The Time France's Entire Wine Industry Was Nearly Destroyed

Although wine is believed to have been first created in Asia, either in the Caucasus or in China, French wines are some of the most well-known wines in the world. Wine is incredibly important to the French economy and amounts to 15% of agricultural revenue, with the country exporting over $13 billion in wine every year (as of 2021).

But the industry wasn't always thriving. In the mid-1800s, the French wine industry was decimated by a near-microscopic foe known as grape phylloxera, a small insect that feeds on grape vines and their root systems, damaging and even killing them. Over the course of 25 years, almost half of all the vineyards in France were completely destroyed by this pest. And not only did this drive the price of wine up as supplies plummeted, but a huge chunk of the population was thrown into economic turmoil due to the fact that there were so many people who were involved with the wine industry.

But while the blight came from the United States, the remedy ended up involving the very grape plants that brought the blight to France in the first place.

French wine in the 1800s

During the French Revolution, the wine industry saw a number of changes that would culminate in its expansion during the 19th century. More planting was allowed and vineyards were expropriated from religious institutions, allowing many more individuals to enter the wine industry. The expropriated vineyards were auctioned off, but they were often puchased by the wealthy bourgeois like wine merchants, lawyers, or doctors. Some vineyards were also communally owned by farmers who tended vineyards in addition to farming cows and wheat, according to "The Wines of Chablis and the Grand Auxerrois," by Rosemary George.

By 1830, there were over 5 million acres of vineyards planted in France, and 32 million gallons of wine were being exported every year. At least 17,000 gallons of top-quality wine from France were exported every year to the British Empire. Other main wine markets included Sweden, Norway, Germany, Switzerland, and Mexico.

Wine was a big part of the French economy due to the fact that it was both produced and drank locally. There wasn't an industrial wine system like the one that would evolve in the late 19th century. And because the vineyards had been expropriated from the nobility, the price of wine fell so much that high-quality wines were as cheap as low-quality wines.

American plants

Attempts were also made to build a wine industry in the United States, but the original wine country wasn't in California. Surprisingly, it was in Ohio. Due to the horticultural efforts of Nicholas Longworth I, over 1,000 acres of vineyards were cultivated in the Ohio River Valley. And by 1859, Ohio was producing over a third of all the wine in the United States, totaling up to 570,000 gallons. In 1850, there were over 300 vineyards in Cincinnati alone. However, American vineyards often suffered from diseases like black rot and powdery mildew, and the harvests often didn't yield profits, an ominous foreshadowing of what France would soon experience.

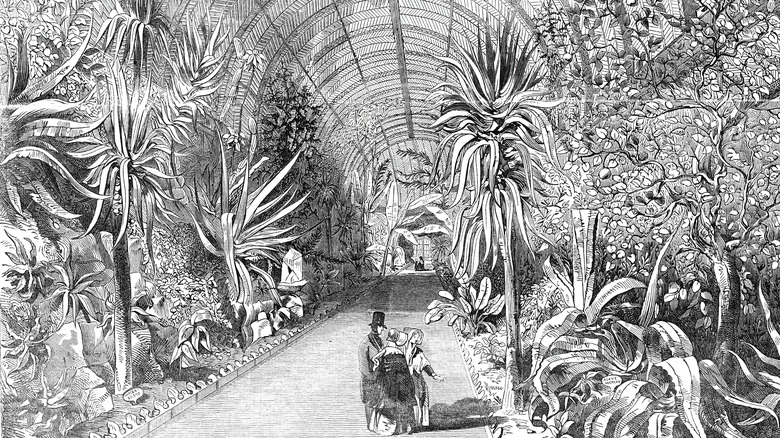

During the 19th century, thousands of plants were taken from North America to Europe, either for cultivation or for botanical interests. In 1865, over 450 tons of flora were brought to France from North America. Among them, American vines and vine roots were brought in substantially large quantities.

Plants were about aesthetics, and some of the imported plants were part of the Victorian craze of greenhouses and terrariums. But some of the imported vines were incorporated into vineyards. As a result, plants from the United States started bringing their native diseases, like powdery mildew, into Europe and contaminating European vines. And it wasn't a one-way movement of plant diseases. The import of European flora to North America caused the spread of the fungus Cryphonectria parasitica, also known as chestnut blight.

