The Real Canterbury Tales: What A Medieval Pilgrimage Was Like

Quite a few modern readers are at least vaguely familiar with medieval pilgrimage through 14th-century poet Geoffrey Chaucer, whose work, "The Canterbury Tales," is an incomplete collection of stories told by a diverse group of pilgrims. These travelers are making their way together to England's holy site of Canterbury Cathedral. But Canterbury was hardly the beginning or the end of pilgrimages. Early Christians started trickling into holy places like Jerusalem on pilgrimages many centuries earlier. Going on a Christian pilgrimage became ever more popular, reaching its peak during the Middle Ages. By the 14th century, it's estimated that some 500,000 pilgrims made the trek to Spain's Santiago de Compostela in a single year.

Of course, plenty of other people have gone and still go on pilgrimages. Just look at the Hajj, the annual pilgrimage Muslims make to the holy city of Mecca, and which the faithful believe they must make at least once in their lives. Modern Christians might also feel called to make similar journeys, like the estimated 437,511 people who made the trek to Santiago de Compostela in 2022 (via Oficina de Acogida al Peregrino).

For anyone who's interested in learning more about the European Middle Ages, the medieval pilgrimage offers up a wealth of information. There were about as many ways one could go on pilgrimage as there were people in the medieval world — and perhaps just as many misconceptions about the trek. Here's what it was really like to head off on a medieval pilgrimage.

Pilgrimages could take the faithful near or far

For English pilgrims with the time and means to step away from their daily lives, it might be reasonable to make one's way to Canterbury. This site was made all the more famous in Geoffrey Chaucer's "The Canterbury Tales," though the sometimes holy, sometimes bawdy pilgrims in the text never make it to the titular cathedral, given that Chaucer never finished this work. In real life, Canterbury Cathedral was a seriously holy spot where, in December 1170, Archbishop Thomas Becket was murdered and soon thereafter became a venerated martyr whose relics were believed to hold miraculous healing powers.

More adventurous pilgrims could set out for the cathedral of Santiago de Compostela in Spain, walking the famous Camino de Santiago route by foot for a six-week journey (though some took it relatively easy by riding horses). If making their way to the pilgrimage site of Santiago de Compostela's richly decorated cathedral, reputed to be the burial spot of St. James, wasn't enough, there was always Rome. For medieval pilgrims, the ancient city was packed full of holy sites and divine relics that would have presented a plethora of sight-seeing spots and opportunities for divine intervention.

Yet, while making it to Canterbury or Rome was an achievement, the ultimate medieval pilgrimage took the faithful to the Holy Land. But, while places like Jerusalem were a big deal, getting there from far-flung places like England meant pilgrims had to go on long, difficult, and expensive journeys.

Some pilgrims had to make do with their imagination

Pilgrimages could be terribly expensive and often required weeks, months, or even years of travel. But if someone was literate and had access to the right manuscripts, they might still be able to go on a pilgrimage of the mind. Quite a few medieval writers used the metaphor of a pilgrimage to present religious messages and lead their readers to a closer relationship with God. Assuming they didn't mind a heavy reliance on allegory, readers could turn to works like "Piers Plowman," a 14th-century poem written in Middle English, allegedly by a rather mysterious man named William Langland. On the surface, the work describes a series of one person's dreams, but the visions unfold in a pilgrimage-like sequence that's meant to challenge and enlighten the reader.

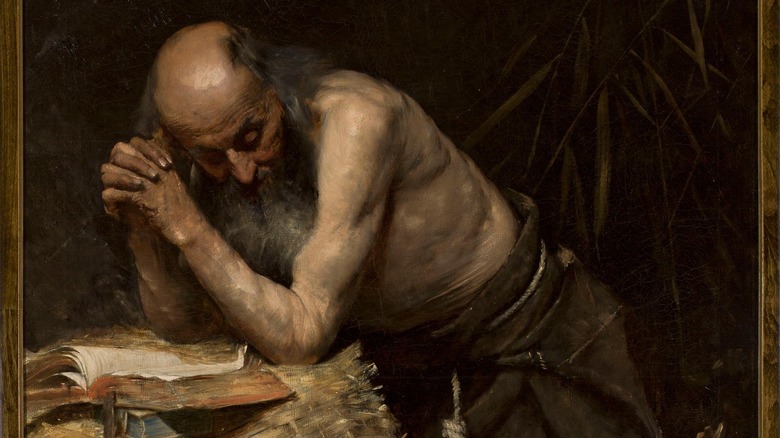

For some pilgrims, the idea of staying in one place was the whole point. Medieval England was peppered with Christians who withdrew from everyday society to go on an interior pilgrimage that would bring them closer to the divine. These could be cloistered nuns or monks, hermits, or even anchorites who chose to be walled up in a cell attached to a church for the rest of their lives. For them, the hubbub of getting up and hoofing it toward Jerusalem was only a distraction from the true goal. The real pilgrimage was all about a quiet life of prayer and study, sometimes marked by dramatic visions delivered straight from God.

