Real People Who Died Searching For Mythical Places

Silver and gold! Everyone wishes for silver and gold! How do you measure its worth? By the willingness with which bold explorers will put their lives on the line in pursuit of it? That could be, because for centuries, tales — even implausible ones — of lost cities of gold, silver, and jewels have spurred ambitious, adventurous, and desperate people to risk life and limb to find outrageous sources of wealth and fortune.

It might be nice to think that if a person were seeking out an unknown land that their interests might be more scientific than mercenary, but almost without fail the places that inspire such reckless pursuit are ones reported to be full of — or even made of — silver and gold. The following are just a few examples of people who died in search of fabled lands of great wealth, or as a result of that search.

(And included just as a fun point of comparison is whether the truly legendary treasure hunter Scrooge McDuck managed to succeed where these lesser men failed.)

Lost in the Superstitions

The Lost Dutchman's Mine is one of the most famous lost treasures in the United States, allegedly tucked away somewhere in Arizona's Superstition Mountains, which supposedly houses a secret gold depository that variously belonged to an Apache Tribe, a Mexican family, a doctor from Illinois, and a German guy (no Dutchman), and is also allegedly a gateway to Hell. Nevertheless, so many people get that gold fever that as many as four or five treasure hunters die or disappear looking for it every year.

Probably the weirdest and ergo most famous of these is one Adolph Ruth, who, as explained by AZ Central, was a 66-year-old veterinarian who became convinced that one of many old maps he had collected led to the Dutchman's mine. Within a few days of beginning his expedition for gold, he disappeared. A bottle was found containing a note indicating that he had a) broken his leg and b) found the mine. The next year, his skull was found with a bullet hole in it, and a month later his body was found a mile away. Among his remains was a checkbook in which Ruth had scrawled "Veni, vidi, vici" ("I came, I saw, I conquered"). Super spooky stuff, Adolph! Why would you leave such cryptic notes and also throw your head a full mile away from your body? More like Adolph Rude.

(Did Scrooge McDuck succeed where Ruth failed? Yes! He found the Lost Dutchman's Mine in Uncle Scrooge #319.)

Seven Cities of Gold

The good news, as explained by History, is that Francisco Vazquez de Coronado was a significant early Spanish explorer (and also conquistador — that part is bad) whose 1540 expedition beginning at Mexico's western coast meant he was the first European to see the Grand Canyon and the mouth of the Colorado River. He was a provincial governor in New Spain (aka Mexico) by his late 20s. Cool job, Francis! Hopefully you don't ruin your historical reputation by fruitlessly seeking out a nonexistent series of gold-laden cities!

Oh, whoops, he did. Led on by reports from a missionary that the fabled Seven Cities of Cibola could be found in the region where New Mexico is today, de Coronado invested huge amounts of his and other people's money to find what actually turned out to be a Zuni Pueblo town with probably not that much gold in it at all. As they kept exploring, all they ever found was more native villages and more violent resistance from the inhabitants thereof. De Coronado returned to Mexico in shame and physically broken, where he was actually put on trial for being so bad a leader that it was against the law. He was cleared of the charge of being a criminally bad explorer, but weakened and scarred from his journeys, he died in Mexico in 1554.

(Did Uncle Scrooge find the Seven Cities of Gold? He sure did, in Uncle Scrooge #7, the story that very famously inspired the opening scene of Raiders of the Lost Ark.)

Catching ZZZs

Colonel Percy Fawcett was a super famous explorer! As History relates, over the course of some half-dozen expeditions into the wilds of the Amazon, Fawcett made maps of tons of uncharted territory in Brazil and Bolivia. His dangerous trips down South America way made him a celebrity and helped inspire Arthur Conan Doyle's The Lost World and some guy named Indiana Jones. The bad news is, like most of the dudes on this list, he's most famous for disappearing and/or dying on the job.

As time went on, Fawcett became obsessed with a pet theory that the Amazon was home to an ancient but advanced race that had built an expansive stone metropolis of "size and grandeur" in the thick of the jungle. He called his theoretical lost city "Z" and he devoted his life and resources to finding it. After two expeditions that had ended due to sickness, weather, and exhaustion, Fawcett began his third and final search for Z in 1925, taking along his son and best friend, but refusing the help of actual, literal Lawrence of Arabia (a real person) for some reason.

Setting out from New Jersey in January 1925, Fawcett (as we know now) completely overconfidently swore, "We shall return, and we shall bring back what we seek." *narrator voice* They didn't. All three disappeared without a trace, and worse, about 100 people have died in the years since looking for them.

(Uncle Scrooge never went to Z, but the story did inspire a pretty good 2016 film starring Charlie Hunnam as Percy Fawcett.)

