The Biggest SAG-AFTRA Boycotts And Strikes In History

The term "Golden Age of Hollywood" might conjure up all kinds of images of glitz and glamor, and while it was certainly that, it was a pretty dark time as far as the rights of the actual performers were concerned. All the beautiful people on the big screen were — off-screen — held to all kinds of standards and rules that look nothing short of barbaric today. They were often trapped in contracts that left them at the mercy of whatever studio they had signed with, wh ich usually included being told what movies they were going to be in, how they needed to change their appearance to conform to studio desires, and even what their name would be. It's not entirely surprising, then, that it wasn't long before actors had enough.

The Screen Actors Guild (SAG) was founded in 1933, and the idea was that it was going to protect actors from precisely the sorts of things that had happened two years prior: That was when Hollywood movie studios hired so-called "efficiency experts" to streamline operations and increase profits. One of the ways they did it? Cutting actors' salaries. And it was grueling work: Boris Karloff famously worked a 25-hour day on "Frankenstein."

Originally, AFTRA — the American Federation of Television and Radio Artists — was a separate entity, although the unions often worked hand-in-hand. The two merged in 2012 to form SAG-AFTRA, and with around 160,000 members as of 2023, they have some serious clout. And they've used it.

1952's TV strike

It took 19 years after the founding of the Screen Actors Guild for them to strike for the first time, and when they did, they made it quite clear that they meant what they said. On November 30, 1952, the 2,700-member guild officially went on strike to demand changes for something that might seem a little unlikely: television commercials. Although the announcement of the strike was given a relatively tiny number of column inches in The New York Times, the settlement of the strike and the SAG win got a bit more attention.

The strike lasted for 12 weeks and ended with some big changes to the way actors were paid for commercials — particularly those that were aired repeatedly. Previously, actors were paid a flat fee, despite commercials being reused or re-aired across the country. After the strike, pay scales were introduced to allow for repeated use and even for being broadcast in multiple cities. For example, actors received a base payment of $70 — which is about $800 in today's money — for commercials that aired in more than 20 cities. Actors were given an additional $50 — or about $566 — for each additional reuse, to a certain point: a buyout payment of $650 — or $7,365 today — would allow for unlimited use.

Different pay structures were used for smaller-distribution commercials and those that weren't shown during specific programs, but it was a big deal.

1960's SAG strike for residual payments

Ronald Reagan was, of course, famously an actor before jumping into politics. He was also the head of the Screen Actors Guild in the 1960s and spearheaded the movement to establish a system of residual payments for actors.

The emergence and new-found accessibility of a relatively new technology — television — was creating an important question for actors: Shoudn't they be getting payments when their work was aired over and over again, for studio profits? On the other side of the issue, the studios were asking why on earth actors thought they should get paid repeatedly for doing a job once. When talks went nowhere, then-SAG president Reagan organized a strike and on March 7, 1960, every SAG member did exactly what the studios were convinced they wouldn't do: They just didn't show up for work.

The results of the negotiations are still in effect today, and since the strike was settled five weeks after it began, more than $7 billion in actor residuals have been paid. Still, not everyone was happy with the deal at the time, which only required residuals to be set up for movies made from 1960 onwards. Bob Hope and Mickey Rooney were among the most vocal opponents of the deal that left decades of earlier films residual-free, but Reagan stuck by his plan, saying (via The Atlantic), "I think the benefits down through the years to performers will be greater than all the previous contracts we have negotiated, put together."

Threatening to take the 1967 Oscars off the air

By 1967, AFTRA represented about 18,000 people. When they decided to strike that year, something pretty cool — and ultimately trend-setting — happened: Even though the labor dispute only impacted a small percentage of those members, everyone made it quite clear that they were going to stand in solidarity with that small percentage.

On March 28, The New York Times reported that a strike was on after the disintegration of talks around the salaries of news readers on network-owned television stations. In addition to a base salary, they wanted a portion of the proceeds made from commercials that aired during their programs, and negotiations had come to a halt. So, everyone in AFTRA simply stopped working in support of the news readers — most famously, that included Walter Cronkite, who CBS briefly replaced with their news manager, Arnold Zenker. Other organizations — like the American Federation of Musicians and the Academy Awards — also joined.