The first year of blight

But powdery mildew wouldn't be the only botanical disease unintentionally brought over to Europe from North America. In 1863, an insect known as phylloxera was first noticed in European vineyards when damaged leaves were discovered in both Hammersmith, West London, England, and Pujaut, France. But because the insect is practically invisible to the naked eye, the insect itself wouldn't be identified for several years.

Grape phylloxera, also known as phylloxera vastatrix, eats away at the healthy roots of the grapevine, causing the plant to leak sap irrevocably from the bite marks. Because phylloxera was native to North America, North American grape vines wouldn't completely succumb to an infestation and had evolved their own defenses. But European vines had no defenses whatsoever.

At the time, the wine industry was a huge part of many French people's lives. Up to 25% of the population had a job that was related to the wine industry. Some tried to move their vineyards elsewhere in France or to a nearby country, but they inevitably ended up taking the infecting cuttings with them and further perpetuating the blight.

Aphids or rot?

Initially, it was believed that the vineyards were suffering from a disease, rather than an infestation of insects. This was due to the fact that the phylloxera fed on healthy vines, and when growers and botanists would look at the unhealthy vines, they wouldn't find anything except roots that were already dead. Otherwise healthy-looking vines would simply start turning yellow, dropping their leaves, and dying.

Professor Jules-Émile Planchon was appointed by the French government as the head of a government commission to determine exactly the cause of the wine blight. And it wasn't until Planchon looked at the healthy-looking vines with a magnifier that he saw all the phylloxera. "An insect, a plant louse of yellowish color, tight on the wood, sucking the sap. One looked more attentively; it is not one, it is not ten, but hundreds, thousands of the lice that one perceived, all in various stages of development. They are everywhere," Planchon said, per "Wine: A Scientific Exploration," edited by Merton Sandler and Roger Pinder

But even then, the exact cause of the blight still remained a mystery because it wasn't clear if the phylloxera were a cause or a symptom. And phylloxera wouldn't be generally accepted as the cause of the wine blight until around 1874. This was largely due to the fact that French medicine at the time believed that diseases were due to an internal disequilibrium rather than an external cause.

[Featured image by Joachim Schmid via Wikimedia Commons | Cropped and scaled | CC BY-SA 3.0 Germany]

25 years of blight

Within five years of the first signs of phylloxera, most of southern France was plagued with the infestation and by 1890, all of France's vineyards were infected, known as the Great French Wine Blight. And between 1865 and 1890, phylloxera continued to spread across mainland Europe, consuming millions of grape vines. No one had any idea of what to do to save the vineyards, and one of the attempted remedies involved burying a toad under the vines while it was still alive. According to the Montreal Gazette, this was done with the hope that the toads would eat the phylloxera. Chickens were also used, but nothing seemed to work.

According to "About Wine" by J. Patrick Henderson and Dellie Rex, some of the vineyards in California from Sonoma to Napa Valley also ended up becoming infected due to phylloxera's mutations, despite having been originally immune to the insect's effects while it was localized in America. Meanwhile, phylloxera also spread East and would reach Bulgaria in 1883, affecting the Bulgarian wine industry until 1938, Yassen Borislavov writes in "Bulgarian Wine Book."

In total, it's estimated that phylloxera destroyed over six million acres of vineyards across Europe over the course of 25 years. In France alone, up to 40% of the vineyards were completely destroyed. During the blight, many smaller wine growers who didn't have any savings were forced to leave the wine industry and move away from the countryside.

An industry in shambles

As a result of the devastation caused by phylloxera, the French wine industry took a complete nosedive. Wages in the wine industry fell by 50% in some regions, while the property values of vineyards fell by 85%. Around Montpellier, the economy was described as being in "a general state of suffering" in 1878, according to "Popular Legitimism and the Monarchy in France," by Bernard Rulof. Because so many people were employed in the wine industry in one way or another, countless people lost their jobs, ranging from growers and retailers to construction workers.

In some places where the vineyards were destroyed by phylloxera, truffle orchards were cultivated instead. Absinth also became more popular during this time, as people sought to replace their daily wine with a cheaper and more available alcohol.

The economic crisis that some of the wine-producing regions suffered also had lasting effects on the local population. According to "The Oxford Handbook of Economics and Human Biology," edited by Dr. John Komlos and Dr. Inas Kelly, the adult height of men born during the wine blight in affected regions was relatively shorter than that of the average French man of the time, whose average height had been rising gradually during the 19th century. Essentially, due to the economic crisis caused by the French wine blight, the physical characteristics of people in the region were negatively affected for generations.