Pilgrims were looking for relics

Many medieval pilgrims expected to enter an awe-inspiring church like Canterbury Cathedral, which was already centuries old by Chaucer's time, having been founded in A.D. 597. Other spots were also full of holy sites that, with or without a blinged-out church, would have attracted plenty of medieval travelers due to links to the Bible, like the alleged burial places of big-name saints Peter and Paul in Rome. But for many pilgrimage sites, the real draw was a saint's relic.

Relics, which typically are pieces of clothing from saints or bits of the saints' bodies, were believed by medieval folks to hold serious power. At Canterbury, pilgrims might be able to get a diluted sample of Thomas Becket's blood, said to have been spilled during his 12th-century assassination but conveniently available to the faithful on a continual basis centuries later. Other relics included a piece of Becket's skull, which was housed in a flashy reliquary by 1314, as well as part of the sword that was said to have been used in his murder. If they had done the proper round of fasting and praying first, pilgrims might even be offered the opportunity to kiss the skull fragment. Others could enter the Martyrdom Chapel, where Becket was killed, and kiss what they believed to be his footprints on the floor. Even the tomb that once held the archbishop's body, empty after his remains were moved in 1220, was still venerated by pilgrims.

Pilgrims might go for more worldly reasons

Obviously, engaging with one's faith was a major motivator for many medieval pilgrims, who wanted to visit holy sites and saints' relics in order to get that much closer to God and his representatives. Others might have been doing penance, perhaps for a major sin or just the general guilt accrued by being alive in the sometimes afterlife-obsessed Middle Ages and listening to their priest's fire and brimstone-focused sermons.

But these were hardly the only motivations for going on a pilgrimage. For those who could afford to take the journey, it could be a major sightseeing adventure that brought them to exotic locales and generated interesting stories they could tell for years to come. Others might go because it was a sort of family tradition, such as was the case for Birgitta of Sweden. Her father, grandfather, and so on back to her great-great-great grandfather, had reportedly made the trek from their homeland to Spain in order to visit Santiago de Compostela. So, when the time came, Birgitta and her husband, Ulf, dutifully made the trip themselves in the 14th century. Birgitta, who became well-known as a mystic and was eventually made a saint, turned out to be a bit of a pilgrimage fanatic. She even moved to Rome and started a religious community there, and eventually made a journey to the Holy Land shortly before her death in 1373.

Many might have been fulfilling a vow

Sometimes, a pilgrimage was the fulfillment of a very serious promise. A person who believed that they had received some benefit from God or a saint, like a hopeless illness that had been cured or safe passage through childbirth, might feel as if they were obliged to make the trek to show that they were properly thankful. Some even claimed that a saint had specifically appeared to them and, in exchange for help, demanded that the cured person visit their particular holy site. Other people who weren't under duress might still make a pilgrimage vow to express the depth of their religious devotion.

Keeping this sort of promise wasn't always easy, however. Besides the time and effort required to make it to one's destination, everyday duties could keep someone bound to their home. A wife and mother would have had a difficult time dropping her many obligations, for instance, while a peasant might have incurred the wrath of their lord if they simply dropped their farming implements and went off to Rome. This meant that some people were obliged to get permission before taking a pilgrimage vow or fulfilling it, like nuns who had to make their case before church fathers who suspected that they simply wanted to go on vacation. At other times, vows proved to be so difficult to fulfill that some once-hopeful pilgrims had to get their promises officially cleared so they could move on with their lives.

Some pilgrims sought a cure

In a society that lacked advanced health care, many seriously ill medieval Europeans might consider a pilgrimage as part of their treatment plan. Caretakers of shrines often took advantage of this motivation, telling stories of miraculous cures that would drive more pilgrims to their site. One 12th-century tale maintains that a girl who went to Canterbury for help saw St. James himself in a dream. The saint told her that if she went to Reading Abbey instead, where his hand was preserved, she would no longer suffer her disease.

Despite the actions of seemingly jealous saints, Canterbury remained a major pilgrimage site for anyone seeking help with sickness. It was especially renowned for anyone who had issues with bleeding, perhaps because Becket's assassination was particularly gory. Pilgrims might even be able to take home a small relic of their own to help others, like a cloth that had come in contact with a more major relic like Becket's tomb.

The most desperate might feel that their only hope was a pilgrimage. One 2017 report published in PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases describes the remains of one young man buried in medieval Winchester, England. Though he was interred with a distinct scallop shell given to many pilgrims, he was in the initial stages of leprosy and could have been suffering from visible damage. It could be that he made a distant pilgrimage hoping for a cure for what was then an otherwise incurable and socially isolating disease.

Many pilgrims donned special clothing

Even if a person walking or riding through a community wasn't very vocal about their pilgrimage, the purpose of their journey could have been immediately obvious after locals took a quick glance at their garb. One major reason so many pilgrims dressed in a similar way was simple practicality. In a time before planes, trains, or cars, the best most pilgrims could hope for when it came to travel was to go on horseback or in a wagon. Others simply walked — yes, even all the way to Jerusalem.