AFTRA, it turns out, was holding some pretty big cards. As the days went on, the president of the Academy Awards stepped up and made it clear that if things weren't settled, they weren't going to air the Oscars — and that was an even bigger deal than it sounds. Not allowing the networks to air the festivities meant missing out on a whopping $700,000 licensing fee, so it was clear that everyone meant business. The strike lasted for 13 days and was settled in time to take the Oscars to television.

Commercials strike of 1978

Commercials might be those inconveniences that everyone skips today, but here's a bit of trivia: When the then-separate unions of SAG and AFTRA went on strike in 1978, commercials made up about half their collective revenue stream. It makes sense, then, that the 70,000 members would go on strike to protect that.

The issue was with a recently expired contract that representatives had failed to re-negotiate, and according to a letter partially quoted by The New York Times, "a strike is the only available means to resist employer demands which would set us back 25 years." More specifically, those demands included a clause that would allow companies filming commercials to require actors to do free-of-charge "alternate scenes" that they would only be paid for if those versions were selected to be aired. Union spokesman Ed Flynn described how they were blindsided when they found out new contracts were going to be negotiated with the goal of taking those payments away, telling the Times: "When they first put that on the table, we thought they were kidding."

The strike kicked off on December 19, and EUE Screen Gems production manager Dick Rose had started the whole thing with an odd flex: They had at least six months of unaired commercials in the bank, he claimed, implying that the actors were in for a very long wait if that's how they planned on playing things. It didn't take that long: The strike was settled on February 7, 1979.

1980 Actors' strike and Emmy boycott

Back at the dawn of the 1980s, VHS tapes and cable television created a way for people to watch movies at home. What, exactly, did that mean for actors and their revenue? That question is precisely what ended up leading to a joint SAG and AFTRA strike.

According to a report from The New York Times, talks stalled 47 days into the strike and after 15 days of negotiations: SAG and AFTRA wanted 6% but would compromise with 5.4%, while studios and producers were offering no more than 4.25%. The two sides ended up settling at 5.4%, but that's not entirely the end of the story. It's also worth noting that not everyone was happy — particularly Ed Asner. Asner became SAG president in 1981 and later explained to Back Stage that he had been campaigning not for a flat percentage but for a formula that would have increased actor pay as revenue increased. As it worked out, that didn't happen — and that 5.4% remained unchanged for decades. "That same baby has come back to haunt us ever since," he said.

There are a few footnotes, too. The strike turned that year's Emmys into a nightmare, with only a single actor breaking strike lines to accept his award. That was Powers Boothe, who said (via The Washington Post): "This is either the most courageous moment of my career or the stupidest." It also resulted in talks to merge SAG and AFTRA, although that wouldn't happen for another few decades.

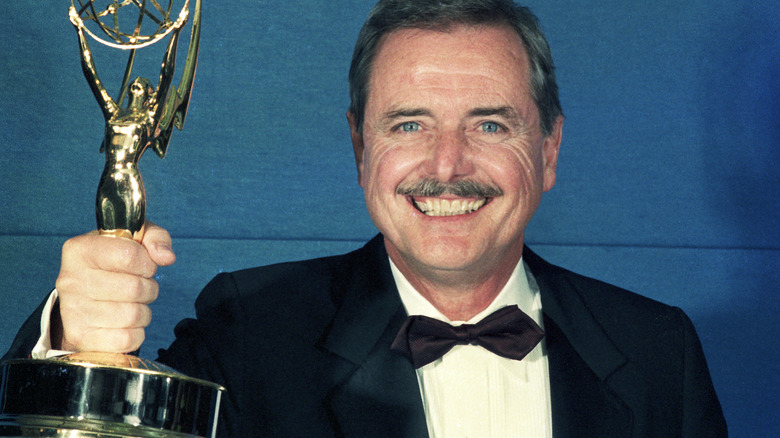

Advertising strike of 2000

When SAG and AFTRA went on a six-month strike in 2000, it was at a massive cost — literally. According to Reuters (via CNN), union members lost somewhere around $2 million per day during what was at the time the longest strike in Hollywood history. There was a lot at stake: It was time to renegotiate contracts, and the advertising agencies sitting across the table from SAG and AFTRA wanted to get rid of residuals for commercials. Also on the table? Exactly how actors were going to get paid for commercials that were broadcast on the internet.