Moving to Algeria

Because of the phylloxera infestation, French vineyards became essentially unusable. And many French growers looked at Algeria as a place where they could settle and restart wine production. But because growers didn't know the cause of the blight until the 1880s, they ended up taking the infestation with their cuttings to Algeria, which ultimately prolonged the blight instead of solving it. Additionally, the blight inadvertently continued the colonization of Algeria and pushed the Indigenous people off their lands.

By the end of the 19th century, up to 50,000 French families settled in Algeria as they tried to escape the effects of the wine blight. As a result, the French colony of Algeria started producing an immense amount of wine, going from 25 million gallons in 1880 to over 100 million gallons annually by 1900. And by 1900, over 1.5 million acres in Algeria were being cultivated as vineyards by French people.

Wine became an incredibly important part of the French colony of Algeria among the colonists in the same way that it had been in France. Many colonists were involved in the wine industry, whether it was in growing grapes or making barrels for the wine. And according to Jadaliyya, Indigenous Algerians were also drawn into the wine industry, as colonists needed their help growing on unfamiliar land.

Grafting resistant rootstocks

In 1869, it was suggested that grafting American vines onto European vines would create a hybrid that could resist phylloxera. Grower Gaston Bazille suggested grafting the two plants together, but rather than grafting the vines together, they would graft the scion onto the American rootstock. Using the rootstocks of North American grape species Vitis berlandieri, Vitis riparia, and Vitis rupestris, the Vitis vinifera vineyards of Europe were hybridized and given a resistance against phylloxera through the American rootstocks.

But it wasn't a popular idea at first. Grafting was generally resisted as a solution due to the fear that the resulting wine would taste bad. And while some still claimed that the resulting graft irreparably changed the taste of the wine, others claim that the graft didn't affect the Vinifera taste. The idea was also resisted as it was thought that mixing North American plants with French plants endangered the latter's nascent national identity, which was tied to its historical and natural heritage, per "Wine and The Gift," edited by Peter J. Howland.

And despite figuring out that grafting rootstocks was a possible remedy, it still took a great deal of trial and error to create a sustainable defense. In the early 1870s, over 700,000 French vines died after being grafted during Jules-Émile Planchon's attempts.

Rewards for a cure

By 1874, it was accepted that phylloxera was the main cause of the wine blight, and was considered such a severe problem that the French government even advertised a reward for whoever could come up with a cure to get rid of phylloxera. The reward amounted to 300,000 Francs, roughly equivalent to over $5 million in 2023 (when based on gold).

Over the course of three years, the French government received over 600 suggestions on how to get rid of the insects. Suggestions ranged from various types of urine to carbon disulfide. One solution that worked, but was only viable if there was water nearby, involved flooding the area for several weeks to kill the insects.

But according to "Viticulture" by Stephen Skelton, despite the fact that grafting was discovered to be a remedy against blight, the French government refused to give Gaston Bazille the reward. They claimed that the reward was for getting rid of the insect, not necessarily keeping the plants alive.

The wine industry recovers

Once it was proven that grafting rootstocks was a remedy for phylloxera, the French government sought to revitalize the wine industry. Different forms of aid and subsidies were offered by the government. But the subsidies were rarely enough to actually help growers get back on their feet. And it would still take until the early 20th century for the French wine industry to fully recover.

In places like Languedoc, growers decided to use the subsidies towards planting grapes that were known to produce maximum yields. But according to "Cultivating Dissent" by Winnie Lem, grapes with high yields typically result in poor-quality wine, which resulted in alternating economic booms and crises in the region. This happened in several places in France in the 20th century, like Narbonne and Champagne, where the price of wine fell so much that it was poured into the streets, rather than be sold below cost.

The use of American rootstocks didn't come for free, either. In "Popular Legitimism and the Monarchy in France," Bernard Rulof writes that roughly 2,000 Francs per hectare had to be invested in growing phylloxera-resistant vines and, as a result, only wealthy winegrowers could afford to invest in the revitalization of the wine industry. But at the end of the day, the American rootstock became the best defense against phylloxera. And now, over 150 years later, the vast majority of French vineyards continue to grow on American rootstock.