Legend within a legend

If you've ever been to Florida, you've probably heard of Juan Ponce de Leon because tons of stuff there is named after him. And fair enough — the dude was the first European to go there after sailing north from Puerto Rico in 1513 in search of islands to explore and gold to line his pockets with. According to legend, however, he was looking for more than that. As the well-known story goes, the vain and ambitious Ponce de Leon was looking for the Fountain of Youth, which would secure his immortality, both figuratively and literally. One of the less charitable accounts of his life from 1535 says Poncey was specifically looking to cure some issues he was having with, you know, his business. He needed some vim and vigor in the downstairs parts, they said.

Except, as History explains, maybe not. Most of the accounts of Ponce de Leon's search for the Fountain of Youth didn't pop up until after the man's death, and there are no accounts of the Fountain anywhere in his surviving logs. Some historians maintain that King Ferdinand may have given him the mission, though, so not all hope that a man devoted his life to finding magic water is lost. (That part's probably not true either, actually. Sorry.) Either way, whether he was searching for a miraculous pool or just hoping to establish a new colony, dude took a fatal arrow to the thigh in 1521 in southwest Florida.

(Scrooge found the Fountain of Youth in Uncle Scrooge #32.)

The Road to El Dorado

Sir Walter Raleigh has the honor of being one of the few explorers on this list who are not most famous for dying or disappearing. He was, as History Is Now magazine explains, a famous writer, poet, and courtier of Queen Elizabeth I. Raleigh, North Carolina, among other places, is named for him. He (allegedly) invented that thing where a man puts his coat in the mud so a woman can walk over it. Unfortunately, he was also obsessed with gold and finding the legendary city of gold known as El Dorado.

Reading the writings of various Spanish explorers, including most notably a man named Juan Martinez, Raleigh became convinced that El Dorado was a) real, b) actually a city called Manoa, and c) in Guiana. So in 1595, he sailed to Guiana and began his first campaign to find El Dorado. He didn't find it. He didn't find it in 1616, either, on his second attempt. Worse still, on that trip Raleigh's friend Lawrence Keymis decided to break a peace treaty and attack a Spanish outpost in Guiana, which led to the death of Raleigh's son and the elder Raleigh's recall to England. King James was not super happy about Raleigh's main dude breaking a peace treaty, and Raleigh was executed for liking gold too much and the Spanish too little.

(Uncle Scrooge encountered the Gilded Man of El Dorado in Uncle Scrooge #311 after his nephew Donald met him in Dell Four Color #422.)

Other roads to El Dorado

Tons of people during the Age of Exploration found themselves on the search for El Dorado, the Lost City of Gold. Besides notable names like Sir Walter Raleigh and Gonzalo Jimenez de Quesada, as History's Shadow points out, many of these maybe-intrepid-maybe-foolish gold hunters were German. Led on by legends and misunderstandings of a king who washed himself in gold (which would be the real "El Dorado," or "the Gilded Man"), leaders of the German Welser colony in Venezuela would journey into the continent in search of riches untold.

After unsuccessful expeditions by Welser governors Ambrose Alfinger, Nikolaus Federmann, and Georg Hohermuth, in which the only gold found was plundered from native cities and provinces such as Cundinamarca, the last German governor of Welser was Philipp von Hutten, who wasn't deterred in the slightest by his predecessors' failures. Convinced that Cundinamarca couldn't possibly be the only gold-laden city in the Venezuelan interior, he spent five years from 1541 to 1546 looking for El Dorado. He didn't find gold, but he did find lead: Upon his return from his unsuccessful expedition, he, together with his traveling companion Bartholomew Welser Jr., was executed by a rogue member of the Spanish army who had taken over the Welser colony in his absence. Presumably von Hutten's ghost had the last laugh, however, watching generations of Spanish explorers also totally eat it while trying to find the mysterious and nonexistent city of gold.

The good silver

While many explorers died looking for gold, that wasn't the only precious metal that wealth-hungry Europeans were willing to die for in the Age of Discovery. If you can't find gold, silver is a pretty good, you know, silver medal. And why settle for some puny silver mine when you could have a literal mountain of the stuff? That's where legends of the Sierra de la Plata (the Mountain of Silver) come in.

In 1515 a Portuguese explorer named Aleixo Garcia, was shipwrecked among the Guarani people, one of only 18 survivors of an expedition to find a route to the Pacific Ocean. The Guarani told him the Incan legend of the Sierra de la Plata and the White King that ruled it and thus began an obsession. Garcia gathered an army of 2,000 Guarani and stormed into Inca territory hoping to find their silver mountain. All he found was himself and most of his allies murdered on the Paraguay River by a much larger Incan army.

Garcia's fate didn't faze subsequent explorers from trying to find the Silver Mountain, including Juan de Ayolas, who sailed a thousand miles up the Paraguay River, where he ran into one of Garcia's surviving companions, who only encouraged him in his search for gold and silver. Unfortunately for him, Ayolas and his entire expedition were killed by indigenous forces before he found his Sierra de la Plata. Nevertheless, belief that this territory held untold masses of silver gave it the name it still bears today: Argentina.