The two sides ultimately met in the middle, but six months is a long time to go without a paycheck. Interestingly, some A-list actors — including Harrison Ford, Bruce Willis, and Nicolas Cage — pitched in with some massive donations that helped take the pressure off the actors and put it on the advertisers. Some of those advertisers were called out by name, with unions asking for a boycott of Procter & Gamble-owned properties like Tide.

That's not to say it was an easy strike, though. SAG's then-president William Daniels (also known as the voice of K.I.T.T. from "Knight Rider" and pictured in 1986) told Variety that, while the strike left him feeling burnt out, he wouldn't have changed a thing: "Nobody cared about commercial actors, and people who were not commercial actors did not have an understanding of their issues. I would do it again. It was worthwhile. I was very glad when it was finished."

Solidarity with the 2007-2008 WGA strike

Without writers, there would be no television or movies. Well, there would be no good television or movies, at least: Late night TV turned into Conan O'Brien seeing how long he could get his wedding ring to keep spinning on his desk, Steve Carell phoned it in on "The Office" — citing a very Michael Scott-like and completely unprintable illness — storylines across networks went off the deep end, and, well, let's just say the world ended up with "Quantum of Solace," and that was a bummer.

That 2007-2008 strike was organized by the Writers Guild of America, so what's that have to do with SAG-AFTRA? On the surface, nothing. When the WGA threatened to strike in 2023, for example, the official SAG-AFTRA position was (via Deadline) to cite a "no-strike" clause, which means that if another union went on strike, members of SAG-AFTRA were still expected to cross picket lines. Back in 2007 and 2008, though, scores of actors decided to ignore the heck out of that, and throw in with the writers.

In fact, they even organized their own picket lines, with dozens of actors — from Bill Paxton, January Jones, Minnie Driver, and Katherine Heigl to Julia Louis-Dreyfuss, Ray Romano, and Patrick Warburton — electing to protest outside of Universal Studios. Then, when the WGA announced they were going to picket the Golden Globes, SAG's then-president Alan Rosenberg made a formal announcement that no SAG actor would be attending to show solidarity.

Boycott of The Hobbit

Sometimes, SAG-AFTRA has called for boycotts on productions to stand in solidarity with international actors' unions, and that's what happened in 2010. When producers at the helm of Peter Jackson's "The Hobbit" refused the unionization efforts of the New Zealand branch of Australia's Media, Entertainment & Arts Alliance (MEAA), the then-separate entities of SAG and AFTRA both called on their members to boycott the film.

Jackson was, to put it mildly, not happy. He issued a statement saying, in part (via The Hollywood Reporter): "It sure feels like we are being attacked simply because we are a big fat juicy target — not for any wrong doing. It feels as if we have a large Aussie cousin kicking sand in our eyes ... or to put it another way, opportunists exploiting our film for their own political gain."

On the other side of the argument is the fact that the New Zealand branch of the MEAA had only been around for about four years at that point — and it had taken an overwhelming majority voting in a secret ballot to get that union to happen. At the time, no New Zealand-based productions had agreed to become unionized, with Jackson saying that was because the terms just weren't feasible. Jackson threatened to move the entire production, and it took involvement from New Zealand's government to settle the dispute. SAG ultimately lifted their boycott a week after it began.

2016-2017 video game voice actor strike

In 2016, SAG-AFTRA went on strike again to demand the same thing they'd demanded before: residual payments. This time, though, they were representing the voice actors who were working behind-the-scenes to breathe life into video game characters.