This sort of travel required sturdy, weather-resistant duds. The 14th-century poem "Piers Plowman" suggests a sensible bag and wide-brimmed hat, while a popular pilgrim song from the period recommends that travelers bring a couple of pairs of shoes (presumably, at least one would be worn through after much walking), a weather-resistant leather coat, and eating utensils like a bowl (via "Art and Architecture of Late Medieval Pilgrimage in Northern Europe and the British Isles"). Many other texts also suggest a good walking stick as a vital part of the pilgrim kit.

Eventually, the pilgrim look became a part of medieval iconography and signaled the wearer's holy intentions. Artworks from the period began to reference the look, showing pilgrims in long robes and wide-brimmed hats. Anyone associated with Saint James or his famous pilgrimage site of Santiago de Compostela (or, eventually, any pilgrimage) would have sported something with a scallop-shell motif, like a popular pilgrim's badge.

Pilgrimages could be dangerous

Even the most starry-eyed pilgrim had to confront the reality of their journey: it could be seriously scary. First, there was the physical toll of making a pilgrimage. Everyone was tired after a long day of journeying, whether a horse's saddle made them sore or their limbs were aching from miles upon miles of walking — with many more ahead. Most were also, frankly, pretty dirty. A few holy sites asked visitors to clean themselves before entering, sometimes offering special baths for that purpose.

The farther a pilgrim ventured, the more they might also feel they needed a guide to navigate unfamiliar and hostile terrain. They would also need to be wary of bandits who were looking to pick off unwary travelers, while also facing the dangers of the natural world, from weather to hungry animals. It's no wonder that the pilgrim's staff was so often recommended, as it could act both as a walking aid and a weapon to get a pilgrim out of a tight spot.

But bludgeoning unscrupulous locals with a big stick would only get a traveler so far. Unsavvy pilgrims might still fall victim to more canny hucksters selling fake relics or even the plague, the latter of which they hoped to fight off by wearing x-rated badges. The threat of being swindled was so keenly felt that some visitors to Jerusalem shed the traditional European pilgrim garb for local clothing in order to blend in and avoid making themselves targets.

Pilgrims had to face marketing

Much like popular vacation spots today have made tourism a key part of the local economy, pilgrimage sites could dramatically change the income of an otherwise obscure town (or at least boost visitor numbers in an already bustling city). While places like Canterbury didn't exactly have a medieval tourism bureau, a pilgrim-based economy nonetheless sprang up in this and many other holy sites. Though shrines like churches and chapels and their custodians were ultimately answerable to church officials, they were typically allowed to do what they wished with pilgrim donations, like assisting the poor or funding church building projects.

Shrine custodians who were getting anxious about their site's revenue didn't necessarily sit around and hope for a miracle. Some took the most holy relics and brought them on tour in an attempt to generate both awe and extra donations from local communities. Others kept careful records of all the miracles generated by their relics, which could act as a handy publicity tool to keep the pilgrims coming.

Of course, a shrine had to get a pilgrim-attracting relic in the first place. While some spots like Canterbury had relics that came ready-made with the site, others had to purchase holy relics (or what were believed to be holy relics) from a quasi-sanctioned black market that dealt in pieces of the saints.

Indulgences sullied the reputation of the medieval pilgrimage

Many pilgrims were willing to literally go the distance to humble themselves, come into contact with the holy, and generally improve the state of their souls. But, as the Middle Ages wore on, more people went on pilgrimage to take a bit of a spiritual shortcut. They were seeking indulgences, essentially a guarantee straight from the Church that a given action (or donation) would wipe one's sinful slate clean. That's certainly what Pope Boniface VIII said in A.D. 1300, when he promised that pilgrims who made it to Rome would be granted a complete pardon of their earthy sins, known as a plenary indulgence.

Attractive as the concept may have seemed to people who believed in the painful reality of hell and purgatory, indulgences were controversial. Many opponents of the practice claimed that this was cheating, pointing out that indulgences were more likely to be granted to people who made hefty donations to church projects. For some, the practice got to such an extreme that they simply didn't want to play along anymore. Martin Luther kickstarted the Protestant Reformation in 1517 partially because he claimed that the faithful couldn't simply buy their way out of hell.

Pilgrimage souvenirs were popular

Of course, someone couldn't be expected to travel on an arduous pilgrimage and not return with something to show the folks at home. In an era before branded plastic tchotchkes, airbrushed t-shirts, and other gift shop ephemera cluttered up our lives, souvenirs were still a thing. For medieval pilgrims, their own little relic of the journey often took the form of a badge purchased from a pilgrimage site. Most were made from malleable, easily-acquired metals like tin or lead and were sold at a low cost. They might have simply marked someone as a pilgrim to a given place, while fancier ones spoke to a given pilgrim's deeper pockets.

It's not entirely fair to take these little metal badges as mementos, however. They were also believed by many to carry some of the power of the original pilgrimage site, especially if they had been placed in direct contact with a holy relic. These badges may have also helped discourage pilgrims who might have otherwise snapped off a bit of the original shrine to take home. Other medieval badges, which included fantastical depictions of human genitals, were also possibly used as protective talismans against disease, as historian Winston E. Black told Atlas Obscura. Of course, it's always possible that medieval pilgrims — who were as human as we are, after all — just thought these naughty badges were funny.