(No Scrooge story in the Sierra de la Plata yet. Maybe that's a tale for the next generation of Duck cartoonists.)

Lost in the Andes

Paititi is another legendary city of gold, an Inca legend nestled past the Andes deep in the jungle of Peru. Or Brazil. Bolivia, maybe. It was thought to be the last Inca stronghold after the Spanish conquest, where they actually hid most of their gold and silver, explaining why the Spanish found relatively little. It is identified with the Lost City of Z that Percy Fawcett disappeared looking for. But the thing that separates Paititi from, say, El Dorado or the Sierra de la Plata is that, as Forbes reports, archaeologists think they might have actually found it. Or at least the city that inspired the legends. Or at least, like, narrowed down where it might be, probably. Hmm, actually, this sounds pretty familiar. Be careful in that jungle, y'all.

Not every dangerous expedition for a lost city is one of distant memory. Take for example the 1971 French-American expedition led by Bob Nichols, Serge Debru, and Georges Puel, which saw their party head up the Rio Pantiacolla in search of the city of gold. When their month-long agreement with their guides expired, the three men saw themselves continuing on their journey alone, never to return. The following year, another explorer confirmed they had been killed by native people within the jungle. Modernity won't save you, it seems.

(Scrooge finds the lost wealth of the Incas in Uncle Scrooge #219.)

No passage

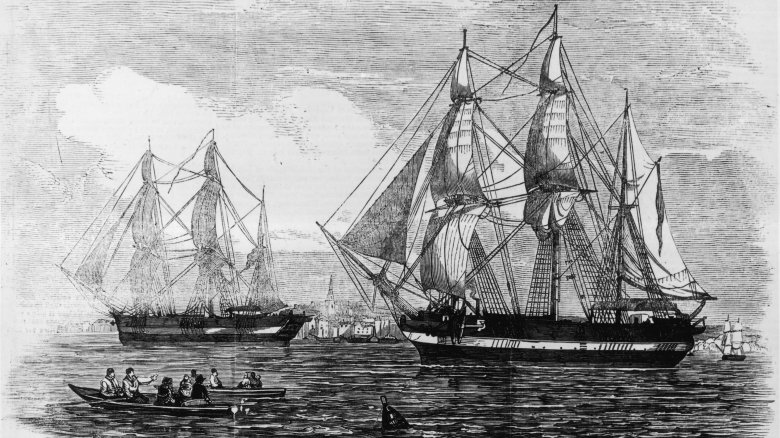

The Northwest Passage is a sea route through which a person sailing from the Atlantic Ocean could reach the Pacific Ocean via the Arctic Ocean, rather than, say, the Panama Canal. European explorers spent centuries looking for a way through the American continent by water. The thing that separates the Northwest Passage from the rest of the places on this list is that the Northwest Passage actually exists. And thanks to increasing Arctic temperatures and decreases in sea ice, it exists a lot more than it used to. Cool...?

But all the same, explorers spent a lot of time looking in vain for a navigable passage in places there just wasn't one, or else they just tried to brute force their way through an ungodly amount of ice. One of the most famous examples of a failed attempt to bash through the North Pole with a really big boat is the Franklin expedition of 1848, with their famous ships the HMS Terror and the HMS Erebus. The ships became hopelessly stuck in the sea ice and were abandoned, only for all 129 members of the expedition to die, the worst loss in the history of British polar exploration. Search crews attempted to find the ships for 11 years to no avail, but the Terror was found in 2016 at the bottom of an Arctic bay.

(Scrooge never sailed the Northwest Passage, but the novel The Terror and AMC's show based on it are a fictionalized version of the Franklin expedition.)

Lost but not a loser

Many of the men on this list, despite great deeds (in scope, if not in moral quality) and accomplishments, are nevertheless most remembered in modern times for their failures, disappearances, and deaths that came as a result of an obsession with a wealth, a myth, a legend that failed to materialize before them. But in the case of the Majorcan sailor Jaume Ferrer, literally all we know about him is that he hecked up to death looking for gold.

Thanks to a note by a mapmaker in an atlas from 1375, we know that Ferrer sailed from Majorca in 1346 to explore the West African coast with the intent of finding the fabled "River of Gold." A further note tells that Ferrer's expedition was lost and never heard from again. Despite this loss and failure to discover an African gold river, Ferrer is commemorated for his bold, pre-Columbian exploration past the previously assumed limits of European exploration in his hometown of Palma in Majorca by a statue, a street named after him, and a plaque in the town hall.

The "River of Gold," it turns out, referred to the Senegal River, which led to the heart of the Mali Empire, which did, in fact, have a lot of gold in it. It's just that the river itself wasn't, you know, literal gold. These early explorers needed to learn about the concept of metaphors, it seems.

(Scrooge did discover a golden river in Uncle Scrooge #22, but it wasn't in Africa.)