Jennifer Hale was one of those actors — gamers know her as the voice of Mass Effect's Commander Shepard. At the end of the 340-day strike, she explained the problems to CBC, and it was pretty awful stuff. For her, not getting residuals meant that for one of her early games, she was paid $1,600 for two work sessions. That sounds not-so-bad, but that game went on to make nearly $300 million, and she saw none of it. On top of that, they were also asking for better working conditions: "We have members who've lost their voices for months. Sometimes permanent damage — you know, bleeding from sessions, because the battle games, especially, are really demanding of someone's voice." Also on the list? The presence of stunt coordinators for motion capture sequence, and a rather surprising request for transparency: They wanted a guarantee that they would be told what game they were working on and who they were playing. Because a lot of the time? They have no idea.

At the end of the strike, voice actors were given an increase in pay but no residuals. Hale said that while it wasn't exactly what they'd hoped for, she was optimistic that it was a step in the right direction.

Bartle Bogle Hegarty strike

Advertising agency Bartle Bogle Hegarty (BBH) felt the full wrath of SAG-AFTRA in 2018, when the actors' guild called for a strike against only that agency. At the time, that meant BBH couldn't hire any of the 160,000 members of SAG-AFTRA, and that was a huge deal.

So, what happened? SAG-AFTRA's official statement on their relationship with BBH was pretty clear, and they condemned the agency for opting to shoot non-union commercials in what they said was an attempt to circumvent the requirements of their SAG-AFTRA contracts. In addition to the strike, they also went to the National Labor Relations Board with complaints of contract violations and stressed that the strike not only meant that no SAG-AFTRA member was to work for BBH, but they couldn't audition in preparation for an end to the strike, or renegotiate new contracts.

The strike lasted for a surprisingly long time, too, as BBH continued to contend that being held to SAG-AFTRA contracts just wasn't feasible. They claimed the whole thing was outdated, and it was 10 months before it was ruled that they legally needed to continue to abide by the terms of their agreement.

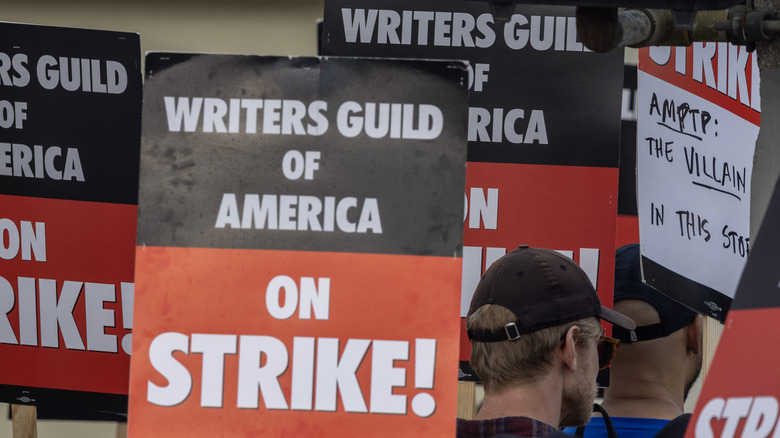

The emergence of AI and streaming services

SAG-AFTRA operates with what they call "Global Rule One," and it's pretty straightforward: Anyone who's a member can't work on a non-union production. One of the ways they have of encouraging productions to sign union contracts — and stick to them — is by essentially issuing small-scale boycotts and putting employers, companies, or even individuals (particularly producers) on "do-not-work" lists. That's exactly what it sounds like, and even though these lists might not make headlines the way that strikes do, they're still incredibly important.

SAG-AFTRA contracts officer Ray Rodriguez explained to The Hollywood Reporter, "Most productions that are subject to DNW orders resolve the underlying issues within a day or two, and the notices are thereafter rescinded." Some are a little more complicated.

At the time of this writing, one of the DNWs posted by SAG-AFTRA is a strict ban on "companies seeking to create, and license or use digital replicas of their voice or to train AI systems for use in audiobooks," and that's kind of a big deal. Emerging AI tech is, after all, a bigger concern than VHS tapes and home video were. WGA members began picketing in May, and in a move that hasn't happened since 1960, actors joined writers on strike in July 2023, not only due to concerns over AI but also to demand better contracts and pay, particularly with streaming services.