyone was too excited about them to listen to the naysayers. That all changed in 1960, when a clever ceramic archaeologist named Joseph V. Noble put the Etruscan warriors to the test and showed the world how phony they were. By the next year, Fioravanti — the only surviving member of the original scam artist gang — confessed to the U.S. consulate in Rome that the whole thing was a big fat lie.

Be careful who you make fancy jewelry for

Scammers usually hire artists who are in on the deal, but not always. Just ask Israel Rouchomovsky, a Russian goldsmith who was commissioned by two strangers with big pockets in the late 1800s, according to io9, for a pretty simple design: make a very specific gold crown. Supposedly, the crown was a gift for their friend. No big deal, right? According to Life, he even cut the two guys a great price, giving them the crown for the equivalent of $1,000. Well, what Rouchomovsky didn't know is that the two men went on to sell the piece to the Louvre in Paris for 200,000 francs ($50,000 USD), by claiming that it had belonged to Saitaphernes, the third-century B.C. Scythian king. Just imagine if you'd knitted a blanket and then someone sold it as Abraham Lincoln's baby quilt, and you'll get a sense of how this goldsmith probably felt.

Guess what? The truth about the so-called "Tiara of Saitaphernes "came out. The Louvre got thoroughly roasted for it by local French papers, causing museum officials to blush redder than a fresh cherry. The Louvre quickly put their formerly prized item into the vault. Rouchomovsky did well, though — the notoriety made him a career, and the tiara has since traveled to other museums showing off his work.